Table of Contents |

The Constitution specifies that members of the House of Representatives serve two-year terms whereas senators serve six-year terms. Per the Supreme Court decision in U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton (1995), there are currently no term limits for either senators or representatives, despite efforts by many states to impose them in the mid-1990s (Table 1). That means there is no limit to the number of times that members of Congress can be reelected.

Table 1 Representation in Congress

| House of Representatives | Senate | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Members | 435 | 100 |

| Number of Members per State | Based on population | 2 |

| Length of Term of Office | 2 years | 6 years |

| Minimum Age Requirement | 25 | 30 |

The Constitution also states that every state will have two senators, regardless of population. Therefore, with fifty states in the Union, there are currently one hundred seats in the Senate. Senators were originally appointed by state legislatures, but in 1913 the Seventeenth Amendment was approved, which specified that senators would be elected by popular vote in each state.

Seats in the House of Representatives are divided up among the states based on each state’s population. The House has a total of 435 representatives and each represents approximately the same number of people. However, each state is guaranteed at least one seat in the House, regardless of population.

The process of dividing up the seats in the House, which is called apportionment, occurs every ten years.

To ensure that representation is proportional to the overall population of a state, congressional apportionment is achieved through the equal proportions method, which uses a mathematical formula to allocate seats based on U.S. Census Bureau population data. The census is conducted every ten years as stipulated by the Constitution. At the close of the first U.S. Congress in 1791, there were sixty-five representatives, each representing approximately thirty thousand citizens. As the territory of the United States subsequently expanded, sometimes by leaps and bounds, the population requirement for each new district increased as well. Adjustments were made, and the roster of the House of Representatives continued to grow until it reached 435 members after the 1910 census. Ten years later, following the 1920 census, Congress failed to reapportion membership, and finally, in 1929 an agreement was reached to permanently cap the number of seats in the House at 435.

