Table of Contents |

Another stage of western expansion occurred when the settlers of Missouri petitioned Congress for statehood. The Missouri Territory had been organized out of the massive Louisiana Purchase that Thomas Jefferson orchestrated in 1803. By 1818, tens of thousands of settlers had flocked to the territory, bringing over 10,000 enslaved people with them. When the status of Missouri was taken up by the U.S. House of Representatives in early 1819, its admission to the Union would be no easy matter, since it brought to the surface a violent debate over whether slavery could expand into a new state.

American politicians had sought to avoid the issue of slavery ever since the 1787 Constitutional Convention, when delegates arrived at the Three-Fifths Compromise.

In short, the compromise ensured that the free population of a state, along with 60 percent of its enslaved population, would be counted when determining the number of that state’s members in the House of Representatives. A concession to southern slave states—which featured large enslaved populations—the Three-Fifths Compromise inflated the political influence of southern states in the House of Representatives and in the Electoral College. From the perspective of representatives from northern states—where racial slavery had gradually ended—the admission of Missouri as a slave state would threaten the tenuous balance between free and slave states in the Senate. Northern politicians were particularly concerned that the South’s interests in protecting slavery would result in the creation of a southern voting bloc in Congress that would overwhelm northern, “free” states.

The debate over representation shifted quickly to the morality of slavery itself when New York representative James Tallmadge—a Democratic-Republican who opposed slavery—attempted to introduce a provision to the Missouri statehood bill known as the Tallmadge Amendment. The amendment proposed the admission of Missouri as a free state, on the condition that the introduction of additional enslaved persons to Missouri be prohibited and that the children of enslaved women already in Missouri be emancipated at age 25.

The amendment sparked two years’ worth of controversy, during which time the unity of the Democratic-Republican party ruptured along sectional lines.

Northern representatives supported the Tallmadge Amendment, denouncing slavery as immoral and against the nation’s founding principles of equality and liberty. Southerners in Congress rejected the amendment as an attempt to gradually abolish slavery—not just in Missouri but throughout the Union—by violating the property rights of slaveholders, and their freedom to take their property wherever they wished.

Despite opposition from southern representatives, the Tallmadge Amendment passed the House of Representatives. The amendment died in the Senate, however, leaving the fate of Missouri up in the air amidst threats of party division and calls of disunion.

Democratic-Republican Party leadership—most notably President James Monroe, Representative Henry Clay of Kentucky, and Senator Jesse Thomas of Illinois—interpreted the Tallmadge amendment as a threat to party unity. They worked behind the scenes to ensure that Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state.

What came to be known as the Missouri Compromise consisted of three parts:

Although the compromise quelled the issue of Missouri statehood, it did not quell the debate over slavery in the United States, especially in the western territories. Such a debate led many, including Thomas Jefferson, to fear for the future of the republic.

Thomas Jefferson expressed such concern in a letter to John Holmes on April 22, 1820, shortly after the Missouri Compromise was enacted. A selection from his letter is provided below:

Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Holmes

“This momentous question [over slavery in Missouri], like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper….

I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves, by the generation of ‘76, to acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be that I live not to weep over it….”

The expansion of the franchise among White men—combined with the political paralysis and sectional divides that the Democratic-Republicans experienced during the Missouri crisis—contributed to a new style of political party organization. This process was most evident in New York, under the leadership of Senator Martin Van Buren.

Van Buren was indicative of the new form of American democracy that was taking hold by the early 19th century. Rather than an intellectual or a member of the elite, which typically characterized the Founding Fathers (and the first six presidents), Van Buren came from a modest background and was the son of a tavern keeper. In addition, unlike George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, whom Americans celebrated for their virtue or intellect, Van Buren’s significance lay in his skill as a political operative.

During the 1820s, Van Buren’s Democratic-Republican faction, known as “Bucktails,” gained political power by cultivating the loyalty of a majority, rather than by catering to an elite family or renowned figure.

