Table of Contents |

Viruses are acellular and do not have the components to reproduce without the help of a host cell. To make new viruses, they must do the following:

There are some important differences between viral replication in prokaryotic versus eukaryotic cells. This includes the location of nucleic acid replication as summarized in the table below.

| Site of Viral Nucleic Acid Replication | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotic Viruses | Cytoplasm (no nucleus present) | |

| Eukaryotic DNA viruses | Generally the nucleus, with a few exceptions that replicate in the cytoplasm (e.g., poxviruses) | |

| Eukaryotic RNA viruses | Generally the cytoplasm, with a few exceptions (e.g., influenza virus, HIV) | |

Understanding viral methods of replication is important in developing ways to reduce transmission and to treat infection. Because viral replication uses the machinery of the host cell, antiviral medications need to carefully target the parts of the viral life cycle that are unique to the virus. For example, common medications used to treat HIV target enzymes involved in copying viral RNA into DNA, producing proteins, and integrating DNA into the host cell chromosome (Churchill, 2015; Scarsi, 2020). You will learn more about specific medically important viruses, prevention, and treatment in other lessons.

As discussed above, research into bacteriophage life cycles has been important in understanding many aspects of viral reproduction that are relevant for other types of viral infections.

Based on their life cycles, bacteriophages can be classified into two major categories: virulent and temperate phages. Infection by virulent phages typically leads to relatively rapid death of the host cell through cell lysis (bursting open of a cell resulting in cell death and release of its contents). In contrast, temperate phages can become part of the host chromosome and the viral genome is replicated as the host cell reproduces. Eventually, temperate phages can be induced to make newly assembled (progeny) viruses.

This lesson describes the lytic and lysogenic cell cycles in detail, then describes other types of viral infections.

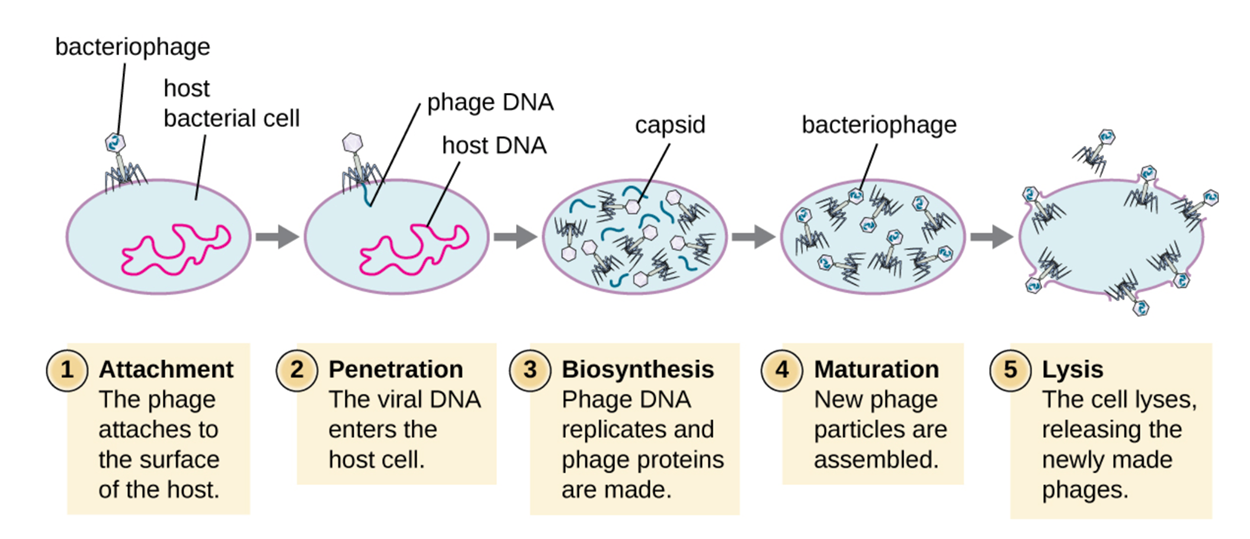

During the lytic cycle of a virulent phage, a bacteriophage injects its genetic material into a bacterial cell and the bacterium immediately begins to produce new phages. The cycle ends when the bacterium lyses to release the progeny viruses. The five major stages of the cycle are as follows (also summarized in the image below).

