Table of Contents |

We’ve learned that truth tables can show us that an argument is valid or invalid, but it is less useful in showing why an argument is valid or invalid. Consider this argument:

| P | Q | P ∨ Q | ¬P | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | T | F | F |

| F | F | F | T | F |

But you probably don’t need a truth table to see that it is valid; if at least one of two things is true and one is removed from consideration, the other must be true. Furthermore, the truth table does not “explain” this premise or aid our understanding; it is a purely mechanical tool. By a mechanical tool, what we mean is that a truth table basically functions as a nondigital calculator. It cranks through every possibility and delivers an answer without really understanding or needing you to understand why the answer is what it is. It’s very similar to being able to plug in a math problem to a calculator and get a result even when you don’t know how to do that computation by hand. In this way, truth tables are a little bit like cheating, since they allow us to determine validity without deeply understanding the rules and structure of our logical language.

Another issue with truth tables is that for some arguments with lots of atomic sentences and several premises, a truth table becomes overly long and tedious to complete.

EXAMPLE

Consider this argument:

In principle, we can set a machine to grind through truth tables and report back when it is finished. In practice, complicated arguments in formal logic can become unwieldy if we use truth tables. Truth tables have limited usefulness in helping us sharpen our reasoning skills by analyzing arguments.

Another way to show not only that arguments are valid, but why they are valid, is by constructing a proof. A proof is a method for demonstrating the validity of a logical argument based on basic rules of inference. The rules of inference tell us what logical sentences follow from what other logical sentences. Essentially, a proof is a logical argument where we “show our work,” like you may have had to do in math class.

When we construct a proof, we show that an argument is valid, and demonstrate why that is the case. Proofs are thus more efficient than truth tables, especially for arguments with several atomic and complex sentences, and have the additional benefit of giving insight into the reasoning behind the argument or explaining it to others.

The development of a proof also poses more of a challenge to the logician than developing a truth table. Writing a proof requires us to understand and use the rules of logic in creative ways.

In this challenge, we will learn what proofs look like, memorize some basic rules of inference that are employed in constructing proofs, and then construct a few proofs of our own. You may be a bit daunted at first, but trust that proofs will be a great asset to critical thinking. While knowing logic has helped us translate and test arguments for validity, proofs teach us how to grasp the reasoning behind arguments and give us a way to explain our reasoning to others.

