Table of Contents |

A corporation always owes both legal and ethical duties to employees. These duties include providing a safe workplace, compensating workers fairly, and treating them with a sense of dignity and equality while respecting at least a minimum of their privacy. Managers should be ethical leaders who serve as role models and mentors for all employees. A manager’s job, perhaps the most important one, is to give people a reason to come back to work tomorrow.

Good managers model ethical behavior. If a corporation expects its employees to act ethically, that behavior must start at the top, where managers hold themselves to a high standard of conduct and can rightly say, “Follow my lead, and do as I do.” They walk their talk.

At a minimum, leaders model ethical behavior by not violating the law or company policy. One who says, “Get this deal done; I don’t care what it takes,” may be sending the message that unethical tactics and violating the spirit, if not the letter, of the law are acceptable. A manager who abuses company property by taking home office supplies or using the company’s computers for personal business but then disciplines any employee who does the same is not modeling ethical behavior. Likewise, a manager who consistently leaves early but expects all other employees to stay until the last minute is not demonstrating fairness. “Do as I say, not as I do” behaviors are a path to destruction for morale and are often associated with high turnover and low productivity.

Another responsibility business owes the workforce is transparency. This duty begins during the hiring process, when the company communicates to potential employees exactly what is expected of them. Once hired, employees should receive training on the company rules and expectations. Management should explain how an employee’s work contributes to the achievement of company-wide goals. In other words, a company owes it to its employees to keep them in the loop about significant matters that affect them and their job, whether good or bad, formal or informal. A more complete understanding of all relevant information usually results in a better working relationship.

That said, some occasions do arise when full transparency may not be warranted. If a company is in the midst of confidential negotiations to acquire, or be acquired by, another firm, this information must be kept secret until a deal has been completed (or abandoned). Regulatory statutes and criminal law may require this. Similarly, any internal personnel performance issues or employee criminal investigations should normally be kept confidential within the ranks of management.

Transparency can be especially important to workers in circumstances that involve major changes, such as layoffs, reductions in the workforce, plant closings, and other consequential events. These kinds of events typically have a psychological and financial impact on the entire workforce. However, some businesses fail to show leadership at the most crucial times. A leader who is honest and open with the employees should be able to say, “This is a very difficult decision, but one that I made, and I will stand behind and accept responsibility for it.” To workers, euphemisms such as “rightsizing” to describe layoffs and job loss only sound like corporate doublespeak designed to help managers justify, and thereby feel better (and minimize guilt), about their (or the company’s) decisions. An ethical company will give workers advance notice, a severance package, and assistance with the employment search, without being forced to do so by law. Proactive rather than reactive behavior is the ethical and just thing to do.

Historically, however, a significant number of companies and managers failed to demonstrate ethical leadership in layoffs, eventually leading Congress to take action. The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act of 1989 has now been in effect for over three decades, protecting workers and their families (as well as their communities) by mandating that employers provide sixty days’ advance notice of mass layoffs and plant closings. This law was enacted precisely because companies were not behaving ethically.

A report by the Cornell University Institute of Labor Relations indicated that, prior to passage of WARN, only 20% of displaced workers received written advance notice, and those who did received very short notice, usually a few days. Only 7% had two months’ notice of their impending displacement (Ehrenberg & Jacubson, 1993). Employers typically preferred to get as many days of work as possible from their workforces before a mass layoff or closing, figuring that workers might reduce productivity or look for other jobs sooner if the company were transparent and open about its situation. In other words, when companies put their own interests and needs ahead of the workforce, we can hardly call that ethical leadership.

Other management actions covered by WARN include outsourcing, automation, and artificial intelligence in the workplace. Arguably, a company has an ethical duty to notify workers who might be adversely affected even if the WARN law does not apply, demonstrating that the appropriate ethical standard for management often exceeds the minimum requirements of the law. Put another way, the law sometimes is often slow to keep up with ethical reflection on best management practices.

