Table of Contents |

What does the word “bureaucracy” conjure in your mind? Long lines at the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) waiting to take a driver’s license test? A monthly social security check arriving in the mail for your retired grandparent or parent? A label on a bottle of medicine that reads “FDA approved”? A free tour of the Smithsonian museums? Though some people think of bureaucracy as a vague, far-off entity that is disconnected from the public, most Americans interact with the bureaucracy on a regular basis and depend on the federal bureaucracy and the programs and services they provide.

Whether local, state, or federal, bureaucracy consists of departments and agencies that carry out the vitally important task of implementing and executing the laws and policies of the government. These tasks include determining who can drive on roads and what foods and medicines are safe to consume, distributing money to the needy, funding scientific research and the arts, building infrastructure, and much more.

Throughout history, nations of all sizes have created agencies that employ non-elected workers to carry out important government tasks. Collectively, these essential workers comprise the bureaucracy. Most of these workers are hired, but in the U.S., some are appointed by the president, the governor, or other officials in the executive branch. The country’s many bureaucrats or civil servants—the individuals who work in the bureaucracy—fill necessary and even instrumental roles in every area of government, from high-level positions to clerks and staff.

Bureaucracy may seem like a modern invention, but bureaucrats have served in governments for nearly as long as governments have existed. Archaeologists and historians point to the sometimes elaborate bureaucratic systems of the ancient world, from the Egyptian scribes who recorded inventories to the Chinese astronomers who kept track of the calendar and predicted lunar eclipses.

Bureaucracies, whether ancient or modern, have common characteristics. These include a hierarchical structure, a tendency to grow larger, and a system by which individuals with expertise are hired.

Bureaucracies all share a common structure. Each agency has a stated overall function and a hierarchy of offices or officers that carry out tasks in order to fulfill that function. A typical bureaucracy can be described by an organizational chart that establishes a clear chain of command. Moreover, the bureaucracy employs a division of labor, under which work is separated into smaller tasks assigned to different people or groups.

