Table of Contents |

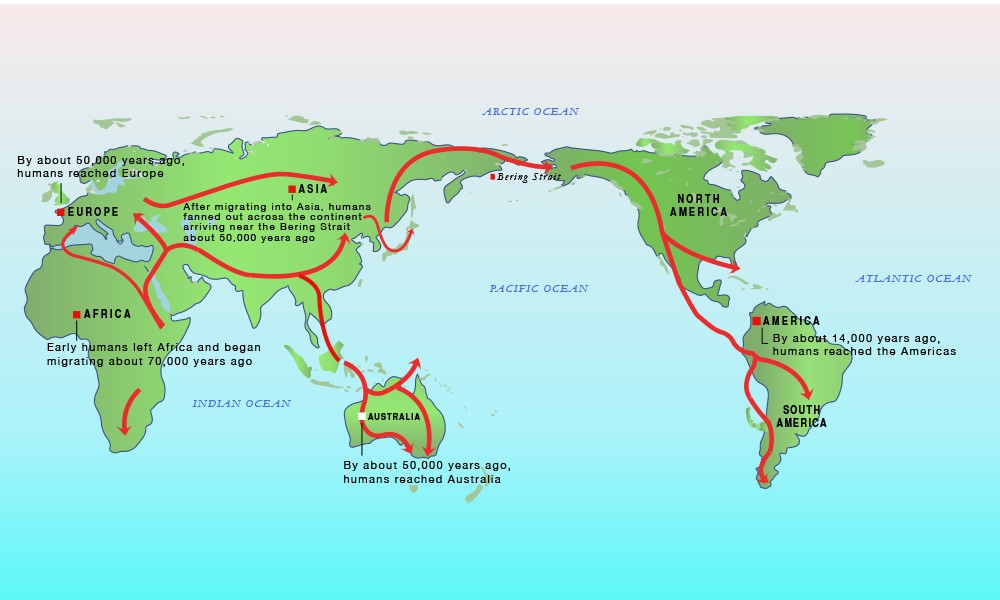

Between 9 and 15,000 years ago, some scholars believe that a land bridge, now called Beringia, existed in the Bering Strait between present-day Russia and Alaska. The first human inhabitants of what would be named the Americas migrated across this bridge in search of food. The Bering Strait was formed when the glaciers melted, and water engulfed Beringia. Later settlers came by boat across the narrow strait.

As they moved southward, the settlers eventually populated both North and South America. These settlers created unique cultures that ranged from the highly complex and urban Aztec civilization, in what is now Mexico City, to the woodland tribes of Eastern North America. Recent research suggested that migrant populations may have traveled down the West coast of South America by water as well as by land.

Researchers believe that about 10,000 years ago, humans began the domestication of plants and animals and added agriculture, as a means of sustenance, to hunting and gathering techniques. With the agricultural revolution and the more abundant and reliable food supplies it brought, populations grew. People developed a more settled way of life and built permanent settlements. Nowhere in the Americas was this more obvious than in Mesoamerica.

Mesoamerica cradled a number of civilizations with similar characteristics, although they were marked by great topographic, linguistic, and cultural diversity. Mesoamericans were polytheistic; their gods possessed both masculine and feminine traits and demanded blood sacrifices of enemies taken in battle (i.e., ritual bloodletting).

Corn, or maize, formed the basis of Mesoamerican diets. They developed a mathematical system, built huge edifices, and devised a calendar that accurately predicted eclipses and solstices. Priest-astronomers used the calendar to direct the planting and harvesting of crops. Most importantly, they created the only known written language in the Western Hemisphere. Researchers have made much progress in interpreting the inscriptions on their temples and pyramids. Though the area had no overarching political structure, trade across long distances helped diffuse culture. Commerce was based on weapons made of obsidian, jewelry crafted from jade, feathers woven into clothing and ornaments, and cacao beans that were whipped into a chocolate drink.

The mother of Mesoamerican civilizations was the Olmec civilization. The Olmecs worshipped a rain god, a maize god, and the feathered serpent that became important in the future pantheons of the Aztecs and the Maya. The Olmecs also developed a system of trade throughout Mesoamerica, which produced an elite class. Although no one knows what happened to the Olmecs after about 400 B.C.E., in part because the jungle reclaimed many of their cities, their culture was the basis for the Maya and the Aztecs.

