Table of Contents |

Lifespan development involves the exploration of the biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and constancies that occur throughout the course of life. Though lifespan development has been presented as a theoretical perspective, proposing several fundamental, theoretical, and methodological principles about the nature of human development, an attempt by researchers has been made to examine whether research on the nature of development suggests a specific metatheoretical worldview. Several beliefs, taken together, form the “family of perspectives” that contribute to this particular view.

German psychologist Paul Baltes, a leading expert on lifespan development and aging, developed an approach to studying development called the lifespan perspective. This approach is based on six key principles:

Lifelong development means that development is not completed in infancy, childhood, nor at any other specific age. Instead, it encompasses the entire lifespan, from conception to death. The study of development traditionally focused almost exclusively on the changes occurring from conception to adolescence, as well as the gradual decline in old age. Previously, it was believed that the 5 or 6 decades after adolescence yielded little to no developmental change. The current view reflects the possibility that specific changes in development can occur later in life, without having been established at birth. The early events of one’s childhood can be transformed by later events in one’s life. This belief clearly emphasizes that all stages of the lifespan contribute to human development.

Many diverse patterns of change, such as direction, timing, and order, can vary among individuals, and they affect the ways in which people develop. For example, the developmental timing of events can affect individuals in different ways because of their current level of maturity and understanding. As individuals move through life, they are faced with many challenges, opportunities, and situations that impact their development. Remembering that development is a lifelong process helps us gain a wider perspective on the meaning and impact of events throughout life.

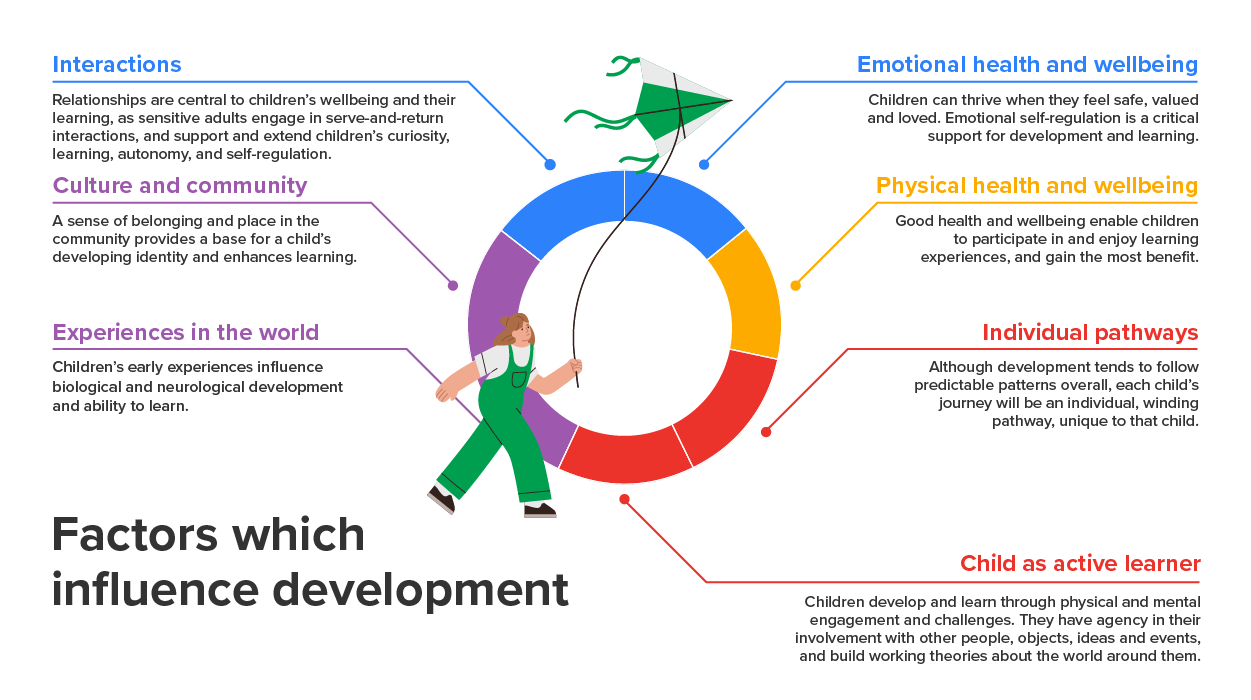

By multidimensionality, Baltes is referring to the fact that a complex interplay of factors influence development across the lifespan, including biological (of and related to the natural processes of living things, like genetics), cognitive (of and related to mental and thinking processes), and socioemotional (of and related to one’s social and emotional health and well-being, such as understanding feelings, peer relationships, and relating to others). Baltes argues that a dynamic interaction of these factors is what influences an individual’s development. Individuals do not exist separate from other living and nonliving things; we interact with our environments to varying degrees, which impacts our developmental trajectory.

EXAMPLE

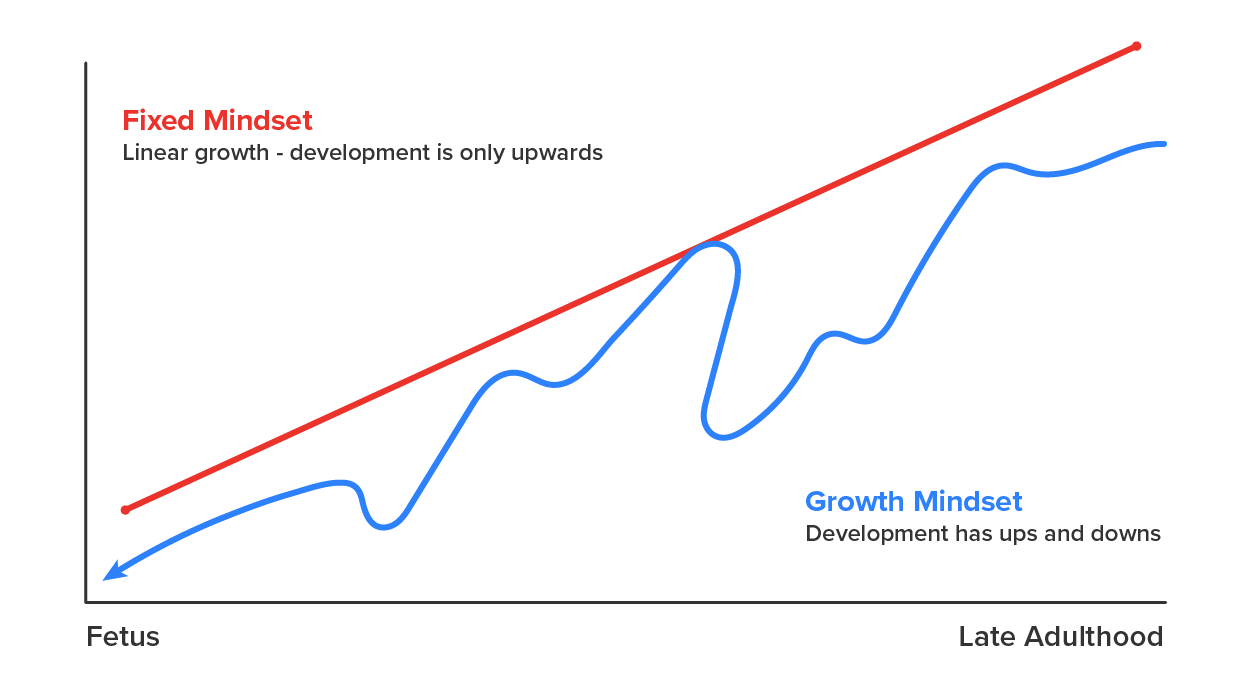

Many of us have heard that the first 5 years of an individual’s life is a critical developmental period. This is in part because of the tremendous amount of brain development during this time. The experiences and interactions a child has with others in their environment, whether they are positive, negative, or neutral, will impact the way the child perceives the world around them. Their language, communication, and social skills will develop, each of which will further be impacted by the environment(s) they are exposed to (e.g., home, school, daycare). This itself highlights the multidimensional nature of development, as it is not restricted to a single domain but rather an interaction across all domains.Baltes states that the development of a particular domain does not occur in a strictly linear fashion, but that development of certain traits can be characterized as having the capacity for both an increase and decrease in efficacy over the course of an individual’s life, which is multidirectional development. We can also understand this from a fixed mindset versus a growth mindset lens, where development across the lifespan progresses upward without fluctuations (fixed mindset), or development has ups and downs that are affected by and further impact developmental outcomes throughout life (growth mindset). If we use the example of puberty, we can see that certain domains may improve or decline in effectiveness during this time, which reflects the growth mindset approach to development.

EXAMPLE

Self-regulation (of and related to one’s ability to understand and manage an individual’s behaviors, reactions, and thoughts, such as emotions, sleep, and eating) is one domain of puberty which undergoes profound multidirectional changes during the adolescent period. During childhood, individuals display difficulties in effectively regulating their actions, emotions, and behaviors, which may lead them to behave without considering the consequences. Neuronal changes during puberty, however, help individuals to begin regulating their emotions and impulses. This is done through changes in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, as well as the limbic system, which lead to enhanced self-regulation skills. These neuronal connections do not stop at puberty and will continue to develop.

Plasticity denotes intrapersonal variability, and it focuses heavily on the potentials and limits of the nature of human development. The notion of plasticity emphasizes that there are many possible developmental outcomes, and that the nature of human development is much more open and pluralistic than originally implied by many traditional views. There is no single pathway that must be taken in an individual’s development across the lifespan. Plasticity is imperative to current research, because the potential for intervention is derived from the notion of plasticity in development. Undesired development or behaviors could potentially be prevented or changed.

In Baltes’s theory, the paradigm of contextualism refers to the idea that three systems of biological and environmental influences work together to influence development. Development occurs in context and varies from person to person, depending on factors such as a person’s biology, family, school, church, profession, nationality, and ethnicity. Baltes identified three types of influences that operate throughout the life course:

IN CONTEXT

Normative age-graded influences are those biological and environmental factors that have a strong correlation with chronological age, such as puberty or menopause, or age-based social practices, such as beginning school or entering retirement. Normative history-graded influences are associated with a specific time period that defines the broader environmental and cultural context in which an individual develops. For example, development and identity are influenced by historical events of the people who experience them, such as the Great Depression, WWII, Vietnam, the Cold War, the War on Terror, or advances in technology.

Nonnormative influences are unpredictable and not tied to a certain developmental time in a person’s development or to a historical period. They are the unique experiences of an individual, whether biological or environmental, that shape the development process. These could include milestones like attending a higher educational institution, earning a master’s degree, or getting a certain job offer, or other life events such as going through a divorce or coping with the death of a loved one.

Any single discipline’s account of development across the lifespan would not be able to express all aspects of this theoretical framework. That is why it is suggested explicitly by lifespan researchers that a combination of disciplines is necessary to understand development. Multidisciplinary is understanding development from multiple disciplines, rather than from a single discipline. Psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, anthropologists, educators, economists, historians, medical researchers, and others may all be interested and involved in research related to the normative age-graded, normative history-graded, and nonnormative influences that help shape development. Many disciplines are able to contribute important concepts that integrate knowledge, which may ultimately result in the formation of a new and enriched understanding of development across the lifespan.

Culture is a broad term that encompasses beliefs, ideas, and practices about what is right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, as well as what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance, because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations. Culture is learned from parents, schools, churches, media, friends, and others over the course of a lifetime. The kinds of traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture serve to help members function in their own society and to value their own society.

So much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and can be difficult to apply in various cultural contexts. For example, Erikson’s theory that teenagers struggle with identity assumes that all teenagers live in a society in which they have many options and must make an individual choice about their future. In many parts of the world, one’s identity is determined by family status or society’s dictates. In other words, an individual has no choice, as this aspect of their identity is predetermined.

Even the most biological events can be viewed in cultural contexts that are extremely varied. Consider two very different cultural responses to menstruation in young girls.

In some cultures, there are mythical tales surrounding menstruation, while in others, menstruation is believed to be impure, unclean, and a problem. When the latter happens, women are ostracized from everyone, including family, friends, co-workers, and loved ones, as anything that they touch is also considered impure.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING'S LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Tan, D. A., Haththotuwa, R., & Fraser, I. S. (2017). Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 40, 121-133.