Table of Contents |

Woodrow Wilson was sworn in as president in March 1913, after a hotly contested election campaign with his two presidential predecessors, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. Wilson shared the commonly held beliefs that had formed the foundation of their foreign policy:

Unlike his predecessors, however, Wilson added an idealistic component to American foreign policy. He assumed that democracy was the best form of government to promote peace and stability in the world, and he believed that American values, especially individualism and free enterprise, were universally good. Although Wilson, like Taft and Roosevelt, believed that foreign policy should be based on commercial interests and geopolitics, he hoped to use it to spread democracy, self-determination, and human rights throughout the world.

Wilson reassured Latin America by promising not to rely on the Roosevelt Corollary.

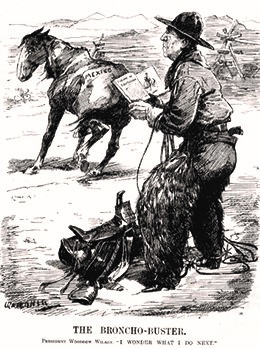

Despite his reassurances, Wilson’s administration intervened in Latin American affairs more than either of its predecessors. His most notable intervention occurred in Mexico, where a revolution began in 1911. Wilson refused to recognize the new Mexican government under General Victoriano Huerta (who assassinated the previous Mexican president). Instead, he supported Venustiano Carranza, who opposed Huerta’s military administration. Wilson saw the crisis as an opportunity to influence Mexico’s internal politics. He demanded that Mexico hold democratic elections, but both Huerta and Carranza balked at the possibility of the United States sponsoring elections in their country.

Fighting between the United States and Mexico began in Veracruz on April 22, 1914, after the United States attempted to block the delivery of weapons to Huerta’s forces. The clash resulted in approximately 150 deaths, 19 of them American. The United States occupied Veracruz until November.

Fighting between the United States and Mexico began in Veracruz on April 22, 1914, after the United States attempted to block the delivery of weapons to Huerta’s forces. The clash resulted in approximately 150 deaths, 19 of them American. The United States occupied Veracruz until November.

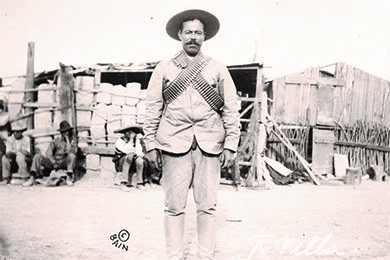

By the spring of 1916, the Mexican Revolution threatened to cross the American border. Frustrated by Wilson’s support of Carranza, Pancho Villa (pictured left), the leader of a rival revolutionary faction, confiscated property in northern Mexico that was owned by Americans. On March 9, 1916, he led his forces across the border to attack and burn the town of Columbus, New Mexico. Over 100 people died, including 17 Americans.

Wilson responded to Villa’s attack by sending approximately 10,000 troops under General John Pershing to Mexico to arrest him. This campaign, dubbed the “Punitive Expedition,” failed to capture Villa, and, after a brief engagement with Carranza’s forces brought both nations to the brink of war, Wilson reluctantly ordered a withdrawal in the spring of 1917.

Wilson sympathized with the goals of the Mexican Revolution. His dealings with Huerta and Carranza reveal his belief that he could guide the Mexican Revolution to a democratic outcome—similar to the outcome of the Revolutionary War. The incidents at Veracruz and along the border, however, revealed that the United States was willing to intervene in another country’s affairs when its commercial or geopolitical interests were threatened.

By avoiding a prolonged occupation and conflict in Mexico, the United States was able to prepare to intervene in another conflict: the First World War.

The murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a Serbian nationalist on June 29, 1914, sparked conflict between several European mutual-defense alliances:

The First World War, known at the time as the Great War, was unlike any military conflict that preceded it. New technologies transformed warfare, taking it from open battlefields into the trenches. Artillery, tanks, airplanes, machine guns, barbed wire, and poison gas strengthened the defensive positions of both sides and turned each offensive into a sacrifice of thousands of lives in return for minimal territorial gains.

EXAMPLE

During the Battle of the Somme (July–November 1916), Great Britain suffered 400,000 casualties. By the end of the battle, British forces had achieved no significant change in their position.

By the end of the war, which lasted from 1914 until 1918, the military death toll was 10 million, along with 1 million civilian deaths attributed to military action. Another 6 million civilians died during the war from famine, disease, and other causes.

President Wilson attempted to maintain American neutrality as the war in Europe began. Few Americans wanted the United States to enter the war, and Wilson did not want to risk losing the reelection in 1916 by ordering an unpopular military intervention. He also considered the war a European affair and wanted to maintain working—that is, commercial—relations with European nations.

Wilson first indicated that the United States would remain neutral on August 20, 1914:

President Woodrow Wilson, August 1914

“The effect of the war upon the United States will depend upon what American citizens say and do. Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned . . . .

I venture, therefore, my fellow countrymen, to speak a solemn word of warning to you against that deepest, most subtle, most essential breach of neutrality which may spring out of partisanship, out of passionately taking sides. The United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name . . . . We must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another.”

One of the terrifying new developments in military technology directly challenged American neutrality: the German unterseeboot or U-boat.

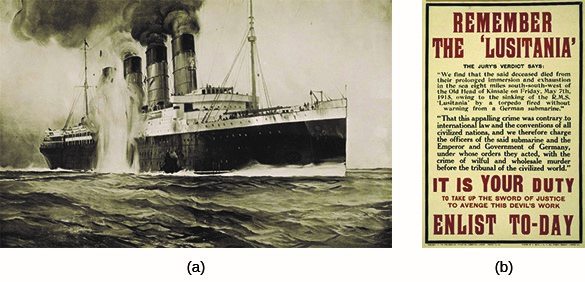

To break the British naval blockade of Germany and turn the tide of the war, Germany dispatched a fleet of U-boats to Great Britain in early 1915 to attack military and merchant ships, including those that carried American goods and American civilians. Rather than surfacing and forcing the civilians and crew members to surrender, the U-boats attacked the ships without warning from below.

EXAMPLE

One of the most notable U-boat attacks occurred on May 7, 1915, when the Lusitania, a British passenger ship traveling from New York City to Liverpool, was sunk. Prior to its departure, the German Embassy in the United States announced that the ship was subject to attack because it was transporting ammunition: an allegation that was later proven true. Almost 1,200 civilians died in the attack, including 128 Americans.

The sinking of the Lusitania and other ships by U-boats revealed that economic factors were driving the United States toward war and away from neutrality. From the earliest days of the war onward, Great Britain and the Allied Powers relied on American imports for their survival.

EXAMPLE

Between 1914 and 1916, the value of American exports to the Allied Powers quadrupled: from $750 million to $3 billion. Many private banks in the United States made large loans—in excess of $500 million—to Great Britain during the war.The British naval blockade virtually eliminated American exports to Germany. However, the goods and money that the United States sent to Great Britain and its allies made it clear that the United States had an economic stake in an Allied victory.

President Wilson ran on a platform of “He Kept Us Out of War” and was reelected after a close race in 1916. Although he tried to avoid sending American troops overseas, Wilson began to see the war as an opportunity for the United States to influence the peace process and expand democracy, free enterprise, and self-determination. On January 22, 1917, Wilson outlined this agenda as a “peace without victory”:

President Woodrow Wilson, January 1917

“The present war must first be ended; but we owe it to candor and to a just regard for the opinion of mankind to say that, so far as our participation in guarantees of future peace is concerned, it makes a great deal of difference in what way and upon what terms it is ended. The treaties and agreements which bring it to an end must embody terms that will create a peace that is worth guaranteeing and preserving, a peace that will win the approval of mankind, not merely a peace that will serve the several interests and immediate aims of the nations engaged . . .

No covenant of cooperative peace that does not include the peoples of the New World can suffice to keep the future safe against war, and yet there is only one sort of peace that the peoples of America could join in guaranteeing.

The elements of that peace must be elements that engage the confidence and satisfy the principles of the American governments, elements consistent with their political faith and with the practical convictions which the peoples of America have once for all embraced and undertaken to defend.”

Wilson’s speech was not well received by either side in the war. Neither wanted to stop fighting until they were sure of the spoils of victory. More importantly, the speech revealed Wilson’s vision for American foreign policy, one in which the United States acted as a mediator while advancing its political and economic interests.

EXAMPLE

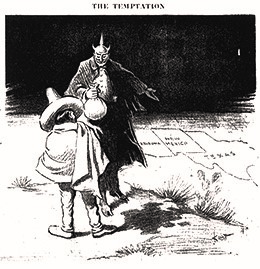

In February 1917, a German U-boat sank an American merchant ship, the Laconia, killing two passengers. In late March, U-boats sunk four more American ships.The final factor that pushed the United States to enter World War I was the Zimmermann Telegram.

News of the Zimmerman telegram, in which Germany offered to return to Mexico the land it lost as a result of the Mexican–American War if it agreed to fight against the United States, was published in March 1917. Along with the continued U-boat attacks, the news increased pressure on Wilson from all sides.

On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, stating that “The world must be made safe for democracy.” After 4 days of deliberation (and despite 56 votes against the resolution), Congress passed the declaration and the United States entered the First World War on the side of the Allied Powers.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Woodrow Wilson, Message on Neutrality, August 20, 1914, Miller Center, bit.ly/2nvYuqX

Woodrow Wilson, “A World League of Peace speech,” January 22, 1917, Miller Center, bit.ly/2nw5F21

Woodrow Wilson, Request of a Declaration of War Against Germany,” April 2, 1917, Miller Center, bit.ly/2ohwVRY