EXAMPLE

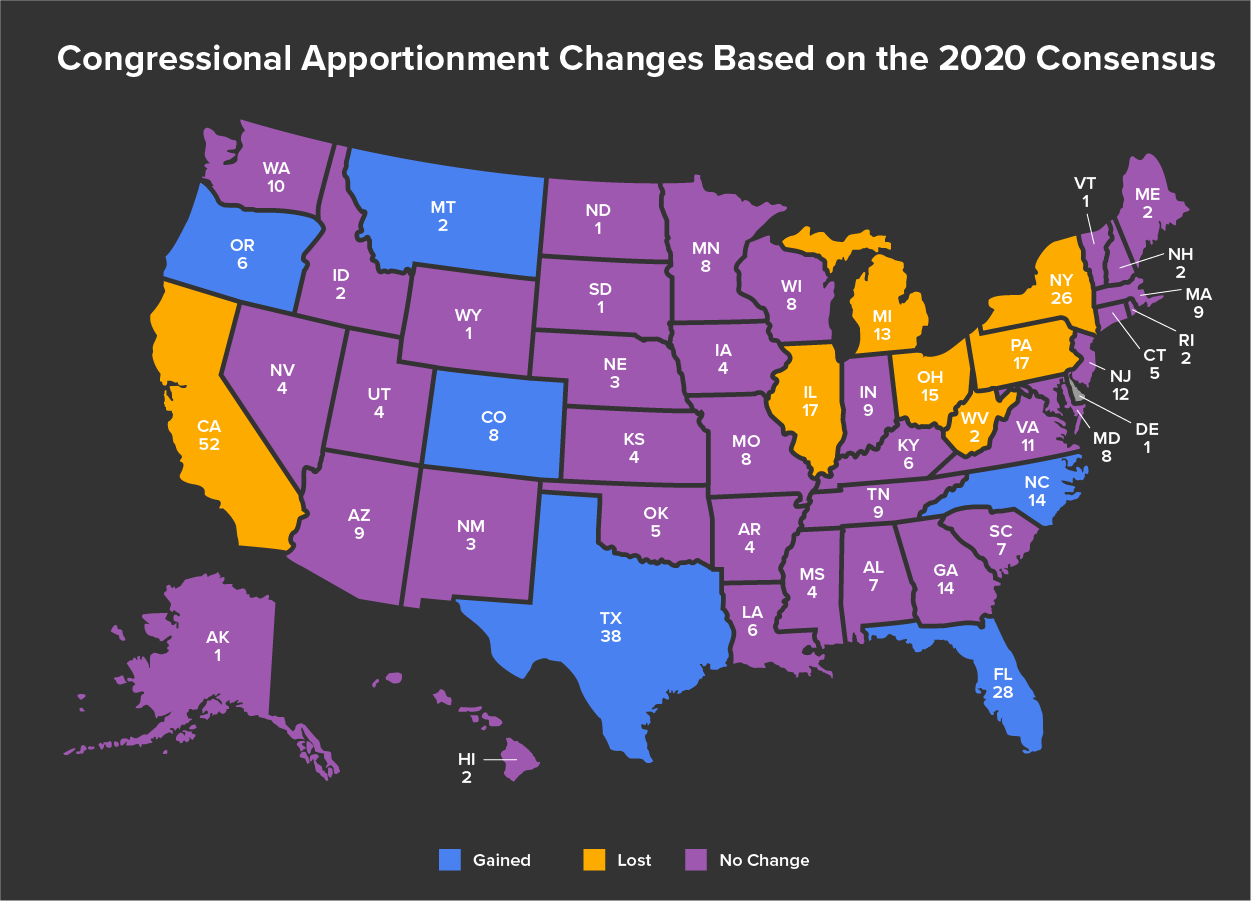

Currently, there are seven states with only one representative in the House: Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. The most populous states, California and Texas, have a total of fifty-two and thirty-eight congressional districts (Figure 1). Each member of the House is elected by voters in a specific congressional district.

Because the number of seats in the House is capped at 435 seats, every ten years Congress must reapportion the seats of the House to reflect population changes between states. Each state must also create House districts that have roughly the same population. Because local areas can see their population grow or decline over time, adjustments in district boundaries are typically needed. As a result, states must draw new boundaries for House districts to ensure that these districts are relatively equal in population size. This is achieved through redistricting, which also occurs every ten years after the U.S. Census has established how many persons live in each state and where. This process guarantees that Congress meets the principle of “one person, one vote.”

The system is imperfect, and there are challenges related to the size of each representative’s constituency—the body of voters who elect the representative. The average number of citizens in a congressional district now exceeds 700,000. This is arguably too many for House members to remain very close to the people. George Washington advocated for thirty thousand per elected member to retain effective representation in the House. There is also the problem of Washington, DC. There are approximately 675,000 residents of the federal district of Washington (District of Columbia). Since Washington, DC is not part of a state, these citizens do not have voting representation in the House or the Senate. Like those living in the U.S. territories, they only have a non-voting delegate.

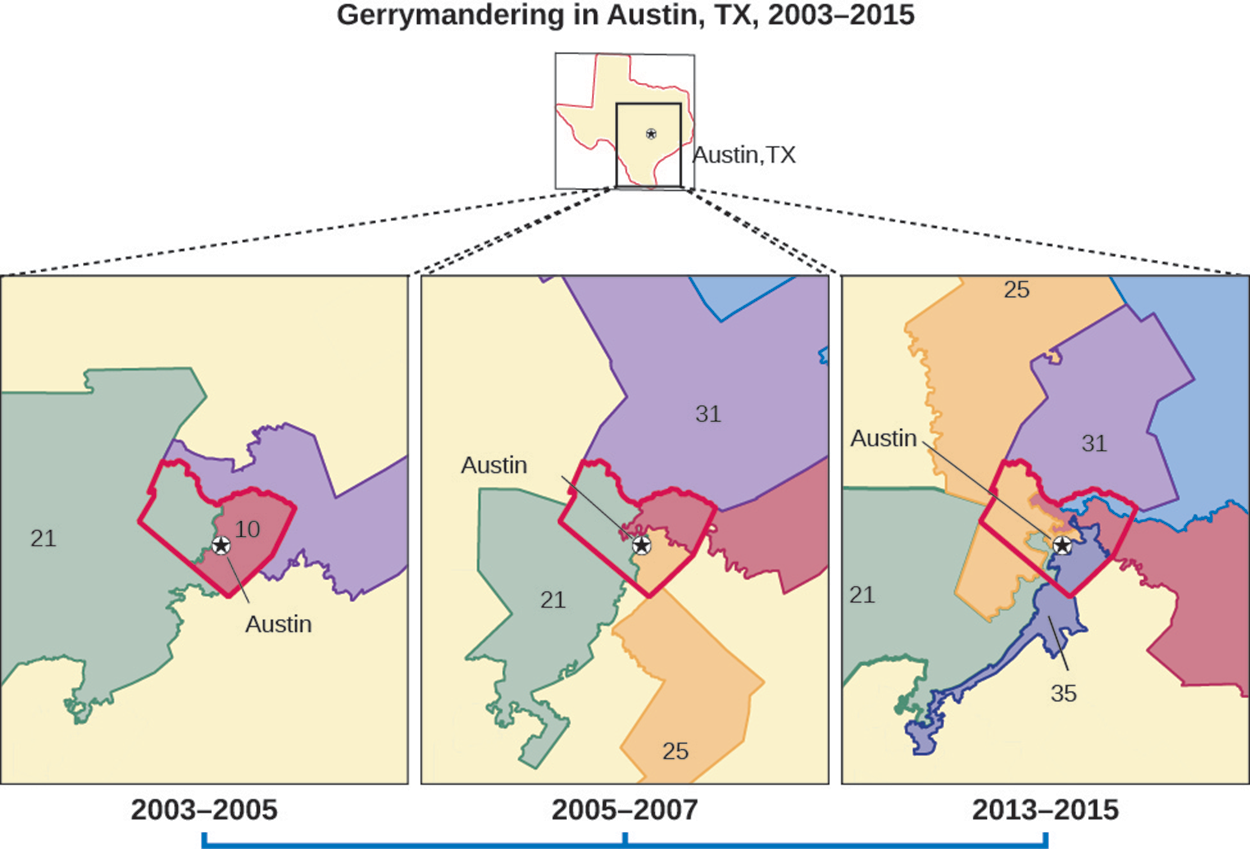

The stalemate in the 1920s that led to Congress capping the number of seats in the House at 435 was not the first (or the last) time that reapportionment resulted in controversy. Gerrymandering, the manipulation of district boundaries as a way of favoring a particular candidate or political party, has long been a problem in American politics. The term combines the word salamander, a reference to the strange shape of these districts, with the name of Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry, who in 1812 signed a redistricting plan designed to benefit his party.

Despite the questionable ethics behind gerrymandering, the practice is legal and both major parties have used it to their benefit. Gerrymandering is frequently employed in states where a dominant party seeks to maintain that domination (Figure 2). Gerrymandering can be a tactic to draw district lines in a way that creates “safe seats” for a particular political party. Sometimes, however, parties in the state legislature agree to draw districts that provide a clear majority for each party—so that there are safe seats for both parties. In Democratic-controlled states like Maryland, there are more safe seats for Democrats than Republicans. In Republican-controlled states like Louisiana, there are more safe seats for Republicans.

Although gerrymandering is legal, state legislatures have set guidelines for how the state redistricting body can redraw the district. These differ from state to state, but Table 2 outlines several common guidelines.

Table 2 Common Guidelines for Redistricting.

| Redrawn districts should… |

|---|

| Be compact and have a geometric shape. |

| Be contiguous (all parts of the district must be connected). |

| Respect existing political subdivisions, such as city lines. |

| Not divide communities of interest, such as neighborhoods or areas with shared political interests. |

| Try to maintain the integrity of prior districts (to provide continuity of representation). |

IN CONTEXTWhile the strangely drawn districts succeeded in their stated goals, nearly quintupling the number of African American representatives in Congress in just over two decades, they have frustrated others who claim they are merely a new form of gerrymandering.

In Ohio, one skirts the shoreline of Lake Erie like a snake. In Louisiana, one meanders across the southern part of the state from the eastern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, through much of New Orleans and north along the Mississippi River to Baton Rouge. And in Illinois, another wraps around the city of Chicago and its suburbs in a wandering line that, when seen on a map, looks like the mouth of a large, bearded alligator attempting to drink from Lake Michigan.

These aren’t geographical features or large infrastructure projects. Rather, they are racially gerrymandered congressional districts. Their strange shapes are the product of careful district restructuring aimed at enhancing the votes of minority groups. The alligator-mouth District 4 in Illinois, for example, was drawn to bring a number of geographically autonomous Latino groups in Illinois together in the same congressional district.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “AMERICAN GOVERNMENT 3E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/AMERICAN-GOVERNMENT-3E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

National Conference of State Legislatures. (n.d.). Redistricting Criteria. www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-criteria-legisbrief.aspx