Table of Contents |

In 1877, the United States lacked the tools—and the desire—to establish a strong position in international affairs. During Reconstruction, the federal government focused on reincorporating the former Confederacy into the Union and consolidating control over the Western territories (and their native inhabitants). As a result, it did not take any significant initiative in foreign affairs.

EXAMPLE

In 1865, the U.S. State Department, which oversees American foreign policy, had approximately 60 employees and no ambassadors to represent American interests abroad. Only two dozen American foreign ministers were deployed in key countries; many of them gained their positions through patronage or bribes rather than their diplomatic skill or expertise in foreign affairs.EXAMPLE

A strong international presence required strong military forces—particularly a navy. The United States had scaled back its armed forces following the Civil War. By 1890, the U.S. Navy had been significantly reduced in size, and many of its ships had wooden or iron hulls.The foreign policy objectives of the United States following the Civil War were modest and sporadically pursued. Secretary of State William Seward, who held that position from 1861 through 1869, sought to extend political and commercial influence in two key regions:

| Region | Influence |

|---|---|

| Central and South America (also known as Latin America) |

|

| The Pacific Ocean |

|

Although many in the press mocked the acquisition of Alaska as “Seward’s folly,” the purchase furthered America’s strategic ambitions in the Pacific.

Seward was particularly interested in the Aleutian Islands, the long chain of islands that extends southwest from the Alaskan mainland, believing that they could host valuable fueling stations for American merchant shipping in the Pacific. Unbeknownst to Seward, the purchase also gave the United States access to Alaska’s rich mineral resources, including the gold that triggered the Klondike Gold Rush at the end of the 19th century.

The late 19th century, particularly the 1890s, was a turning point in the development of American imperialism, because of the actions of two key groups.

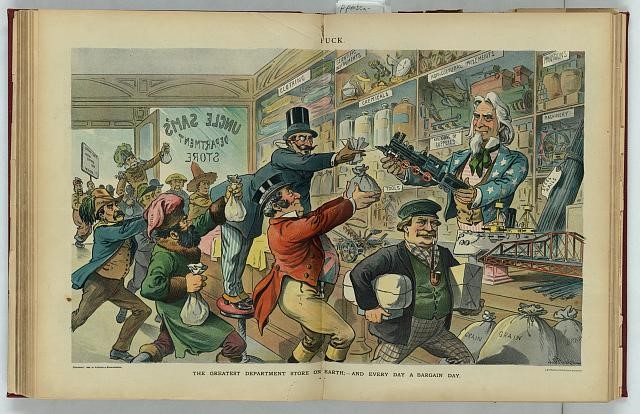

The most important of these groups was the American business community. As the United States began to industrialize in the 1870s, commercial interests called for the country to implement an imperial foreign policy. Businessmen argued that the United States would gain access to international markets for export, and receive better prices on raw materials, by forging new and stronger ties overseas.

As a result of industrialization, American exports to other nations skyrocketed between the Civil War and 1900.

EXAMPLE

Between 1865 and 1875, the value of American exports increased from $234 million to $605 million.EXAMPLE

In 1898, the total value of American exports was $1.3 billion.

Imports also increased substantially during this period.

EXAMPLE

Between 1865 and 1898, the value of imports to the United States increased from $238 million to $616 million.By the 1890s, a number of American entrepreneurs owned businesses or plantations in Latin America and the Pacific. For example, American businessmen owned fruit plantations in Hawaii and sugar plantations in Cuba. Others invested in mining and railroad construction ventures in Mexico and other Latin American nations. Increased investment in these countries also increased U.S. interest in foreign affairs. The other major group—besides the business community—that promoted American Imperialism consisted of Protestant leaders and missionaries. They sought to spread the democratic and Christian influence of the United States abroad.

Many American missionaries were motivated by a combination of ideologies and reform impulses associated with the Gilded Age. These included social Darwinism and the social gospel.

Works like Reverend Josiah Strong’s Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1885) encouraged Protestant missionaries to spread the gospel throughout the world, as in the following excerpt:

Reverend Josiah Strong, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis

“. . . It seems to me that God, with infinite wisdom and skill, is training the Anglo-Saxon race for an hour sure to come in the world’s future. Heretofore there has always been in the history of the world a comparatively unoccupied land westward, into which the crowded countries of the East have poured their surplus populations. But the widening waves of migration, which millenniums ago rolled east and west from the valley of the Euphrates, meet today on our Pacific coast. There are no more new worlds . . . . The time is coming when the pressure of population on the means of subsistence will be felt here as it is now felt in Europe and Asia. Then will the world enter upon a new stage of its history—the final competition of races, for which the Anglo-Saxon is being schooled.

Long before the thousand millions are here, the might centrifugal tendency, inherent in this stock and strengthened in the United States, will assert itself. Then this race of unequaled energy, with all the majesty of numbers and the might of wealth behind it—the representative, let us hope, of the largest liberty, the purest Christianity, the highest civilization—having developed peculiarly aggressive traits calculated to impress its institutions upon mankind, will spread itself over the earth.”

A number of religious leaders and reformers joined Strong in his cause, believing that the expansion of missionary work would not only benefit people around the world but also invigorate American democracy.

Many Protestant sects formed missionary societies that extended their reach into Latin America and Asia. Led by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and similar organizations, American missionaries conflated Christian ethics with American virtues. They spent as much of their time advocating American civilization as they did teaching the Bible.

In keeping with the social gospel, American missionaries wanted to help people in less industrialized nations to achieve a higher standard of living. However, the influence of social Darwinism led them to assume that, without their guidance and assistance, people of non-White races were doomed to a life of poverty and ignorance. Most American missionaries believed that White Americans, and the Anglo-Saxon race they represented, were mentally superior to all others. As Christians, they were required to uplift the inferior races. This view was referred to by British writer Rudyard Kipling as “the White man’s burden.”

The efforts of businesses, missionaries, and reformers supported an expanded American foreign policy in the early 1890s.

American intellectuals, most notably historian Frederick Jackson Turner and naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, justified the goals of American imperialism and suggested the ways in which they could be accomplished. Turner’s frontier thesis, which he presented at the 1893 meeting of the American Historical Association, reflected the concern felt by many American intellectuals that the lack of a frontier in the West could mean the end of American democracy.

Turner concluded that “the demands for a vigorous foreign policy, for an interoceanic canal, for a revival of our power upon our seas, and for the extension of American influence to outlying islands and adjoining countries are indications that the forces (of expansion) will continue.” A foreign policy based on this theory would enable American businesses to find new markets. Turner also encouraged the United States to develop outlets for domestic population growth—for American settlement or to accommodate immigrants.

In 1890, Alfred Thayer Mahan’s guide to how the United States could successfully build an empire, The Influence of Seapower Upon History, was published.

Mahan’s book provided three strategies for the United States to pursue in constructing and maintaining an empire:

Shortly after Mahan’s book was published, the federal government passed the Naval Act of 1890, which set production levels for the creation of a modern naval fleet.

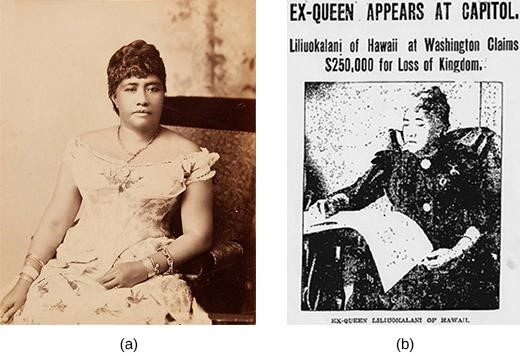

At the same time, the United States consolidated its influence over strategic areas in the Pacific, particularly Hawaii. Although Hawaii was an independent nation, American businessmen exerted significant control over its sugar industry.

EXAMPLE

By 1890, a series of reciprocal trade agreements enabled American sugar producers in Hawaii to export sugar to the United States, tariff-free.When Hawaii’s leader, Queen Liliuokalani, challenged the power of the American sugar companies, businessmen worked with the U.S. minister to Hawaii, John Stevens, to stage a revolt against her in 1893. Hawaii became an American protectorate, and Queen Liliuokalani could do little besides protest that her kingdom had been taken away from her.

The events in Hawaii made it clear that the United States was committed to an imperialist foreign policy and that it was willing to use force to achieve its goals.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Josiah Strong, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1885) pp. 174-75 bit.ly/3Gj9am9