Table of Contents |

To begin with, recall that philosophy is the pursuit of truth. This means philosophy is not just the collection of information. Rather, it places the highest importance on how we go about discovering whether or not something is true.

Here are some of the ways philosophy typically attempts to secure truth:

EXAMPLE

You are reading or listening to this tutorial. A scientist could explain the way your body (e.g., your eyes, ears, etc.) enables you to do this. But philosophy will approach this in a different way: It will ask, “What are your reasons for doing this?”. In other words, it will ask for the ideals or goals that motivate your actions (e.g., self-improvement, pursuit of knowledge, etc.).Thinking about the reasons we have for doing things, and questioning whether or not we think they are good reasons, requires us to go beyond mere observation and instead use arguments and critical thinking.

Not only does philosophy do things that science cannot, it can also improve the sciences. One of the main ways it does this is by revealing beliefs or assumptions that influence scientific activity.

EXAMPLE

A scientist may try to solve food shortage by developing ways for crops to have higher yields (e.g., genetic engineering). A philosopher may reflect on the nature of the problem and show that it is not more food that is needed, but a better distribution of the food we already have, thus pointing the way for scientists to find solutions to food distribution.Scientists are very good at finding solutions to problems, but do not always place the same amount of energy into thinking about whether the problem itself is properly posed. Philosophy can make us aware of the nature of the problems or goals we are responding to.

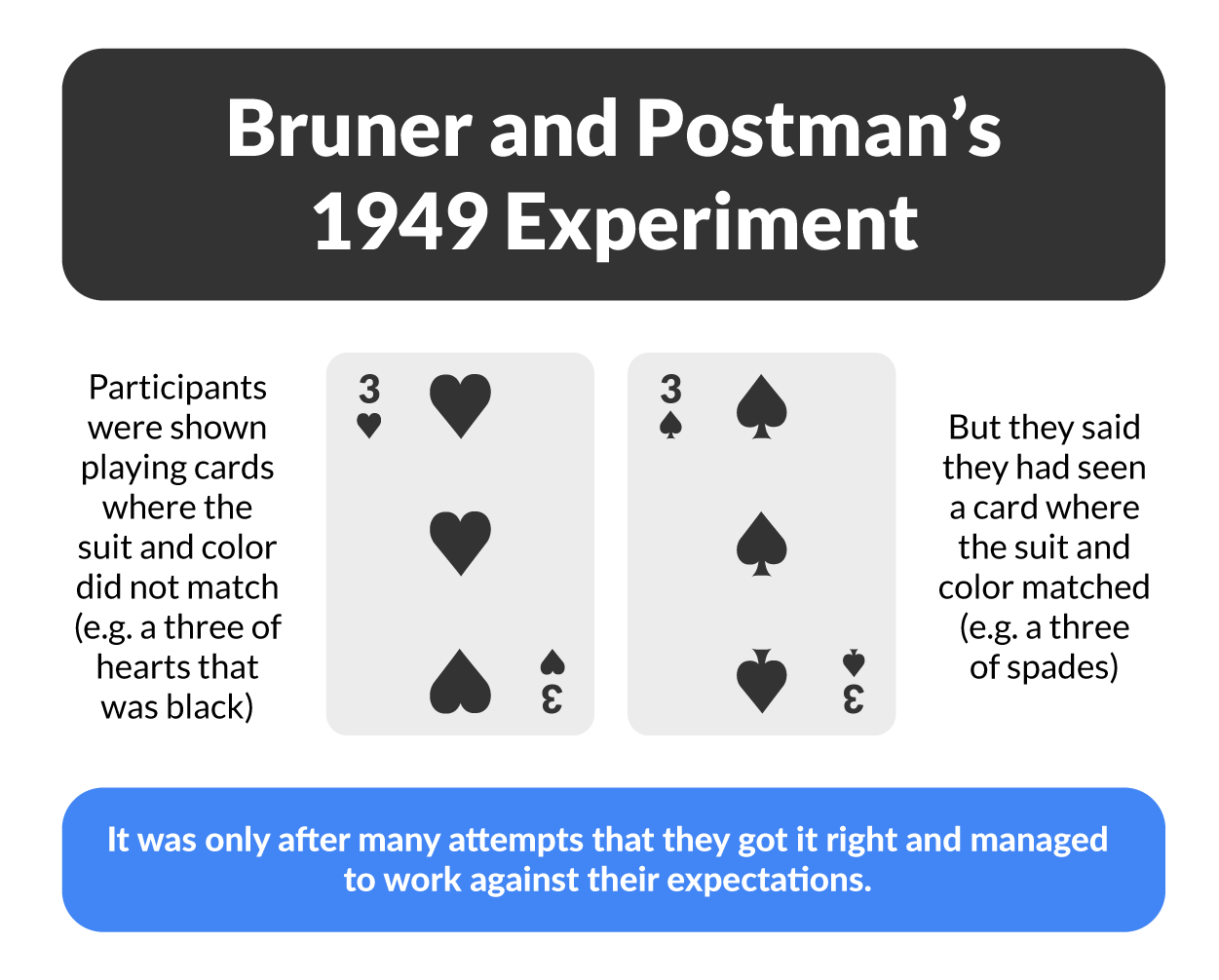

Another way philosophy can help science is by drawing attention to the way that scientists’ observations may be influenced by their expectations.

EXAMPLE

You know that when steel is exposed to oxygen, over time it will rust and turn brown. If you did not know what color copper turns, you might expect to see brown also. And you might think you see it turn brown, even though it actually turns green.You might be thinking, “I would never make that mistake.” And maybe you would not in this example. But you never know when your expectations might influence your perception of things.

Being aware that scientific results may be distorted in various ways leads many scientists to think philosophically about their practice.

EXAMPLE

If a scientist finds evidence that supports her view, she will rarely think that her job is done. Instead, she will repeatedly perform experiments in different ways to try to rule out any biasing factors.As this example shows, a scientist’s job is not finished once she has made an observation. At the very least, she reflects upon the nature of the observation itself, which is a philosophical activity. On top of this, scientists will also need to think about how their results relate to other scientists’ findings.

There are other ways that reflection on science itself yields important scientific results. An important question for social science is whether it should follow the model of the natural sciences. Which way a scientist answers will determine the kind of investigation they do and the discoveries they make.

EXAMPLE

If a social scientist thought they should imitate the natural sciences, then they will try to find law-like regularities in the social world that are as rigid as the laws of nature (such as the law of gravity). If a social scientist thought they should not imitate the natural sciences, they will probably emphasize the element of unpredictability in human action.A lot of what we have been talking about revolves around willingness to question ourselves. But this should not make us think that we should give up having beliefs altogether.

You can have a belief without being completely certain about it.

From experience, you know that the weather forecast is not always correct. So you know that you cannot be completely sure of the weather based on this evidence. By making the strength of your belief dependent on the strength of the evidence on hand, your belief is a rational one.

For your belief to be rational, you consider the evidence both for and against. You must weigh up all the available evidence and let that guide your belief. Remember, it is not enough to have an opinion in philosophy, you need to justify your claims.

EXAMPLE

When philosophers debate about whether abortion is morally permissible or not, they do not take seriously everyone’s opinion on the matter, only those that can give well-reasoned arguments in support of their view.We have been comparing and contrasting science and philosophy in various ways. We have seen that philosophical approaches, though distinct from non-philosophical ones, can complement them.

Let’s look at some other non-philosophical approaches to see how they relate to philosophical approaches. Consider the topic of human mortality or death, for instance, and see how each approach offers different types of questions.

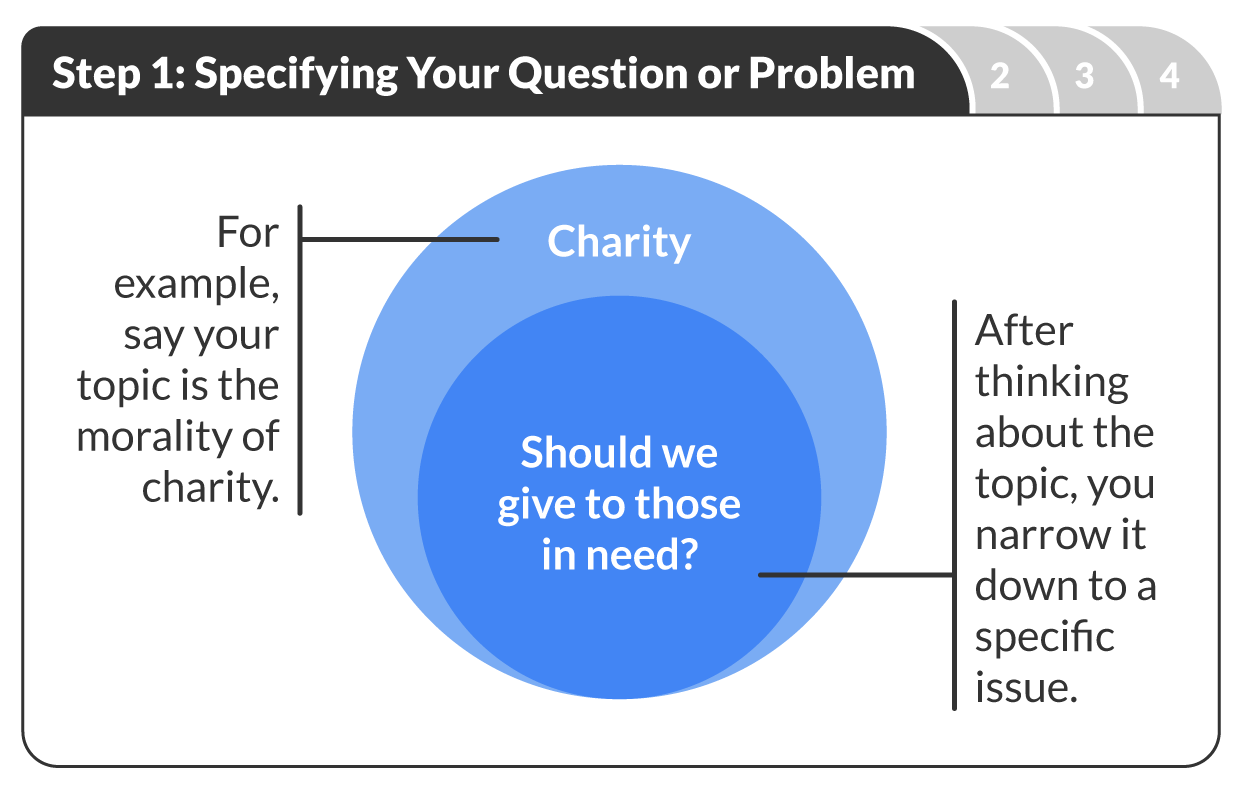

This provides the focus you need to pursue a productive philosophical inquiry.

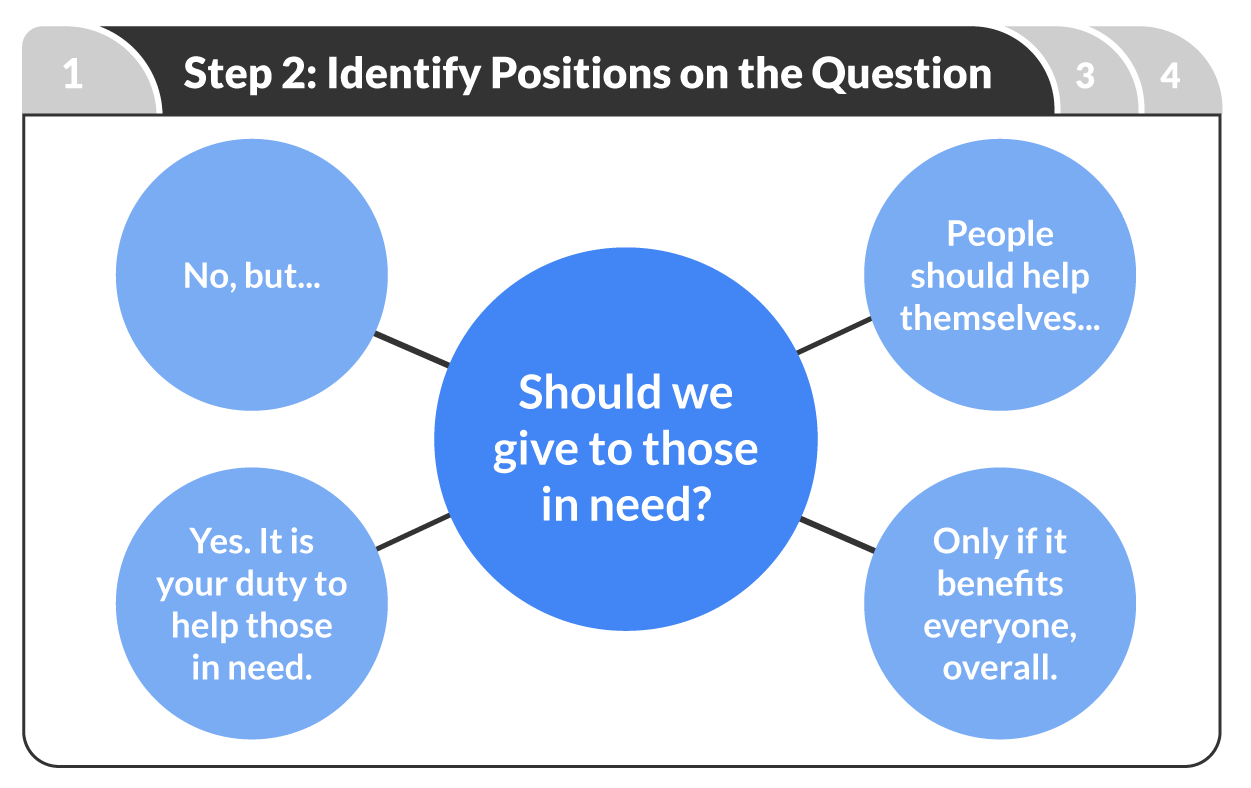

Now you can investigate what other people have already said about it. It is helpful to list many philosophers’ positions on this question before you decide which ones to tackle. See the examples in the illustration below.

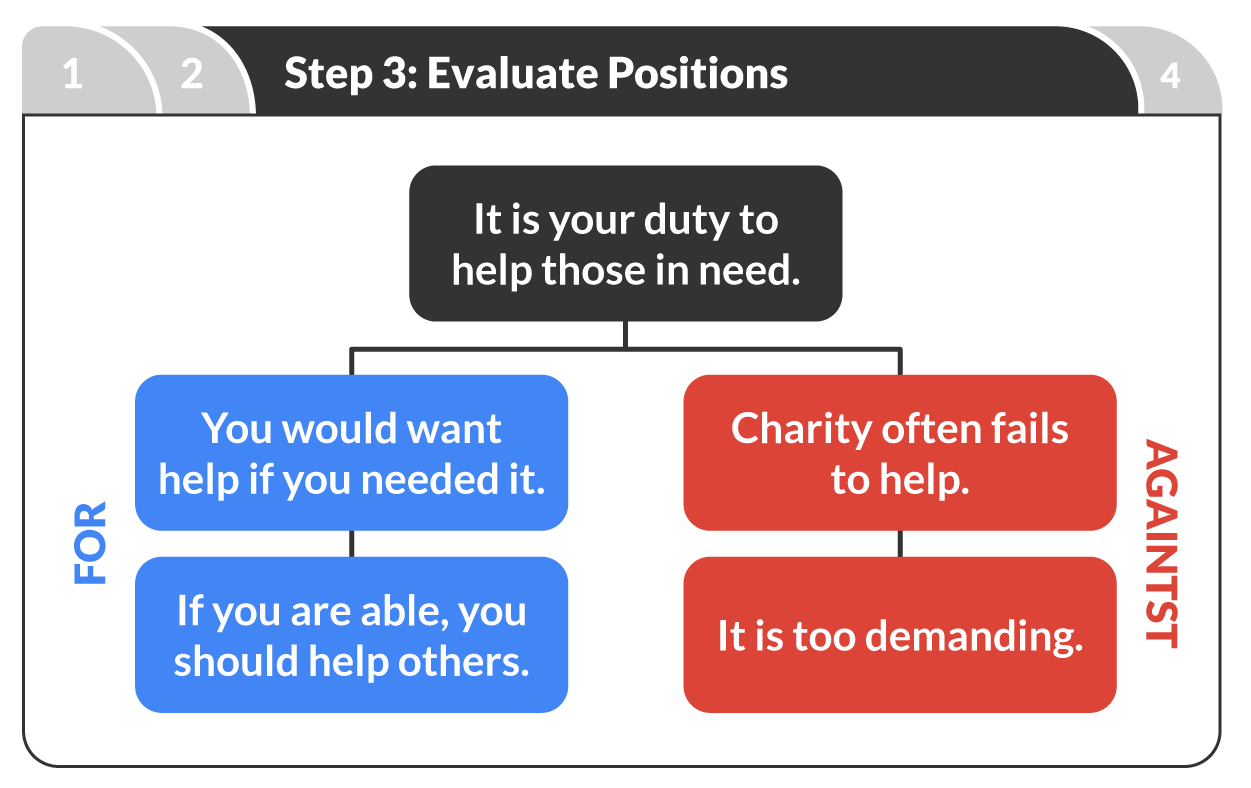

You should then think critically about what has been said by others, weighing up the strengths and weaknesses of their position. Consider the example given in the illustration below.

The type of support you give for or against a position can be of different kinds.

EXAMPLE

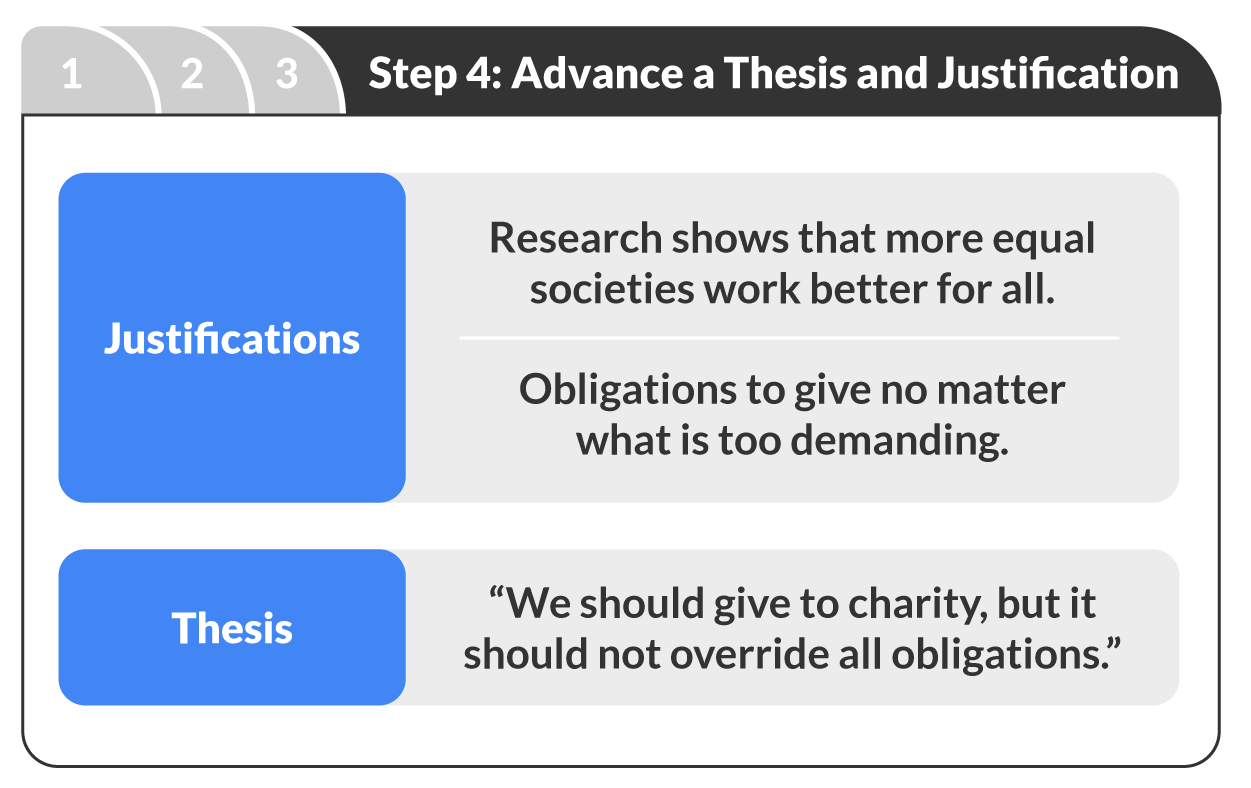

It may be that you cite research that shows charity often fails to help because of inefficient systems. Perhaps you found some convincing arguments by various philosophers that state, "If you are able, you should help others." And maybe you think the reason why we should give to charity is because you find it intuitively plausible to think that you would want to be helped if you needed it.Finally, you need to take a position on the issue and give justifications for why this is the correct position to take. In other words, you should advance a thesis with some supporting arguments or evidence, as shown below.

Notice that the first and second justification pull in slightly different directions. The first seems to be a straightforward endorsement of charity, while the second seems to place doubts on it.

But what is doubted is only the belief that charity is the most important or binding moral commitment we have. The worry with this belief is that, if charity comes above all other obligations, then it might take over our lives (e.g., We would not be able to buy a home because there are those that need food first).

Therefore, you can hold that we ought to give to charity, but add that this is not an obligation above all others. In this way, you would have firmly established a thesis whilst taking varying ideas into account.

Source: This tutorial has been adapted from OpenStax " Introduction to Philosophy ". Access for free at . License: Creative commons attribution 4.0 international. Additional content was adapted from Philosophical Ethics .