EXAMPLE

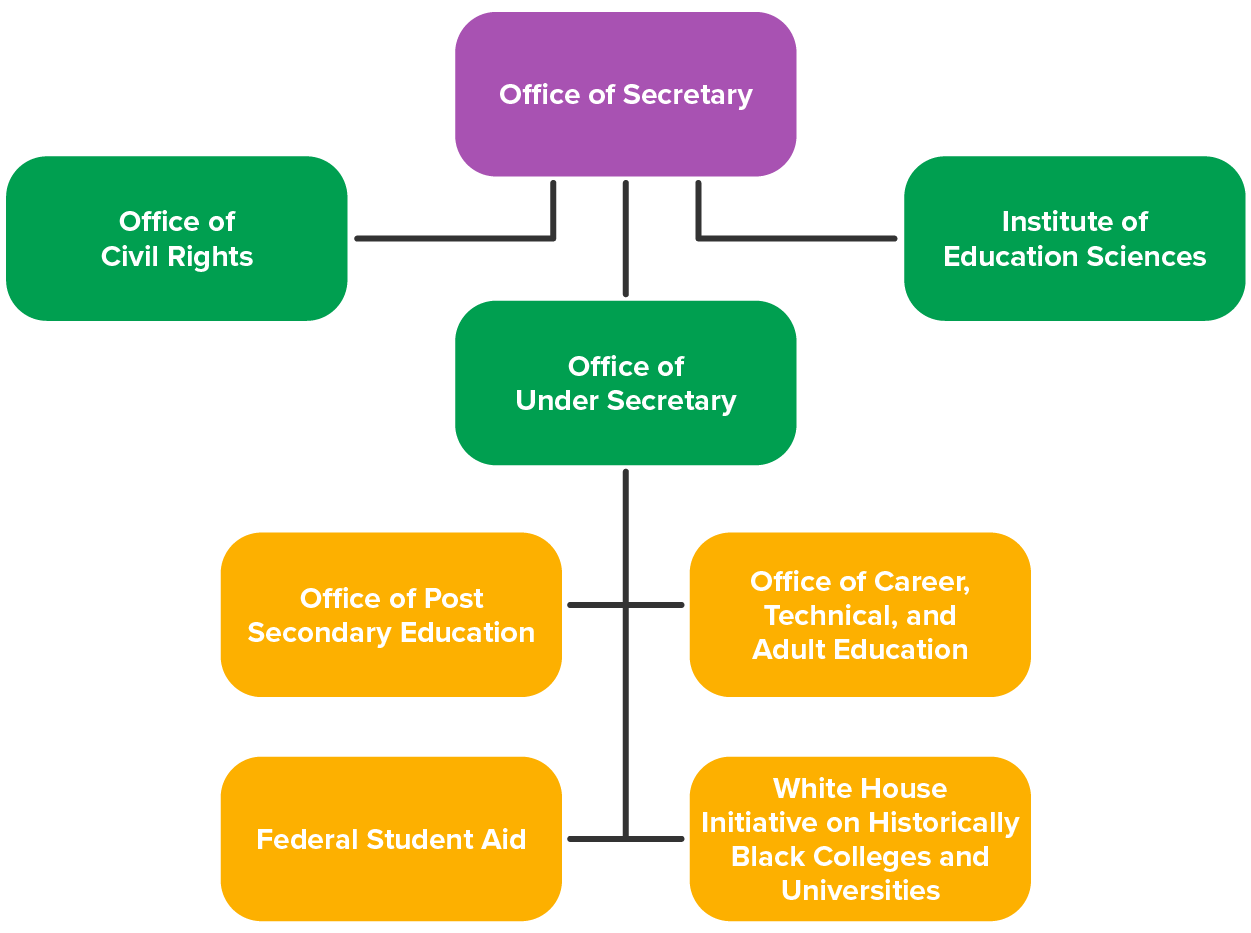

Consider the U.S. Department of Education part of the federal bureaucracy. Its overall mission is to promote student achievement and ensure equal access to education. Figure 1 shows a partial organizational chart of the department. The Office of Secretary is at the top of the chart, above three other offices. Authority and directions flow from the Office of Secretary to these three offices.

Bureaucracy is not unique to government. It is also found in the private and nonprofit sectors. Almost all organizations are bureaucratic—regardless of their scope and size—although public and private organizations differ in some important ways. For example, while private organizations are responsible to a superior authority such as an owner, board of directors, or shareholders, federal governmental organizations answer to the president, Congress, the courts, and ultimately the public.

The underlying goals of private and public organizations also differ. While private organizations seek to survive by controlling costs, increasing market share, and realizing a profit, public organizations find it more difficult to measure the elusive goal of operating with efficiency and effectiveness.

Bureaucracies tend to grow over time. In the early U.S. republic, the bureaucracy was quite small. This is understandable since the American Revolution was in large part a revolt against executive power and the British imperial administrative order. Nevertheless, while neither the word “bureaucracy” nor its synonyms appear in the text of the Constitution, the document does establish a few broad channels through which the emerging government could develop the necessary bureaucratic administration.

For example, Article II, Section 2, provides the president the power to appoint officers and department heads. In the following section, the president is further empowered to see that the laws are “faithfully executed.” More specifically, Article I, Section 8, empowers Congress to establish a post office, build roads, regulate commerce, coin money, and regulate the value of money, all of which require administrative bodies.

Granting the president and Congress such responsibilities appears to anticipate a bureaucracy of some size. Yet the design of the bureaucracy is not described, and it does not occupy its own section of the Constitution; the design and form were left to be established in practice.

Under President George Washington, the bureaucracy remained small but grew enough to accomplish the necessary tasks at hand. Washington’s tenure saw the creation of the Department of State to oversee international issues, the Department of the Treasury to control coinage, and the Department of War to administer the armed forces. The employees within these three departments, in addition to the growing postal service, constituted the majority of the federal bureaucracy for the first three decades of the republic (Figure 2).