The primary federal law ensuring physical safety on the job is the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), which was passed in 1970. The goal of the law is to ensure that employers provide a workplace environment free of risk to employees’ safety and health, such as mechanical or electrical dangers, toxic chemicals, severe heat or cold, unsanitary conditions, and dangerous equipment. OSHA also refers to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which operates as a division of the Department of Labor and oversees enforcement of labor laws.

Employer obligations under OSHA include the duty to provide a safe workplace free of serious hazards, to identify and eliminate health and safety hazards, to inform employees of hazards present on the job, to institute training protocols sufficient to address them, to extend to employees protective gear and appropriate safeguards at no cost to them, and to publicly post and maintain records of worker injuries and OSHA citations.

OSHA and related regulations give employees several important rights, including the right to make a confidential complaint with OSHA that might result in an inspection of the workplace, to obtain information about the hazards of the workplace and ways to avoid harm, to obtain and review documentation of work-related illnesses and injuries at the job site, to obtain copies of tests done to measure workplace hazards, and protection against any employer sanctions as a consequence of complaining to OSHA about workplace conditions or hazards. A worker who believes his or her OSHA rights are being violated can make an anonymous report. OSHA will then establish whether there are reasonable grounds for believing a violation exists. If so, OSHA will conduct an inspection of the workplace and report any findings to the employer and employee, or their representatives, including any steps needed to correct safety and health issues.

OSHA has the authority to levy significant fines against companies that commit serious violations. The largest imposed to date were against BP, the oil company responsible for the largest oil spill in history in April 2010. OSHA took into account that eleven workers died and several more were injured on BP’s rig, Deepwater Horizon, as a result of the initial explosion and fire. Consequently, rig worker safety was upgraded by statute. The second largest fine was also against BP, for a refinery explosion in Texas City, Texas, in 2005. Of course, these are high-profile cases in high-risk industries, but OSHA provides protection to all workers in all industries. For example, movie and television productions may not generally be considered high-risk settings, but on-set injuries and deaths have led to OSHA citations for the television show Tales of the Walking Dead, and the movies Midnight Rider and Rust. (In Tales of the Walking Dead, a performer suffered a head injury after doing a stunt. A camera person for Midnight Rider was hit by a train while shooting scenes near tracks. In the movie Rust, a gun was loaded with live ammunition by accident and actor Alec Baldwin shot a crew member. In all of these cases, negligence on the part of the production team was to blame.)

These fines demonstrate that the agency is serious about trying to protect the environment and workers. However, for some, the question remains whether it is more profitable for a business to gamble on cutting corners on safety and pay the fine if caught than to spend the money ahead of time to make workplaces completely safe. For this reason, there are additional fines levied for willful violations of OSHA regulations versus accidental oversights. Moreover, OSHA fines do not really tell the whole story of the penalties for workplace safety issues. There can also be significant civil liability exposure and public relations damage, as well as worker compensation payments and adverse media coverage, making an unsafe workplace a very expensive risk on multiple levels.

In addition to assuring workers of a safe work environment, employers have an ethical and legal duty to provide a workplace free of harassment of all types. This includes harassment based on sexual and gender identity, race, religion, national origin, age, disability, and other categories. While it generally applies to the work environment, it can be applied to activity off work; for example, a series of unwanted texts harassing a colleague after hours or bullying a coworker on social media would still be considered workplace harassment.

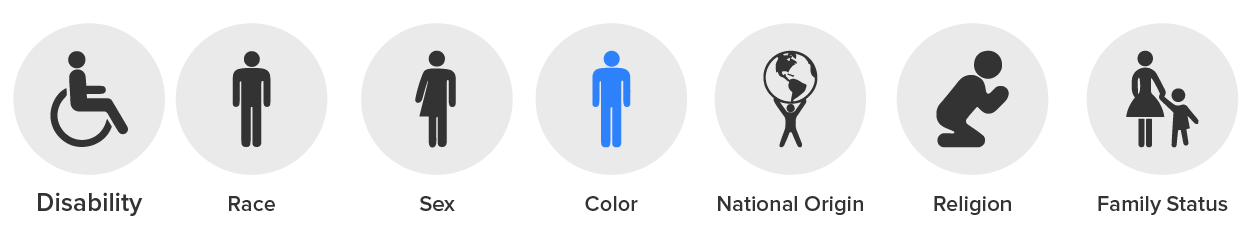

Legally, these obligations are overseen by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which strives to eliminate harassment and discrimination in the workplace against protected classes. Protected classes are specific groups that have been identified as requiring legal protection due to a history of discrimination. They include:

The two categories with the most complaints are gender and racial discrimination; together, these categories made up about two-thirds of all cases filed with the EEOC. More than thirty thousand complaints of sexual, gender, racial, or creedal harassment are filed each year, illustrating the frequency of the problem.

The EEOC enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (CRA) of 1964, which prohibits workplace discrimination including sexual harassment. According to EEOC guidelines, it is unlawful to harass a person, either through explicit offers in exchange for sexual favors (known as quid pro quo) or through actions at a broader, more systemic level that create a “hostile working environment.” Sexual harassment includes unwelcome touching, requests for sexual favors, any other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature, offensive remarks based on a person’s sex, and off-color jokes. The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor (which creates company liability the first time it happens) or a peer coworker (which usually creates liability after the second time it happens, assuming the company had notice of the first occurrence). It can even be someone who is not an employee, such as a client or customer, and the law applies to men, women, and transgender people. Thus, the victim and the harasser both can be a woman, man, or transgender person, and offenses include both opposite-sex, transgender, and same-sex harassment.

Although the law does not prohibit mild teasing, offhand comments, or isolated incidents that are not serious, harassment does become illegal when, according to the law, it is so frequent “that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment or when it is so severe that it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim being fired or demoted).” It can happen between anyone, of any gender orientation. It is management’s responsibility to prevent harassment through education, training, and enforcement of a policy against it, and failure to do so will result in legal liability for the company.

In 2017 and 2018, a renewed focus on sexual harassment in the workplace and other inappropriate sexual behaviors brought a stream of accusations against high-profile men in politics, entertainment, sports, and business. They included entertainment industry mogul Harvey Weinstein; Pixar’s John Lasseter; on-air personalities Matt Lauer and Charlie Rose; politicians such as Roy Moore, John Conyers, and Al Franken; and Uber’s Kalanick, to name just a few. The CEOs of Uber and American Apparel were let go after systematic sexual harassment was revealed. While most high-profile cases involve men harassing women, remember that men can harass other men, women can harass men or other women, and so on. The law protects everyone and applies to everyone.

The workplace harassment problem has continued for many decades despite the EEOC’s enforcement efforts. It can happen to anyone. It remains to be seen whether new public scrutiny will prompt a permanent change in the workplace.

| Summary of Laws | ||

|---|---|---|

| Common name | Short for… | Purpose |

| WARN (acronym) | Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification | Requires ample notice of massive layoffs or factory closures. |

| OSHA (acronym) | Occupational Safety and Health Act (also Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which enforces the act) | Enforces laws that set standards for physical safety of employees, particularly in high-risk settings. |

| EEOC (initialism) | Equal Employment Opportunity Commission | Enforces a number of laws related to discrimination, especially racial and sex discrimination. |

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "BUSINESS ETHICS". ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/BUSINESS-ETHICS/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Ehrenberg. R.G. & Jacubson, G.H. (1993). Why WARN? The Impact of Recent Plant-Closing and Layoff Prenotification Legislation in the United States. In C. Beuchtemann (Ed.) Employment Security and Labor Market Behavior (200-214). Cornell University Press. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9914.1993.tb00203.x