The Maya civilization became one of the most powerful empires in Mesoamerica and flourished from roughly 2,000 B.C.E. to 900 C.E. in present-day Mexico, Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala. The Mayan architectural and mathematical contributions were significant. Not only did their influence and reach extend beyond that of the Olmecs but they also perfected the calendar and the written language the Olmecs originated. They devised a written mathematical system to record crop yields and population and to assist in trade.

Surrounded by farms relying on primitive agriculture, they built the city-states of Copán, Tikal, and Chichén Itzá along their major trade networks. The Maya also constructed temples, statues of gods, pyramids, and astronomical observatories.

Alongside the rise of the Mayan city-states, a city known as Teotihuacán emerged in the fertile central highlands of Mesoamerica. Teotihuacán was located about 30 miles northeast of modern Mexico City, was one of the largest population centers in pre-Columbian America, and was home to more than 100,000 people at its height in about 500 C.E.

Large-scale agriculture and the resultant abundance of food allowed time for people to develop special trades and skills other than farming. Builders constructed over 2,200 apartment compounds for multiple families, as well as more than 100 temples. Near the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, graves have been uncovered that suggest humans were sacrificed for religious purposes. The city was also the center for trade, which extended to settlements on the Gulf Coast of Mesoamerica.

The Mayans were a Mesoamerican culture with strong ties to Teotihuacán. However, Mayan civilization declined by about 900 C.E. because of poor soil and a drought that lasted nearly two centuries. As a consequence, the large population centers were abandoned. The Spanish found little organized resistance among the Maya upon their arrival in the 1520s.

Hernán Cortés, the Spaniard, arrived on the coast of Mexico in 1519 at the site of present-day Veracruz. He heard of a great city known as Tenochtitlán ruled by an emperor named Moctezuma. This city was tremendously wealthy—filled with gold—and took in tribute from surrounding tribes. The sheer number of people living within the city combined with the riches that Cortés found when he arrived were far beyond anything he or his men had ever seen.

According to legend, a warlike people called the Aztecs had left a city called Aztlán and traveled south to the site of present-day Mexico City. In 1325, they began construction of Tenochtitlán on an island in Lake Texcoco. When Cortés arrived in 1519, this settlement contained more than 200,000 inhabitants. It was the largest city in the Western Hemisphere at that time and was probably larger than any European city.

The Aztecs emigrated to the Central Valley of Mexico from the north in the 12th century and made use of swiftly organized political alliances to gain control of the region. Religion functioned as a central part of their social and political structure, which produced the construction of complex and elaborate temples within Tenochtitlán. Each god in the Aztec pantheon represented and ruled an aspect of the natural world, The gods represented aspects such as the heavens, farming, rain, fertility, sacrifice, and combat.

In South America, the most highly developed and complex society was that of the Inca. The Inca Empire, at its height in the 15th and 16th centuries, extended 2,500 miles. It was located on the Pacific coast and straddled the Andes Mountains from modern-day Colombia in the north to Chile in the south.

The Incan road system rivaled that of the Romans and efficiently connected the sprawling empire. The Inca, like all other pre-Columbian societies, did not use axle-mounted wheels for transportation. They built stepped roads to ascend and descend the steep slopes of the Andes. These would have been impractical for wheeled vehicles but worked well for pedestrians. These roads enabled the rapid movement of the highly trained Incan army. Runners called chasquis traversed the roads in a continuous relay system, which ensured quick communication over long distances. The Inca had no system of writing, however. They communicated and kept records using a system called the quipu.

The Inca farmed corn, beans, squash, quinoa, and the indigenous potato on terraced land they hacked from the steep mountains. Peasants received only one third of their crops for themselves. The Inca ruler required a third and a third was set aside in a welfare system for those unable to work.

The Inca worshipped the sun god Inti and called gold the “sweat” of the sun. Unlike the Maya and the Aztecs, they rarely practiced human sacrifice and usually offered the gods food, clothing, and coca leaves. They resorted to sacrificing prisoners in times of dire emergency, however, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes, volcanoes, or crop failure. The ultimate sacrifice was children who were specially selected and well-fed. The Inca believed these children would immediately go to a much better afterlife.

