Table of Contents |

The origins of conflict between the British, French, and Native Americans in North America during the 17th and 18th centuries are best understood by considering the effects of three forces: population growth, speculation in western lands, and geopolitical rivalry between France and Great Britain.

In North America, population increases in the colonies created a shortage of land along the coast, which prompted thousands of settlers to move toward the Appalachian Mountains in search of new land. From a population of 250,000 people in 1700, the English colonial population (excluding enslaved persons) had increased to 1.2 million people by 1750. The population rose to at least 1.5 million people by 1760.

Speculators, backed by capital provided by London and by colonial investors, sought to profit from population growth and increased demand for western lands by claiming territory that was not theirs to own. For example, the Ohio Land Company (organized in 1747), claimed half a million acres in the Ohio River Valley. In doing so, the company ignored the fact that the French and a number of Native American tribes also claimed this territory. Similarly, the Susquehanna Land Company claimed hundreds of thousands of acres in northern Pennsylvania, including land already claimed by the Iroquois Confederacy.

Population growth and rampant speculation in western lands combined with persistent geopolitical rivalry between France and England. While colonial land speculators claimed acreage in the Ohio River Valley, British and French diplomats sought alliances with Native American tribes to gain control of the area. Access to valuable commodities such as furs depended on their success in these negotiations. Geopolitical positioning was also at stake; the British recognized that they could separate French Canada from French Louisiana if they controlled the Ohio River Valley. Of course, this was unacceptable to the French.

These three forces were the product of several indecisive imperial conflicts between Great Britain and France that occurred during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. These conflicts had American and European fronts, which produced two names for each war.

EXAMPLE

Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713) is also known as the War of Spanish Succession.During this war, England fought against Spain and France to determine who would be the next monarch of Spain. In North America, fighting took place in Florida, where South Carolinians allied themselves with the Yamasee to attack the Spanish and their Native American allies. To the North, the British succeeded in conquering Acadia and Newfoundland (see map above), but failed to take Quebec, which would have given them complete control of Canada.

As a result of imperial conflicts such as Queen Anne’s War, generations of British colonists grew up during a time when much of North America was engaged in war. Many colonists and Native Americans experienced these conflicts firsthand, especially in those middle grounds where colonists and native peoples often crossed paths.

As British speculators, settlers, and traders continued to flood into the Ohio River Valley, the French responded by building a series of forts and convincing a number of Native American tribes to go to war against the English. These tribes included the Delawares, Shawnees, and members of the Iroquois Confederacy. By 1754, the French drove English traders out of the Ohio River Valley with assistance from their Native American allies. The French established themselves as far east as present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where, at Fort Duquesne, they defeated an ambitious young colonel named George Washington.

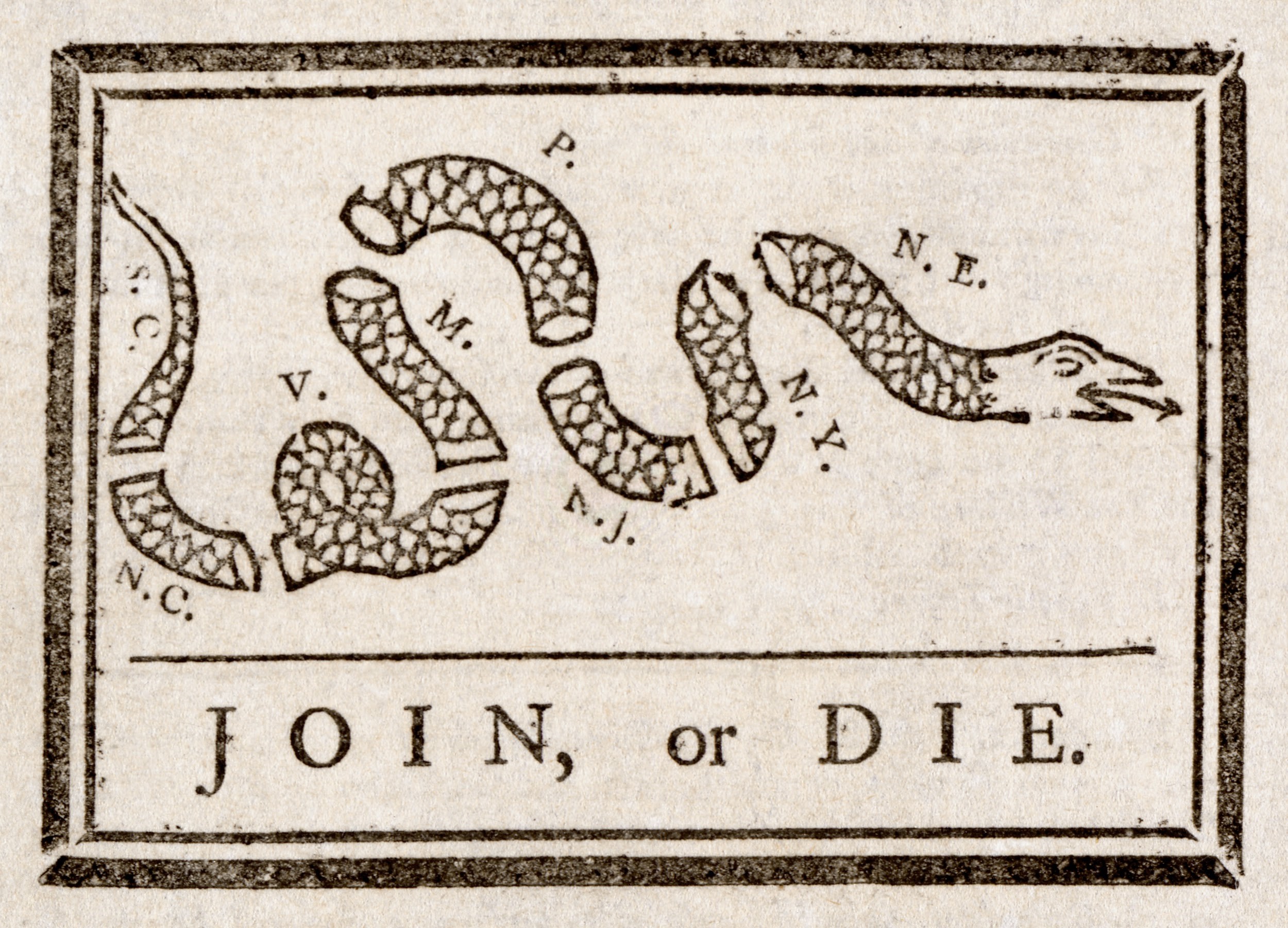

Immediately following Washington’s defeat, colonists attempted to centralize and coordinate their efforts against the French, but they were unable to overcome their internal divisions. This problem was evident in 1754, when the Albany Plan of Union—an attempt by the colonies to unify for military purposes, proposed at the Albany Congress—failed to be adopted.

A key element of the Albany Congress’s unification effort lay in convincing the Iroquois to join the struggle on the side of the British. Yet, while representatives from the Congress and the Iroquois met in Albany, land speculators from Connecticut and Pennsylvania conspired with other Iroquois chiefs to purchase lands west of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. The Iroquois leadership did not sanction the deal, and negotiations between the tribes and the Albany Congress faltered. In addition, the Plan of Union was rejected by colonial legislatures and the Crown.

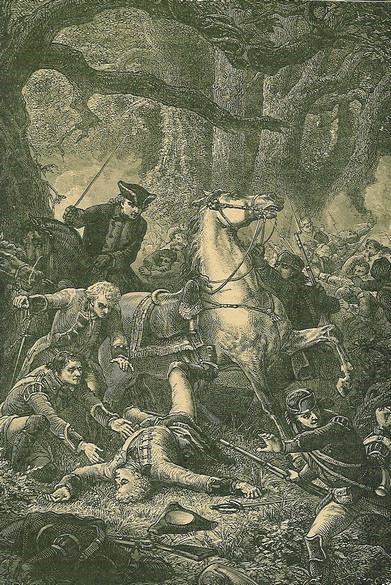

The war went horribly for the British at first. In 1755, Braddock moved on Fort Duquesne with about 2,200 troops. Twenty miles from the fort, Braddock's force was ambushed by the French and their Native American allies. Approximately two thirds of Braddock's men (including Braddock himself) were killed. George Washington, who was Braddock's aide-de-camp, saved the remaining troops in a retreat across the Appalachian Mountains.

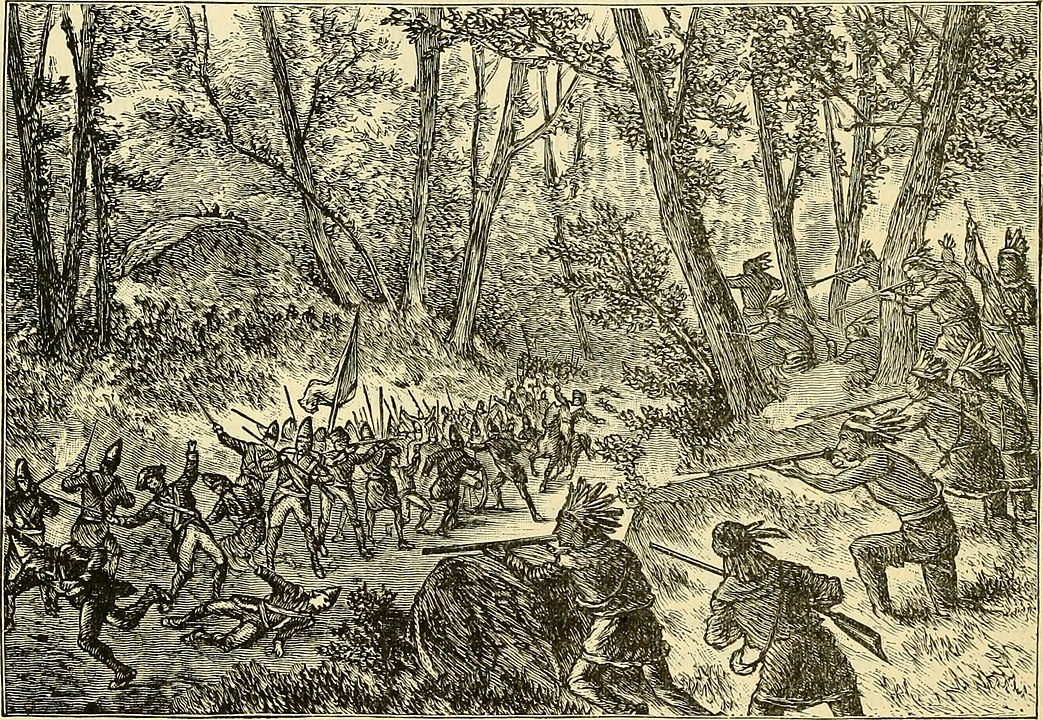

Subsequent victories by the French, combined with Native American raids across the backcountry, placed the colonies in a panic by 1757. Indeed, the backcountry erupted in violence between colonists and Native Americans during the war.

From the Native American perspective, there was a reason for the violence. For tribes such as the Delaware, Shawnee, and Iroquois, the targets were specific—Euro-American immigrants who ignored native land claims or had sold land that did not belong to them. The Native Americans often attacked people against whom they had personal resentments and explained their reasoning before executing settlers or taking them captive.

Colonists returned the violence in kind, but they did so in a less focused manner; they were satisfied with killing Native Americans indiscriminately. Accounts of violence during the French and Indian War include descriptions of settlers scalping native women and children or desecrating corpses. The settlers believed they were justly taking revenge for what the Native Americans had done to their neighbors and kin. Persistent and bloody racial violence between Native Americans and colonists was tearing the backcountry apart.

The ascent of William Pitt in London as the secretary of state turned the tide for Great Britain after 1757. Pitt was determined to wage an all-out war against the French, and he shifted the British Empire's military resources toward North America, which he saw as the key to global victory. He sent new generals and additional troops, and spent a massive amount of money, borrowing up to one million pounds for the war effort.

With Pitt's ascension, the French and Indian War became a conflict between two rival empires, their European-style armies, and their colonial populations, rather than a war between Native Americans and colonists. The French stood little chance in this type of conflict, which pitted them against the wealth and manpower of the British Empire. There were roughly 70,000 French Americans in New France by this time, but only a fraction of them were available for military service. Of the nearly 1.5 million colonists in British North America, 50,000 turned out for military campaigns in 1758. This numerical advantage turned the tide in favor of the British, as the timeline below shows:

| Year | British Wins |

|---|---|

| 1758 | British took Louisbourg, effectively cutting off New France from trade within the Atlantic Ocean. British Forces took Fort Ticonderoga, setting the stage for an invasion of Canada. |

| 1759 | British took Quebec (the capital of New France). |

| 1760 | British took Montreal. |

| 1761 | Conflict between Great Britain and France in North America ends, with Great Britain having gained control of Canada and the Ohio River Valley; war continues in Europe and elsewhere. |

| 1762 | Spain joins the conflict against Britain. |

| 1763 | British makes gains in Caribbean, Gibraltar, India, and the Philippines; Treaty of Paris signed. |

American colonists were ecstatic upon the war's end because they were now members of the world's most powerful empire; one that vanquished the French in North America. The image below provides a breakdown of the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1763), showing what France, Spain, and Great Britain gained and lost as a result of the war.

| Gains for France | Gains for Britain | Gains for Spain |

|---|---|---|

| Gained Caribbean Islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique from Britain |

Gained Canada from France. Gained all French claims east of the Mississippi River (Ohio River valley) Gained Florida from Spain |

Gained all French claims West of the Mississippi River (Louisiana) Gained Cuba and the Philippines from Britain |

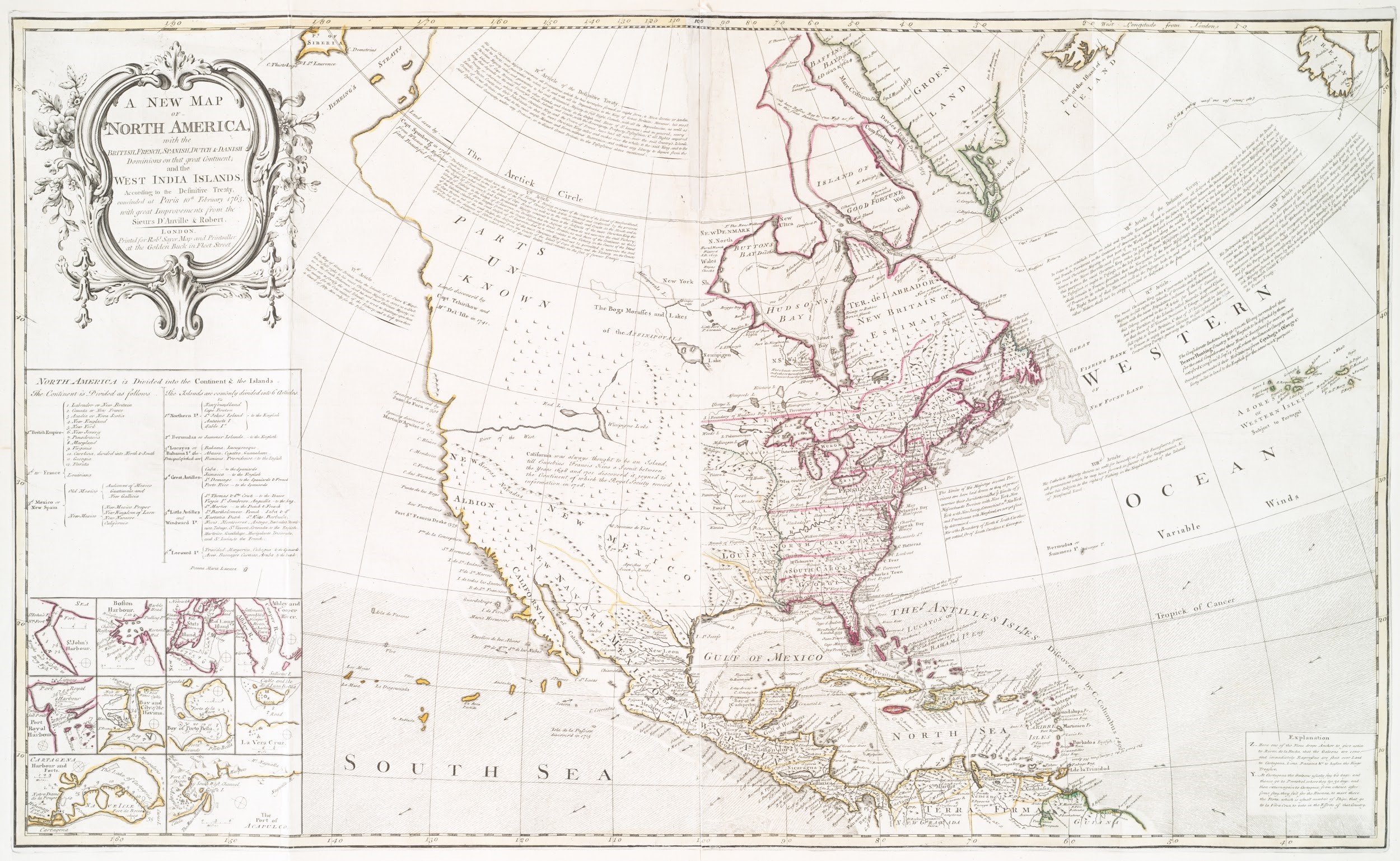

Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris, all of North America east of the Mississippi River was now in British hands. The map below, published after the Treaty of Paris, made this point clear.

Upon the end of the French and Indian War, Great Britain secured its claims to all of eastern North America. This map, published shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, highlights British claims in red. Spanish claims, which included all of North America west of the Mississippi River, are highlighted in yellow.

American colonists saw some problems with the peace, however:

The reminiscences of Gibson Clough provide a glimpse of the tensions between British regulars and American militia during the war. Clough enlisted in the militia in 1759 and took part in military operations in Canada. The excerpt below (Essex Institute Historical Collections, 1993), displays Clough’s enthusiasm for fighting against the French on behalf of the Crown, but also provides evidence that the militia chafed against British army discipline.

Reminiscences of Gibson Clough, American Militia

"I was born in Salem in New England in ye year 1738, in June the 22 and I lived with my father until that I was almost one and twenty years of age and I was brought up very carefully and tenderly by my parents and they to me gave common learning as is usual for parents to do by children under their Care and as there had been war between the Crown of England and France by which reason men was very hard for to be raised in New England, I then willingly enlisted in the service of my King and Country in the then intended expedition against Canada, in Capt. Andrew Giddings Company in a provincial Regiment Commanded by Coll Jonathan Bagley Esqr in the year 1759…

And so we stayed all winter [1759-1760], which was hard as we were only enlisted for six months by a proclamation issued forth by his Excellency Thomas Pownall ye Governor ; and as was said we were to be dismissed by the first of November or as much sooner as his majesty’s service would admit….

(January 11) One Hager of our Regiment was whipped thirty stripes for disobedience of orders….

January 28th. A drummer belonging to Warburton’s Regiment was shot for breaking into a house and stealing a box of Soap, and for other offences he had committed, and also a private Soldier was condemned to die with him; but after having come to the place of execution, he was reprieved by the intercession of one Capt. Johnson for him. The drummer’s name was Conrey, and the other was Johnson, ye latter reprieved, also three more are to receive other punishment as whipping, the one is to have one thousand lashes, and the other two five hundred each. The aforesaid had their last trial at a general Court Martial on the 19th instant….

April 1 (1760). I enlisted again for ye ensuing campaign against Canada…"

Note: Clough returned to Salem in January 1761.

The above entry shows that Clough originally enlisted for a 6-month term, only to discover that his term in the service would last longer than he expected. Clough’s regiment ended up at Fort Louisbourg, a fort situated on the coast of Nova Scotia captured by the British in 1758. While occupying the fort, militia units such as Clough’s were subject to British military discipline and transgressors were punished severely.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Essex Institute historical collections : Essex Institute. (1993). Retrieved January 20, 2017, from archive.org/details/essexinstitutehi03esseuoft/page/4/mode/2up