Table of Contents |

Arguments with categorical sentences cannot be tested for validity in propositional logic. However, they can be tested using Venn diagrams and categorical logic.

First, let’s review the four categorical sentence forms in Venn diagram form.

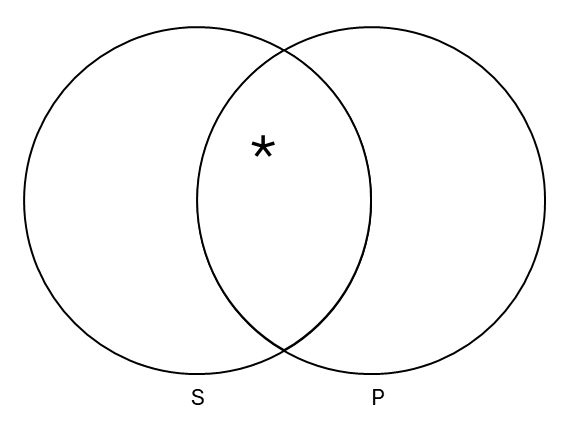

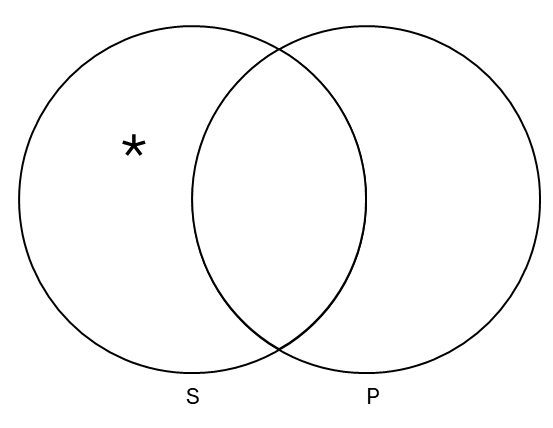

| Some S are P | Some S are not P |

|---|---|

|

|

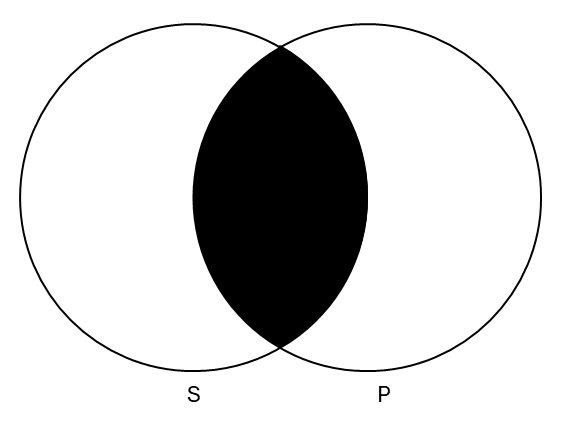

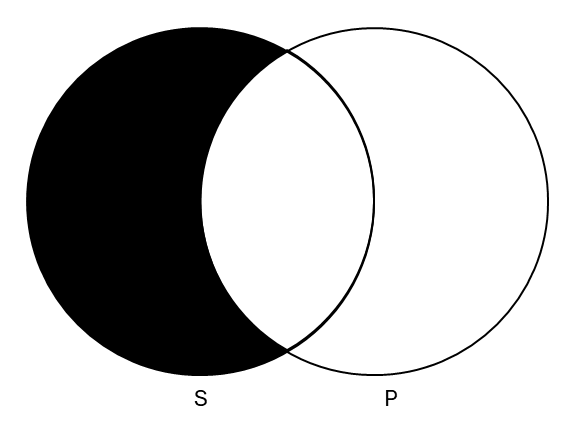

| No S are P | All S are P |

|

|

Now, let’s check the validity of a simple argument with one premise and one conclusion:

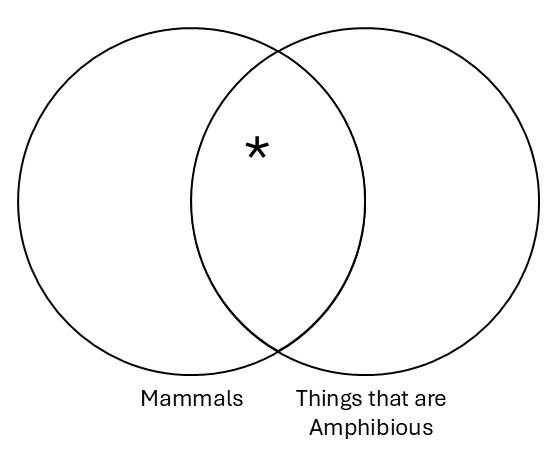

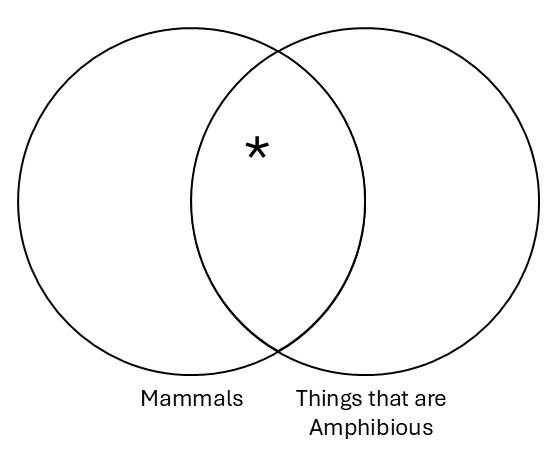

| Some Mammals are Amphibious | Some Amphibious Things are Mammals |

|---|---|

|

|

This argument passes the Venn test of validity because the conclusion Venn contains no additional information that is not already contained in the premise Venn. Thus, this argument is valid.

Let’s now turn to an example of an invalid argument.

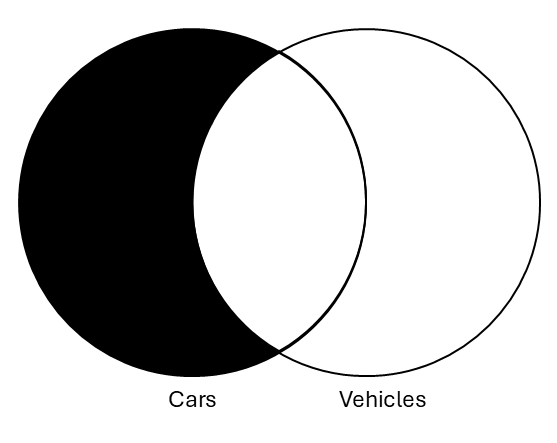

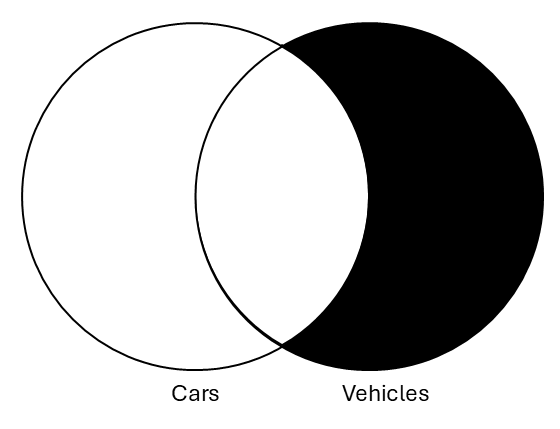

| All cars are vehicles | All vehicles are cars |

|---|---|

|

] ]

|

In this case, the diagrams contain different information. More importantly, we can see that the conclusion (on the right) contains distinctly novel information from the premise diagram. The conclusion asserts that there cannot be anything in the “vehicle” category that isn’t also in the “car” category. However, this information isn’t in the premise, which says that there isn’t anything in the “car” category that isn’t also in the “vehicle” category. Thus, this argument fails the Venn test of validity since there is information in the conclusion that is not in the premise. This argument is invalid.

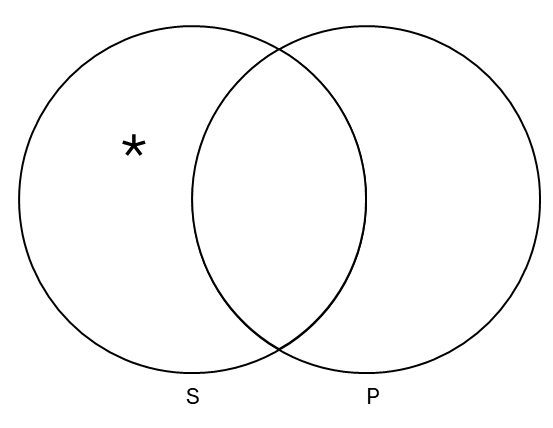

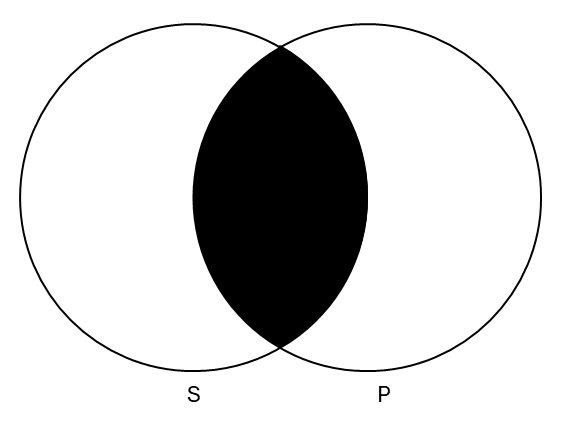

The Venn test of validity is a formal method like proofs and truth tables in sentential logic because we can apply it based on the categorical sentence form alone, without knowing what the categorical variables represent. We can simply use “S” and “P” to represent any subject and predicate category, respectively.

