Table of Contents |

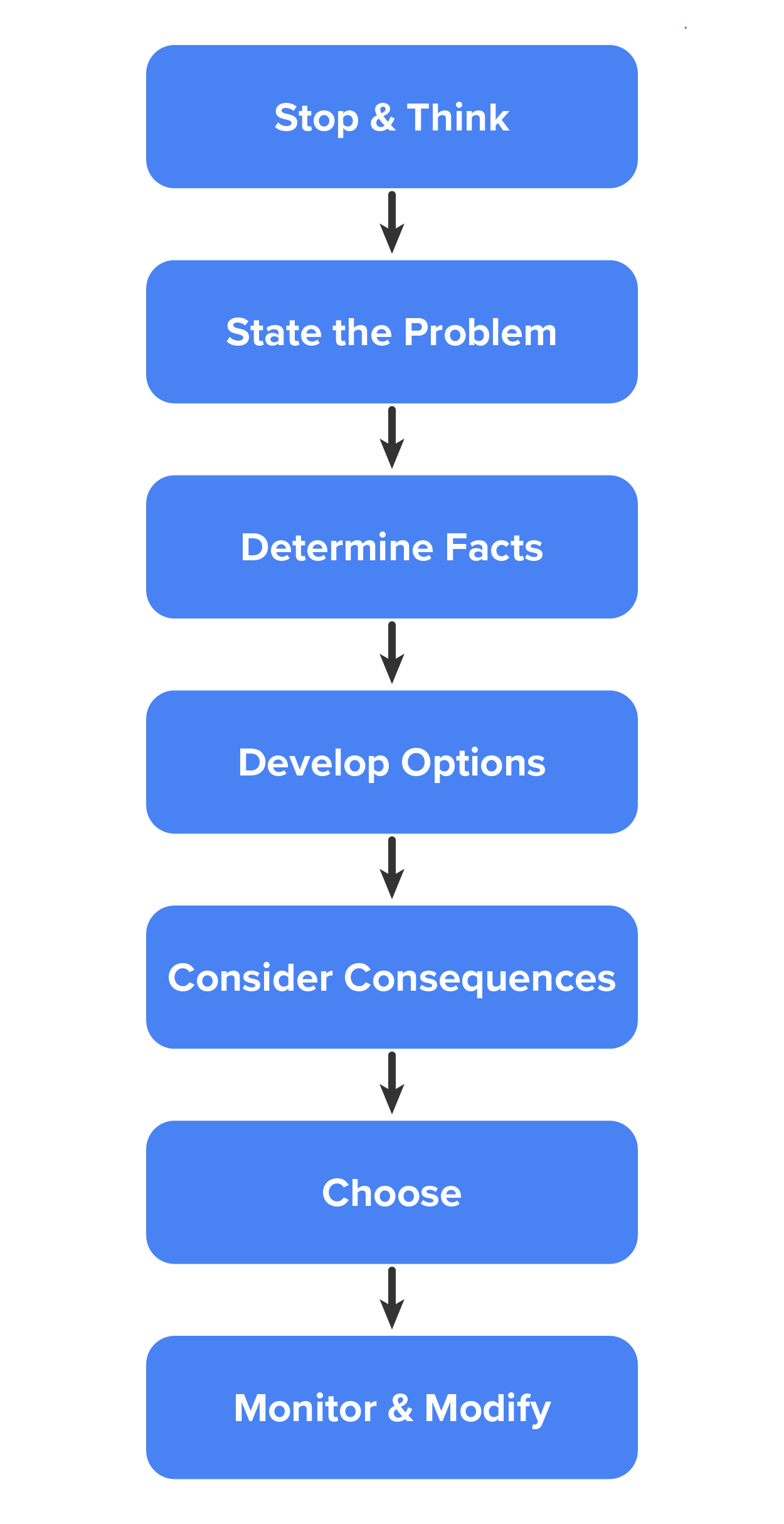

While the pyramid can help you think through a problem, it does not necessarily help you arrive at a solution. The Seven-Step Path to Decision Making is a problem-solving model developed by Michael Josephson (n.d.) that is easy to follow and can be applied to ethical problems. It is also more useful to lead a group in a discussion. While it is not limited to ethical decisions, the truth is that most problems do have an ethical dimension. Briefly, the seven steps include:

