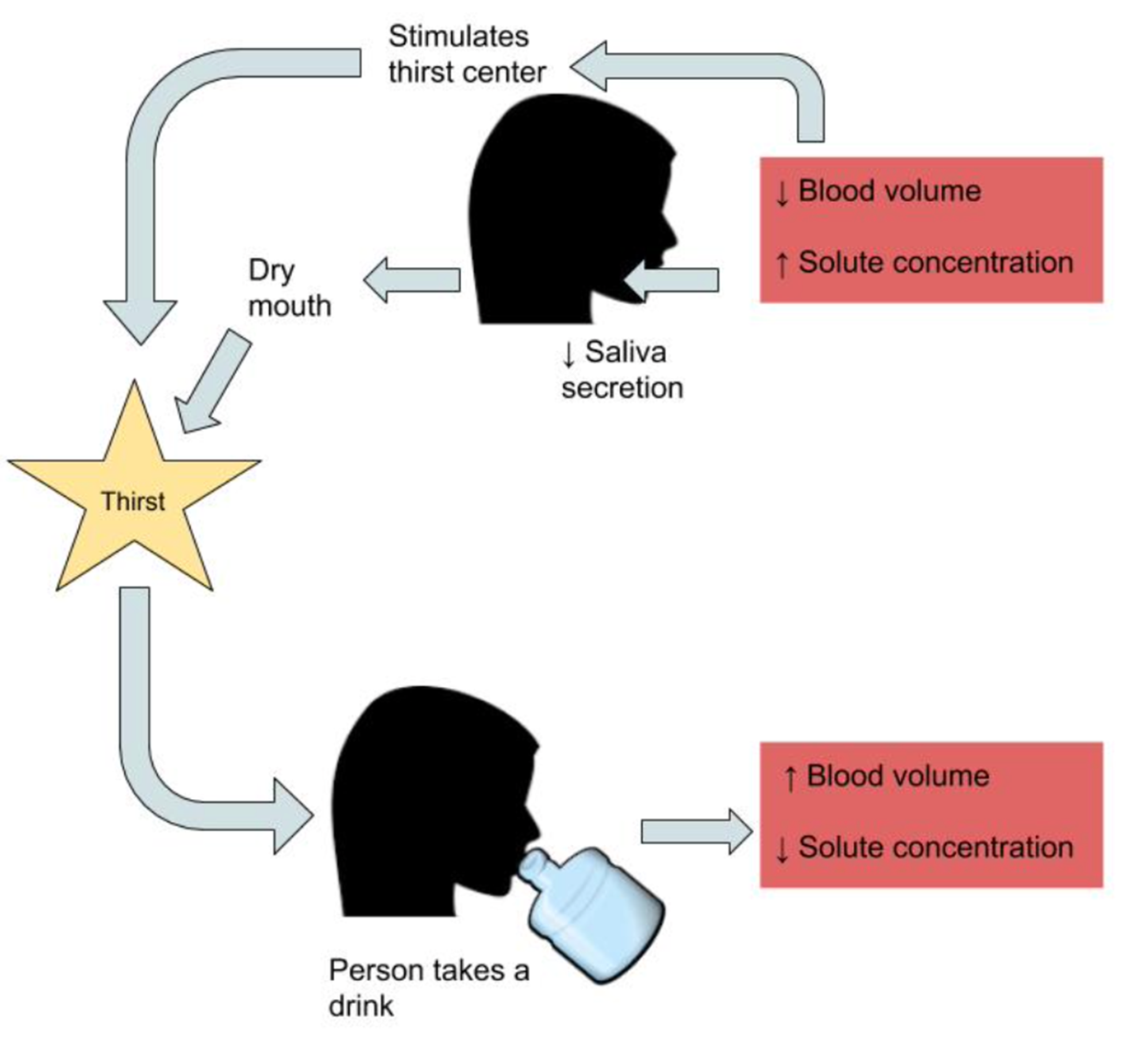

Maintaining the right level of water in your body is crucial to survival, as either too little or too much water in your body will result in less-than-optimal functioning. One mechanism to help ensure the body maintains water balance is thirst. Thirst is the result of your body’s physiology telling your brain to initiate the urge to take a drink. Sensory proteins detect when your mouth is dry, your blood volume too low, or blood electrolyte concentrations are too high and send signals to the brain, stimulating the conscious feeling to drink.

