Table of Contents |

Conflict is not just a mental or emotional experience; it also has a profound physiological component. Our bodies play a significant role in how we perceive, react to, and manage conflict. Understanding this connection between our physiological responses and our behavior during conflict is essential for developing effective strategies to manage and resolve disputes.

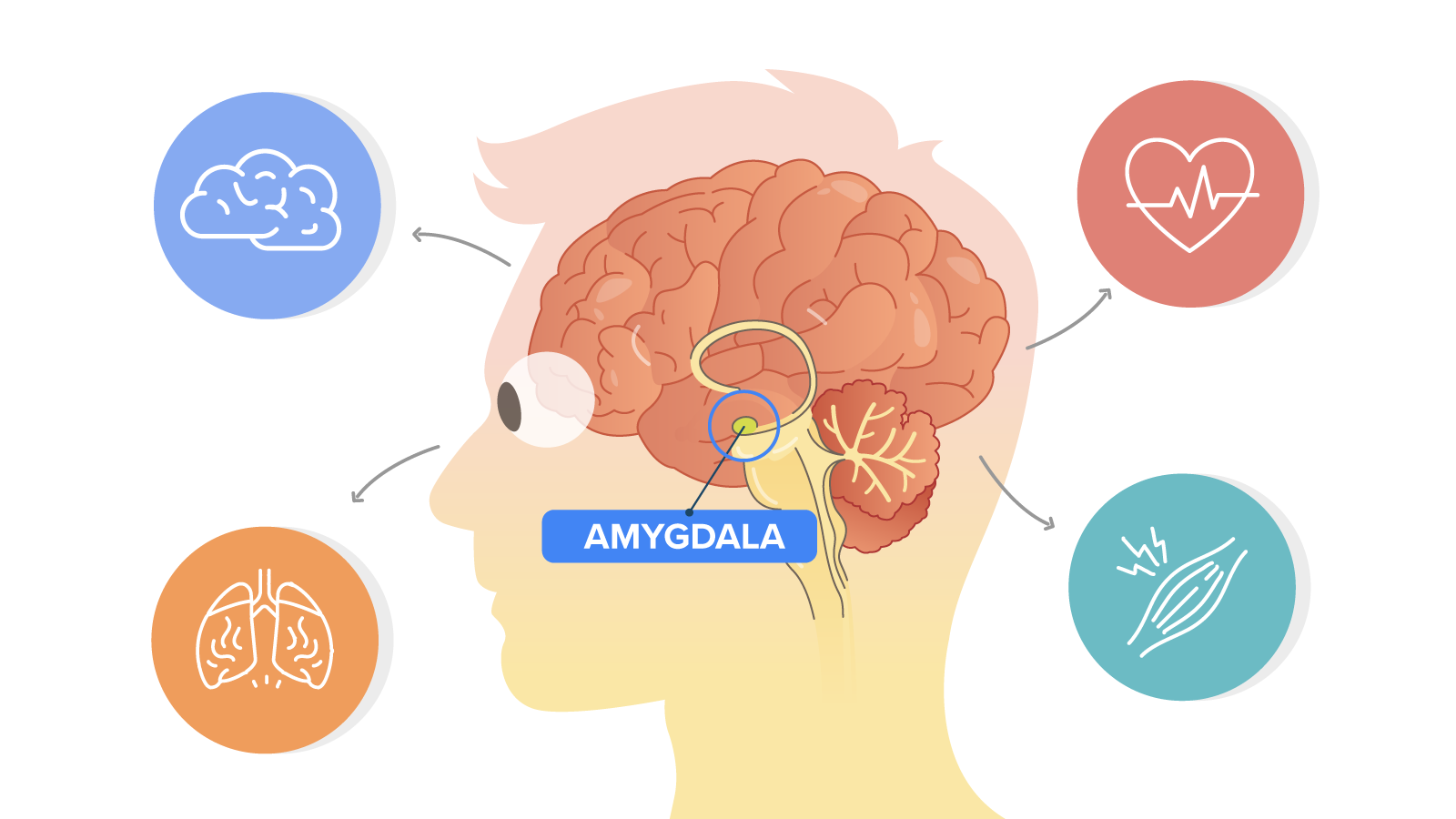

In this lesson, we will explore the intricacies of how our bodies respond to conflict, starting with the brain’s role in initiating these responses. We’ll explore how the amygdala, a small but powerful part of the brain, triggers automatic reactions when we perceive a threat, leading to what is commonly known as a “fight-or-flight” response. This response can dramatically influence how we behave in conflict situations, often escalating tensions if left unchecked.