For example:

| Some S are not P | Therefore, no P are S |

|---|---|

|

|

The conclusion (on the right) contains information that is not contained in the premise (on the left). The conclusion explicitly rules out that there is anything that is both in S and in P. In contrast, the premise says nothing about the possibility of things being both S and P. Thus, we can say that this argument fails the Venn test of validity and is invalid because the conclusion introduces the removal of a possibility. We know this even though we have no idea what the categories S and P are. This is the mark of a formal method of evaluation.

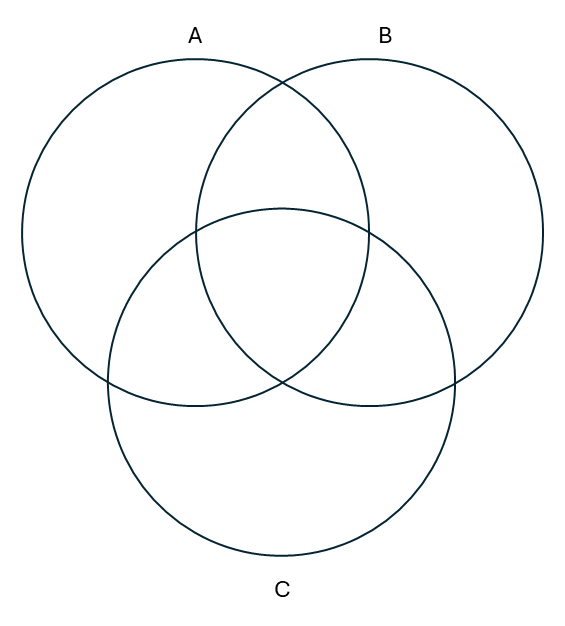

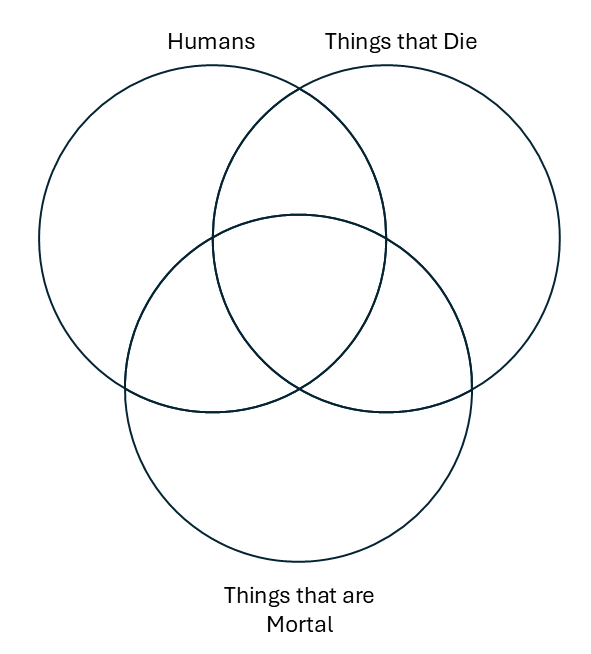

So far, we have been looking at Venn diagrams with two categories. We now turn to Venn diagrams with three. The interpretation of these diagrams is the same as before, with each circle representing a category of things, and the intersections of all three circles representing the things that belong to all three categories.

As you can see from the diagram below, with three circles, we have eight different regions. The eighth region is the one outside the circles. This is the set of presumed things that belong to none of the categories identified. Though in abstraction this concept might be difficult, think about it in concrete terms. If our three categories are “things that fly”, “reptiles,” and “mammals,” a guitar is an object that exists but isn’t in one of these three categories.

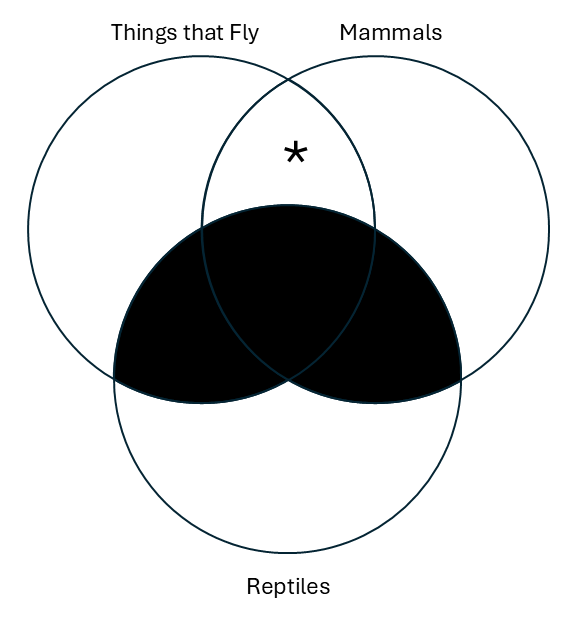

Here is an illustration of a three-circle diagram. In this example, we are not working from premises and a conclusion, simply showing the relationships between real-world categories.

You can see from the intersection of categories A and B that there is at least one thing that can fly and is a mammal (a bat). However, the intersection of categories B and C show there is no thing that can fly and is a reptile (at least not currently alive). Moreover, there is no thing that is a reptile and a mammal. (Apologies to any lizard people taking this class!)

Note that if any intersection of two categories is shaded, the center must also be shaded. Because if something isn’t B and C, then it’s definitely not B, C, and A. If nothing is a reptile and a mammal, it can’t also be a flying reptile and mammal.

Recall that syllogism is an argument where the conclusion follows from two premises; a categorical syllogism is syllogism involving at most three categories. As we have seen, there are four different forms of categorical sentences:

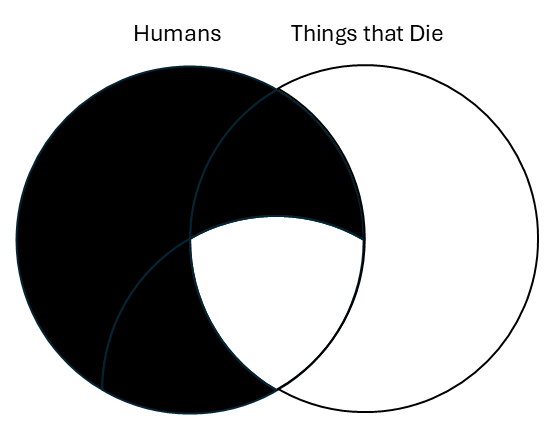

The next thing we need to do is represent the information from the two premises in our three-category Venn. We'll start with the first premise, which says, “All humans are things that are mortal.”

The next thing we have to do is fill in the information for the second premise, “All things that are mortal are things that die.”

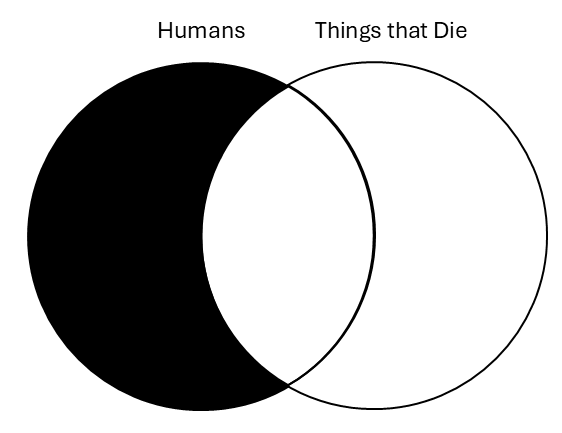

The next thing we have to do is construct a two-category Venn for the conclusion. The conclusion states there is nothing in the “humans” category that isn’t also in the “things that die” category. It also allows that there are things that die, but that aren’t humans. Last, we compare this to the three-category Venn (or premises Venn) to see if they are the same.

| Premises Venn | Conclusion Venn |

|---|---|

|

|

The relevant points of comparison are the “humans” and “things that die” categories. Do the two circles have the same shading? They do not. In the premises Venn, part of the intersection between the two is shaded; but in the conclusion Venn, the intersection is not shaded. Since they do not look exactly alike, we must ask whether the conclusion Venn contains more information than the premise Venn. In the premise Venn, every part of the “humans” category that is outside the “things that die” category is shaded. The conclusion Venn only rules out humans that don’t die. The premise Venn rules out the same (in fact, more) possibilities as the conclusion Venn; the conclusion thus doesn’t contain more information than the premises. Thus, this argument passes the Venn test of validity.

Note that it doesn’t matter that the premise Venn contains more information than the conclusion Venn. That is to be expected, since the premise Venn represents a whole other category that the conclusion Venn isn’t. This is allowable. What isn’t allowable (and thus would make an argument fail the Venn test of validity) is if the conclusion Venn contained information that wasn’t already contained in the premise Venn.

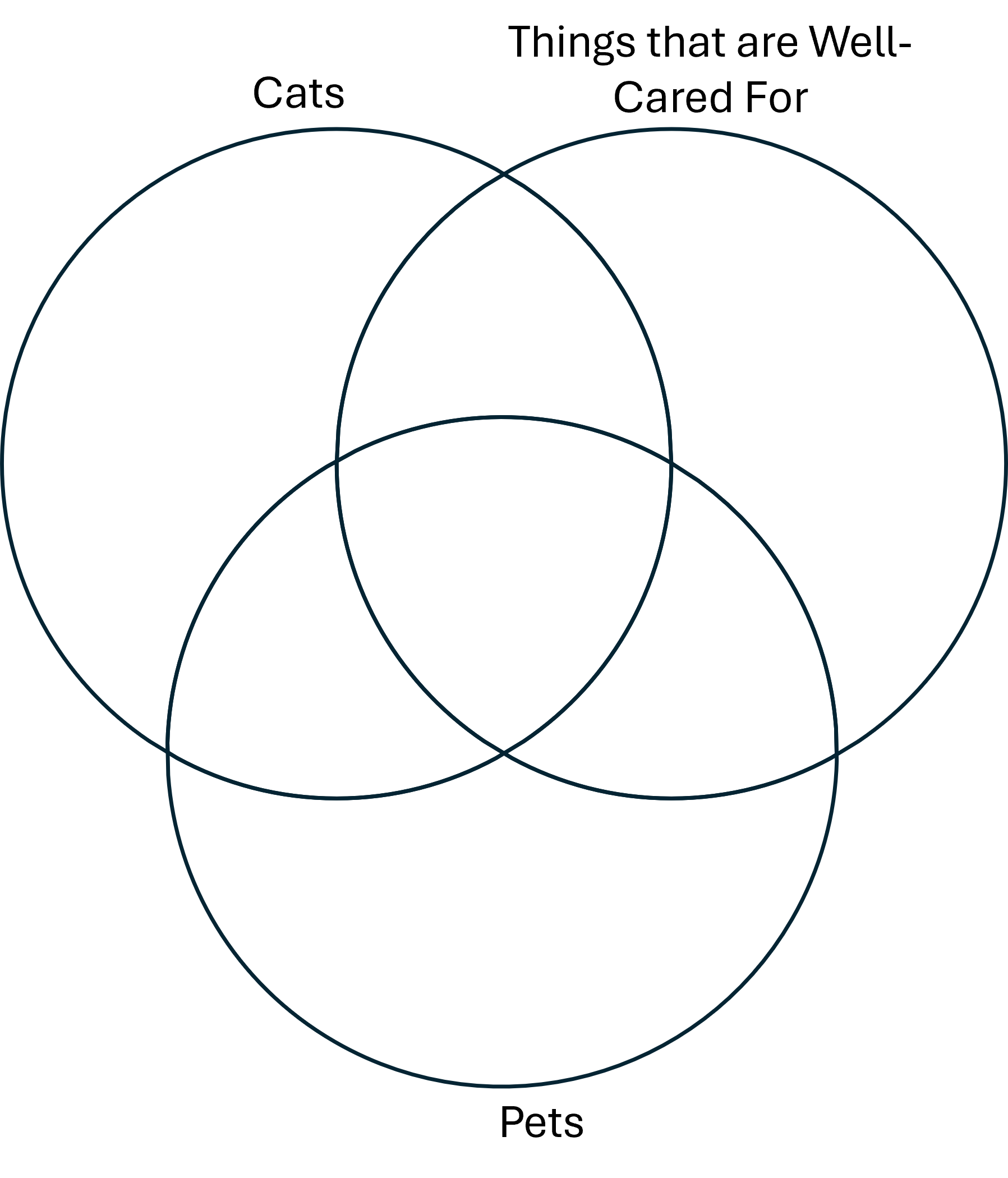

Let’s look at one more example of a three-category argument.

In the problem above, we were able to quickly clear this up by first shading for the universal sentence, but here we do not have a universal. The next premise here presents the same dilemma. We have to represent that there is at least one thing that is both a bear and a mammal, but is it also two-legged? Unfortunately, we have also reached the end of our premises, so there will be no more information to guide us.

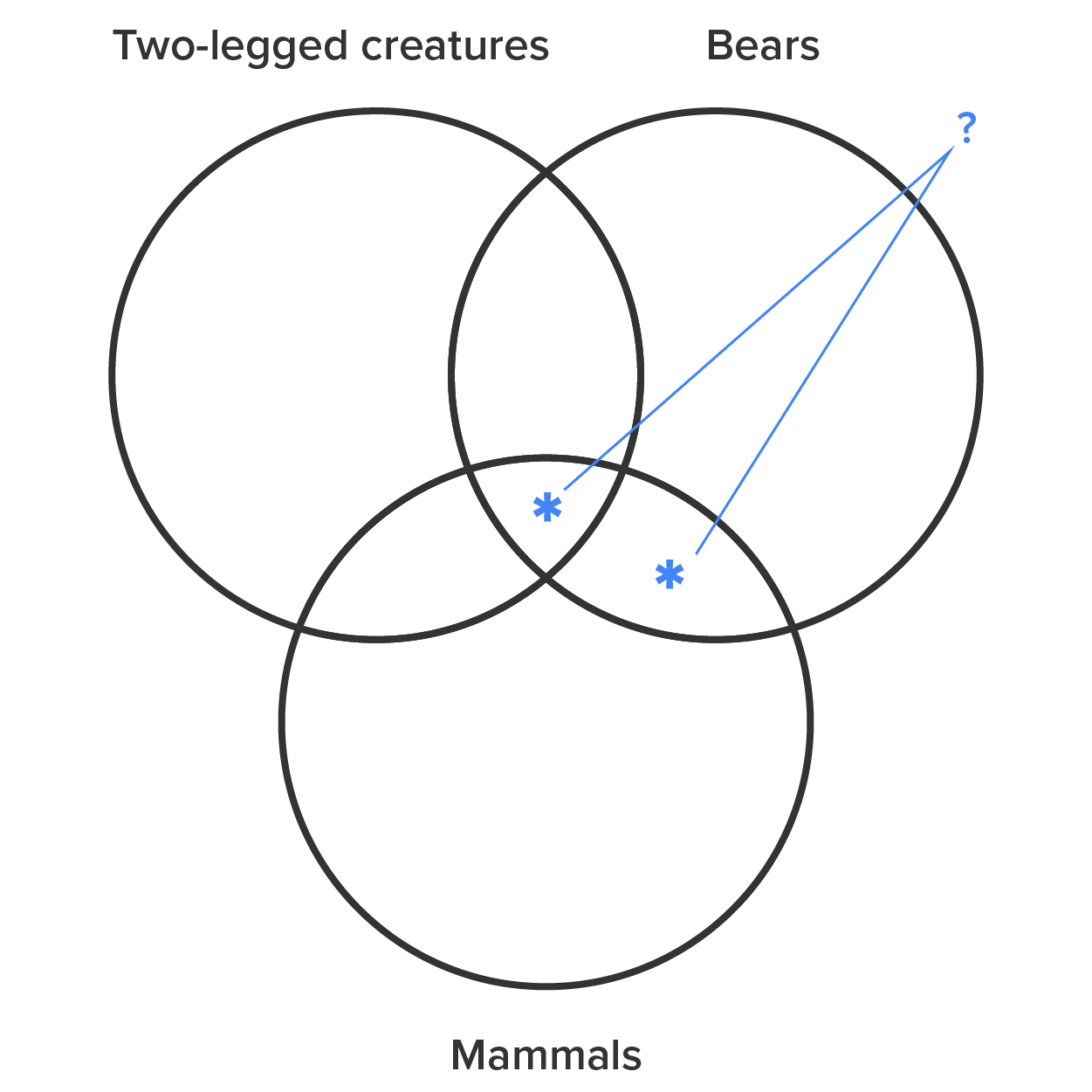

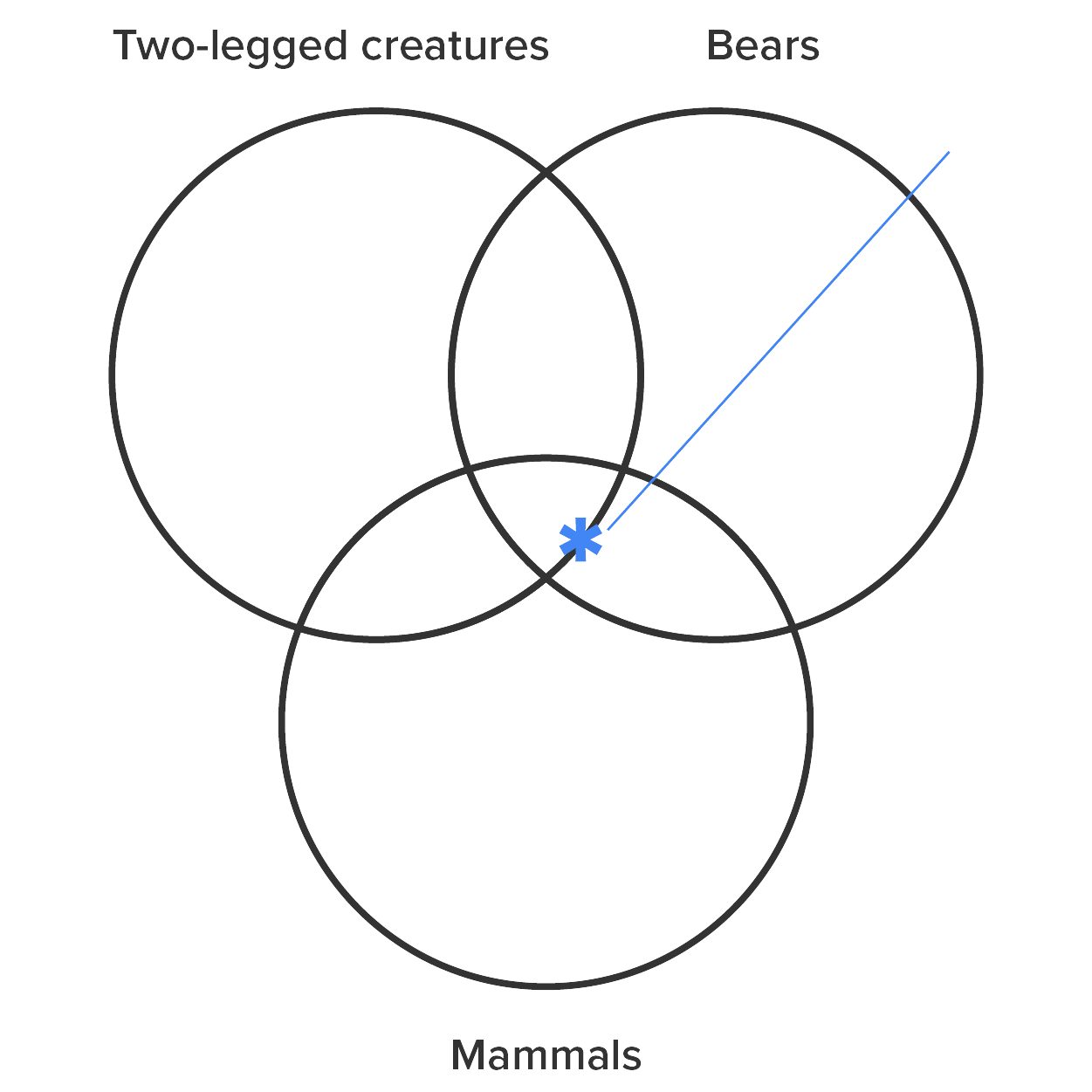

Thus, in order to accurately represent the information contained in this premise, we must adopt a new convention. That convention says that when we encounter a situation where we must represent a particular between two categories on a three-category Venn and don’t know whether the particular also belongs in the third category, then we must put the asterisk on the line in between the two areas in which it might belong. This is what the Venn diagram will look like when we have noted there is at least one bear that is a mammal that may or may not be two-legged.

We must do this same thing for the second premise since we encounter the same problem. We know there is at least one two-legged mammal, but do not know from the premises if it is or is not a bear. So once again we place the asterisk on the border between the two possibilities.

