Table of Contents |

After examining aspects of health and wellness on more large-scale levels, such as globally and nationally, these next two lessons will focus on examining your own levels of health and wellness, with the ultimate purpose of selecting a health behavior that you’d like to change or adopt by creating a SMART goal.

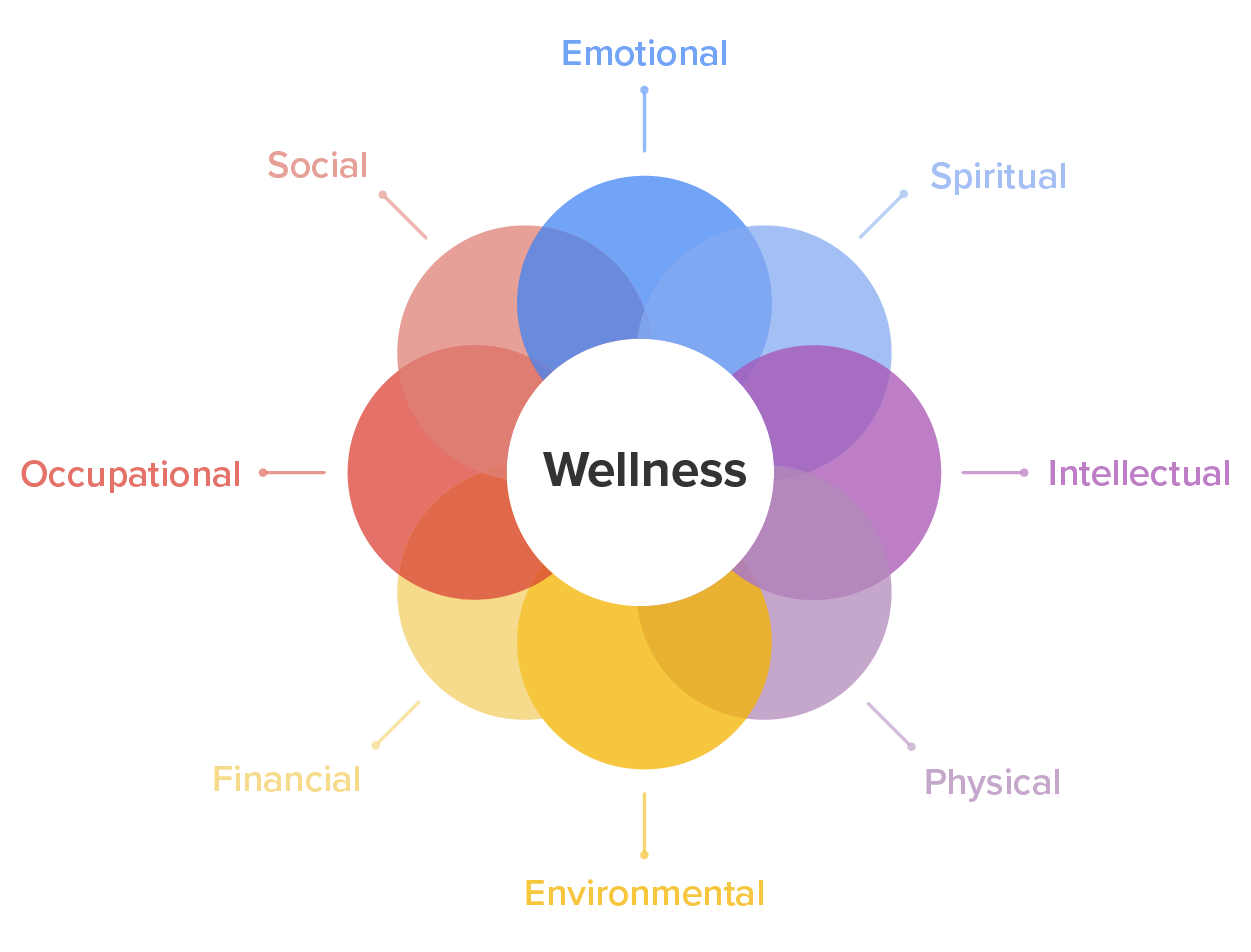

In the lesson, titled “Health and Wellness”, you encountered the eight dimensions of wellness. Consider your current habits and future goals for each dimension with the following questions adapted from a wellness guide from the Department of Health and Human Services (SAMHSA, 2016). Using these questions as a guide to journal or brainstorm on your own is a helpful place to start narrowing down what your SMART goal might cover.

This dimension is about recognizing your body’s habits and needs to stay physically healthy.

This dimension is about dealing with life’s challenges and stressors and managing your emotions and feelings.

This dimension is about keeping our surroundings safe, clean, and pleasant.

This dimension is about the connection, care, and support derived from our positive relationships with other people.

This dimension is about developing and expanding our knowledge, skills, and perspectives.

This dimension is about seeking out responsibilities that give our lives accomplishment and fulfillment while not making us feel like we are taking on too much.

This dimension is about the purpose and meaning we derive from life based on personal beliefs and values.

This dimension is about our level of understanding and satisfaction with our finances.

Life demands, stress, crises, or trauma can impact or alter our routines and habits. This can lead to emotional (anxiety or depression), social (crankiness, isolation, or anger), or physical (tiredness or agitation) imbalances. Establishing new, better habits that support our wellness goals and values can be challenging, but worth it. Developing healthier routines and habits in our lives can lead to positive feelings (emotional); relationship satisfaction (social); increased energy (physical); inspiration (emotional); and the feeling that we are using our creative talents, skills, and abilities to engage in activities (occupational, intellectual, and spiritual).

While working toward every dimension of wellness in one way or another is a great goal for improving the overall quality of life, goal-setting works best when it does not try to take on too many changes at once. Hopefully, your reflection on the questions for each of the eight dimensions of wellness provided some specific ideas on things you can do—at your own pace, in your own time, and within your own abilities.

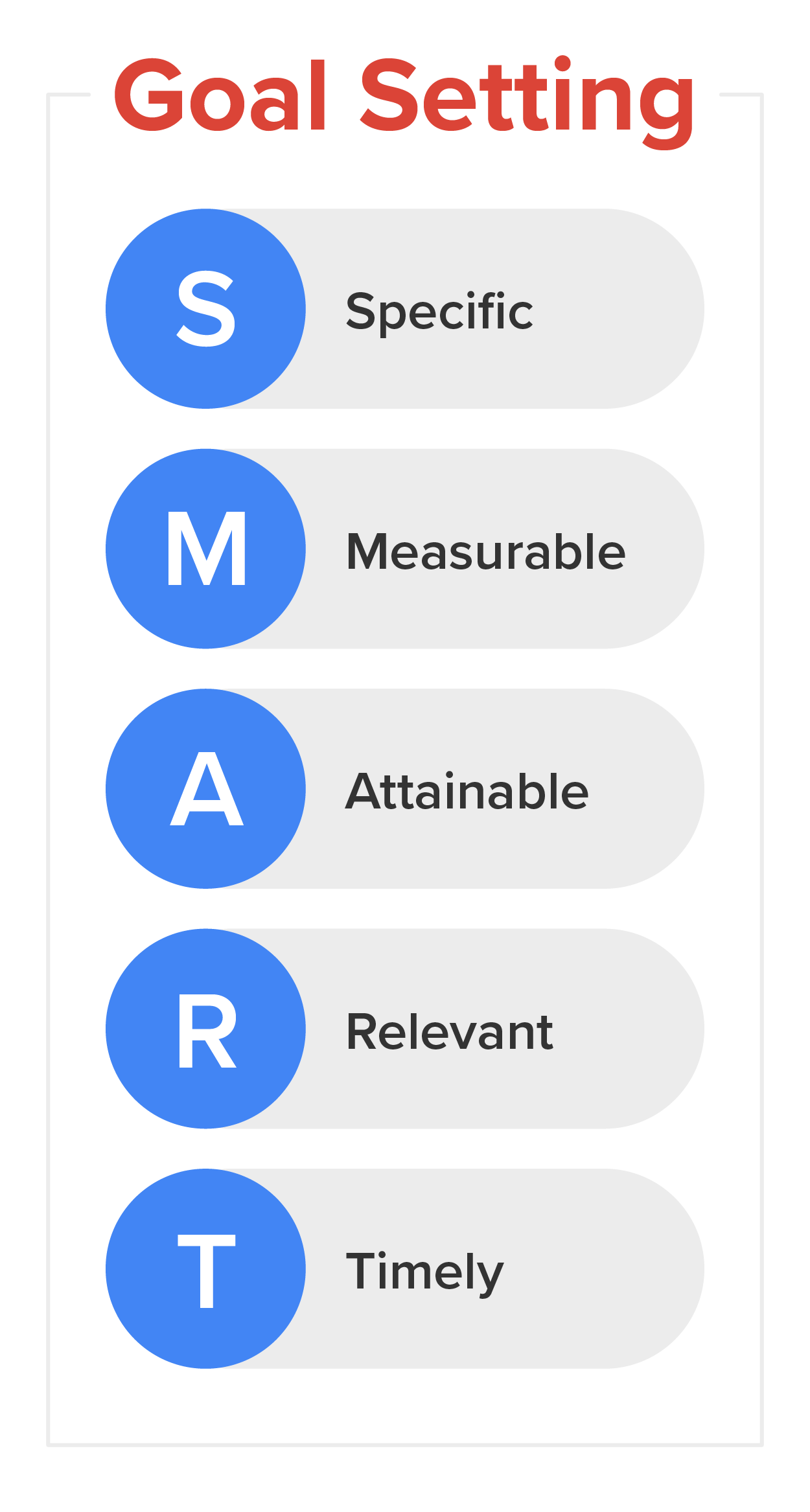

Have you ever said to yourself that you need to “eat healthier” or “exercise more” to improve your overall health? How well did that work for you? In most cases, probably not very well. That’s because these types of statements are too vague and do not give us any direction for what truly needs to be done to achieve such goals. To have a better chance of being successful, the acronym SMART is a useful and well-known framework for setting goals.

Making a goal specific is about ensuring that it has a focused and clear path for what you actually need to do.

EXAMPLE

Do you see how these goal examples are more helpful than just saying you will “eat healthier” or “exercise more”? These goals provide direction regarding what action needs to be taken on a regular basis.

Making a goal measurable enables you to track your progress and ties in with the Specific component. Notice that the aforementioned examples all have actual numbers associated with the behavior change that let you know whether or not it has been met.

In some SMART goal models, you may also see the A standing for Achievable. Having a goal that is Attainable and Achievable means ensuring that the goal is within your capabilities and not too far out of reach. For example, if you have not been physically active for a number of years, it would be highly unlikely that you would be able to achieve the goal of running a marathon within the next month. Weight loss is another common goal area where people may not always be aware of what is achievable or attainable, resulting in goals that are probably out of reach without extreme measures. Someone may set a goal to lose 20 lb (9.1 kg) by the time they have their vacation a month from now, without the knowledge that a safe and sustainable rate of weight loss is about 1–2 lb (0.45–0.91 kg) a week.

IN CONTEXT

One way of looking further at SMART goals is by categorizing a goal as either a product goal or a process goal. Product goals focus only on the end result, which is typically something numerical, and success is defined by reaching that result. Weight loss is a common product goal that people set, where a SMART goal example might be to lose 20 lb (9.1 kg) in the next 3 months. However, because the goal is focused on only the scale’s number, a product goal like this may be less desirable for setting up long-term, positive habits.

Conversely, process goals focus on the journey and the regular consistent actions that are taken. Success is more defined by personal growth and insight over a raw number, which provides a sense of confidence and accomplishment. A weight loss goal could be transformed into a process goal by tracking a behavior like regular exercise.

In sports, winning is an example of a product goal. The numbers that show that someone was the best competitor or beat the other team are the end results. In contrast, process goals in sports might focus on aspects like improving technique or honing strategy through devoted practice over time. One meta-analysis of multiple studies on sports confirmed that process goals had a larger effect on performance than product goals (Williamson et al., 2022).

Realistic qualities describe having a goal that is something you will be able to continue doing and incorporating as part of your regular routine and lifestyle. For example, if you made a goal to kayak twice a week because you love the peaceful feeling of being out on the water, but don’t have the financial resources to purchase or rent a kayak or are not close enough to a body of water for kayaking, then this is not going to be realistic.

Realistic qualities also involve making your goal relatively conservative and forgiving. While it can feel positive to set very ambitious goals and think about how we would be at our best, starting even smaller than you may think is a wise step. It’s much better to build on small successes and gain confidence than to work on your goal for a week and realize it’s not realistic in terms of being sustainable for the long term.

In some SMART goal models, you’ll see the term Relevant. While this can also encompass the goal being realistic, a Relevant goal is based on personal relevance—that it’s important to you and not undertaken because someone else wants you to do it or because you feel a sense of pressure or obligation.

A goal that is Timely, or Time-oriented, has a target date or deadline by which the goal needs to be met. This will keep you on track and motivated to reach the goal while also evaluating your progress. The foundation for large-scale goals is based on small, consistent behaviors or habits. When considering the Timely aspects of goals, habits can take some time to change. A goal where the deadline is just a few weeks away may not truly cement lasting habit formation. However, a goal where the deadline is years away can seem so far in the future that it’s easy to lose interest. A 3–6-month target date often works well as a happy medium.

Understandably, many types of health goals are ones where the ideal is to have them become a regular part of our daily habits and lifestyle. It would be counterproductive to set a 3-month goal for at least 7 hours of sleep each night and then go right back to sporadic sleep hours once the Time-oriented target date is reached. However, all SMART goals do need a Time-oriented aspect as this inspires persistence toward the deadline. Reaching the deadline does not mean stopping the behavior in many cases; rather, it becomes an appropriate time to celebrate progress, reflect on what worked, and perhaps set a new goal if the previous one was reached.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) "WELLNESS" BY EXTENDED LEARNING INSTITUTE (ELI)" AT NOVA. ACCESS FOR FREE AT: oer commons. (2) "HEALTH EDUCATION" BY COLLEGE OF THE CANYONS. ACCESS FOR FREE AT: open.umn.edu. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL..

Disclaimer: The use of any CDC and United States government materials, including any links to the materials on the CDC or government websites, does not imply endorsement by the CDC or the United States government of us, our company, product, facility, service, or enterprise.

REFERENCES

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2016). Creating A Healthier Life: A Step-By-Step Guide To Wellness. Publication ID: SMA16-4958 store.samhsa.gov/product/Creating-a-Healthier-Life/SMA16-4958

Williamson, O., Swann, C., Bennett, K. J., Bird, M. D., Goddard, S. G., Schweickle, M. J., & Jackman, P. C. (2022). The performance and psychological effects of goal setting in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-29. doi.org/10.1080/1750984x.2022.2116723