Table of Contents |

Although leukocytes and erythrocytes both originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow, they are very different from each other in many significant ways. Leukocytes:

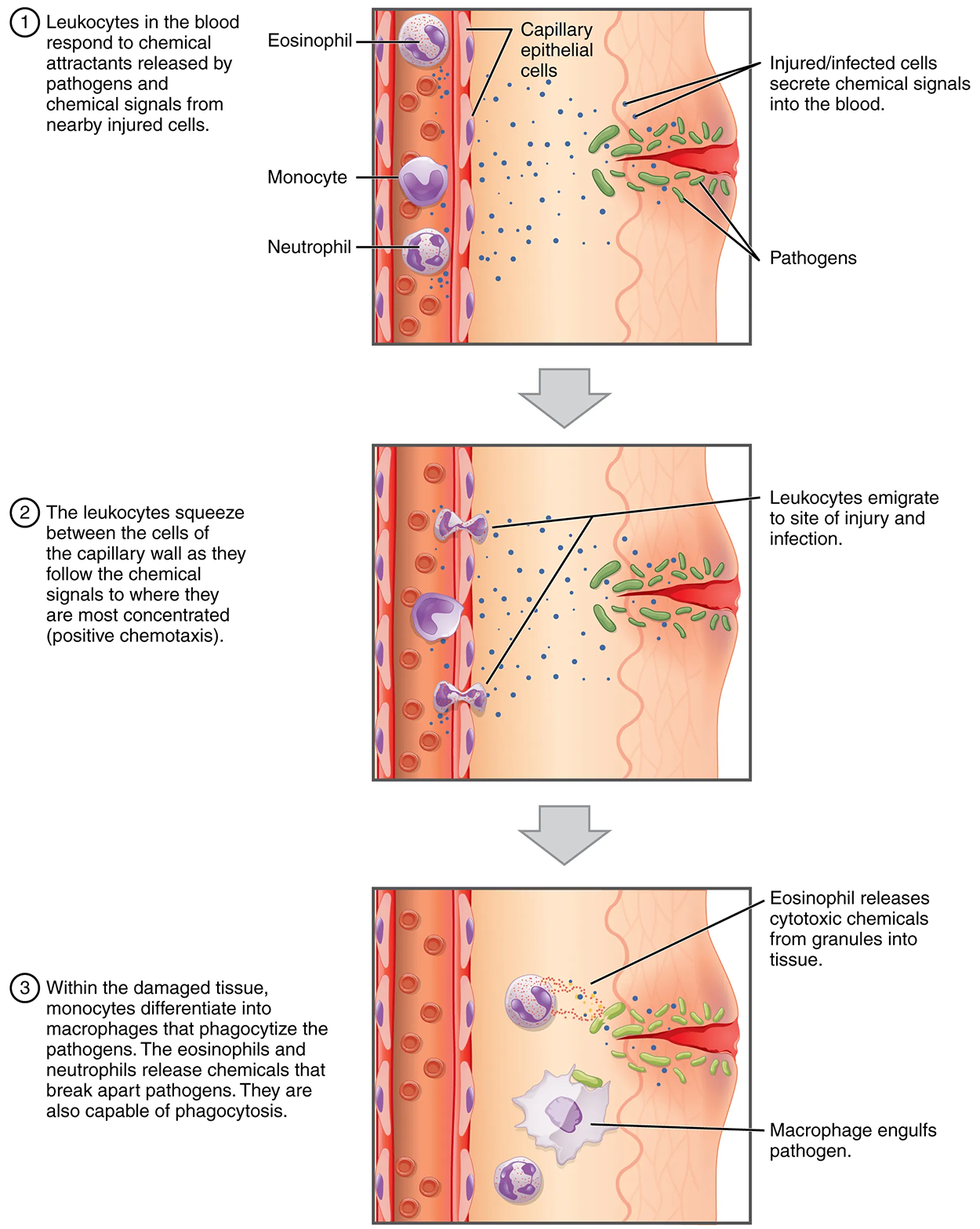

One of the most distinctive characteristics of leukocytes is their movement. Whereas erythrocytes spend their days circulating within the blood vessels, leukocytes routinely leave the bloodstream to perform their defensive functions in the body’s tissues. For leukocytes, the vascular network is simply a highway they travel and soon exit to reach their true destination.

