Table of Contents |

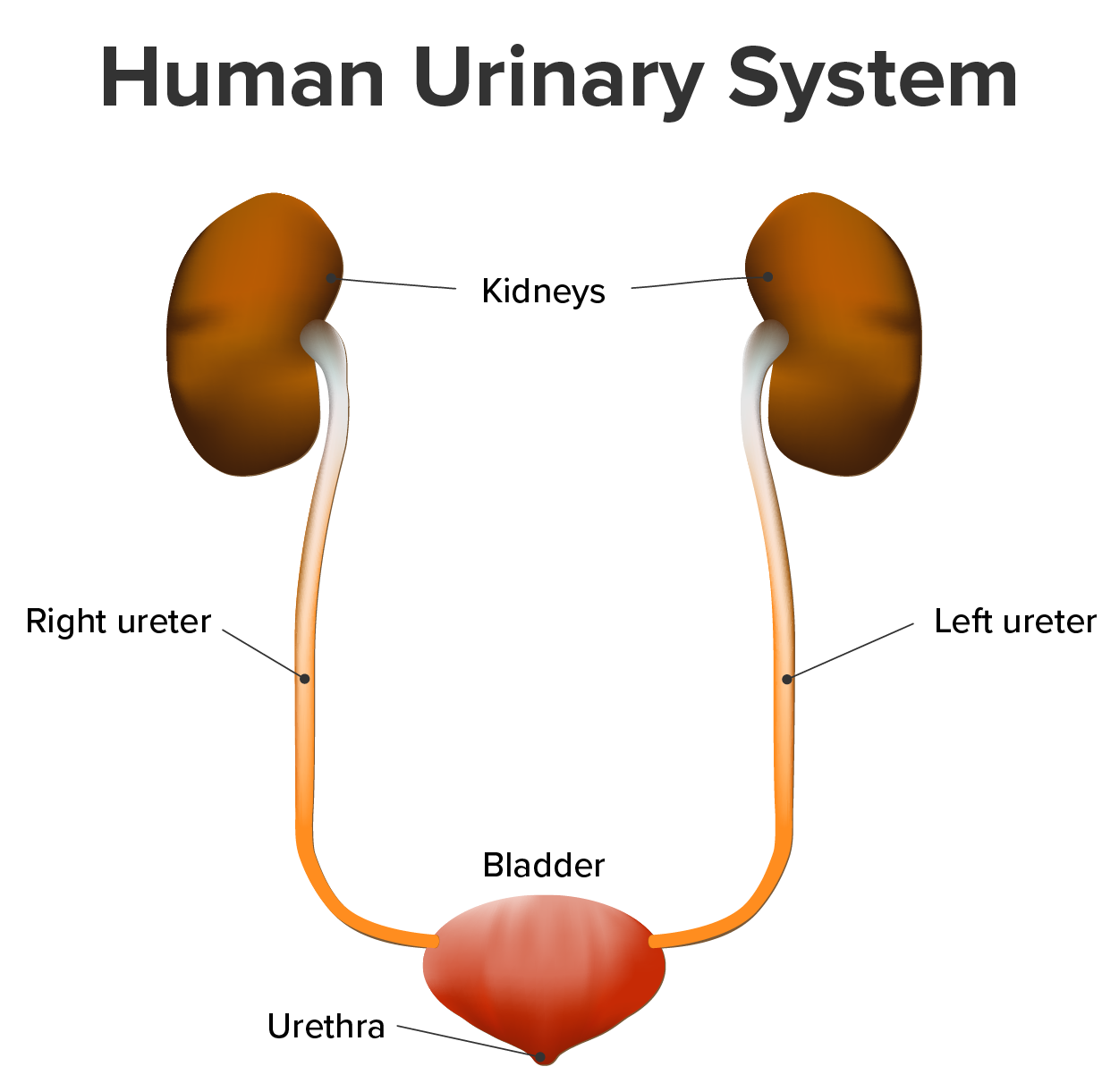

The urinary system (shown below) has roles you may be well aware of—cleansing the blood and ridding the body of wastes probably come to mind.

However, there are additional and equally important functions played by the system. Take, for example, the regulation of pH, a function shared with the lungs and the buffers in the blood (recall that a buffer is a solution that resists a change in pH by absorbing or releasing hydrogen or hydroxide ions). Additionally, the regulation of blood pressure is a role shared with the heart and blood vessels. What about regulating the concentration of solutes in the blood and the concentration of red blood cells? Approximately 85% of the erythropoietin (EPO) produced to stimulate red blood cell production is produced in the kidneys. The kidneys also perform the final synthesis step of vitamin D production, converting calcidiol to calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D.

Each of these functions is vital to your well-being and survival. The urinary system, controlled by the nervous system, also stores urine until a convenient time for disposal and then provides the anatomical structures to transport this waste liquid to the outside of the body. Failure of nervous control or the anatomical structures leading to a loss of control of urination results in a condition called incontinence, in which there is involuntary loss of bladder control.

This challenge will help you to understand the urinary system and how it enables various functions critical to human survival. It is best to think of the kidney as a regulator of plasma makeup rather than simply a urine producer.

The urinary system’s ability to filter the blood resides in about 2 to 3 million tufts of specialized capillaries—the glomeruli—distributed more or less equally between the two kidneys. Because the glomeruli filter the blood based mostly on particle size, large elements like blood cells, platelets, antibodies, and albumen (and other proteins in the blood) are excluded.

The glomerulus is the first part of the nephron, the functional unit of the kidney that then continues as a highly specialized tubular structure responsible for creating the final urine composition. All other solutes, such as ions, amino acids, vitamins, and wastes, are filtered to create a filtrate composition very similar to plasma. The glomeruli create about 200 liters (189 quarts) of this filtrate every day, yet you excrete less than two liters of waste called urine.

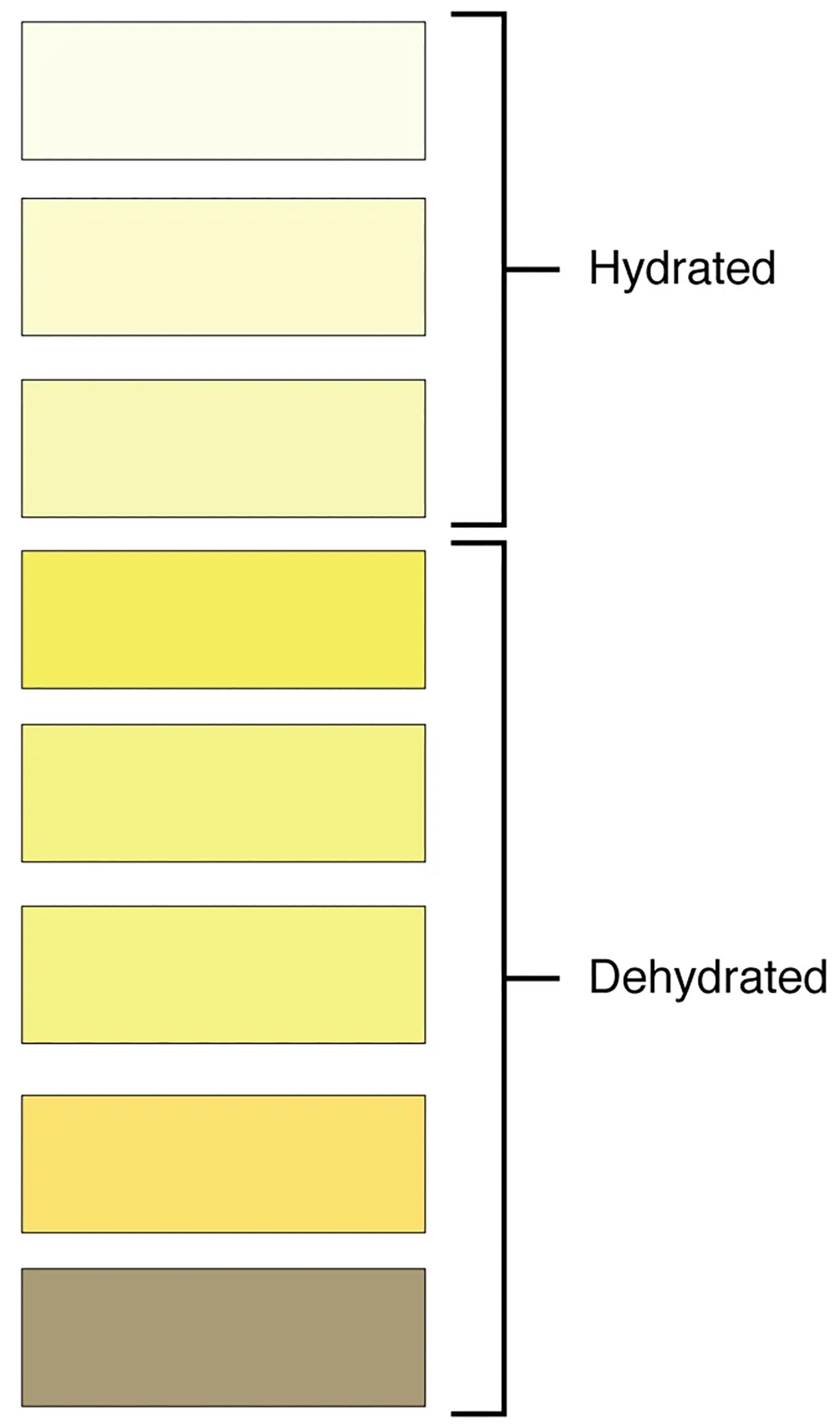

Characteristics of the urine you excrete change depending on influences such as water intake, exercise, environmental temperature, nutrient intake, and other factors (see the table below). Some of the characteristics such as color and odor are rough descriptors of the state of hydration (whether you are hydrated or dehydrated).

EXAMPLE

If you exercise or work outside and sweat a great deal, your urine will turn darker and produce a slight odor, even if you drink plenty of water.| Normal Urine Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | Normal values |

| Color | Pale yellow to deep amber |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Volume | 750–2000 mL/24 hour |

| pH | 4.5–8.0 |

| Specific gravity | 1.003–1.032 |

| Osmolarity | 40–1350 mOsmol/kg |

| Urobilinogen | 0.2–1.0 mg/100 mL |

| White blood cells | 0–2 HPF (per high-power field of a microscope) |

| Leukocyte esterase | None |

| Protein | None or trace |

| Bilirubin | <0.3 mg/100 mL |

| Ketones | None |

| Nitrites | None |

| Blood | None |

| Glucose | None |

Urinalysis (urine analysis) often provides clues regarding renal disease. Normally, only traces of protein are found in urine, and when higher amounts are found, damage to the glomeruli is the likely cause.

Both urea and uric acid are measured in urine analysis. High levels of uric acid can indicate conditions such as gout or kidney stones, whereas high levels of urea nitrogen can indicate issues such as kidney injury or disease, dehydration, increased protein breakdown, or too much protein in an individual’s diet.

Additionally, unusually large quantities of urine may point to diseases like diabetes mellitus or hypothalamic tumors that cause diabetes insipidus.

The color of urine is determined mostly by the breakdown products of red blood cell destruction (see the image below). The “heme” of hemoglobin is converted by the liver into water-soluble forms that can be excreted into the bile and indirectly into the urine. The characteristic yellow pigment of urine is called urochrome.

Urine color can be affected by certain foods like beets, berries, and fava beans. However, a kidney stone or a cancer of the urinary system may produce sufficient bleeding to manifest as pink or even bright red urine. Diseases of the liver or obstructions of bile drainage from the liver impart a dark “tea” or “cola” hue to the urine.

Dehydration produces darker, concentrated urine that may also possess the slight odor of ammonia. Most of the ammonia produced from protein breakdown is converted into urea by the liver, so ammonia is rarely detected in fresh urine. The strong ammonia odor you may detect in bathrooms or alleys is due to the breakdown of urea into ammonia by bacteria in the environment.

About one in five people detect a distinctive odor in their urine after consuming asparagus; other foods such as onions, garlic, and fish can impart their own aromas! These food-caused odors are harmless.

Urine volume also varies considerably. The normal range is one to two liters per day (see the table below). The kidneys must produce a minimum urine volume of about 500 mL/day to rid the body of wastes. Output below this level may be caused by severe dehydration or renal disease and is termed oliguria. The virtual absence of urine production is termed anuria. Excessive urine production is polyuria, which may be due to diabetes mellitus or diabetes insipidus.

In diabetes mellitus, blood glucose levels exceed the number of available sodium-glucose transporters in the kidney, and glucose appears in the urine. The osmotic nature of glucose attracts water, leading to its loss in the urine. In the case of diabetes insipidus, insufficient pituitary antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release or insufficient numbers of ADH receptors in the collecting ducts means that too few water channels (aquaporins) are inserted into the cell membranes that line the collecting ducts of the kidney. Insufficient numbers of water channels reduce water absorption, resulting in high volumes of very dilute urine.

| Urine Volumes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Volume condition | Volume | Causes |

| Normal | 1–2 L/day | |

| Polyuria | >2.5 L/day | Diabetes mellitus; diabetes insipidus; excess caffeine or alcohol; kidney disease; certain drugs, such as diuretics; sickle cell anemia; excessive water intake |

| Oliguria | 300–500 mL/day | Dehydration; blood loss; diarrhea; cardiogenic shock; kidney disease; enlarged prostate |

| Anuria | <50 mL/day | Kidney failure; obstruction, such as a kidney stone or tumor; enlarged prostate |

The pH (hydrogen ion concentration) of urine can vary greatly, from a normal low of 4.5 to a maximum of 8.0. Diet can influence pH; for example, meats lower the pH, whereas citrus fruits, vegetables, and dairy products raise the pH. Chronically high or low pH can lead to disorders, such as the development of kidney stones or osteomalacia (softening of bones).

Specific gravity is a measure of the quantity of solutes per unit volume of a solution and was traditionally easier to measure than osmolarity, which refers to solute concentration expressed as the number of osmoles or milliosmoles per liter of fluid (mOsmol/L). Urine will always have a specific gravity greater than pure water (water = 1.0) because of the presence of solutes. However, laboratories can now directly measure urine osmolarity, which is a more accurate indicator of urinary solutes than specific gravity. Urine osmolarity (the concentration of solutes in a solution) ranges from a low of 50–100 mOsmol/L to as high as 1200 mOsmol/L H₂O.

Protein does not normally leave the glomerular capillaries, so only trace amounts of protein should be found in the urine, approximately 10 mg/100 mL in a random sample. If excessive protein is detected in the urine, it usually means that the glomerulus is damaged and is allowing protein to “leak” into the filtrate.

As you previously learned in another lesson, ketones are byproducts of fat metabolism. Finding ketones in the urine suggests that the body is using fat as an energy source in preference to glucose. In diabetes mellitus, when there is not enough insulin (type I diabetes mellitus) or because of insulin resistance (type II diabetes mellitus), there is plenty of glucose; however, without the action of insulin, the cells cannot take it up, so it remains in the bloodstream. Instead, the cells are forced to use fat as their energy source, and fat consumed at such a level produces excessive ketones as byproducts. These excess ketones will appear in the urine. Ketones may also appear if there is a severe deficiency of proteins or carbohydrates in the diet.

Moreover, nitrates (NO₃⁻) occur normally in the urine. However, gram-negative bacteria metabolize nitrate into nitrite (NO₂⁻), and the presence of nitrite in the urine is indirect evidence of infection. Knowledge of the presence of nitrite in the urine can help identify the specific bacteria causing infection, such as the relatively common Escherichia coli, which can allow for better, more specific antibiotic treatment options.

Furthermore, there should usually be no blood found in the urine of a healthy individual. Recall that the glomeruli filter the blood based mostly on particle size, so large elements like blood cells are excluded. Therefore, blood in urine (called hematuria) usually means trauma to the urinary system itself, like bleeding from the kidneys, ureters, bladder, or urethra. This can indicate issues such as urinary tract infections or kidney stones. However, blood cells may sometimes appear in urine samples as a result of menstrual contamination in females, and this is not an abnormal condition.

Now that you understand what the characteristics of urine are, the next lesson will introduce you to how you store and dispose of this waste product and how you make it.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.