Table of Contents |

Although an antiwar movement quickly mobilized after Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in late 1964, most Americans supported President Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam.

Support for the war began to ebb as the draft expanded and more American troops were deployed in Southeast Asia. Although the United States identified itself as a friend of the South Vietnamese, U.S. soldiers found themselves in a strange environment thousands of miles from home, where many people resented their presence and aided the National Liberation Front (NLF), also known as the Viet Cong.

The NLF, with assistance from the North Vietnamese army, often used guerrilla tactics rather than conventional military methods. Surprise attacks, booby traps, and similar practices led to a growing number of American casualties.

EXAMPLE

By April 1966, more Americans were being killed in battle than South Vietnamese soldiers.Frustrated by the losses, General William Westmoreland, the commander of American troops in Vietnam, called for the United States to take more responsibility for fighting the war. President Lyndon B. Johnson also urged Americans to “stay the course,” even as opposition to the war grew. In November 1967, Westmoreland claimed that the end of the war was in sight.

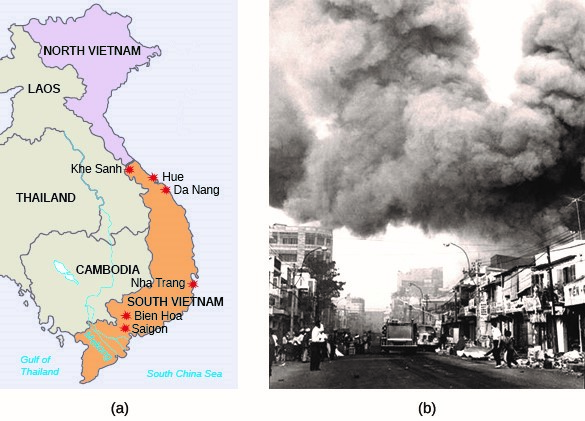

Westmoreland’s assurances were called into question when, in January of 1968, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong launched the Tet Offensive, their most aggressive assault on South Vietnam.

During the offensive, North Vietnamese forces and Viet Cong guerrillas attacked nearly 100 cities in South Vietnam, including the capital, Saigon.

Despite heavy fighting, American and South Vietnamese forces responded quickly and recaptured all the locations that had been taken by communist forces. The communists suffered far more casualties than the United States, but television coverage of the offensive shocked U.S. viewers. The potential impact of the offensive was discussed on nightly news programs for weeks.

The Tet Offensive was the first event that led Americans to question whether the war would end soon. It also raised doubts about whether the Johnson administration was telling the truth about the state of affairs in Vietnam. Fueled by graphic images and on-the-scene news coverage, public opinion began to turn against the war in Southeast Asia.

During the spring and summer of 1968, two assassinations and continuing racial unrest combined with the Vietnam War to throw the Democratic Party’s domestic agenda into disarray.

Political observers assumed that, as the incumbent, Lyndon Johnson would have the support of most Democratic voters. However, thanks to a campaign run largely by student volunteers, McCarthy won the New Hampshire primary on March 12, 1968. His success in New Hampshire encouraged Robert Kennedy, the brother of President Kennedy and the former U.S. attorney general, to also announce his intention to run for the Democratic nomination for president. Lyndon Johnson, suffering health problems and realizing that the war had damaged his public support, announced in late March that he would not seek reelection. His decision left the race for the Democratic nomination wide open.

As the Democratic Party fell into disarray, Martin Luther King Jr. helped organize a Poor People’s March, which brought thousands of demonstrators to Washington, DC. Their objective was to convince the administration to focus on the War on Poverty instead of the war in Vietnam.

The Poor People’s March reflected an important change in King’s civil rights strategy. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, he did not emphasize poverty and the other economic challenges faced by African Americans. Instead, he focused on integration and voting rights. The Poor People’s March, however, illustrated his growing recognition that racial equality must be accompanied by economic equality.

As a result of this realization, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, in April 1968 to support a strike by the city’s sanitation workers, many of whom were Black. There, he found that the local Civil Rights Movement was divided. Older activists, like King, supported nonviolence and sought integration. They were increasingly challenged by a new generation of activists motivated by the Black Power ideology.