When they arrive, they are often given distinct names, such as macrophage or microglia, depending on their function. Leukocytes are capable of squeezing through adjacent cells in the blood vessel wall, a process known as diapedesis (dia, through; pedan, to leap), which occurs primarily through capillaries—the smallest blood vessels—or other small vessels.

Once they have exited the capillaries, some leukocytes will take up fixed positions in lymphatic tissue, bone marrow, the spleen, the thymus, or other organs. Others will move about through the tissue spaces very much like amoebas, continuously extending their plasma membranes, sometimes wandering freely and sometimes moving toward the direction in which they are drawn by chemical signals. This attracting of leukocytes occurs because of positive chemotaxis (movement towards a chemical signal), a phenomenon in which injured or infected cells and nearby leukocytes emit the equivalent of a chemical “911” call, attracting more leukocytes to the site.

When scientists first began to observe stained blood slides, it quickly became evident that leukocytes could be divided into two groups, according to whether their cytoplasm contained highly visible granules:

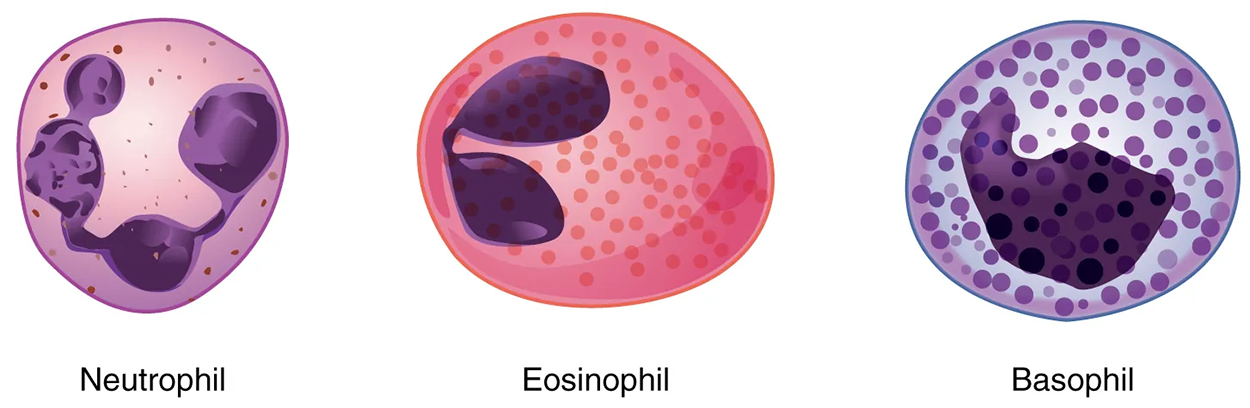

All granular leukocytes are produced in the red bone marrow and have a short lifespan of hours to days. They typically have a lobed nucleus and are classified according to which type of stain best highlights their granules.

The most common of all the leukocytes, neutrophils will normally comprise 50%–70% of total leukocyte count. They are 10–12 µm in diameter, significantly larger than erythrocytes. They are called neutrophils because their granules show up most clearly with stains that are chemically neutral (neither acidic nor basic). The granules are numerous but quite fine and normally appear light lilac. The nucleus has a distinct lobed appearance and may have two to five lobes, the number increasing with the age of the cell.

Neutrophils are rapid responders to the site of infection and are efficient phagocytes with a preference for bacteria. Their granules include lysozyme, an enzyme capable of lysing, or breaking down, bacterial cell walls; oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide; and defensins, proteins that bind to and puncture bacterial and fungal plasma membranes so that the cell contents leak out.