EXAMPLE

Three experienced chefs open a restaurant with a substantial investment from a fourth party. They are told that restaurants are often not profitable the first year, and that it would be alright in the long term. However, due to good reviews and “buzz,” the restaurant does very well the first year and surpasses their budget expectations. The restaurant owners meet to discuss how to use the money. This scenario will continue for each of the steps.First, three questions to consider:

In order to define or state the problem in a clear statement, you may need to consider background information like the norms, customs, or traditions in an organization. Is there a code of conduct? You may need to take it up a level, to an industry level, or even a national or international level. Does the profession have ethical and moral codes of professionalism? Are there any applicable laws to follow?

Next, you may need to consider which ethical theory you will use to guide your business ethics decision. Are you focusing on consequences, moral principles that precede the situation or context, or both? Are you considering the means and intentions as well as the outcomes? What is the ethical framework to make (and justify) your decision? If the ends are most important, how certain are you that they can be achieved? What can you control, and what can you not control?

EXAMPLE

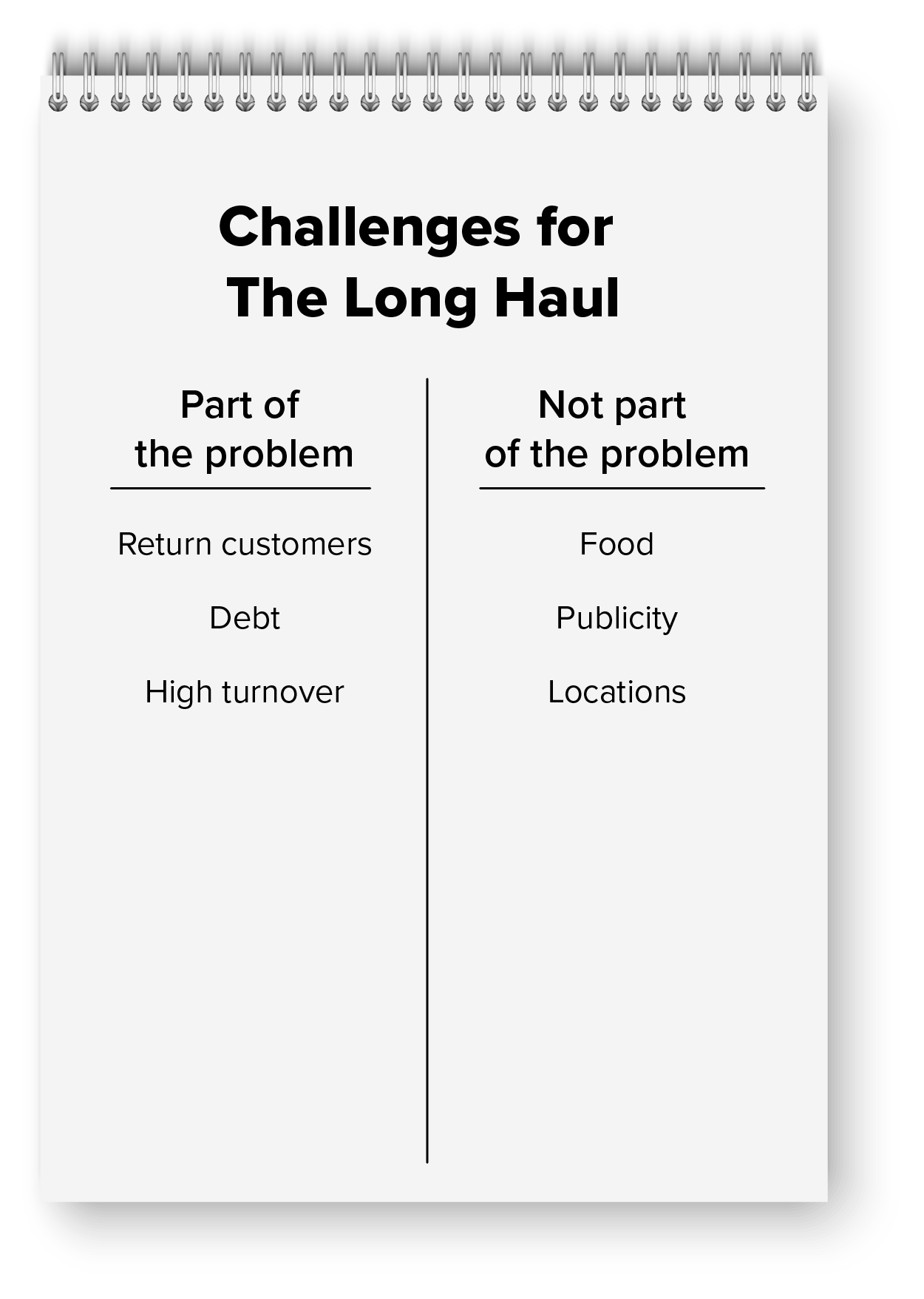

The restaurant owners agree to meet at another location in the morning where they can fully concentrate on the decision before them; the restaurant itself is too noisy and distracting to be a good place to meet. They invite their key investor and a more experienced restaurant manager to help keep them aware of industry standards and best practices. Prior to the meeting, they also get advice from their lawyer on legal use of business profits. As they talk, they think about how to survive the restaurant’s buzz cooling off, addressing customer feedback, the potential challenge of competing restaurants opening on the same street, and how a downturn in the economy would affect the entire industry.Once you have the information available, your first task is to write a clear statement that describes or defines the ethical dilemma. One useful exercise here is to create two lists, one for what is a part of the problem, and the other for what is outside of the scope of this problem, and then write words in each list.

It’s easy to perceive that all factors are part of the challenge or problem, so you need to use good judgment. You need to focus on the key elements that directly relate to the current problem and separate those that only indirectly relate. As you do this step, you might start to see key words and terms that most relate to the problem or ethical dilemma and help clarify your goals.

Once you have assessed the problem or ethical challenge and its many variables, you need to create a written statement that clearly captures the ethical dilemma or the problem you are trying to solve.

EXAMPLE

The restaurant owners come to the agreement that the biggest challenge before them (and thus the best target for their money) is to assure that their restaurant can stay stable for a long time even as the restaurant’s popularity and the economy cool off. They capture this in a short sentence: “Keep the doors open.” But they are also aware that this is not just a strategic problem, but an ethical one. They have many stakeholders, including customers, staff, their investor, and the neighborhood where they operate.After you have a clear definition of the ethical challenge, dilemma, or problem, it is time to determine the facts. Like in the previous step, you might approach this task with two lists; this time, you will list what you know and what you do not know. What you know involves the facts you can point to, document, or otherwise rely on in your consideration of the dilemma. The list of what you do not know might, at first, seem like a tall task, but you can reduce it by focusing on who, what, where, when, why and how as essential questions.

Throughout this step you need to be cautious about reliability and credibility. As you consider what you know (or think you know), you rely on others for information. The sources you rely on become part of your own credibility, and since you are relying on them in this important process, you need to have the best, authoritative facts and information available. Check the facts and verify the information. If trusting the judgment of others, make sure they have the background knowledge, skill, and integrity to provide sound advice.

EXAMPLE

The restaurant owners can make educated guesses about both expenses and profits in the coming year, since they know their current expenses and revenue and can adjust slightly for inflation. Importantly, they have an experienced (and objective) restaurant manager on hand who can give them credible information about what to expect. What they do not know is how bigger economic factors will affect people’s decisions to dine out, or if any new competitors will enter the neighborhood. Considering these factors underlines the need to make positive changes and stay competitive.Next, you will consider your options to resolve this ethical dilemma or problem. As you start, you should write down as many ideas as you can generate. It’s not a time for being feasible or judgmental; this is brainstorming, or a “thought shower,” where the ideas come down and you collect them all. Once you have created a list of options, you can start to consider Plan A vs. Plan B vs. Plan C, or list your options in rank or priority order.

EXAMPLE

The restaurant owners have many ideas for the future of their restaurant. As they discuss how to use the unexpected windfall, a couple of them think of exciting ideas like a food truck, or a pop-up restaurant at a different location, or changing the menu. They write down all the ideas, but then look back to their statement of the problem and realize some ideas do not address the core goal of keeping their doors open. For this, they must invest in the current restaurant. To this end, they identify three less exciting ideas that are more appropriate: increasing wages, buying new furnishings for the restaurant, and changing the menu.Recall that some ethical systems focus only on the principles, regardless of the context or situation, while others focus only on the consequences, outcomes, or results, regardless of the means, motive, intent, or principles. As you have seen previously, neither system completely addresses the ethical dilemma from a holistic perspective, and all options involve tradeoffs, as none are ever perfect. However, you can consider your intentions, or means, and the consequences of your actions.

EXAMPLE

Although their key financial backer is at the meeting (who is related to one of the owners), she does not insist on being repaid or realizing a profit right away; the legal advice has stated they can reinvest the money in the business with her permission. However, one of the restaurant owners does feel it is important to do so before they spend any more money. Another disagrees, suggesting it would be better to improve the restaurant environment. Online reviewers love the food but have said the restaurant itself lacks atmosphere. The third disagrees with both, thinking that improving pay and providing at least some benefits to the staff should be their highest priority.Finally, you will decide on a course of action to resolve the ethical dilemma or problem. This is one of the most difficult steps in the process. It requires you to act, and to take responsibility for your actions. To not choose an option is also an action; its absence also involves principles and consequences, including unintended consequences. Even if you do nothing, “nothing” is a choice and therefore an action. As you come to the decision, you might return to a pro/con list, deciding which option produces the greatest good, promotes the principle(s), or leads to the best possible outcome for everyone. You might even have a pro/con list of making the decision now versus waiting until later.

EXAMPLE

The restaurant owners briefly consider setting the money aside for an emergency but decide that immediate action better serves the long-term interests of the restaurant. They also decide that splitting the money among many different solutions won’t be helpful: they cannot improve the atmosphere without an overhaul, and a modest raise wouldn’t make a big difference to their staff. As they talk through their options, they come to the conclusion—with their investor’s support—that the biggest obstacle to long-term success is the restaurant’s physical space, that they need customers to keep coming back after the food is no longer a novelty. They feel this will ultimately be best for staff, who will have stable jobs, and for their investor, who can look forward to years of returns on her investment.The best-prepared plans change, adapt, and fall apart in the heat of the moment, and ethical challenges are never simple or easy. Still, you can monitor how well the option or plan worked, make adjustments as it develops, and correct errors. No plan is perfect.

As an ethical businessperson, you are responsible to yourself, your family, your community, your field or profession, your industry, your nation, and your world. That can seem overwhelming, but you need to focus on what you can control, and how your ethical decisions impact others. You need to continually ask yourself what world you want to live in, and what world you want for those that come after you. You should consider how your actions ripple across the planet. It all starts with you and your choices. You choose to act (or not to act) and any decision, principled or unprincipled, has consequences.

EXAMPLE

Before moving forward, the restaurant owners share their decision with staff. When they get some pushback, the owners remember that they are not only following industry standards, but setting them. Their decisions about how to treat staff will ripple throughout the local restaurant community. Higher wages would pressure other restaurants to do the same, for example. With that in mind, they revise their plan to include at least a cost-of-living adjustment to salaries, which does lower the budget for improving the interior. They offset this by deciding to not hire an interior decorator, as they had planned, but using their own judgment in how to plan the furnishings and décor. Furthermore, they are transparent with their staff about their decision making, explaining that they want to not just provide good jobs to staff, but long-term jobs, which requires further investment in the establishment.Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.

REFERENCES

Josephson, M. (n.d.) The Seven-Step Path to Better Decisions. Josephson Business Ethics. josephsononbusinessethics.com/2010/10/the-seven-step-path-to-better-decisions/