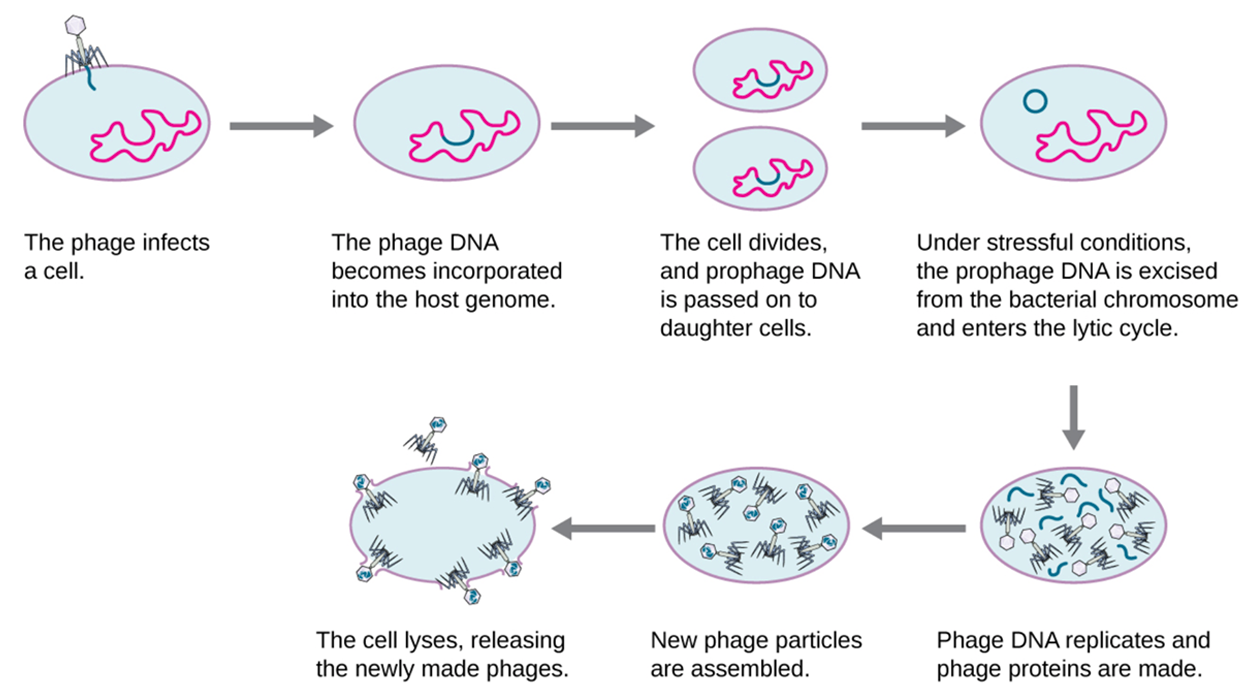

Lysogeny is the process by which a bacterium is infected by a temperate phage that enters the lysogenic cycle.

This cycle begins similarly to the lytic cycle. First, the phage must attach to a cell and inject its genetic material (penetration). However, the process differs once the bacteriophage genome is inside the bacterial cell. At this point, the genome can be integrated into the host cell chromosome.

After integration has occurred, the viral genome is called a prophage and the infected bacterial cell is called a lysogen.

As the bacterial cell replicates, it duplicates copies of its chromosome that contain the prophage. Therefore, it produces daughter cells that are also lysogens.

The prophage may be latent or inactive within the cell. However, the presence of the phage may alter the phenotype of the bacterium when its genes are expressed. This change in the host phenotype is called lysogenic conversion or phage conversion.

Some medically important bacteria, such as Vibrio cholerae and Clostridium botulinum, are less virulent in the absence of a specfic prophage. The prophage contains a gene that instructs the bacterial cell to produce a toxin which causes the infected bacterial cells to cause illness. As a result of phage infection, V. cholerae produces a toxin that can cause severe diarrhea, and C. botulinum produces a toxin that can cause paralysis

Under certain conditions, such as a changing environment or exposure to an antibiotic, induction can occur (Sutcliffe et al., 2021). In this process, the viral genome can be excised from the host chromosome. At this point, the temperate phage can proceed through a lytic cycle and then infect new host cells. The major stages of the cycle are as follows (also summarized in the image below).