This also means that if a person gains weight in the form of fat, the percentage of total body water content declines. As we age, total body water content also diminishes so that by the time we are in our eighties, the percentage of water in our bodies has decreased to around 45 percent. Water uses in the human body can be loosely categorized into four basic functions: transportation vehicle, medium for chemical reactions, lubricant/shock absorber, and temperature regulator.

Water is called the “universal solvent” because more substances dissolve in it than any other fluid. Molecules dissolve in water because of the hydrogen and oxygen molecules ability to loosely bond with other molecules. Molecules of water  surround substances, suspending them in a sea of water molecules.

surround substances, suspending them in a sea of water molecules.

The solvent action of water allows for substances to be more readily transported. A pile of undissolved salt would be difficult to move throughout tissues, as would a bubble of gas or a glob of fat. Blood, the primary transport fluid in the body, is about 78 percent water. Dissolved substances in blood include proteins, lipoproteins, glucose, electrolytes, and metabolic waste products, such as carbon dioxide and urea. These substances are either dissolved in the watery surroundings of blood to be transported to cells to support basic functions or are removed from cells to prevent waste build-up and toxicity.

Water is required for even the most basic chemical reactions. Proteins fold into their functional shape based on how their amino-acid sequences react with water. These newly formed enzymes must conduct their specific chemical reactions in a medium, which in all organisms is water.

Many may view the slimy products of a sneeze as gross, but sneezing is essential for removing irritants and could not take place without water. Mucus, which is not only essential to discharge nasal irritants, is also required for breathing, transportation of nutrients along the gastrointestinal tract, and elimination of waste materials through the rectum. Mucus is composed of more than 90 percent water and a frontline defense against injury and foreign invaders. It protects tissues from irritants, entraps pathogens, and contains immune-system cells that destroy pathogens.

Water is also the main component of the lubricating fluid between joints and eases the movement of articulated bones. The aqueous and vitreous humors, which are fluids that fill the extra space in the eyes and the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, are primarily water and buffer these organs against sudden changes in the environment.

Watery fluids surrounding organs provide both chemical and mechanical protection. Just two weeks after fertilization, water fills the amniotic sac in a pregnant woman, providing a cushion of protection for the developing embryo.

Another homeostatic function of the body, termed thermoregulation, is to balance heat gain with heat loss, and body water plays an important role in accomplishing this. Human life is supported within a narrow range of temperature, with the temperature set point of the body being 98.6°F (37°C).

There are several mechanisms in place that move body water from place to place as a method to distribute heat in the body and equalize body temperature. The hypothalamus in the brain is the thermoregulatory center. The hypothalamus contains special protein sensors that detect blood temperature. The skin also contains temperature sensors that respond quickly to changes in immediate surroundings. In response to cold sensors in the skin, a neural signal is sent to the hypothalamus, which then sends a signal to smooth muscle tissue surrounding blood vessels, causing them to constrict and reduce blood flow. This reduces heat lost to the environment.

The hypothalamus also sends signals to muscles to erect hairs and shiver and to endocrine glands like the thyroid to secrete hormones capable of ramping up metabolism. These actions increase heat conservation and stimulate its production in the body in response to cooling temperatures. Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to maintain body temperature despite changing environmental temperatures.

IN CONTEXT

As you eat a bite of food, the salivary glands secrete saliva. As the food enters your stomach, gastric juice is secreted. As it enters the small intestine, pancreatic juice is secreted. Each of these fluids contains a great deal of water. How is that water replaced in these organs? What happens to the water now in the intestines? In a day, there is an exchange of about 10 liters of water among the body’s organs. The osmoregulation of this exchange involves complex communication between the brain, kidneys, and endocrine system. A homeostatic goal for a cell, a tissue, an organ, and an entire organism is to balance water output with water input.

Total water output per day averages 2.5 liters. This must be balanced with water input. Our tissues produce around 300 milliliters of water per day through metabolic processes. The remainder of water output must be balanced by drinking fluids and eating solid foods. The average fluid consumption per day is 1.5 liters, and water gained from solid foods approximates 700 milliliters.

The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has set the Adequate Intake (AI) for water for adult males at 3.7 liters (15.6 cups) and at 2.7 liters (11 cups) for adult females. These intakes are higher than the average intake of 2.2 liters.

| Water Content in Foods | |

|---|---|

| Percentage | Food Item |

| 90–99 | Nonfat milk, cantaloupe, strawberries, watermelon, lettuce, cabbage, celery, spinach, squash |

| 80–89 | Fruit juice, yogurt, apples, grapes, oranges, carrots, broccoli, pears, pineapple |

| 70–79 | Bananas, avocados, cottage cheese, ricotta cheese, baked potato, shrimp |

| 60–69 | Pasta, legumes, salmon, chicken breast |

| 50–59 | Ground beef, hot dogs, steak, feta cheese |

| 40–49 | Pizza |

| 30–39 | Cheddar cheese, bagels, bread |

| 20–29 | Pepperoni, cake, biscuits |

| 10–19 | Butter, margarine, raisins |

| 1–9 | Walnuts, dry-roasted peanuts, crackers, cereals, pretzels, peanut butter |

| 0 | Oils, sugars |

There is some debate over the amount of water required to maintain health because there is no consistent scientific evidence proving that drinking a particular amount of water improves health or reduces the risk of disease. In fact, kidney-stone prevention seems to be the only premise for water-consumption recommendations. The amount of water/fluids a person should consume every day is actually variable and should be based on the climate a person lives in, as well as their age, physical activity level, and kidney function. No maximum for water intake has been set.

Thirst is an osmoregulatory mechanism to increase water input. The thirst mechanism is activated in response to changes in water volume in the blood, but is even more sensitive to changes in blood osmolality. Blood osmolality is primarily driven by the concentration of sodium cations. The urge to drink results from a complex interplay of hormones and neuronal responses that coordinate to increase water input and contribute toward fluid balance and composition in the body. The “thirst center” is contained within the hypothalamus, a portion of the brain that lies just above the brainstem. In older people, the thirst mechanism is not as responsive, and as we age, there is a higher risk for dehydration. Thirst happens in the following sequence of physiological events:

The physiological control of thirst is the backup mechanism to increase water input. Fluid intake is controlled primarily by conscious eating and drinking habits dependent on social and cultural influences. For example, you might have a habit of drinking a glass of orange juice and eating a bowl of cereal every morning before school or work.