IN CONTEXT

Abnormally high counts of neutrophils indicate infection and/or inflammation, particularly triggered by bacteria, but are also found in burn patients and others experiencing unusual stress. A burn injury increases the proliferation of neutrophils to fight off infection that can result from the destruction of the barrier of the skin. Low counts may be caused by drug toxicity and other disorders, and may increase an individual’s susceptibility to infection.

Eosinophils typically represent 2%–4% of total leukocyte count. They are also 10–12 µm in diameter. The granules of eosinophils stain best with an acidic stain known as eosin. The nucleus of the eosinophil will typically have two to three lobes and, if stained properly, the granules will have a distinct red to orange color.

The granules of eosinophils include antihistamine molecules, which counteract the activities of histamines, inflammatory chemicals produced by basophil cells. Some eosinophil granules contain molecules toxic to parasitic worms, which can enter the body through the integument, or when an individual consumes raw or undercooked fish or meat. Eosinophils are also capable of phagocytosis and are particularly effective when antibodies bind to the target and form an antigen–antibody complex.

IN CONTEXT

High counts of eosinophils are typical of patients experiencing allergies, parasitic worm infestations, and some autoimmune diseases. Low counts may be due to drug toxicity and stress.

Basophils are the least common leukocytes, typically comprising less than 1% of the total leukocyte count. They are slightly smaller than neutrophils and eosinophils at 8–10 µm in diameter. The granules of basophils stain best with basic (alkaline) stains. Basophils contain large granules that pick up a dark blue stain and that are so common, they may make it difficult to see the two-lobed nucleus.

In general, basophils intensify the inflammatory response by releasing inflammatory chemicals. The granules of basophils release histamines, which contribute to inflammation, and heparin, which opposes blood clotting.

IN CONTEXT

High counts of basophils are associated with allergies, parasitic infections, and hypothyroidism. Low counts are associated with pregnancy, stress, and hyperthyroidism.