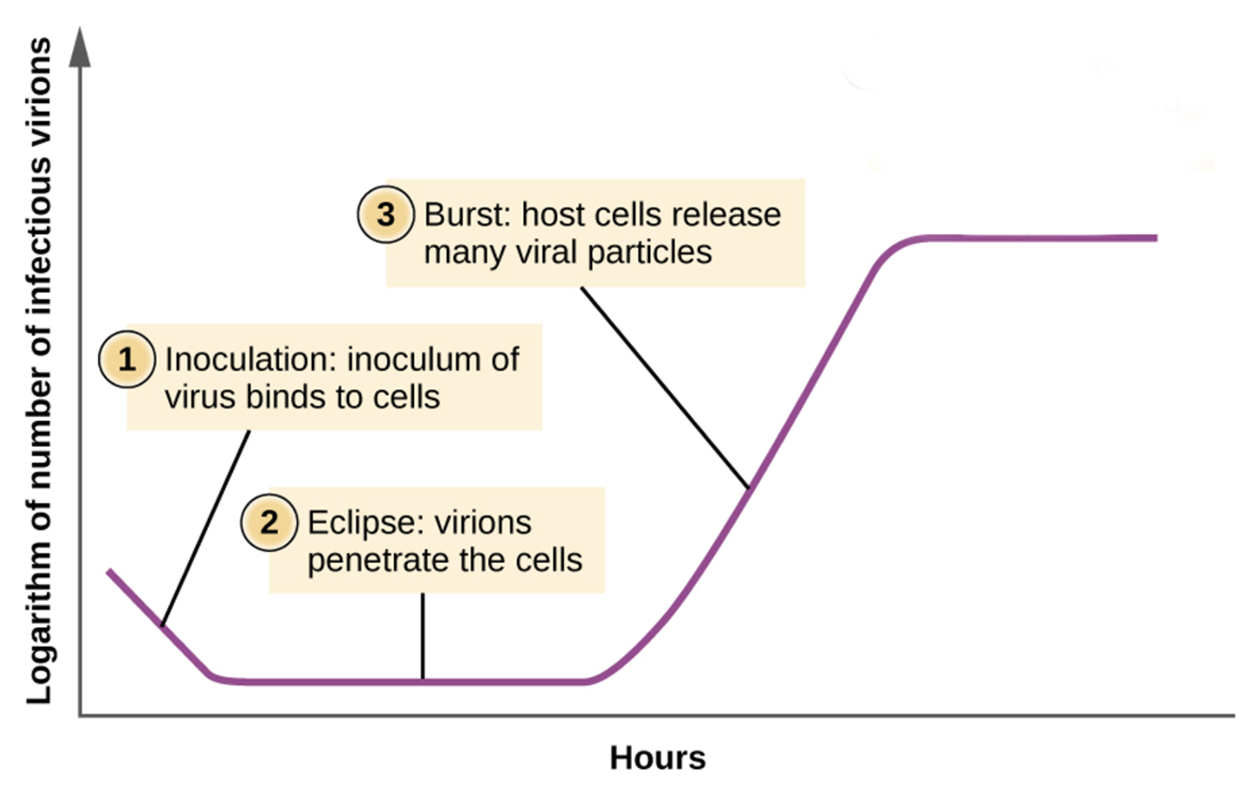

Understanding the lytic life cycle is helpful in understanding the viral growth curve. This is the pattern of growth that appears when the logarithm of the number of infectious virions is plotted over time. The steps of the viral growth curve are stated below and summarized in the image below. There is a period of time during which no infectious virions (virus particles) are present, then there is a rapid increase in the number of infectious virions during the burst phase that occurs when infected cells undergo lysis.

Burst size refers to the number of virions released per bacterium. In contrast, viral titer is the number of virions per unit volume of solution. Unlike bacterial growth curves, viral growth curves show a sudden increase in number of viral particles associated with cell lysis. If no viable host cells remain, then the viral particles begin to degrade during the decline of the culture.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Choudhury, S., Baker, M. R., Chatterjee, S., & Kumar, H. (2021). Botulinum Toxin: An Update on Pharmacology and Newer Products in Development. Toxins, 13(1), 58. doi.org/10.3390/toxins13010058

Churchill, D., Waters, L., Ahmed, N., Angus, B., Boffito, M., Bower, M., Dunn, D., Edwards, S., Emerson, C., Fidler, S., Fisher, M., Horne, R., Khoo, S., Leen, C., Mackie, N., Marshall, N., Monteiro, F., Nelson, M., Orkin, C., Palfreeman, A., … Winston, A. (2016). British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015. HIV medicine, 17 Suppl 4, s2–s104. doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12426

D'Mello-Guyett, L., Gallandat, K., Van den Bergh, R., Taylor, D., Bulit, G., Legros, D., Maes, P., Checchi, F., & Cumming, O. (2020). Prevention and control of cholera with household and community water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions: A scoping review of current international guidelines. PloS one, 15(1), e0226549. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226549

Parker, N., Schneegurt, M., Thi Tu, A.-H., Lister, P., & Forster, B. (2016). Microbiology. OpenStax. Access for free at openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction

Scarsi, K. K., Havens, J. P., Podany, A. T., Avedissian, S. N., & Fletcher, C. V. (2020). HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors: A Comparative Review of Efficacy and Safety. Drugs, 80(16), 1649–1676. doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01379-9

Sutcliffe, S. G., Shamash, M., Hynes, A. P., & Maurice, C. F. (2021). Common Oral Medications Lead to Prophage Induction in Bacterial Isolates from the Human Gut. Viruses, 13(3), 455. doi.org/10.3390/v13030455