Table of Contents |

Broadway producer and composer George M. Cohan wrote one of the most famous songs of the World War I era, “Over There,” in April of 1917, after President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The song’s chorus is provided below:

Broadway producer and composer George M. Cohan wrote one of the most famous songs of the World War I era, “Over There,” in April of 1917, after President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The song’s chorus is provided below:

Chorus from “Over There”

“Over there over there

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming,

The drums rum-tumming ev’rywhere

So prepare say a pray’r

Send the word, send the word to beware

We’ll be over, we’re coming over,

And we won’t come back till it’s over over there!”

Additional Resource

Visit the Library of Congress to listen to the audio of “Over There.”

While the United States declared war on Germany and composers like Cohan expressed optimism about the contributions that American boys would make overseas, the Allied forces in Europe were close to exhaustion. Great Britain and France had heavily indebted themselves by purchasing American military supplies. They asked the United States to send reinforcements immediately to boost Allied spirits and strengthen their lines against German attacks. Wilson agreed and sent 200,000 soldiers to France in June 1917. These men were deployed in “quiet zones,” where they trained and prepared for combat.

The Allies’ prospects grew even bleaker in March 1918 when Germany won the war on the Eastern Front. A year earlier, the Russian Revolution toppled the regime of Tsar Nicholas II and began a civil war in which communist revolutionaries known as Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, emerged victorious. Weakened by war and internal strife and eager to build a new Soviet Union, Russian delegates agreed to a generous peace treaty with Germany to end the war in the East.

Emboldened by its victory over Russia, Germany launched an offensive on the Western Front in the spring of 1918.

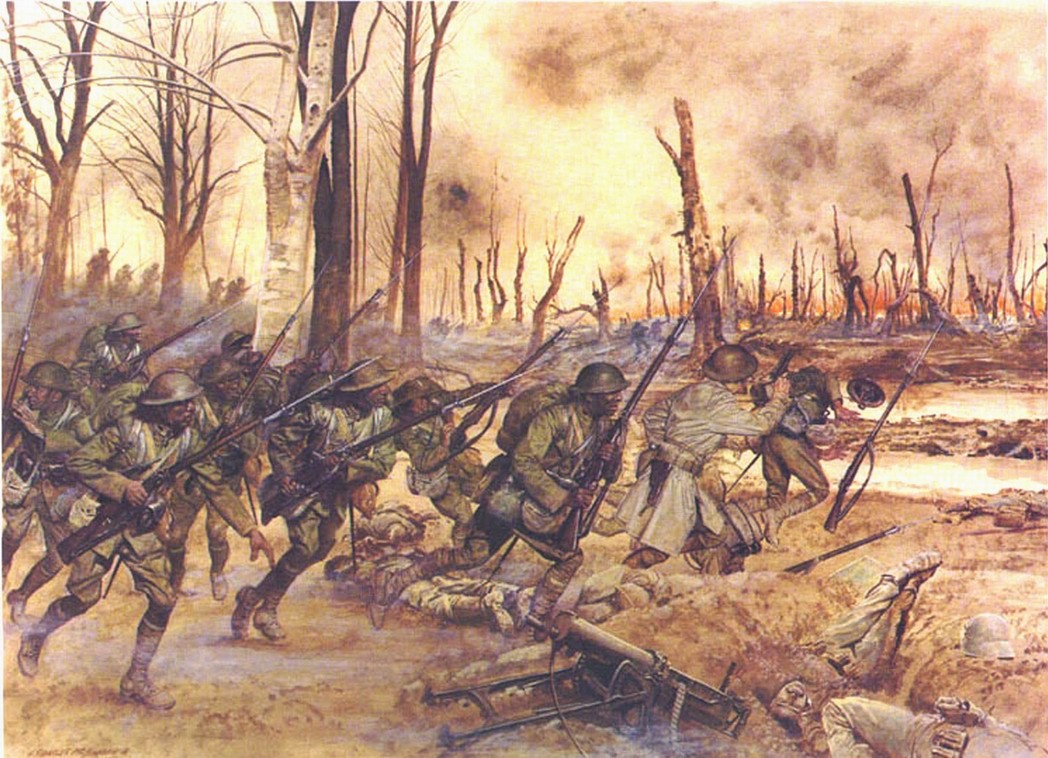

As German forces advanced toward Paris, France and Great Britain asked President Woodrow Wilson to end the training of U.S. troops and to send them to the front immediately. Wilson complied and ordered the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, General John Pershing, to relieve the exhausted Allies. By May 1918, American soldiers were fully engaged in the war. They played a key role in turning back the German offensive.

In November—after almost 40 days of intense fighting—the Allied forces broke through the German lines. Facing civil unrest from the German people and a lack of support from his military commanders, the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, abdicated his throne on November 9, 1918. Two days later, on November 11, 1918, Germany and the Allied Powers declared an armistice to end fighting on the Western Front.

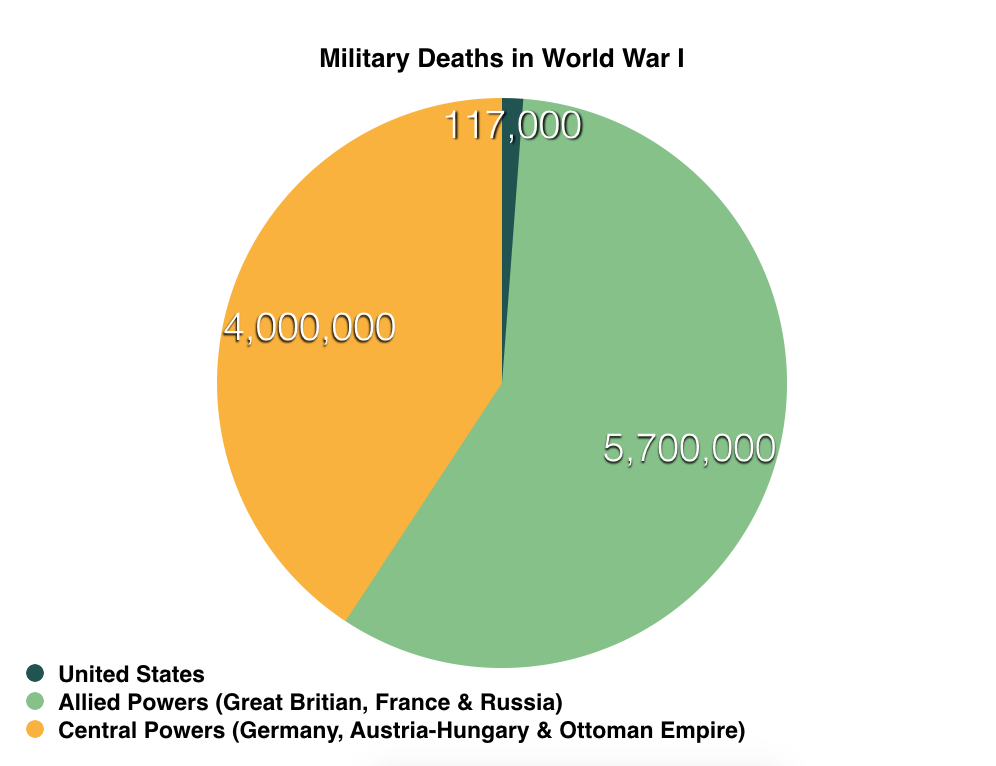

By the time the armistice was declared, 117,000 American soldiers had been killed and 206,000 wounded. These statistics paled in comparison to the costs experienced by European nations, as shown in the chart below:

As a result of the grim price that Great Britain and France had paid while fighting on the Western Front, the leaders of both countries were determined to take revenge and gain territory at the expense of Germany. They were determined that Germany be rendered incapable of starting another war.

Their goals put them at odds with President Wilson, who wanted to use American influence to achieve a “cooperative peace” that did more than satisfy the immediate desires of the victors.

President Wilson saw American participation in the First World War as justification for his vision of a new foreign policy framework, a “new world order,” for the entire globe.

Remember that Wilson outlined his vision for “peace without victory” in a speech to Congress in January 1917. During this speech, he made a series of proposals to achieve this vision. In January 1918, these proposals became known as the Fourteen Points.

Historians have simplified the Fourteen Points into a core list of agreements and goals that, taken together, Wilson called a “program of the world’s peace”:

Wilson’s Fourteen Points

- No secret international treaties and alliances

- Free navigation of the seas in times of peace and war

- Free trade between nations

- General reduction of armaments

- An impartial adjustment of all colonial claims by European powers

- Restoration of all Russian territory invaded by Germany

- Evacuation of German forces from Belgium

- Restoration of all French territory invaded by Germany

- Readjustment of Italy’s borders along the lines of nationality

- Independence for various national groups within Austria-Hungary

- Independence for Balkan nations along the lines of nationality

- Autonomy for ethnic groups under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and freedom to navigate the Dardanelles strait between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea

- Independence for Poland

- Establishment of a League of Nations

In summary, the Fourteen Points called for openness in diplomacy and trade: an end to secret treaties and negotiations, free trade, and freedom of the seas. In his speech, Wilson declared that “every people should be left free to determine its own polity, its own way of development, unhindered, unthreatened, unafraid,” a principle known today as self-determination. To realize this principle, Wilson advocated the creation of new Eastern European nations based on the region’s ethnic diversity and called upon all dominant nations to begin decolonization. The Fourteen Points also called for arms reduction across the globe.

Most importantly, Wilson proposed the establishment of an international organization—the League of Nations—to advance the new world order, to ensure that “no such catastrophe” such as World War I “shall ever overwhelm us again,” and to preserve world peace through discussion and debate, rather than intimidation or war.

After the Armistice was signed, Wilson announced that he would attend the peace conference in Paris, instead of sending a diplomatic representative. The other participating nations followed suit. The Paris Peace Conference, which began in December 1918, was the largest meeting of world leaders in history.

Germany was excluded from the peace conference. The leaders of the Allied Powers, especially Great Britain and France, viewed Wilson’s goal of “peace without victory” and the Fourteen Points with skepticism. In addition to territory, Great Britain and France sought substantial monetary reparations from Germany for their wartime losses.

The Treaty of Versailles that officially ended World War I bore little resemblance to Wilson’s Fourteen Points. France and Britain divided most of Germany’s colonial holdings in Africa and Asia between them. The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire led to the formation of new nations in the Middle East (e.g., Iraq and Palestine) under the quasi-colonial rule of France or Great Britain. France also gained territory along its border with Germany.

Most notably (and in stark contrast to Wilson’s vision), the treaty included a “war guilt clause” in which Germany was required to take responsibility for starting the First World War and to pay reparations in excess of $33 billion to the Allied Powers.

President Wilson conceded most of the 14 points listed above to secure the creation of the League of Nations, the crown jewel of the Fourteen Points. In a covenant agreed to at the conference, the Allies agreed to form a league that would promote the peaceful resolution of international disputes through arbitration or, when necessary, by imposing economic sanctions.

The most controversial aspect of the League of Nations agreement was a collective security measure known as Article X.

Pleased with his efforts on behalf of the League of Nations, President Wilson, and other world leaders, signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. He then hurried back to Washington, DC, to secure ratification of the treaty from the Senate.

Although the other nations agreed to the final terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson’s greatest battle for the League of Nations awaited his return to the United States. All treaties require two-thirds approval by the U.S. Senate for ratification. Wilson knew that this would be difficult to achieve, even with the support of his fellow Democrats in Congress.

The ratification debate focused on the role the United States should play in the postwar world, particularly in the League of Nations.

EXAMPLE

Before President Wilson returned to Washington, DC, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (pictured right), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that oversaw ratification proceedings, issued a list of 14 reservations regarding the Treaty of Versailles. Most of them involved the creation of a League of Nations.A handful of Republican senators, known as Irreconcilables, opposed ratification on all grounds. Others, like Lodge, were known as Reservationists. They indicated that they would support the treaty—with certain amendments.

Much of the debate over the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations centered on Article X, as illustrated by the table below:

| Reservationists | Irreconcilables | |

|---|---|---|

| Stance on the Treaty of Versailles | Would support the treaty if the president accepted certain amendments | Opposed ratifying the Treaty of Versailles on all grounds |

| Stance on Article X | Feared the League of Nations could use Article X to prevent the United States from using its military power to secure and protect its international interests, including those in Latin America and in the Pacific | Argued that Article X infringed on American sovereignty and moved the power to declare war from Congress to the League of Nations |

President Wilson refused to compromise with the Senate. He embarked on a public speaking tour to generate public support for the Treaty of Versailles. The tour’s grueling pace proved to be too much for him, however. He fainted after delivering a speech in Colorado on September 25, 1919. He immediately returned to Washington and, shortly thereafter, suffered a debilitating stroke.

Frustrated that his dream of a “new world order” was slipping away—the frustration compounded by his inability to speak coherently—Wilson urged Senate Democrats to reject any compromise on the treaty. Nevertheless, on November 19, 1919, the Senate voted to reject the original Treaty of Versailles. An amended version was proposed, one that significantly limited America’s obligations to the League of Nations. It also fell short of the two-thirds majority required for ratification. As a result, the United States did not sign the Treaty of Versailles.

Failure to ratify the Treaty of Versailles meant that the United States did not join the League of Nations. Wilson remained angry at the Senate for refusing to ratify, but other factors contributed to the country’s failure to join the League of Nations. Wilson and Henry Cabot Lodge disliked each other. It is likely that their personal feelings interfered with treaty negotiations. Partisanship was also to blame. Divisions along party lines influenced the ratification debate. Democrats were criticized for standing with Wilson in his support of the Treaty of Versailles instead of working with Republicans to amend it so that a majority could agree to ratify it.

Finally, much of the blame lies with President Wilson. In pursuing his vision of a “new world order,” one in which the United States would play a key role in organizing international agreements and resolving international disputes, he ignored a number of legitimate concerns. His insistence on “peace without victory,” though admirable, led him to dismiss French and British demands for monetary reparations from Germany in the aftermath of the most devastating war the world had ever seen. Likewise, Wilson’s vision of American participation in the League of Nations ignored American foreign policy traditions regarding sovereignty and unilateralism.

The United States did not retreat into isolationism following the First World War, but it was clear that the nation would continue to assert its interests and interact with the world on its own terms.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

“Over There” information, LOC bit.ly/2oz5HFV

“Over There” lyrics, LOC bit.ly/2nMpXXg

A World League of Peace speech, Miller Center, bit.ly/2nw5F21

“Fourteen Points,” Miller Center bit.ly/2nhhbg6