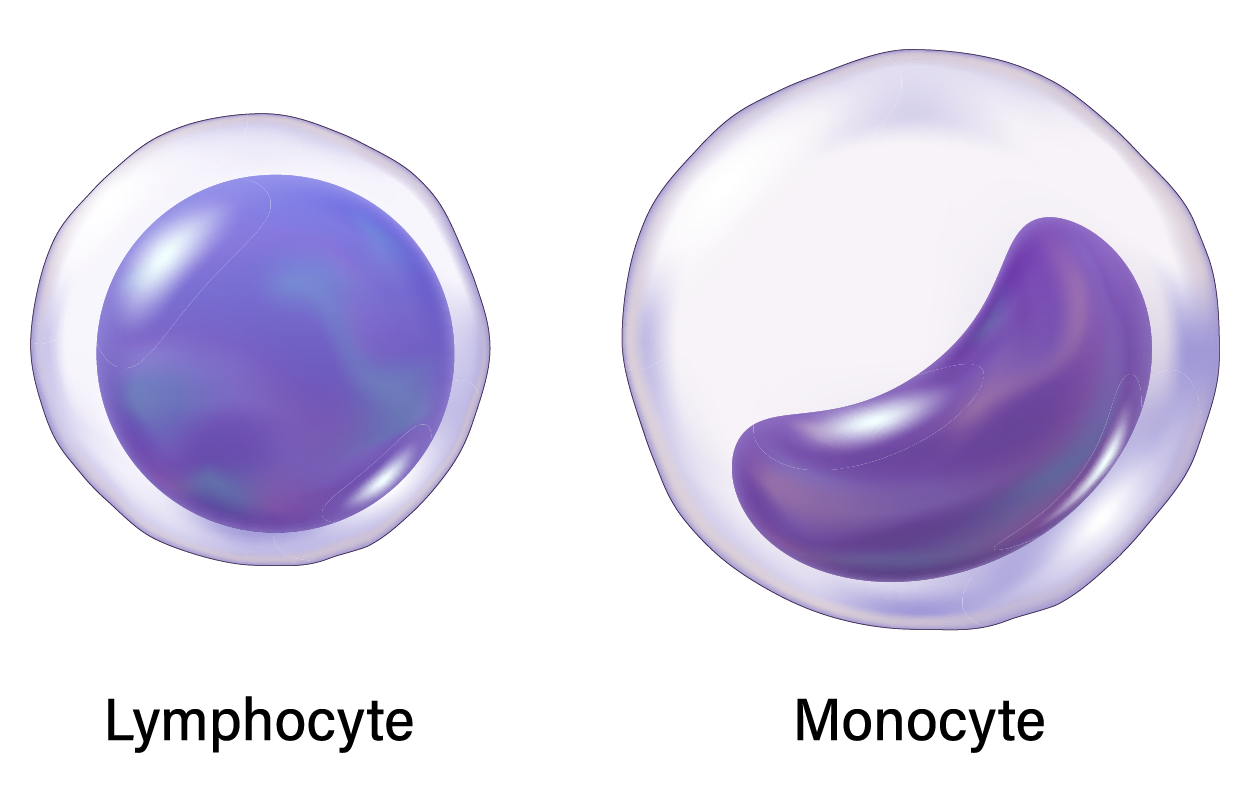

Agranular leukocytes contain smaller, less-visible granules in their cytoplasm than do granular leukocytes. The nucleus is simple in shape, sometimes with an indentation but without distinct lobes. There are two major types of agranulocytes: lymphocytes and monocytes.

Lymphocytes are the only formed element of blood that arises from lymphoid stem cells. Although they form initially in the bone marrow, much of their subsequent development and reproduction occurs in the lymphatic tissues. Lymphocytes are the second most common type of leukocyte, accounting for about 20%–30% of all leukocytes, and are essential for the immune response. The size range of lymphocytes is quite extensive, with some authorities recognizing two size classes and others, three.

The three major groups of lymphocytes include natural killer cells, B cells, and T cells. You will learn more about these specific cells in the lymphatic system, as they play prominent roles in defending the body against specific pathogens (disease-causing microorganisms) and are involved in specific immunity.

IN CONTEXT

Abnormally high lymphocyte counts are characteristic of viral infections as well as some types of cancer. Abnormally low lymphocyte counts are characteristic of prolonged (chronic) illness or immunosuppression, including that caused by HIV infection and drug therapies that often involve steroids.

Monocytes originate from myeloid stem cells. They normally represent 2–8% of the total leukocyte count. They are typically easily recognized by their large size of 12–20 µm and indented or horseshoe-shaped nuclei. Macrophages are monocytes that have left the circulation and phagocytize debris, foreign pathogens, worn-out erythrocytes, and many other dead, worn-out, or damaged cells. Macrophages also release antimicrobial defensins and chemotactic chemicals that attract other leukocytes to the site of an infection. Some macrophages occupy fixed locations, whereas others wander through the tissue fluid.

Abnormally high counts of monocytes are associated with viral or fungal infections, tuberculosis, and some forms of leukemia and other chronic diseases. Abnormally low counts are typically caused by suppression of the bone marrow.

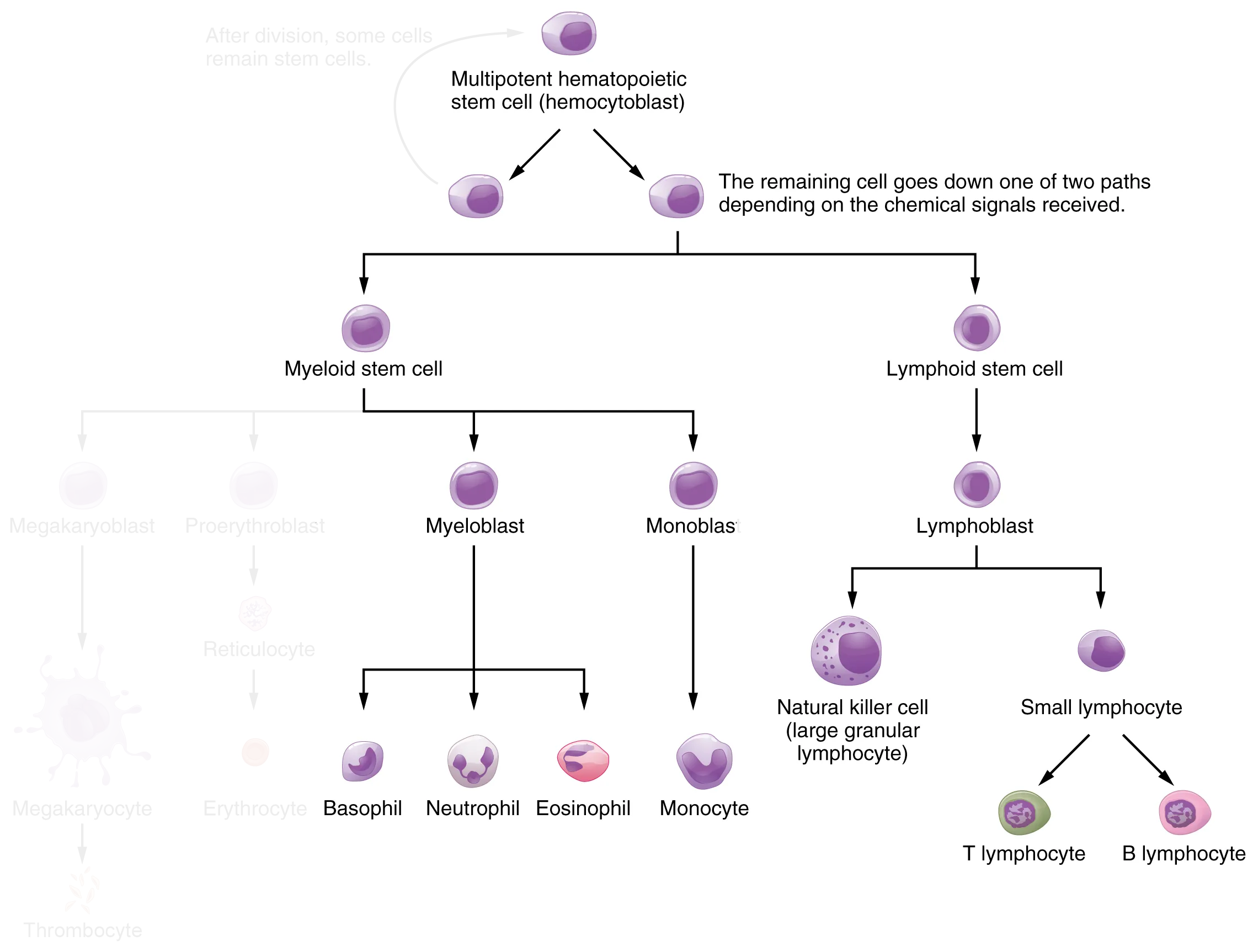

As you know, all formed elements are produced from hematopoiesis, which begins in the bone marrow. The specific pathways within hematopoiesis that form the five types of leukocytes are collectively known as leukopoiesis. This process of differentiation is influenced by two classes of cytokines, namely colony-stimulating factors and interleukins. Specific versions of these cytokines cause the stem cells to differentiate into different types of leukocytes.

At the start, the hematopoietic stem cell can differentiate into a myeloid or lymphoid stem cell. The myeloid stem cell can differentiate into a myeloblast, which will give rise to all granular leukocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), or a monoblast, which gives rise to monocytes. The lymphoid stem cell differentiates into a lymphoblast, which can give rise to all three forms of lymphocytes.

Most leukocytes have a relatively short lifespan, typically measured in hours or days. Production of all leukocytes begins in the bone marrow under the influence of cytokine signaling factors and interleukins. Secondary production and maturation of lymphocytes occur in specific regions of peripheral lymphatic tissue.

Lymphocytes are fully capable of mitosis and may produce clones of cells with identical properties. This capacity enables an individual to maintain immunity throughout life to many threats that have been encountered in the past.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.