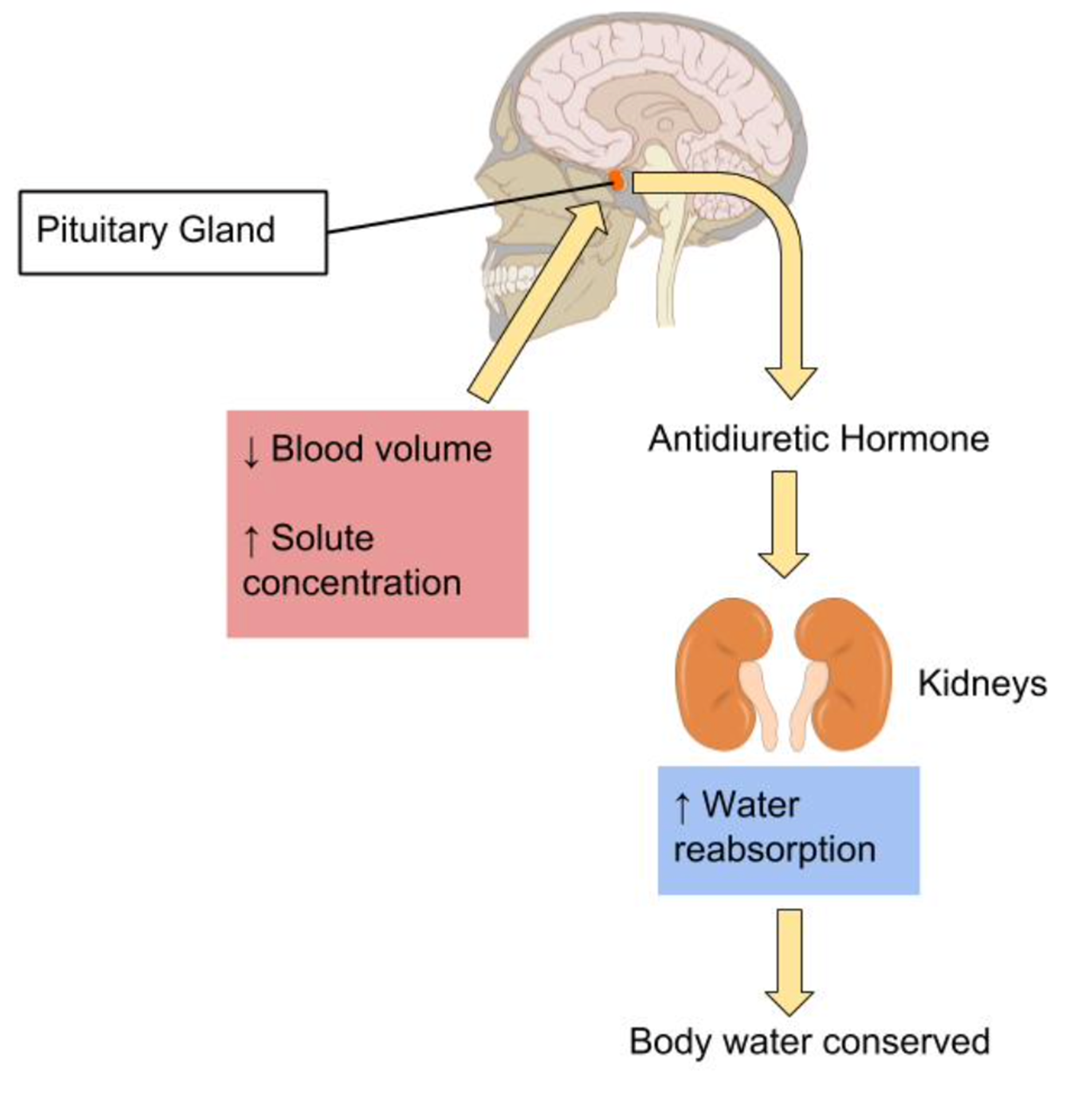

As stated, daily water output averages 2.5 liters. There are two types of outputs. The first type is insensible water loss, meaning we are unaware of it. The body loses about 400 milliliters of its daily water output through exhalation. Another 500 milliliters is lost through our skin. The second type of output is sensible water loss, meaning we are aware of it. Urine accounts for about 1,500 milliliters of water output, and feces account for roughly 100 milliliters of water output. Regulating urine output is a primary function of the kidneys and involves communication with the brain and endocrine system.

The kidneys filter about 190 liters of blood and produce (on average) 1.5 liters of urine per day. Urine is mostly water, but it also contains electrolytes and waste products, such as urea. The amount of water filtered from the blood and excreted as urine is dependent on the amount of water in and the electrolyte composition in the blood.

Kidneys have protein sensors that detect blood volume from the pressure, or stretch, in the blood vessels of the kidneys. When blood volume is low, kidney cells detect decreased pressure and secrete the enzyme, renin. Renin travels in the blood and cleaves another protein into the active hormone, angiotensin. Angiotensin targets three different organs (the adrenal glands, the hypothalamus, and the muscle tissue surrounding the arteries) to rapidly restore blood volume and, consequently, pressure.

Contaminated water is estimated to result in more than half a million deaths per year. Contaminated water and the lack of sanitation were estimated to cause about 1 percent of disability adjusted life years worldwide in 2010.

From 2000–2003, 769,000 children under five years old in sub-Saharan Africa died each year from diarrheal diseases. As a result of only 36 percent of the population in the sub-Saharan region having access to proper means of sanitation, more than 2,000 children’s lives are lost every day. In South Asia, 683,000 children under five years old died each year from diarrheal disease from 2000–2003. During the same time period, in developed countries, 700 children under five years old died from diarrheal disease.

IN CONTEXT

Improved water supply reduces diarrhea morbidity by 25 percent, and improvements in drinking water through proper storage in the home and chlorination reduce diarrhea episodes by 39 percent.

Parameters for drinking water quality typically fall under three categories: physical, chemical, and microbiological.

Physical and chemical parameters include heavy metals, trace organic compounds, total suspended solids (TSS), and turbidity. Microbiological parameters include Coliform bacteria, E. coli, and specific pathogenic species of bacteria (such as cholera-causing Vibrio cholerae), viruses, and protozoan parasites. Chemical parameters tend to pose more of a chronic health risk through buildup of heavy metals, although some components like nitrates/nitrites and arsenic can have a more immediate impact. Physical parameters affect the aesthetics and taste of the drinking water and may complicate the removal of microbial pathogens.

Throughout most of the world, the most common contamination of raw water sources is from human sewage and, in particular, human fecal pathogens and parasites.

It is clear that people in the developing world need to have access to good quality water in sufficient quantity, water purification technology, and availability and distribution systems for water. In many parts of the world, the only sources of water are from small streams, often directly contaminated by sewage.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING’S “NUTRITION FLEXBOOK”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-nutrition/. LICENSE: creative commons attribution 4.0 international.

REFERENCES

National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23. US Department of Agriculture,