One of the Bucktails’ most significant political achievements in New York came in organizing a convention to revise the state constitution in 1821. Here, the Bucktails successfully pushed through an amendment that did away with the property qualification for voting, giving all White men in the state the right to vote.

At the same time that the Bucktails catered to White voters by eliminating the property qualification, they played to White voters’ racist sentiments by enacting a significant property qualification for Black voters, who had to have a net worth of $250 to be eligible to vote.

The Bucktails also altered the process involved with appointing local officials such as sheriffs and county clerks. Under the original constitution, a Council of Appointments selected these officials. The Bucktails replaced this process with a system of direct elections, which meant thousands of jobs immediately became available to candidates who had the support of the majority. In practice, Van Buren’s faction could nominate and support candidates for these offices, based on their loyalty to the party.

In this way, Van Buren helped create the foundations of a political machine, one in which his faction maintained key alliances with other New York politicians, and rewarded the loyalty of disciplined party members. Not only did it help transform New York politics, Van Buren’s tactics introduced a new term to American political nomenclature: the spoils system.

Van Buren also had larger plans. Like many of his colleagues in Congress, he was concerned with how quickly the political system fell along sectional lines during the Missouri crisis, and he believed that a new party system could prevent such conflict in the future. Whereas the Founding Fathers interpreted political parties as factions that catered to specific interests, Van Buren believed that parties could be used as tools in favor of the public interest. Competition among party members could provide voters with a choice. Likewise, parties could create coalitions that transcended section, thus preventing a breakdown in the political system as had almost occurred during the Missouri crisis.

The fact that the American political system became paralyzed once again during the presidential election of 1824 reinforced Van Buren’s concerns. The election of 1824 showed that a one-party system (the Democratic-Republicans) was no longer sustainable. At a time when the people were taking a keener interest in politics, the election also revealed frustrations with the Electoral College, which the Founders had implemented to suppress the will of the people.

The gradual disappearance of property qualifications for voting among White men contributed to tens of thousands of new voters in the 1824 election. With the arrival of these new voters, the traditional system of having members of Congress form a caucus to determine who would run for president no longer worked. These voters had local and sectional interests, and they voted on them accordingly. For the first time in American history, the popular vote mattered in a presidential election.