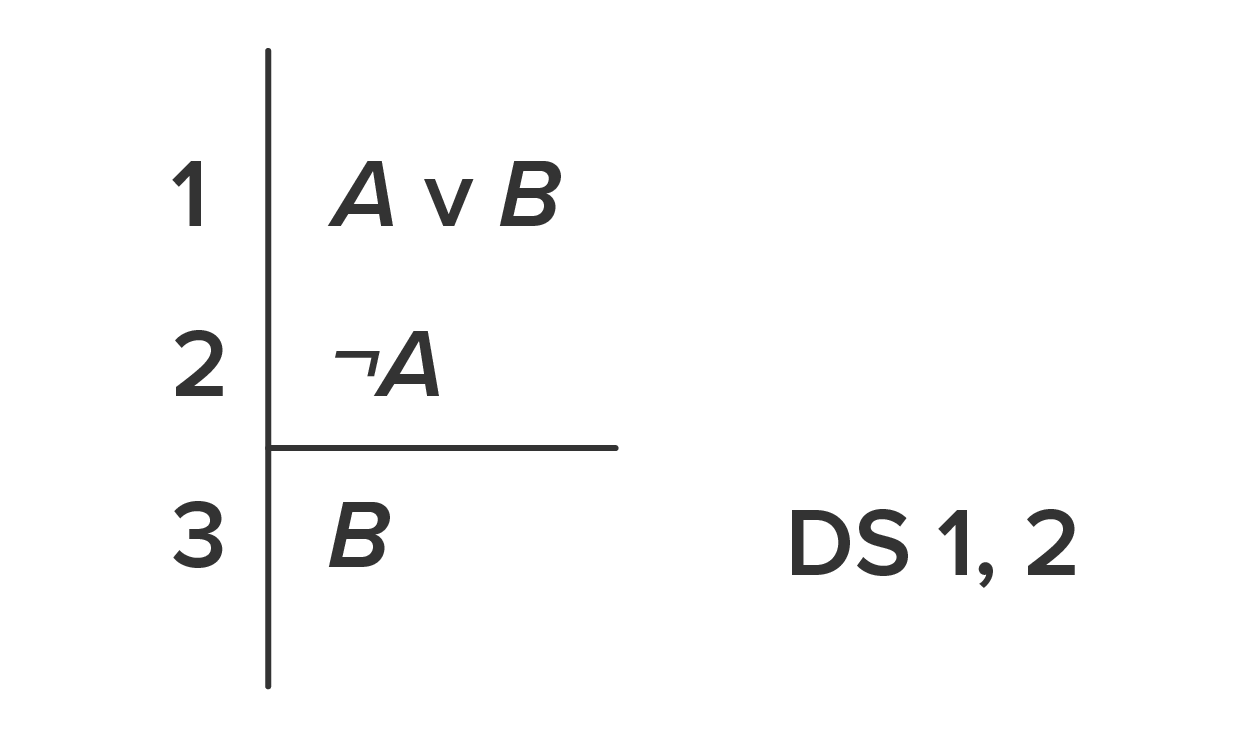

There are multiple notations that symbolize the same logical concept. For example, while we’ve been using the arrow, →, to represent a conditional sentence, others use the horseshoe, ⊃. There is also more than one way to notate proofs. While the reasoning is the same, the proofs may look different. The practice we’ll follow in this class is called the Fitch System, developed by Frederich Fitch in 1952. Here is an example of a proof in this system.

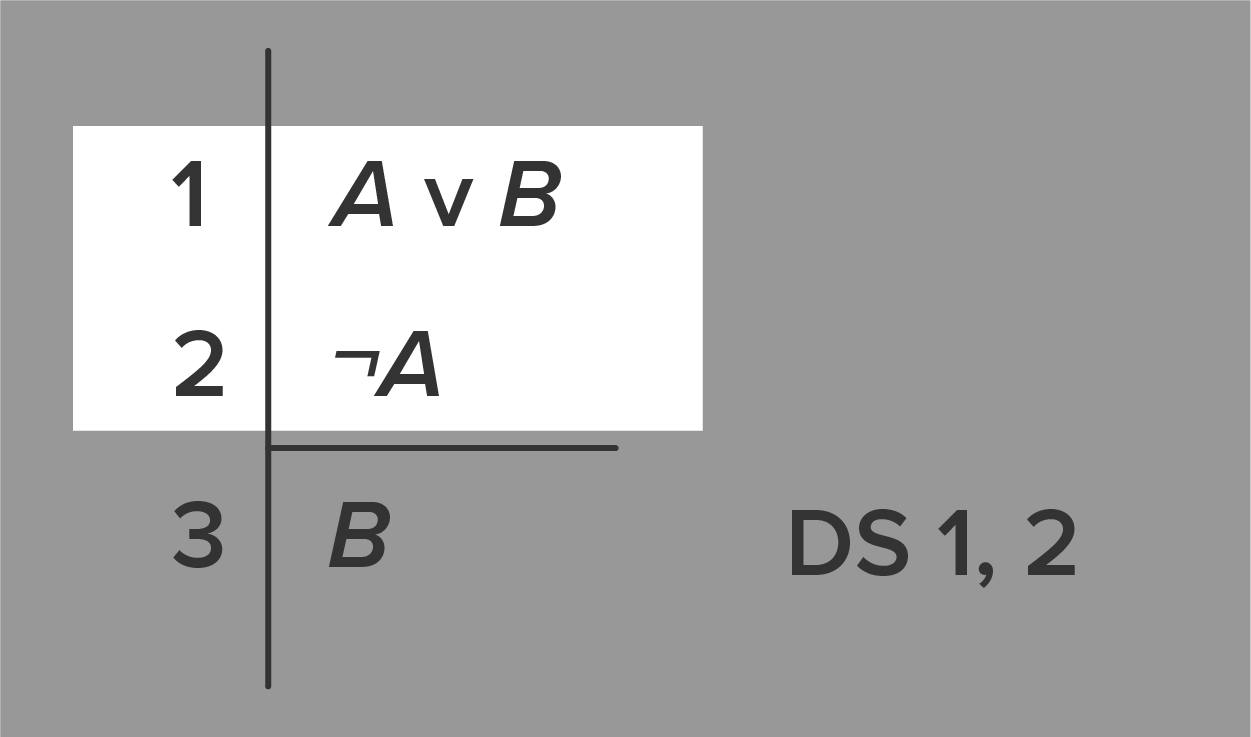

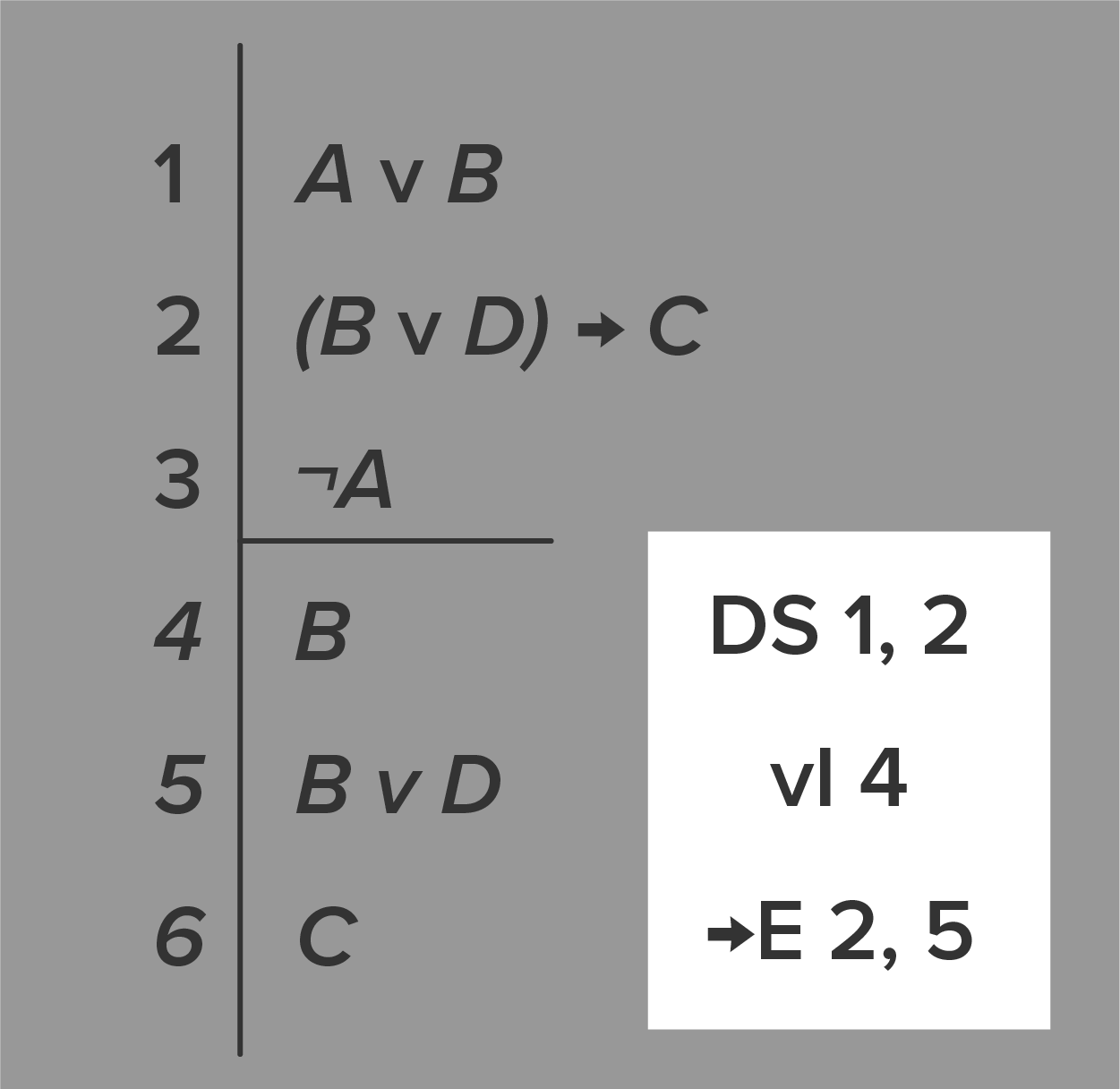

You may notice that the proof looks a bit like an argument. There are numbered lines with premises and a conclusion. Of course, there are differences as well: we have a horizontal line under our premises, a vertical line between the numbers and the statements, and the conclusion has a mysterious tag to the right, “DS 1,2.” What do all of these things mean?

First, the sentences above the horizontal line are our premises. We assume that our starting premises are true, or in other words, we take their truth for granted. In this way, they’re like the assumptions we’ve discussed in earlier tutorials. Premises are the starting assumptions that get us to the conclusion.

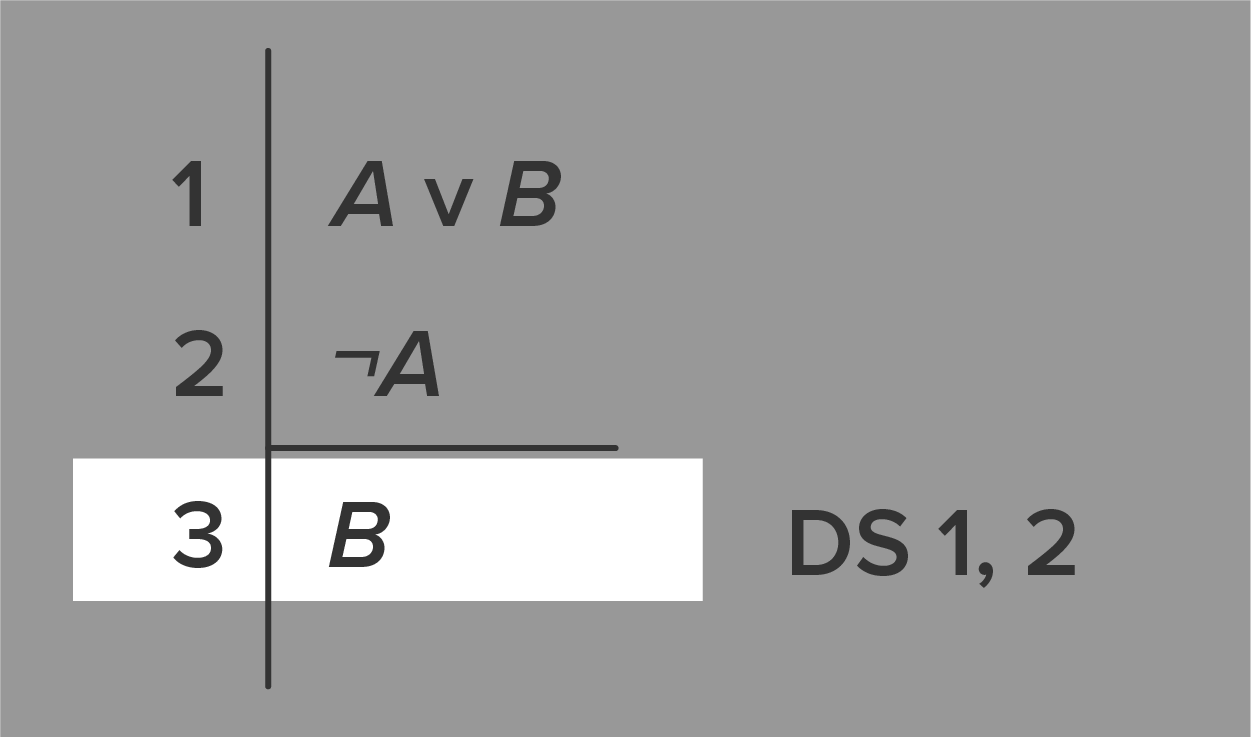

As with arguments, the bottom line is the conclusion.

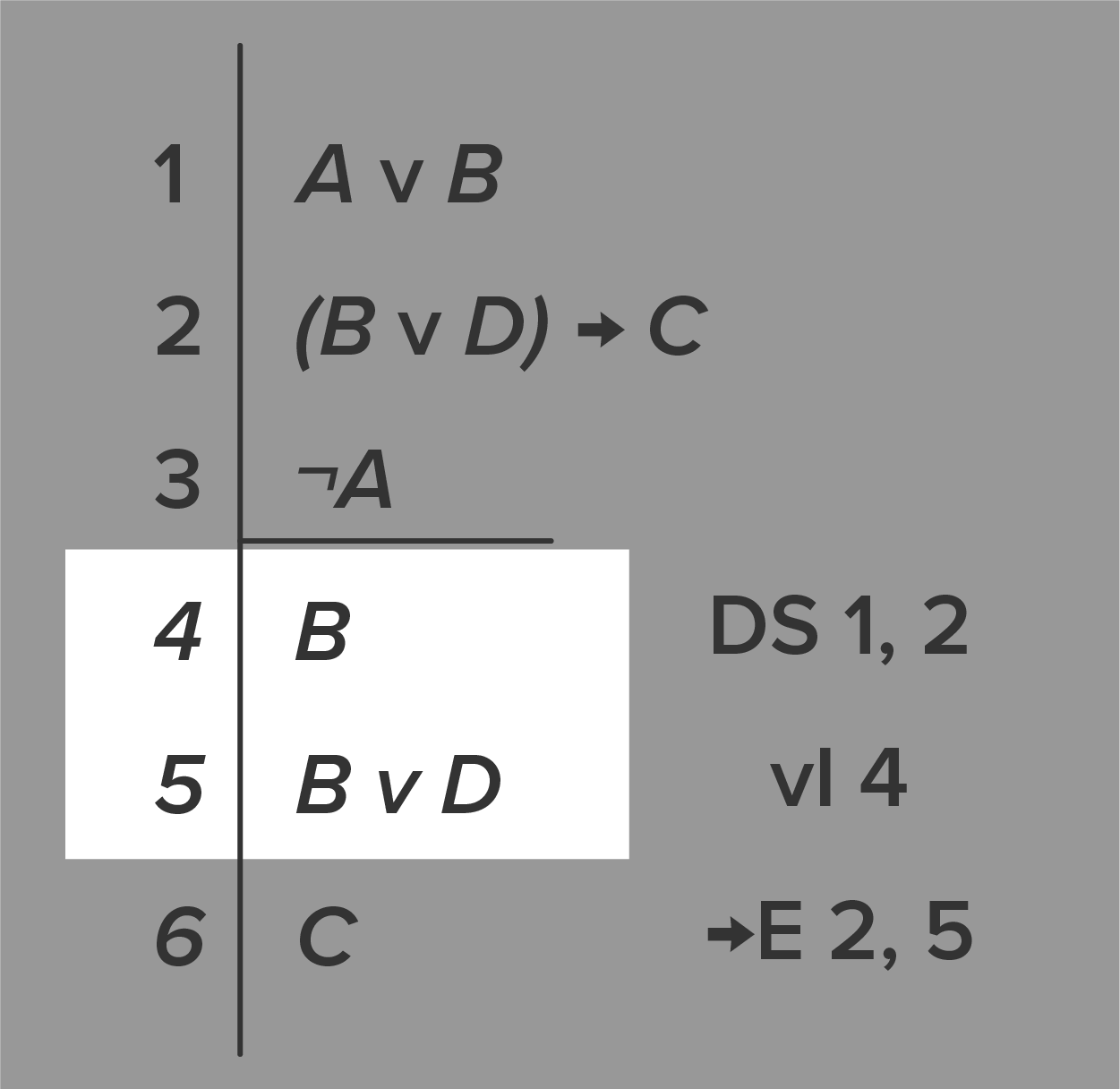

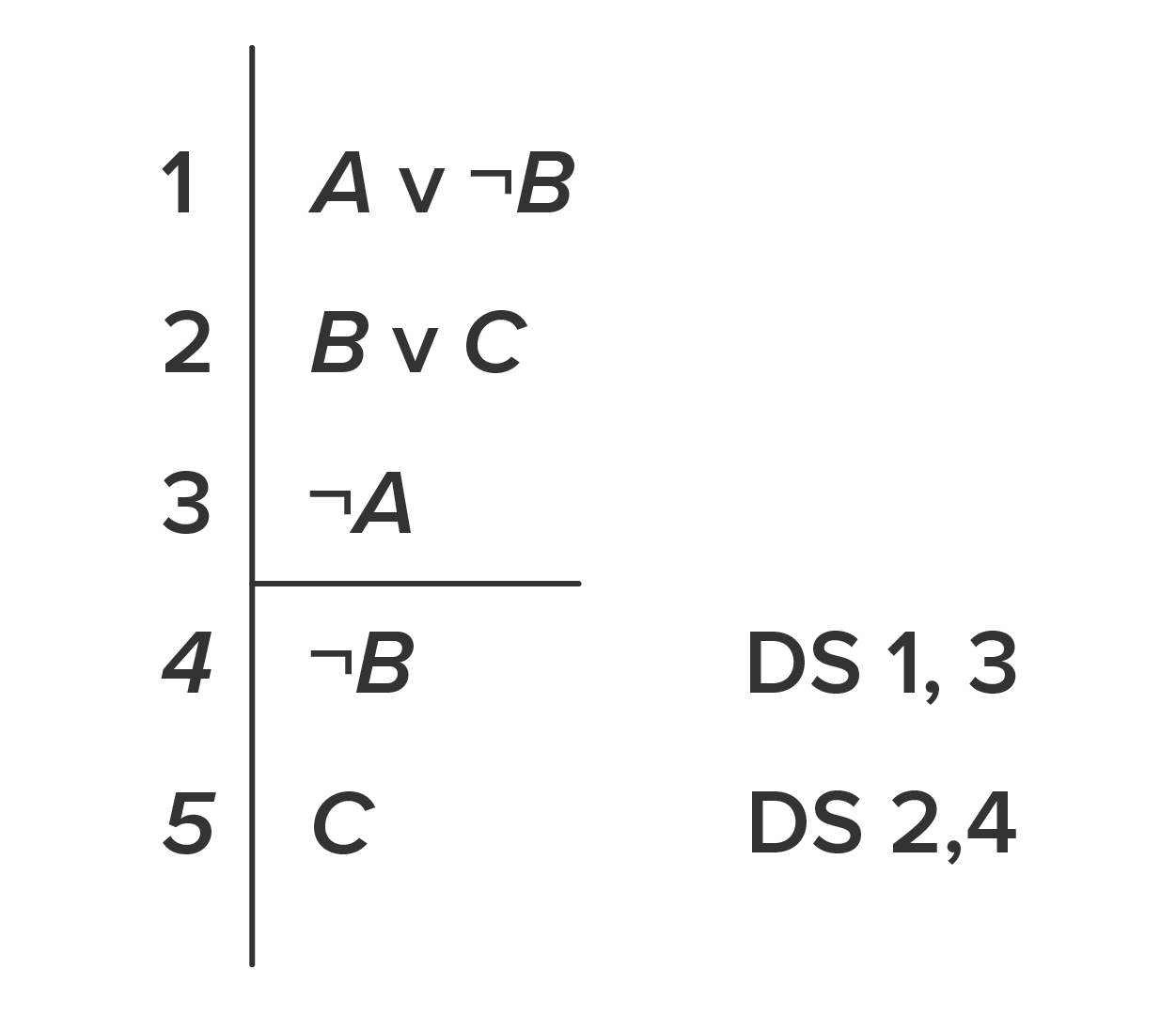

Why the horizontal line? The example above has no sentences other than the premises and the conclusion, but other proofs might require additional steps, called derivations. These are neither premises nor conclusions, but sentences whose truth we have inferred (derived) from the premises and our inference rules of logic. They show how we are working toward the conclusion. One way to think about derivations is as subconclusions required to get us to the main conclusion. In this next example, the 4th and 5th lines are derivations.

The purpose of the horizontal line is thus to separate the premises from the derivations and conclusion.

Finally, you will see the derivations and the conclusion all have letters, symbols, and numbers at the right. These notations show how we derived the sentences on each line. The left part names the rule of inference used (in shorthand) and the numbers indicate the previous sentences we applied the rules to. Of course you have not yet learned the rules of inference, so these may be a bit mysterious, but for now it’s important to recognize the parts of a proof when you see one.

Consider this argument in natural language.

The other person might try to explain by reconstructing a hidden premise/assumption:

If we assigned constants to these statements, we would get:

So, why does the subpremise B help us? In obvious terms, it gets us to a subconclusion that helps us derive the main conclusion. But as it’s not a starting premise, when we adopt a subpremise, we must discharge it by the end of the subproof. To discharge a premise means that we no longer assume that it’s true. We do that by taking whatever subconclusion we’ve arrived at, and conditionalizing the subconclusion on the subpremise. That is, creating a conditional sentence where the subpremise is the antecedent and the subconclusion is the consequent.

Before continuing with our proof, let’s pause to think about why conditionals are so helpful in proofs. In a proof, we cannot arbitrarily make assumptions about what is or isn’t true. Our starting premises are the only truths that we can be certain about. So, conditionals are helpful because they give us what we call hypothetical truths—that is, things that we could learn are true given a set of conditions. To bring it back to a previous discussion, conditions allow us to explore possible truths. And those possible truths end up being things we might conclude in a proof given certain conditions, i.e., the truth of the antecedent.

Conditionals are powerful. In a proof, they set up conditions (antecedents) required to fulfill whatever is on the right-hand side (the consequent). If we can get ourselves to the truth of the right set of conditions, and we can get ourselves the right set of conditions, what we want to conclude becomes straightforward.

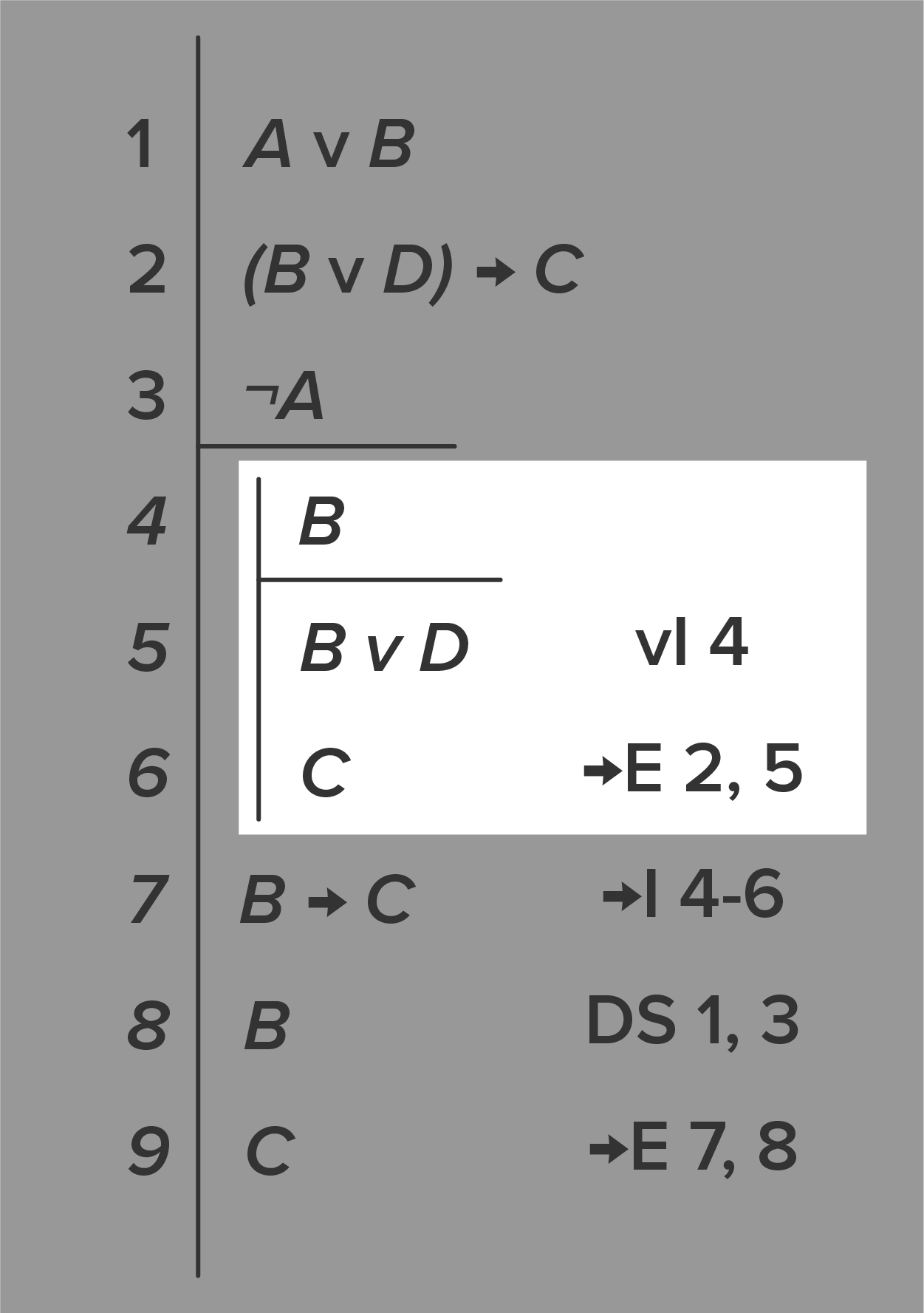

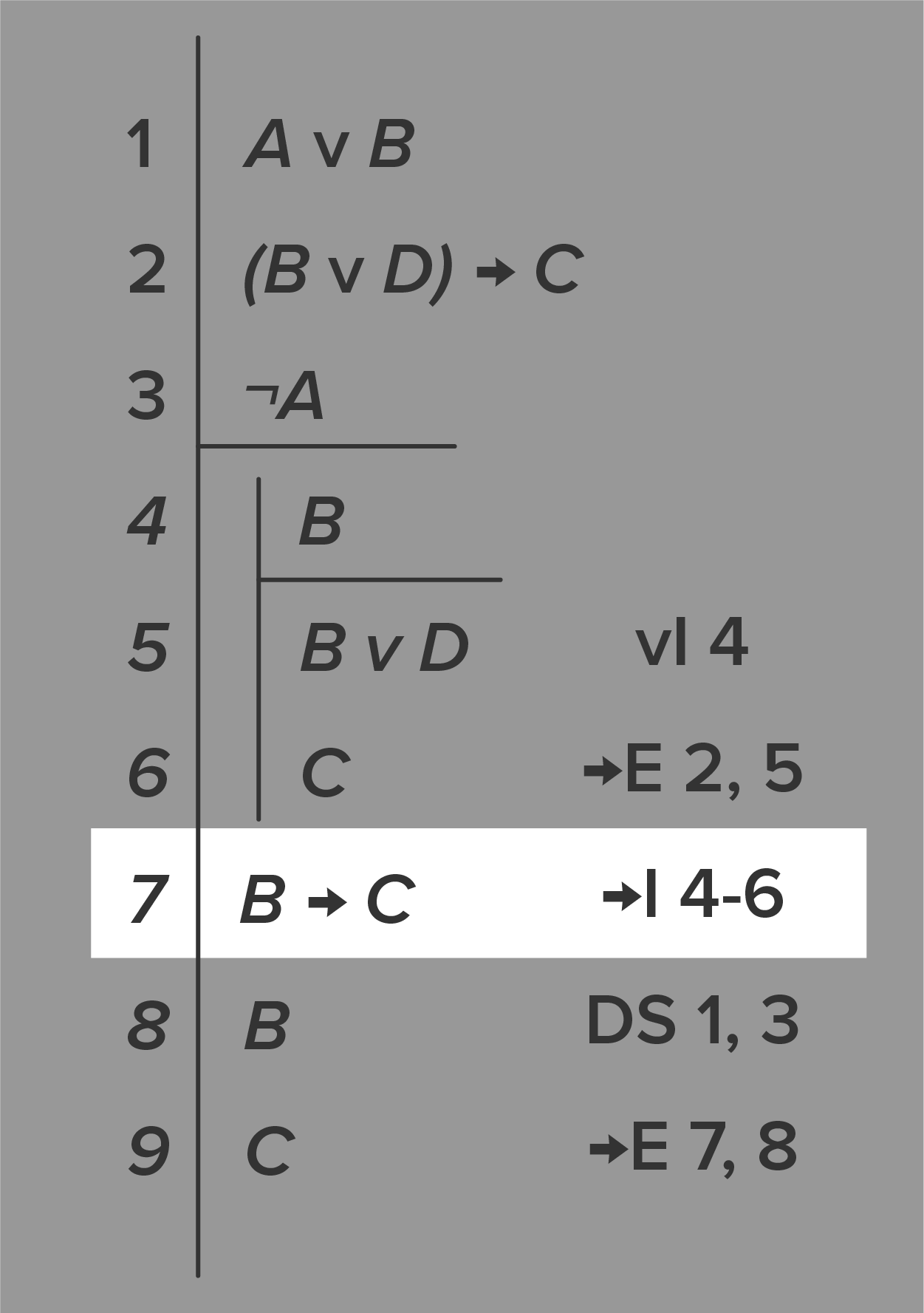

Let’s return to our working example. Note that the subproof is clearly marked and set apart in lines 4-6 from the main proof:

As in the previous proofs, you can see a horizontal line under the subpremise, followed by numbered sentences. You can see the rules and numbers of the previous sentences that make each derivation possible. The additional vertical line helps demarcate the subproof with its subpremise(s). Our subpremise is that B is true, so there is also a new horizontal line underneath line 4. There is no notation on the right for this line, because the truth of B is an assumption, not a derivation of the proof. It is saying, “Let’s see what happens if B is true.” The subsequent lines in the subproof do require notations to show the logical rules that apply and the lines in the proof they apply to.

Notice after we’ve concluded our subproof, the final step is conditionalization in line 7. We resume the main proof with the conditional sentence, If B, then C. This sentence is added to the main proof because it discharges the assumption from our subproof that B is true, but turns it into a sentence that we can use. It states that if B is assumed, then we can derive C, which the subproof has proven.

This represents the natural language statement in that “if Brenda goes, you know there’ll be a computer.” You may see here how the subproof gives us an important shortcut to proving or explaining an argument.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM 1)“INTRODUCTION TO LOGIC AND CRITICAL THINKING” BY MATTHEW J. VAN CLEAVE. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPEN.UMN.EDU/OPENTEXTBOOKS/TEXTBOOKS/457 2) “FORALL X: CALGARY” BY TIM BUTTON. ACCESS FOR FREE AT FORALLX.OPENLOGICPROJECT.ORG. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.