In 1911, the American historian Hiram Bingham uncovered the lost Incan city of Machu Picchu. The city is located about 50 miles northwest of Cusco, Peru. The city had been built in 1450 and inexplicably abandoned roughly 100 years later. Scholars believe the city was used for religious ceremonial purposes and housed priests. The Inca constructed walls and buildings of polished stones using only the strength of human labor and no machines. Some stones weighed over 50 tons but were fitted together perfectly without the use of mortar. In 1983, UNESCO designated the ruined city a World Heritage Site.

The North American native cultures were much more widely dispersed than the Mayan, Aztec, and Incan societies, with few exceptions. They were not as populous, nor did they have organized social structures like their neighbors in the south did. A few cultures had evolved into relatively complex forms, but they were already in decline at the time of Christopher Columbus’ arrival.

In the southwestern parts of the United States, several groups collectively called the Pueblo dwelled. The Spanish first gave them this name, which means “town” or “village.” They lived in towns or villages of permanent stone-and-mud buildings with thatched roofs. Like present-day apartment houses, these buildings had multiple stories, each with multiple rooms. The three main groups of the Pueblo people were the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi.

Roads that extended some 180 miles connected the Pueblos’ smaller urban centers to each other and to Chaco Canyon. Chaco Canyon had become the administrative, religious, and cultural center of their civilization by 1050 C.E. A century later, however, the Pueblo peoples abandoned their cities, probably because of drought. Their present-day descendants include the Hopi and Zuni tribes.

North American Indian groups that lived in the present-day Ohio River Valley and achieved their cultural apex from 1 C.E. to 400 C.E. are collectively known as the Hopewell culture. Their settlements were small hamlets unlike those of the southwest. They lived in wattle-and-daub houses (made from woven lattice branches daubed with wet mud, clay, or sand and straw). The Hopewell culture practiced agriculture, which they supplemented by hunting and fishing. They developed trade routes stretching from Canada to Louisiana by utilizing waterways; they exchanged goods with other tribes and negotiated in many different languages. From the coast, they received shells; from Canada, copper; and from the Rocky Mountains, obsidian. With these materials, they created necklaces, woven mats, and exquisite carvings. What remains of their culture today are huge burial mounds and earthworks. Many of the mounds that were opened by archaeologists contained artworks and other goods, which indicate that their society was socially stratified.

Perhaps the largest indigenous center of culture and population in North America was located along the Mississippi River near present-day St. Louis. At its peak in about 1100 C.E., this five-square-mile city, now called Cahokia, was home to more than 10,000 residents; tens of thousands more lived on farms surrounding the urban center. The city also contained 120 earthen mounds or pyramids. Each dominated a particular neighborhood and on each lived a leader who exercised authority over the surrounding area. The largest mound covered 15 acres. Cahokia was the hub of political and trading activities along the Mississippi River. After 1300 C.E., however, this civilization declined, possibly because the area became unable to support the large population.

The majority of American Indians in North America did not live in large population centers. Most lived in small autonomous clans or tribal units. Each group adapted to the specific environment in which it lived. These groups were not unified and warfare among tribes was common as they sought to increase their hunting and fishing areas. Still, these tribes shared some common traits.

A chief or group of tribal elders made decisions. Although the chief was male, usually the women selected and counseled him. Gender roles were not as fixed as they were in Europe, Mesoamerica, and South America. Women typically cultivated corn, beans, and squash and harvested nuts and berries. Men hunted, fished, and provided protection. Both men and women were responsible for raising children and most major American Indian societies in the East were matrilineal (i.e., lineage, family membership, and influence were often through female lines rather than male ones). Women had both power and influence in tribes such as the Iroquois, Lenape, Muscogee, and Cherokee. They counseled the chief and passed on the traditions of the tribe.

This system of sharing power between men and women changed dramatically with the coming of the Europeans. They introduced, sometimes forcibly, their own customs and traditions to the native peoples of North America. Clashing beliefs about land ownership and environmental use were the greatest areas of conflict with the Europeans. Although tribes often claimed the right to certain hunting grounds, American Indians did not practice or, in general, even have the concept of private ownership of land. A person’s possessions included only what he or she had made and used, such as tools or weapons.

Additional Resource

Learn more about ancient American cultures and the flora and fauna of the early Americas by exploring interactive presentations curated by the Library of Congress.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL