Table of Contents |

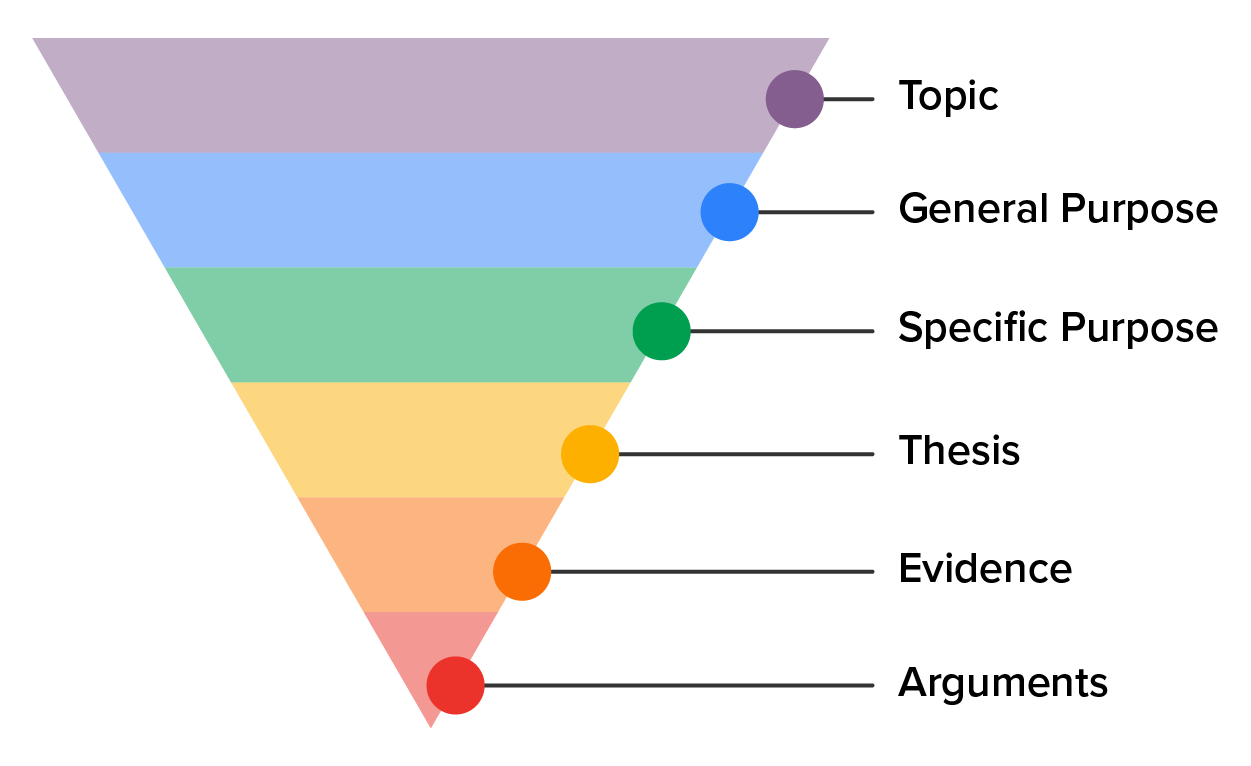

Think of a speech as an inverted pyramid. The pyramid's widest point is the topic of the speech. Once you have determined your topic, you should consider what the general purpose of your speech is, followed by your specific purpose, which will be discussed in the next section. Once your purpose is established, you should begin to refine your thesis, identify evidence, and create supporting arguments. As you follow these steps, the pyramid gets narrower and narrower. It’s important to take the broad view first because getting too caught up in specific arguments or evidence might confuse your audience or cause them to miss the point. It can be easy to focus on that narrowest point, especially if you are very knowledgeable about your topic, but it is just as important to take a step back.

First, we will discuss the purposes of your speech, both general and specific, and then we will get into the rest of the inverted pyramid. After you determine your topic, you should refine it into the general purpose and specific purpose by asking yourself what you hope to accomplish with your speech and what you hope your audience will take away with them.

From a broad standpoint, the speaker should ask, “What do I hope to achieve with the speech? Is the aim to inform? Persuade? A little of both, perhaps? Or maybe entertain?”

There are four basic types (and thus, purposes) of speeches:

IN CONTEXT

Imagine a basic speech topic, such as social media. Consider the audience: To whom will the speaker be speaking? What's their age and knowledge base? A crowd of college students might have a much wider knowledge base than, say, a group of elderly audience members—but not necessarily! There are plenty of grandmothers who could run circles around a twenty-year-old on Instagram or Facebook, and the user demographics of social media are changing as we speak.

If the general purpose is to instruct, the speaker may demonstrate how to set up privacy settings on a social media platform. As they further hone the purpose and thesis of their speech, it might include instruction about why it is important to specify one's privacy settings—with the purpose of persuading the audience.

Now imagine a speaker who wants to convince an audience—for example, an elderly crowd—to adopt a technology like Instagram. The speaker may have to do some instruction, but they will also want to talk about the social benefits of developing a digital network or the cognitive benefits of lifelong learning and technology use. Again, this speech takes a topic like social media and refines it down to a purpose, like persuasion. From there, the speaker can begin to craft a thesis such as, “Social media is a valuable tool for the elderly to remain connected to their loved ones while simultaneously boosting cognition and memory affected by aging.”

Whatever the purpose of the speech, before diving into the specifics of the thesis, the speaker must take a step back to examine the broad, general purpose of why they are speaking. The speaker will want to ensure that every piece of evidence and thought in the speech connects to that general purpose to present a reinforced theme to the audience.

Let’s go back to that inverted pyramid. As the speaker refines their purpose, the speech narrows to its most specific point. The widest part represents the topic, followed by the speech's general purpose (instructing, informing, persuading, or entertaining). The next most refined level is the specific purpose, which fuses the topic and general purpose.

EXAMPLE

If the topic is social media and the speaker's intention is to inform, the specific purpose would be to inform the audience about social media. The speaker might get more specific by focusing on a narrower subject within the topic, such as Twitter. In this case, the more specific purpose might be to inform the audience about the evolution of Twitter as a social media platform.Going from general to specific is all about refinement. If the speech is too broad, the audience may be confused about what the speaker is saying or trying to achieve. At the same time, the speaker must temper just how specific to get in relation to the audience. How much does the audience already know about the subject? How might their demographics, such as age, gender, culture, and education levels, already inform that knowledge base?

Using the inverted pyramid model to outline exactly how to arrive at the speech's most specific, narrowest point, the speaker should avoid losing the audience by getting too specific at the wrong time.

But what if the speech has more than one purpose? Not all speeches conform strictly to the four general purposes for speaking. Some persuasive speeches may contain elements of informative or entertainment speeches. If this is the case, first identify the most important purpose of the speech. At the end of the day, what exactly is the speech trying to achieve? From there, subordinate the other, more specific purposes.

Just keep picturing the inverted pyramid, getting closer and closer to the most specific points to assist in the refinement process of honing a topic into a specific purpose and a solid thesis with substantive evidence to make a case.

EXAMPLE

When giving a persuasive speech about the rise of Twitter as a dominant form of social media, the speaker's general purpose is to persuade, and the specific purpose is to persuade about the notion that Twitter is a dominant form of social media. But the speaker may have other purposes, to show the "lighter side" of Twitter by talking about how some fake and parody accounts carry more weight than their official counterparts (such as the BP Oil magnate and the fake @BPGlobalPR account in the wake of the Gulf Oil spill in 2010). The speaker is still trying to achieve the specific purpose of persuading the audience to believe that Twitter is a dominant social media platform. Using entertaining anecdotes as part of the strategy would fall under that purpose, not alongside or above it.Your thesis statement should clearly articulate the purpose and main points of your speech. Think of the thesis as the rocket that will guide the spaceship—that is, your speech. It's there at the beginning, and in some ways, it guides the trajectory of your speech.

Defining a thesis is essentially constructing the structural outline of your speech. When you have defined a thesis, you have essentially articulated to yourself what your speech will say, what position you will take up, and what the speech's purpose is.

Use the work that you have done to narrow down the scope of the topic that your speech is about; determine the purpose your speech will serve, and define a thesis to construct the remainder of it.

EXAMPLE

The following table contains examples of topics, purposes, and thesis statements for a speech.| Topic | General Purpose | Specific Purpose | Thesis Statement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work project | Inform team on current status. | Reassure team members that their efforts have paid off. | We are on target to meet our customer deadline. |

| Physical fitness | Inform audience on benefits of exercise. | Persuade them it’s easy to do. | Twenty minutes a day is all it takes to feel better physically and mentally. |

| Adopting a puppy | Instruct on how to train a dog. | Teach basic rules for housetraining a puppy. | Be consistent and you’ll see results more quickly. |

| Budgeting | Inform audience on how to create a budget. | Persuade audience to invest a small amount every month into savings. | A savings account will grow over time and give you peace of mind. |

To craft your thesis, start by looking very generally at your speech:

The thesis should be introduced near the beginning of your speech, usually at the conclusion of the introductory remarks. Its placement there is a way of introducing the audience to your specific topic. It should be a declarative statement stating what position you will argue.

It's also particularly helpful to give a quick outline of just how you plan to achieve those goals in another few sentences immediately following your thesis statement.

At the end of the speech, you should restate your thesis (perhaps in a more concise form) to reassert to your audience what you have argued throughout your speech.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM "BOUNDLESS COMMUNICATIONS" PROVIDED BY BOUNDLESS.COM. ACCESS FOR FREE AT oer commons. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION-SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.