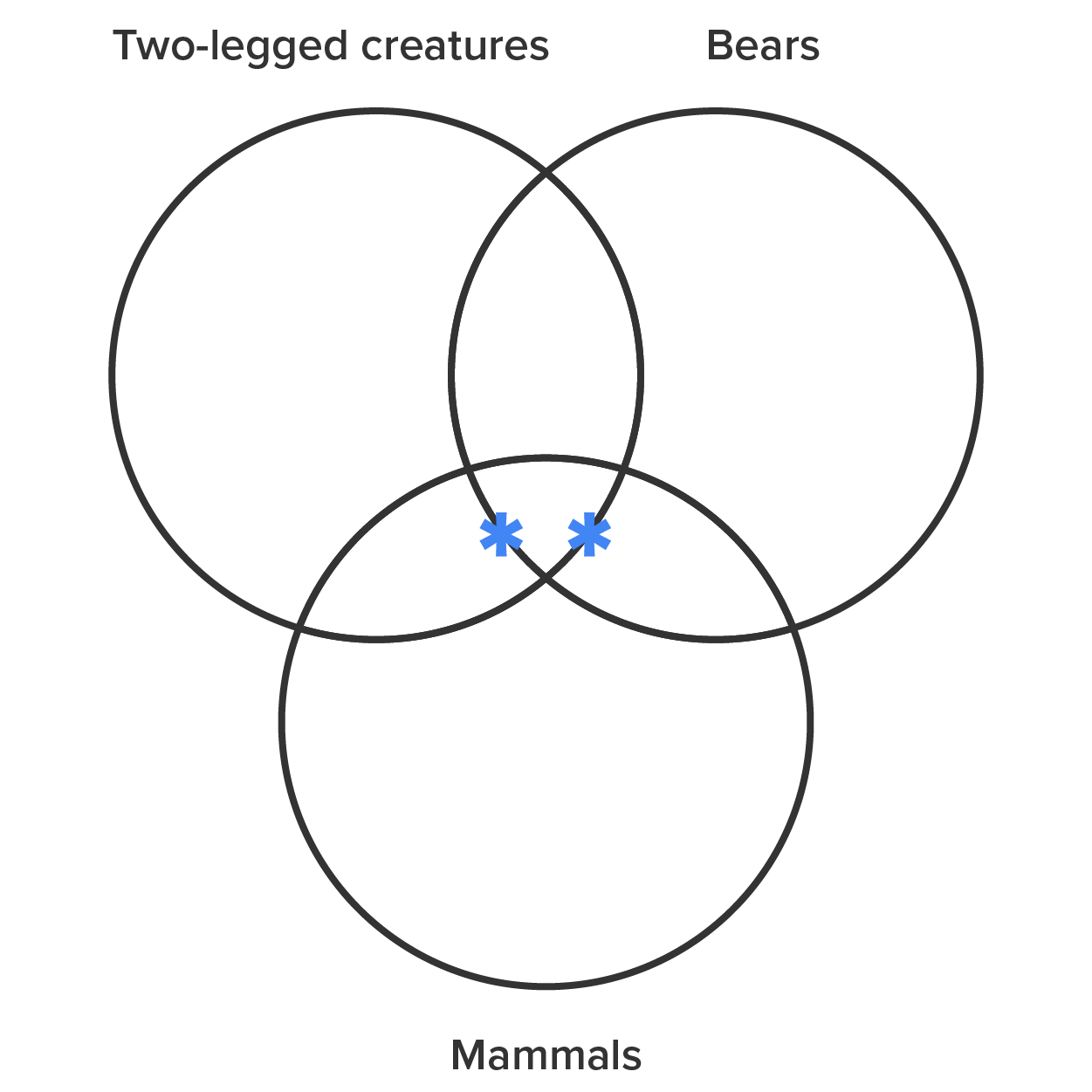

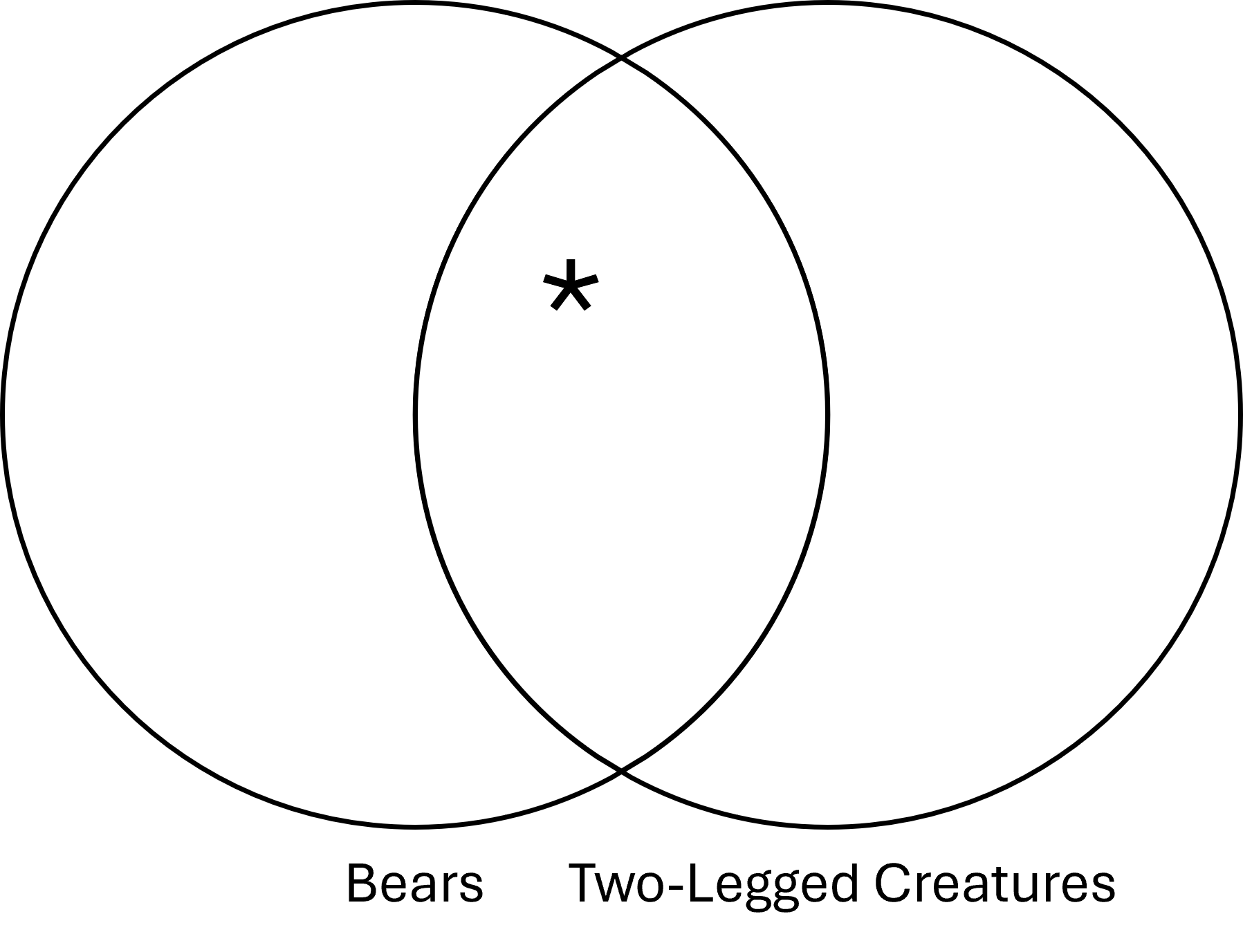

We can draw no more conclusions from these premises, so let’s diagram the conclusion, which states that some two-legged creatures are bears.

We can see that this argument fails the Venn test of validity because the conclusion contains information not in the premises. The conclusion asserts that there is at least one thing that is both a two-legged creature and a bear, while the premises Venn contains no such information.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM “INTRODUCTION TO LOGIC AND CRITICAL THINKING” BY MATTHEW J. VAN CLEAVE. ACCESS FOR FREE AT open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/457. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.