The lesson is structured into two main sections to guide you through this complex interplay between physiology and conflict. In the first section, we’ll explore the amygdala, our reactions, and the science behind a fight-or-flight reaction. We’ll also explore how the amygdala interprets threats, both real and perceived, and how this interpretation sets off a cascade of physiological changes in our bodies. These changes can affect everything—from our heart rate and breathing to our ability to think clearly and make rational decisions. You’ll see how these automatic responses can sometimes escalate conflicts, even when the threat is not as serious as our bodies might lead us to believe.

In the second section, we’ll navigate strategies for managing physiological responses during conflict. This includes knowing how our bodies react, which is only part of the equation, as well as practical strategies for managing these physiological responses when they occur. From techniques like deep breathing and taking a break to more advanced methods of raising our “reaction threshold,” this section will provide tools to help you respond to conflict in a more controlled and thoughtful manner. We will also discuss how building confidence and using rational assessment can help mitigate the intense emotional and physical responses that often accompany conflict situations.

Throughout this lesson, you will have opportunities to reflect on your own experiences with conflict. By the end of this lesson, you will have a deeper understanding of how your body’s physiological responses influence your behavior during conflict and how you can manage these responses to better navigate and resolve disputes.

Let’s begin by looking at the role of the amygdala in triggering our physiological responses during conflict and how these reactions can influence the way in which we handle disagreements.

The amygdala is a structure in the brain that helps us interpret stimuli as either a threat or a nonthreat, which then initiates the body’s fight-or-flight reaction. This automatic response prepares the body to either confront or flee from perceived danger. During this process, the hormone adrenaline is released, causing physical changes such as an increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and tense muscles, all of which equip the body to respond effectively in conflict situations.

When we encounter a situation that our brain perceives as threatening, the amygdala kicks into high gear. This small, almond-shaped part of our brain is responsible for triggering the fight-or-flight reaction—a survival mechanism that prepares us to either confront or escape the danger.

EXAMPLE

Imagine you’re walking in a park at night, and suddenly you hear rustling in the bushes. Your heart races, your muscles tense, and you may feel an overwhelming urge to either run away or prepare to defend yourself.This is your amygdala at work, interpreting the rustling as a potential threat and triggering your body’s fight-or-flight response.

However, the amygdala doesn’t always differentiate between a real threat, like a wild animal, and a perceived threat, such as public speaking or a difficult conversation at work. Both situations can trigger similar physical reactions—sweaty palms, a rapid heartbeat, shallow breathing—even though the actual danger may be minimal.

When you enter a conflict, your amygdala might misinterpret the situation as a significant threat, triggering a fight-or-flight response. This can lead to behaviors that escalate the conflict, such as raising your voice, becoming defensive, or withdrawing from the conversation entirely.

EXAMPLE

Consider a situation where you’re having a heated discussion with a colleague. As the conversation becomes more intense, you might feel your body reacting—your voice gets louder, your heart races, and you might even feel the urge to walk away.These reactions, driven by the amygdala, can make it difficult to think clearly and resolve the conflict effectively.

Our physiological reactions to perceived threats can have a significant impact on how we handle conflict. It’s essential to understand the difference between automatic reactions and conscious responses.

EXAMPLE

If someone criticizes your work during a meeting, your immediate reaction might be to defend yourself or criticize them in return.This reaction is automatic, driven by your amygdala’s perception of the situation as a threat. However, if you take a moment to pause and choose your response, you might decide to calmly ask for clarification or suggest discussing the issue further after the meeting.

Automatic reactions, which are not consciously chosen, can escalate conflicts, making it harder to reach a resolution. In contrast, conscious responses, which we choose deliberately, allow us to stay calm, think clearly, and address the situation more effectively.

EXAMPLE

Imagine you’re in a team meeting and a colleague dismisses your idea without explanation. Your immediate reaction might be to feel insulted and argue back. However, if you take a moment to breathe and respond consciously, you might choose to ask your colleague for more feedback or suggest revisiting the idea later in the discussion.Now that we understand the role of the amygdala and how our physiological reactions can impact conflict, let’s explore strategies to manage these responses effectively.

When we find ourselves in stressful or conflict-ridden situations, our body’s automatic response can often make things worse. The amygdala—the part of our brain responsible for triggering a fight-or-flight reaction—doesn’t distinguish between real, immediate danger and perceived threats, such as a heated argument or a stressful conversation. This can lead to heightened emotions, quick reactions, and escalated conflicts.

To manage these physiological responses effectively, it’s important to employ strategies that help calm the mind and body. Relaxation techniques are one of the most effective ways to counter the adrenaline-fueled responses initiated by the amygdala. Relaxation doesn’t mean ignoring or avoiding conflict; instead, it involves consciously reducing unnecessary tension in the body and mind, allowing us to approach the situation with a clearer head and a calmer demeanor.

Breathing exercises are a powerful tool for relaxation. When we are stressed, our breathing often becomes rapid and shallow, which can increase feelings of anxiety and panic. By slowing down our breathing, we can stimulate the body’s parasympathetic nervous system, which helps to calm our heart rate and reduce the production of stress hormones like adrenaline. Practice taking deep, slow breaths from your diaphragm—breathe in slowly through your nose, hold for a moment, and then exhale slowly through your mouth. Even just a few minutes of focused breathing can make a significant difference in how you feel and how you respond to a conflict.

Taking a break is another effective strategy. When emotions run high, it’s easy to say or do things we might regret later. By stepping away from the situation, even if only for a few minutes, we give ourselves the opportunity to cool down and reflect. This break allows the initial surge of adrenaline to subside, making it easier to think more rationally and respond more thoughtfully when we return to the conversation. Whether it’s a brief walk, a few moments of quiet reflection, or simply taking a pause before responding, giving ourselves this space can prevent a conflict from escalating and lead to a more productive resolution.

Incorporating these strategies into our approach to conflict can not only help manage our physiological responses, but also improve our overall communication and relationship-building skills. By taking control of our body’s automatic reactions, we empower ourselves to handle conflicts with greater calmness, clarity, and confidence.

When we find ourselves in a conflict, our bodies might be flooded with adrenaline, making it challenging to think clearly and act rationally. However, several techniques can help us manage this adrenaline response and prevent it from escalating the conflict.

One of the most effective ways to calm our body’s fight-or-flight response is to focus on our breathing. Taking slow, deep breaths from our stomach can lower our heart rate and reduce tension.

Sometimes, the best way to manage a heated situation is to step away from it for a moment. Taking a break—counting to 10, going for a walk, or simply taking a few minutes to cool down—can help you regain composure.

After calming yourself, it’s essential to think about how you’ll respond both verbally and nonverbally. Lowering your voice and maintaining open body language can help de-escalate the situation.

One way to manage your physiological responses in conflict is to raise your reaction threshold, which is the level of potential threat necessary to trigger a fight-or-flight response, making it less likely that you’ll react impulsively to perceived threats.

Confidence, or belief in your own ability, plays a crucial role in managing stress and can significantly raise your reaction threshold, making you less likely to respond impulsively with a fight-or-flight reaction in challenging situations. The key to building confidence lies in preparation and experience, both of which help you feel more in control and capable when faced with stressors.

When you are well prepared and have had positive experiences in similar situations, your brain is less likely to perceive the scenario as a threat, reducing the likelihood of an automatic, adrenaline-fueled reaction. This is particularly true in conflict situations that typically induce stress, such as confronting a colleague about a disagreement. For example, if you have a history of tense conversations escalating into arguments, practicing conflict resolution skills in a controlled setting—perhaps through role-playing or mediation workshops—can be incredibly beneficial. This practice not only enhances your communication skills but also gradually desensitizes you to the fear and anxiety associated with conflicts. As you gain more experience and successfully navigate difficult conversations, your confidence grows. Over time, you may notice that what once triggered intense physical reactions—such as a racing heart, clenched fists, or a raised voice—now feels more manageable. Instead of reacting impulsively with anger or defensiveness, you can approach the conflict with a calm, composed mindset, enabling you to address the issue more effectively and maintain control over the situation.

EXAMPLE

If you’re worried about an upcoming performance review, instead of thinking, “This is going to be terrible; I’ll probably get criticized,” try reframing your thoughts to, “This is an opportunity to learn and grow. I can handle whatever feedback I receive.” Or, if you’re anxious about having a difficult conversation with a coworker about a disagreement, instead of thinking, “This is going to end badly; we’ll probably just argue,” try reframing your thoughts to, “This conversation is a chance to clear the air and find a solution. I can approach this calmly and listen to their perspective as well.”This shift in mindset can help you approach the conversation with more confidence and openness, reducing the likelihood of conflict and fostering a more constructive dialogue.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY MARLENE JOHNSON (2019) and STEPHANIE MENEFEE and TRACI CULL (2024). PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.