On April 4, King was shot and killed by a White assassin while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

Within hours of the assassination, cities across the nation exploded in violence as African Americans, shocked by King’s murder, burned and looted urban neighborhoods. The riots reinforced the findings of the Kerner Commission (named for Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, who chaired President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders). Johnson formed the commission in July of 1967, following violent race riots in Detroit, Michigan, and Newark, New Jersey.

The Kerner Commission published its report in February 1968, 2 months before King’s assassination. Its conclusions were stark and reinforced the perception that racial and economic inequality were intertwined.

The Kerner Commission

“This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal . . . .

To pursue our present course will involve the continuing polarization of the American community and, ultimately, the destruction of basic democratic values.

The alternative is not blind repression or capitulation to lawlessness. It is the realization of common opportunities for all within a single society.

This alternative will require a commitment to national action—compassionate, massive, and sustained, backed by the resources of the most powerful and richest nation on this earth. From every American it will require new attitudes, new understanding, and, above all, new will.

The vital needs of the nation must be met; hard choices must be made, and, if necessary, new taxes enacted . . . .

Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans.

What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain, and white society condones it.”

The Democratic primary elections of 1968—and the presidential election that followed them—occurred during this period of racial unrest and growing frustration with the Vietnam War.

During the California primary in June 1968, the Democratic campaign for president was struck by violence. Shortly after giving a speech to celebrate his close victory over Eugene McCarthy, Robert Kennedy was shot by a Jordanian immigrant, Sirhan B. Sirhan. Kennedy died 26 hours later.

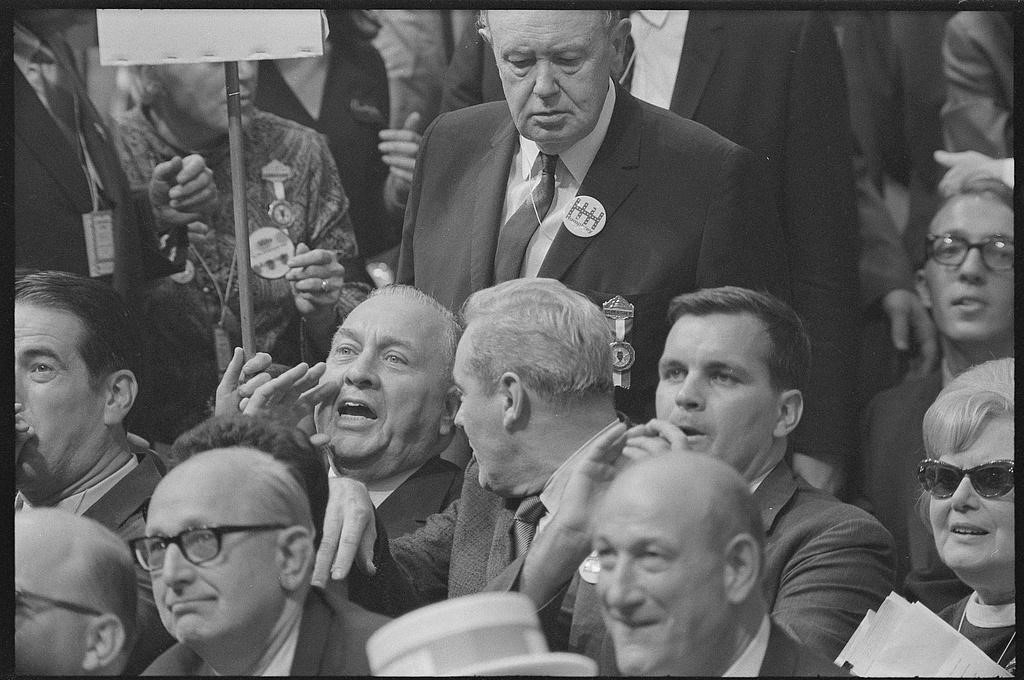

By the time the Democratic Party convened for its convention in Chicago, in August 1968, it was in complete disarray. Some factions insisted on their right to a hearing. Others, most notably members of the antiwar movement, attempted to disrupt the convention altogether.

To maintain law and order, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley mobilized 12,000 city police officers, 6,000 Illinois National Guardsmen, and 6,000 U.S. Army soldiers. Television cameras captured what happened when this force encountered protesters—outside the convention hall and at other locations in the city. Armed officers advanced on crowds of protesters, clubbing some of them and setting off tear gas canisters. The protesters fought back, and the city descended into chaos.

The situation inside the convention hall was also chaotic. Senator Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut criticized Mayor Daley’s suppression of dissent when he addressed the delegates. The mayor, who was seated with the Illinois delegation, responded hostilely as Ribicoff spoke.

Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic nomination for president, but events at the Chicago convention showed that his party was deeply divided.

The images of violence, which contributed to a growing public impression that things were spinning out of control, seriously diminished Humphrey’s chances of victory in 1968. Many liberals and young antiwar activists, disappointed by his selection over Eugene McCarthy (and still upset by the death of Robert Kennedy), did not vote for Humphrey. Other Democrats, and American voters in general, were shocked by the violence they saw in Chicago and believed the party was courting dangerous radicals.

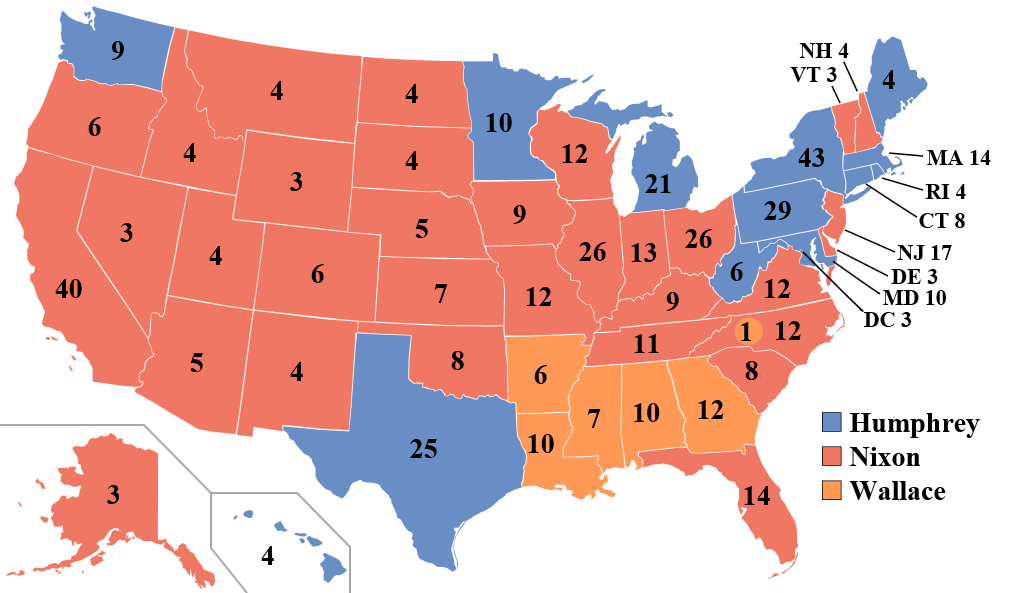

As the Democratic Party unraveled, the Republican candidate for president, Richard Nixon, successfully campaigned for the votes of working- and middle-class White Americans to win the 1968 election.

Nixon later referred to these voters as the silent majority, based on the belief that the Great Society’s racial and economic reforms ignored the interests of White, working-class, and middle-class citizens.

According to Nixon, these voters comprised the majority of Americans who were upset by the social changes taking place in the country. Antiwar protests offended many Americans’ sense of patriotism. Race riots seemed to indicate a collapse into chaos. Nixon’s supporters also did not agree with the Kerner Commission’s conclusion that White America was partly to blame for urban unrest and decay.

Nixon’s promise to achieve stability, and his emphasis on law and order, appealed to the silent majority. Nixon pledged to take a strong stand against racial unrest and antiwar protests and harshly criticized the Great Society. He also claimed to have a plan that would end the war in Vietnam honorably and bring the troops home.

Hubert Humphrey and Richard Nixon received nearly the same number of popular votes during the 1968 election (approximately 31.3 million votes for Humphrey and 31.8 million for Nixon). However, Nixon won the Electoral College, 301 to 191. Running on a pro-segregation, third-party ticket, George Wallace received close to 10 million votes. He was especially successful in the South, where he won five states.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Kerner Commission, Report of Natl Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, ret from: bit.ly/1sYRtw6