EXAMPLE

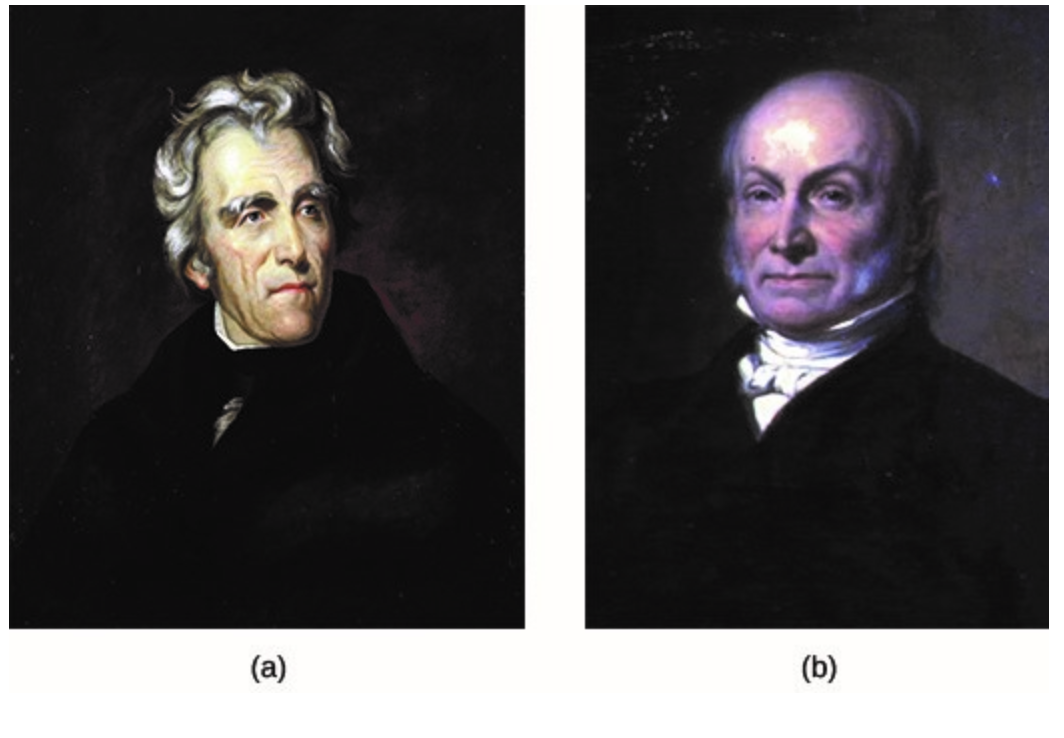

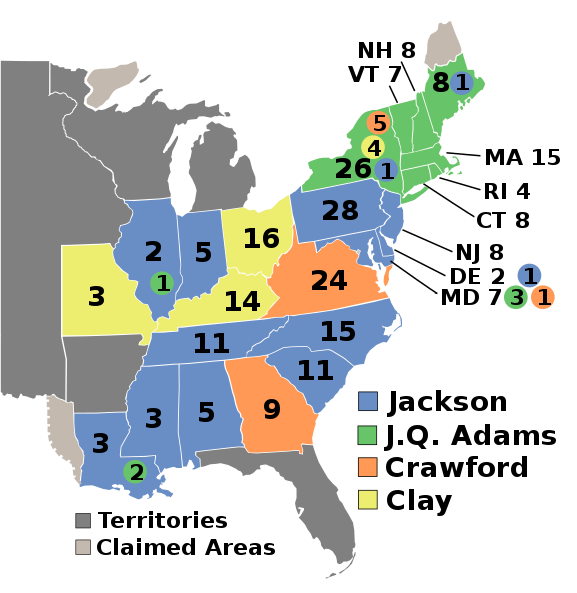

For the 1824 election, electors for the Electoral College were chosen by popular vote in 18 states, while the six remaining states used the older system in which state legislatures chose electors.With the caucus system under attack, the presidential election of 1824 featured four presidential candidates, all of whom ran as Democratic-Republicans, and most of whom could claim only sectional support. The crowded field included:

Jackson won the popular vote, receiving over 153,000 votes. The Electoral College was another matter, however. Given the number of candidates in the field, no one received a majority of the electoral votes (see map below).

Of the 261 electoral votes up for grabs, the successful candidate needed to secure 131 or more votes to secure the presidency. Jackson carried the most states, but received only 99 electoral votes. Adams, with much of his support centered in the Northeast, won 84. Crawford and Clay received 41 and 37 electoral votes, respectively.

Given the stalemate in the Electoral College, the election fell to the House of Representatives, per the requirements of the Twelfth Amendment.

Since the Twelfth Amendment also stipulated that the House would consider only the top three candidates for president, Henry Clay, who had received the fewest electoral votes, was automatically eliminated. However, as Speaker of the House, Clay went on to play a tremendous role in deciding the election.

Clay believed that Adams was the best qualified presidential candidate and he saw Jackson, who hailed from neighboring Tennessee and a fellow westerner, as a rival who might prevent himself from ascending to the presidency someday. For these reasons, Clay worked within the House to secure the presidency for Adams. Upon winning the House vote, Adams promptly appointed Clay as Secretary of State.

Andrew Jackson and his supporters cried foul. To them, the election of Adams reeked of anti-democratic corruption. So too did the appointment of Clay as secretary of state. All said, the affair seemed a "corrupt bargain," in which Clay and Adams exchanged votes for a public appointment while ignoring the popular vote.

Such a bargain seemed to embody everything that an emerging American democracy, based on the will of the people and majority rule, was now against. Everywhere, Jackson’s supporters vowed revenge against the anti-majoritarian result of 1824.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL