Table of Contents |

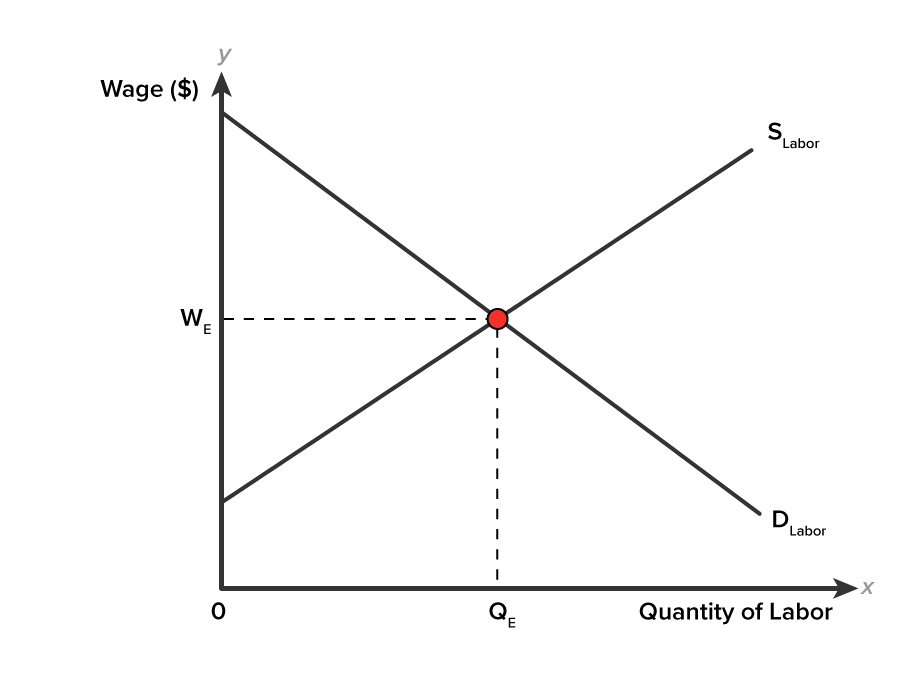

A competitive labor market is one where there are many potential employers for a given type of work, for example, driving a school bus or working in sales at a department store.

In a perfectly competitive labor market firms can hire all the workers they wish at the going market wage, the market’s equilibrium price ( ). Individuals who want jobs at the going market wage will have jobs (

). Individuals who want jobs at the going market wage will have jobs ( ). Neither buyers or sellers of labor can influence the market outcome, because both parties lack market power.

). Neither buyers or sellers of labor can influence the market outcome, because both parties lack market power.

The interaction of supply and demand curves determine the going wage rate ( ) for workers for a particular job type, such as appliance installers or administrative support personnel, and the number of workers hired (

) for workers for a particular job type, such as appliance installers or administrative support personnel, and the number of workers hired ( ).

).

Changes in non-wage factors affect demand for workers. For example, the use of physical capital equipment, which increases worker productivity, shifts the labor demand curve. Changes in non-wage factors affect the supply of workers. For example, changes in worker preferences for certain jobs, such as office work over jobs requiring heavy lifting, shifts the labor supply curve.

When a curve(s) shift, market equilibrium still occurs at the intersection of supply and demand curves.

In contrast to competitive markets, imperfectly competitive labor markets may not have many potential employers for a given worker, or not many potential workers for a given employer. When this happens, market power (the ability to influence price and quantity outcomes) exists.

There are two sources of market power in imperfectly competitive labor markets:

One example of monopsony is the sole coal company in a West Virginia town. If coal miners want to work, they must accept what the coal company is paying. Another example is a town with only one hospital. If skilled surgical nurses want a job at the hospital, they have little choice.

On the supply side of the labor market, workers can collectively organize. A union is an organization that represents the interests of a group of workers. As a single seller of labor, a union operates like a monopoly in the labor market, pushing the wage rate above its competitive level.

What happens when there is market power on both sides of the labor market, in other words, when a union meets a monopsony? Economists call such a situation a bilateral monopoly. Market outcomes will depend on the bargaining power and willingness of the two sides to work together.

We will examine each source of market power to determine how imperfectly competitive labor markets determine outcomes, and how the outcomes differ from competitive labor markets.

Every labor market is unique, and each has a different balance of power between the employer and the employees, except in perfectly competitive markets. In a perfectly competitive labor market, neither buyers nor sellers of labor can influence the market outcome, because both parties lack market power. In imperfectly competitive labor markets, market power can be exercised by employers demanding labor or employees supplying labor.

To protect workers and balance the power relationship between workers and employers in the labor market, the U.S. government has passed a number of labor laws. The following table outlines various labor laws and the issues they address. Many of the laws listed below were only the start of labor market regulations in these areas, and have been followed by related laws, regulations, and court rulings.

| Prominent U.S. Workplace Protection Laws | |

|---|---|

| National Labor Management Relations Act (1935) |

✔ Created procedures for establishing a union that firms are obligated to follow. ✔ Established the National Labor Relations Board for deciding labor disputes. |

| Social Security Act (1935) | ✔ Established a state-run system of unemployment insurance. Eligible workers pay into a fund when employed and receive benefits for a time when unemployed. |

| Fair Labor Standards Act (1938) |

✔ Established a minimum wage. ✔ Placed limits on child labor. ✔ Established rules requiring payment of overtime pay for those in jobs that are paid by the hour and exceed 40 hours per week. |

| Taft-Hartley Act (1947) | ✔ Allows states to decide whether all workers at a firm can be required to join a union as a condition of employment. |

| Civil Rights Act (1964) | ✔ Prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of race, gender, national origin, religion, or sexual orientation. |

| Occupational Health and Safety Act (1970) | ✔ Created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which protects workers from harm in the workplace. |

| Retirement and Income Security Act (1974) | ✔ Regulates employee pension rules and benefits. |

| Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978) | ✔ Prohibits discrimination against people in the workplace who are planning to get pregnant or return to work after pregnancy. |

| Immigration Reform and Control Act (1986) |

✔ Prohibits hiring of illegal immigrants and protects the rights of legal immigrants. ✔ Requires employers to ask for proof of citizenship. |

| Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (1988) | ✔ Requires employers with more than 100 employees to provide written notice 60 days before plant closings or large layoffs. |

| Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) |

✔ Prohibits discrimination against those with disabilities. ✔ Requires reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities on the job. |

| Family and Medical Leave Act (1993) | ✔ Allows employees to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave per year for family reasons, including birth or family illness. |

| Pension Protection Act (2006) | ✔ Penalizes firms for underfunding their pension plans and gives employees more information about their pension accounts. |

| Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (2009) | ✔ Restores protection for pay discrimination claims on the basis of sex, race, national origin, age, religion, or disability. |

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-2e/pages/1-introduction. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.