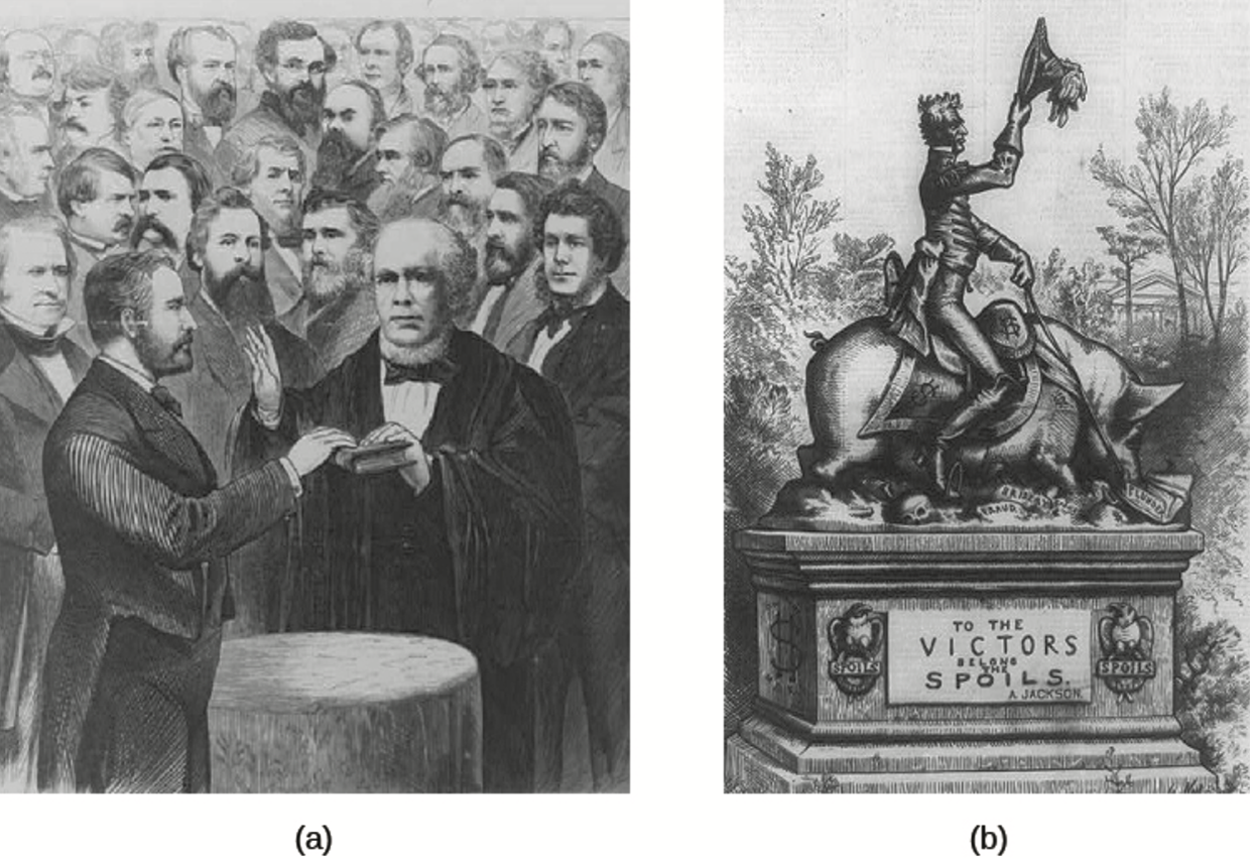

Several developments contributed to the growth of the bureaucracy from these humble beginnings. The first development was the rise of centralized party politics in the 1820s. Under President Andrew Jackson, many thousands of party loyalists filled the ranks of the bureaucratic offices around the country. This was the beginning of the spoils system, in which political appointments were transformed into political patronage doled out by the president on the basis of party loyalty.

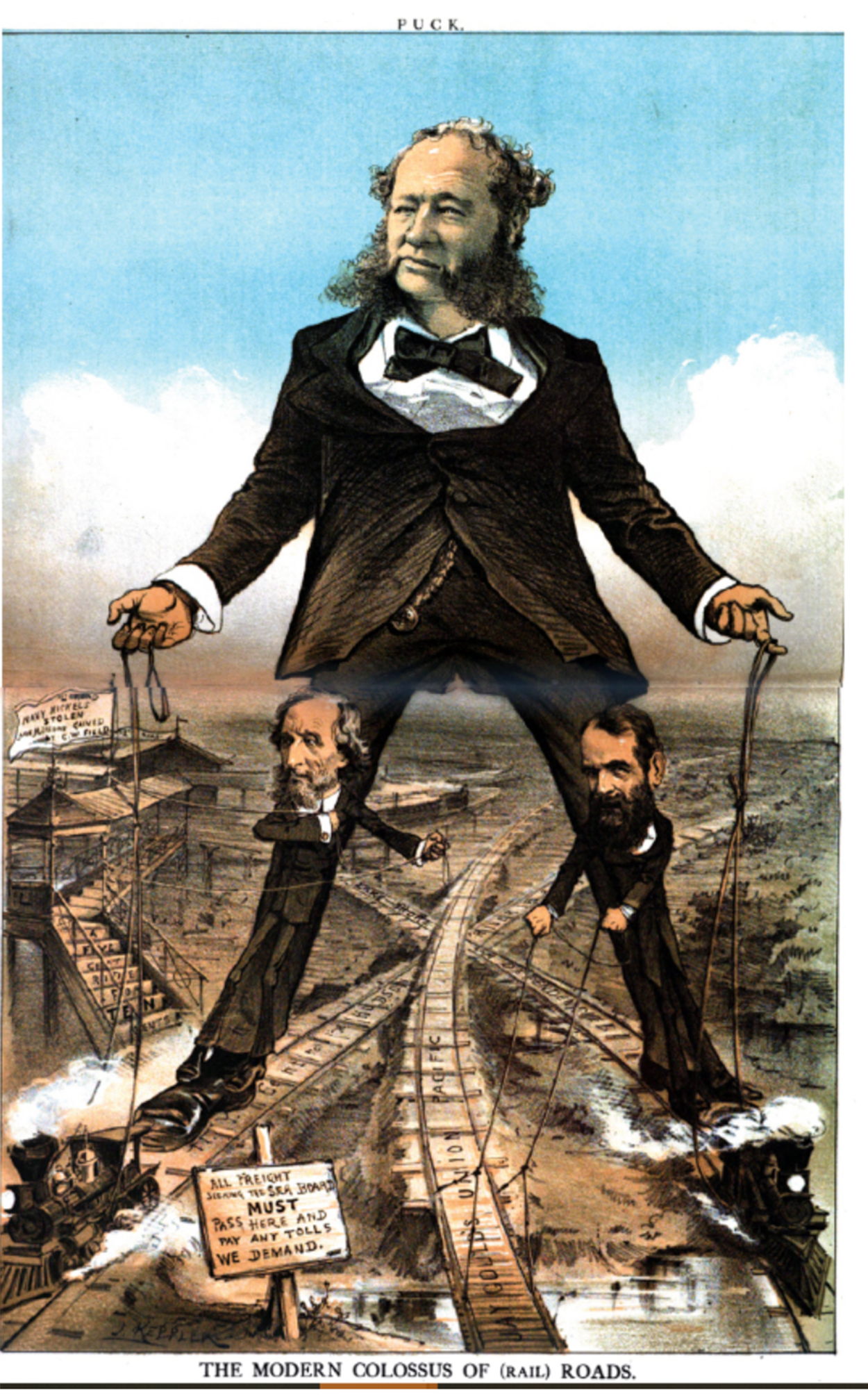

The second development was industrialization, which in the late nineteenth century significantly increased both the population and economic size of the United States. These changes in turn brought about urban growth in a number of places across the East and Midwest. Railroads and telegraph lines spread across the country. The government and its bureaucracy were closely involved in providing land to the western railways. Americans grew increasingly concerned about the power of railroad magnates to exploit small businesses and citizens (Figure 3).

As a result, government assumed a new function: the regulation of big businesses, such as railroads and oil, in the early twentieth century. Today, government regulations apply to almost every product you consume—including the temperature at which dried eggs should be stored at fast-food restaurants serving breakfast.

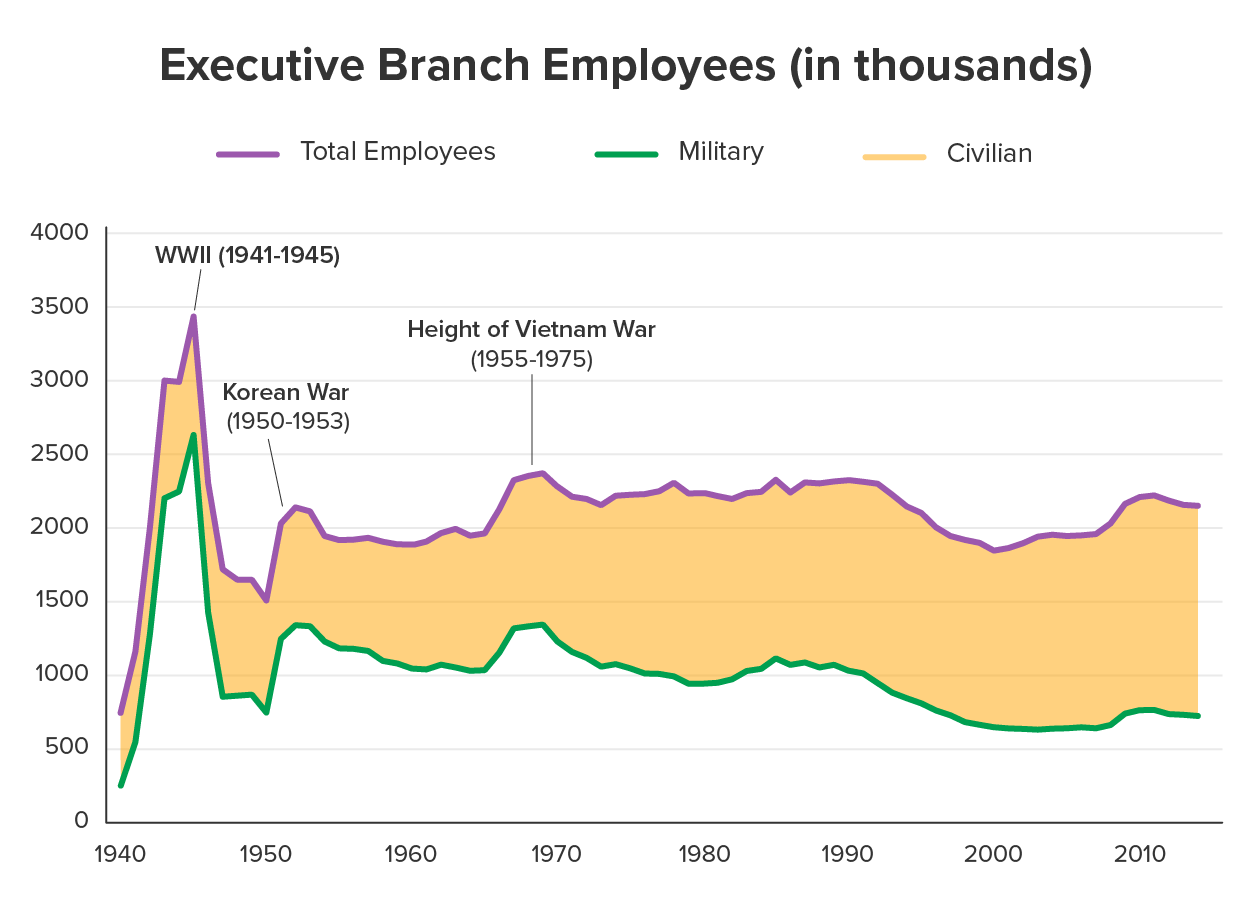

The next two periods of increased bureaucratic growth in the United States—the 1930s and the 1960s—did far more than expand the size of government. They created an economic safety net, known as the social welfare system, to assist the unemployed, the elderly, and others in need. Further, the bureaucracy expanded as the government began to regulate the medical and agricultural industries, among others. Wars also contributed to the swelling in the ranks of government employment (Figure 4).

To this day, controversy exists over whether this government expansion came with unacceptable economic costs.

Early in the nation’s bureaucracy, many jobs were filled by individuals who were political friends of the president or other elected officials through the spoils system. This system rewarded political supporters with paid positions in the U.S. government. It was assumed that the government would work far more efficiently if the key federal posts were occupied by those already supportive of the president and his policies. Patronage had the advantage of putting political loyalty to work, by making the government responsive to the electorate and keeping election turnout robust.

The number of federal posts the president sought to use as rewards for supporters swelled over the decades. Criticism of the spoils system grew, especially in the mid-1870s, after numerous scandals associated with the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant (Figure 6).

As the negative aspects of political patronage continued to infect bureaucracy in the late nineteenth century, calls for civil service reform grew louder. Those supporting the patronage system held that their positions were well earned; those who condemned it argued that federal legislation was needed to ensure jobs were awarded on the basis of merit.

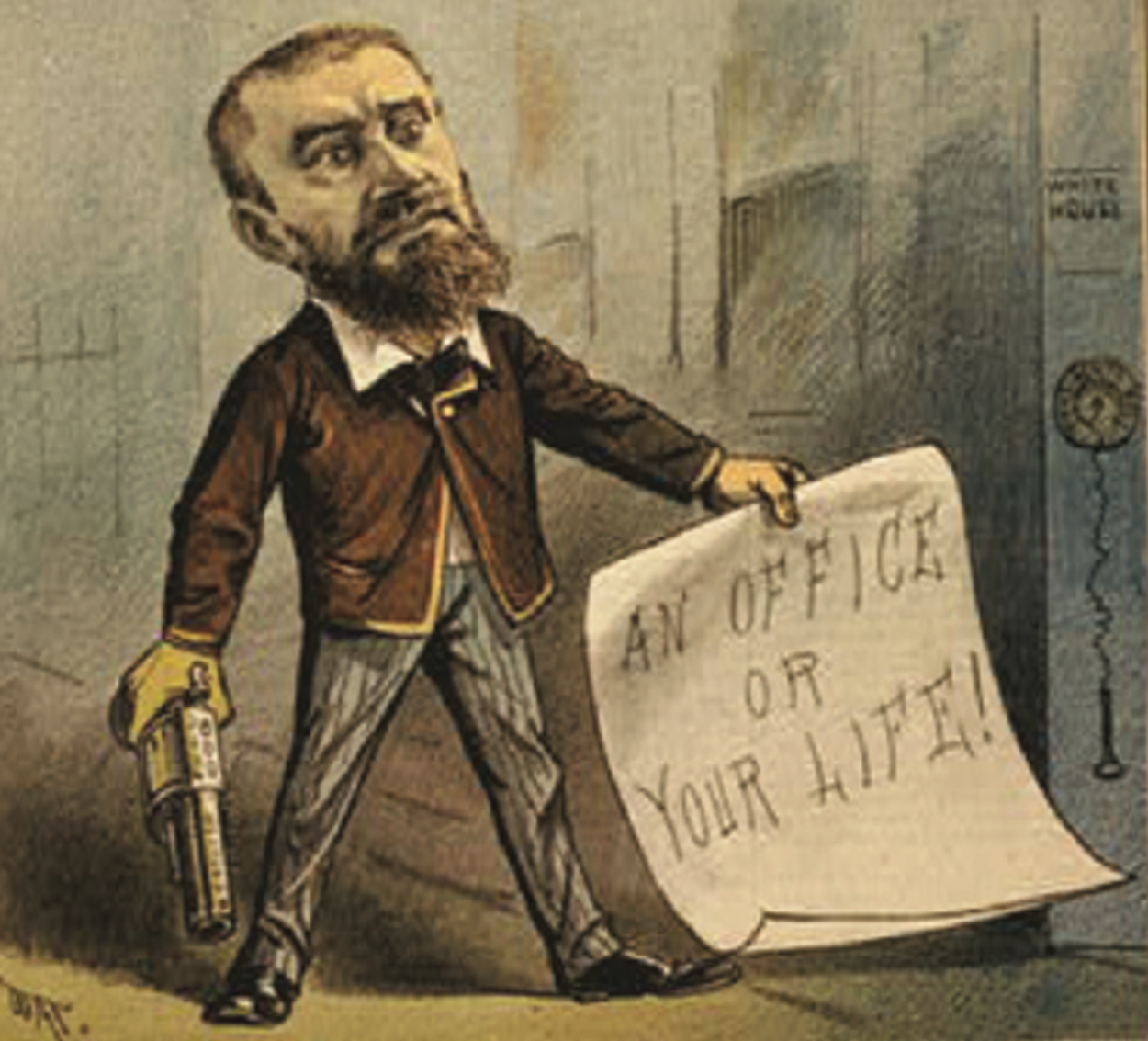

Eventually, after President James Garfield was assassinated by a disappointed office seeker (Figure 7), Congress responded to cries for reform with the Pendleton Act of 1883, also called the Civil Service Reform Act.

The Pendleton Act established the foundations for the merit system that emerged in the decades that followed. Three elements of the law stand out as especially significant.

In 1883, civil servants under the control of the commission amounted to about 10 percent of the entire government workforce. However, over the next few decades, this percentage increased dramatically.

The effects of both the law and the increase in the size of the civil service were huge for the government. Presidents and representatives were no longer spending their days doling out or terminating appointments. Consequently, many members of the civil service could no longer count on their political patrons for job security.

As the size of the federal government and its bureaucracy grew following the Great Depression, many became increasingly concerned that the Pendleton Act prohibitions on making civil service employment conditional upon political activity were no longer strong enough.

As a result of these mounting concerns, Congress passed the Hatch Act of 1939—or the Political Activities Act. The main provision of this legislation prohibits bureaucrats from actively engaging in political campaigns and from using their federal authority via bureaucratic rank to influence the outcomes of nominations and elections.

Reform pressure arose again in the late 1970s as the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal prompted the public to a fever pitch of skepticism about government itself. Congress and the president responded with the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, which abolished the Civil Service Commission.

In its place, the law created two new federal agencies: the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). The OPM has the responsibility for recruiting, interviewing, and testing potential government employees in order to choose those who should be hired. The MSPB is responsible for investigating charges of agency wrongdoing and hearing appeals when corrective actions are ordered. Together these new federal agencies were intended to correct perceived and real problems with the merit system, protect employees from managerial abuse, and generally make the bureaucracy more efficient and more demographically representative of the American people (Figure 8).

Many years ago, the merit system would have required all applicants to also test well on a civil service exam, as was stipulated by the Pendleton Act. This mandatory testing has since been abandoned, and now approximately eighty-five percent of all federal government jobs are filled through an examination of the applicant’s education, background, knowledge, skills, abilities, and specialized civil service tests.

Civil service exams are still required for some applicants to demonstrate broad critical thinking skills, such as those pursuing foreign service jobs. More often, however, these exams are required for positions demanding specific or technical knowledge, such as customs officials, air traffic controllers, and federal law enforcement officers. Additionally, new online tests are increasingly being used to screen the ever-growing pool of applicants.

Civil service exams also currently test for skills applicable to clerical workers, postal service workers, military personnel, health and social workers, and accounting and engineering employees, among others. Applicants with the highest scores on these tests are most likely to be hired for the desired position. Like all organizations, bureaucracies must make thoughtful investments in human capital. And even after hiring people, they must continue to train and develop them to reap the investment they make during the hiring process.

Today, those interested in federal jobs can visit www.usajobs.gov, a website created by the OPM to assist job seekers looking for employment with the federal government.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “AMERICAN GOVERNMENT 3E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/AMERICAN-GOVERNMENT-3E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.