Table of Contents |

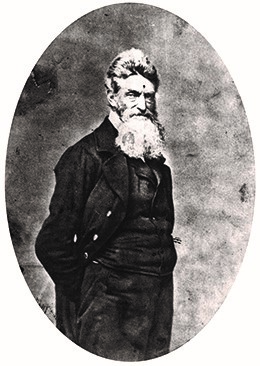

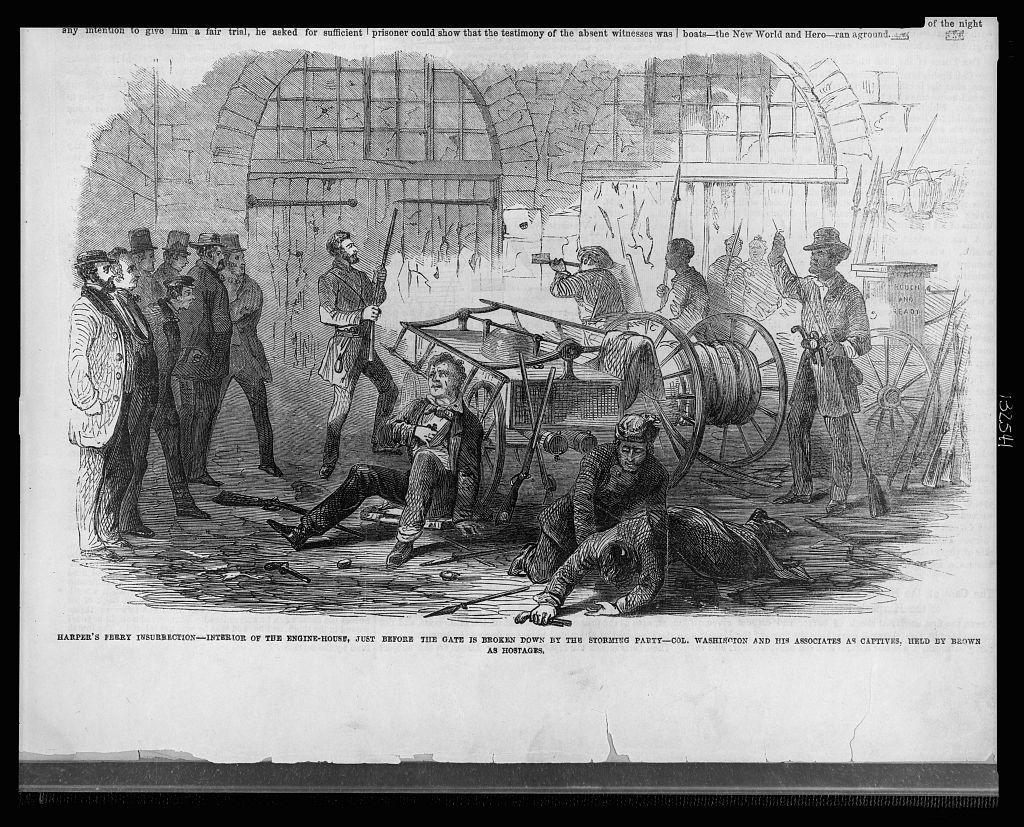

On October 16, 1859, the radical abolitionist John Brown and a small group of armed men attacked the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Brown wanted to capture the weapons in the armory. He planned to distribute them among enslaved people to instigate a revolt that would accomplish one of two outcomes: hasten the onset of civil war between North and South, or encourage a widespread uprising that would end slavery in the South.

Brown wanted to capture the weapons in the armory. He planned to distribute them among enslaved people to instigate a revolt that would accomplish one of two outcomes: hasten the onset of civil war between North and South, or encourage a widespread uprising that would end slavery in the South.

Brown’s force easily took control of the armory, which was lightly guarded. After that, however, the raid fell apart for several reasons:

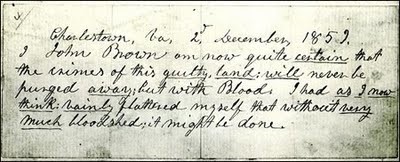

If the raid was not enough to inflame sectional tensions, Brown’s conduct during his trial and execution ignited them further. On the morning before his execution, he wrote a short note defending his actions.

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had as I now think vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.”

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had as I now think vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.”

After his execution, northern public opinion viewed Brown as a martyr. Church bells throughout the North tolled during the hour of Brown’s execution. Leaders of northern African-American communities celebrated Brown by noting that he was one of the few White men who willingly sacrificed his life for the cause of racial equality.

Southerners worried about the possibility of similar plots and were alarmed by northern public opinion. After Brown’s execution, one Maryland resident asked whether it was possible to “live under a government, a majority of whose subjects or citizens regard John Brown as a martyr and Christian hero?”

Although northern political leaders quickly distanced themselves from Brown, southerners were outraged that a majority of northerners condoned his actions.

John Brown’s raid and subsequent execution was the final controversy related to slavery during the 1850s that contributed to the disintegration of the nation. This disintegration continued during the 1860 presidential election, won by Abraham Lincoln, and inspired southern secessionists to withdraw their states from the Union.

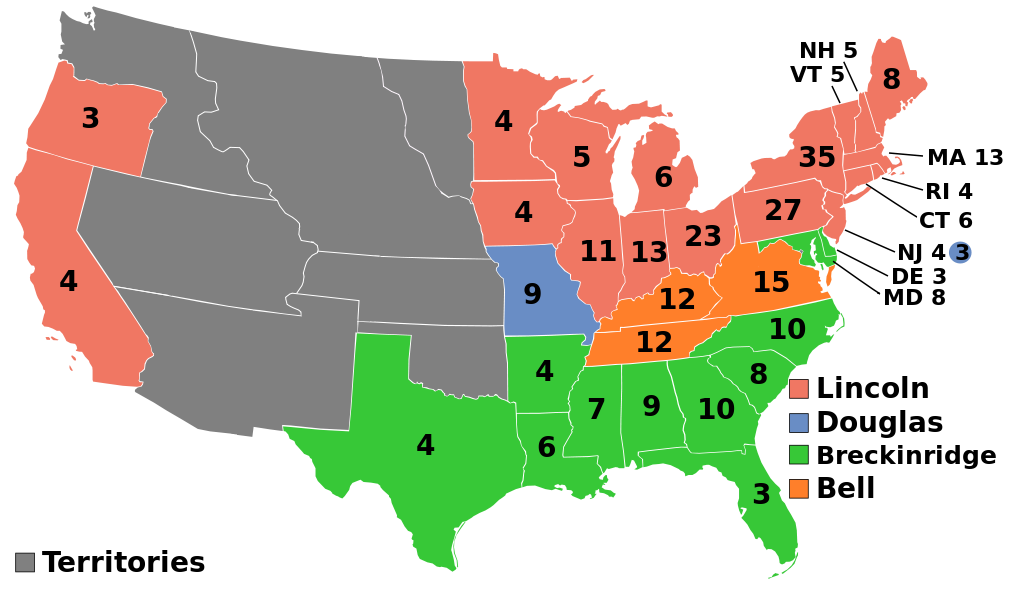

Lincoln’s victory owed much to disarray in the Democratic Party. Before the Party’s nominating convention began, several southern Democratic state organizations vowed to walk out if the party did not support the expansion of slavery into the western territories. When the Democrats nominated Stephen Douglas on a platform that promoted popular sovereignty in the West, southern delegates walked out.

Pro-slavery Democrats held their own convention, nominating John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky (the current Vice President) on a platform that included protection of slavery in western territories. The result was a Democratic Party split along sectional lines: Northern Democrats supported Douglas, and southern Democrats backed Breckinridge.

In the aftermath of John Brown’s raid, leaders of the Republican Party searched for a moderate presidential candidate who could appeal to the minority of northern voters who were abolitionists, as well as the majority who opposed slavery due to their belief in free labor. They nominated Abraham Lincoln for several reasons:

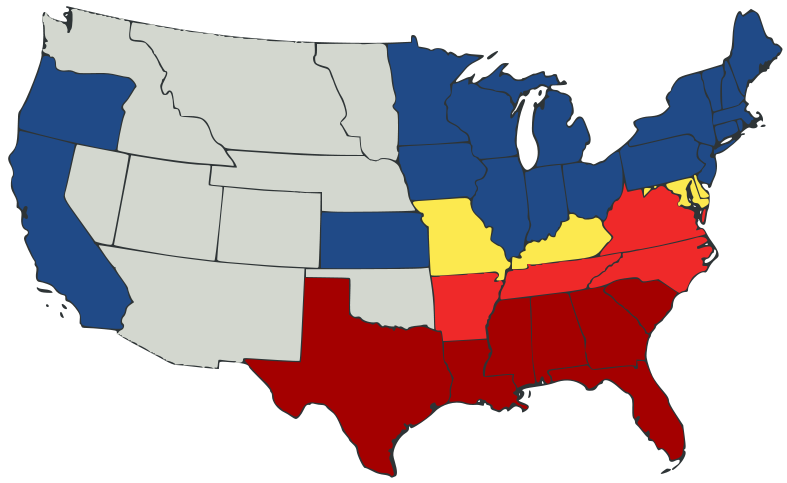

Given the partisan and sectional divisions, two presidential elections essentially took place in 1860: one in the North, between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas; and one in the South, between John Breckinridge and John Bell.

The electoral map reflects these sectional and partisan divides:

Southern states acted quickly in the wake of Lincoln’s election. Rather than accept minority status in a nation in which the majority was hostile to its way of life, and facing a government controlled by a political party (the Republicans) that threatened their economic system, southern leaders moved toward independence.

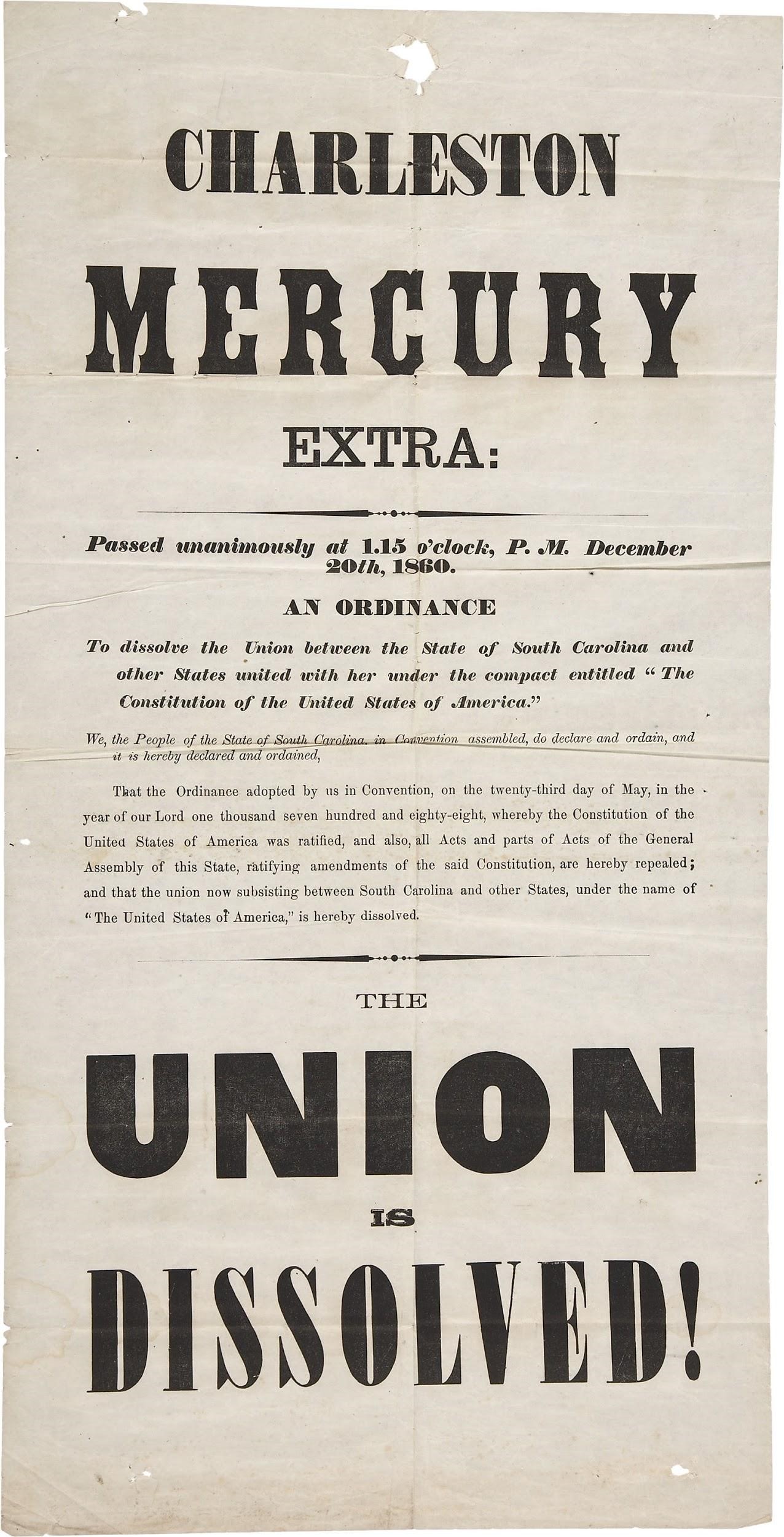

South Carolina, the state with the highest percentage of enslaved people in its population, was the first southern state to secede. It held a convention to examine the issue and, on December 20, 1860, the delegates voted unanimously to leave the Union before Lincoln’s inauguration. By February of 1861, six other states from the Deep South—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—held conventions and seceded from the Union.

The delegates to these conventions justified secession and generated support for their efforts in the following ways:

| Social Contract Theory | Property Rights | White Supremacy |

|---|---|---|

| Delegates insisted that state sovereignty preceded the sovereignty of the federal government that was created by the Constitution. They interpreted the Constitution as a contract: the individual states had agreed to be bound by it, and could break the agreement at any time. | Slaveholders argued that Lincoln’s insistence that slavery could not expand to western territories infringed on their right to acquire and transport property (i.e., purchase enslaved people and move them across state lines or into western territories). | Secessionists argued that the Republican Party sought racial equality, which would destroy the racial hierarchy that slavery had created in the South. Poor White people and wealthy slaveholders agreed that equality was for White men only, enabling them to join together in support of secession. |

The Constitution of the Confederate States of America, or the Confederacy, drafted by the southern states in February of 1861, stated the reasons for secession.

The Confederacy was not a federal union, but a confederation.

The Constitution of the Confederacy strengthened state sovereignty at the expense of national government.

EXAMPLE

State legislatures could impeach Confederate officials who worked within their boundaries. It also forbids the national government to assist in the construction of internal improvements.The Confederate Constitution stated that the government must defend and perpetuate racial slavery. It protected the interstate slave trade, guaranteed that slavery would exist in new territory gained by the Confederacy and, perhaps most importantly, Article One, Section Nine of the Constitution stated that “No.... law impairing or denying the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.”

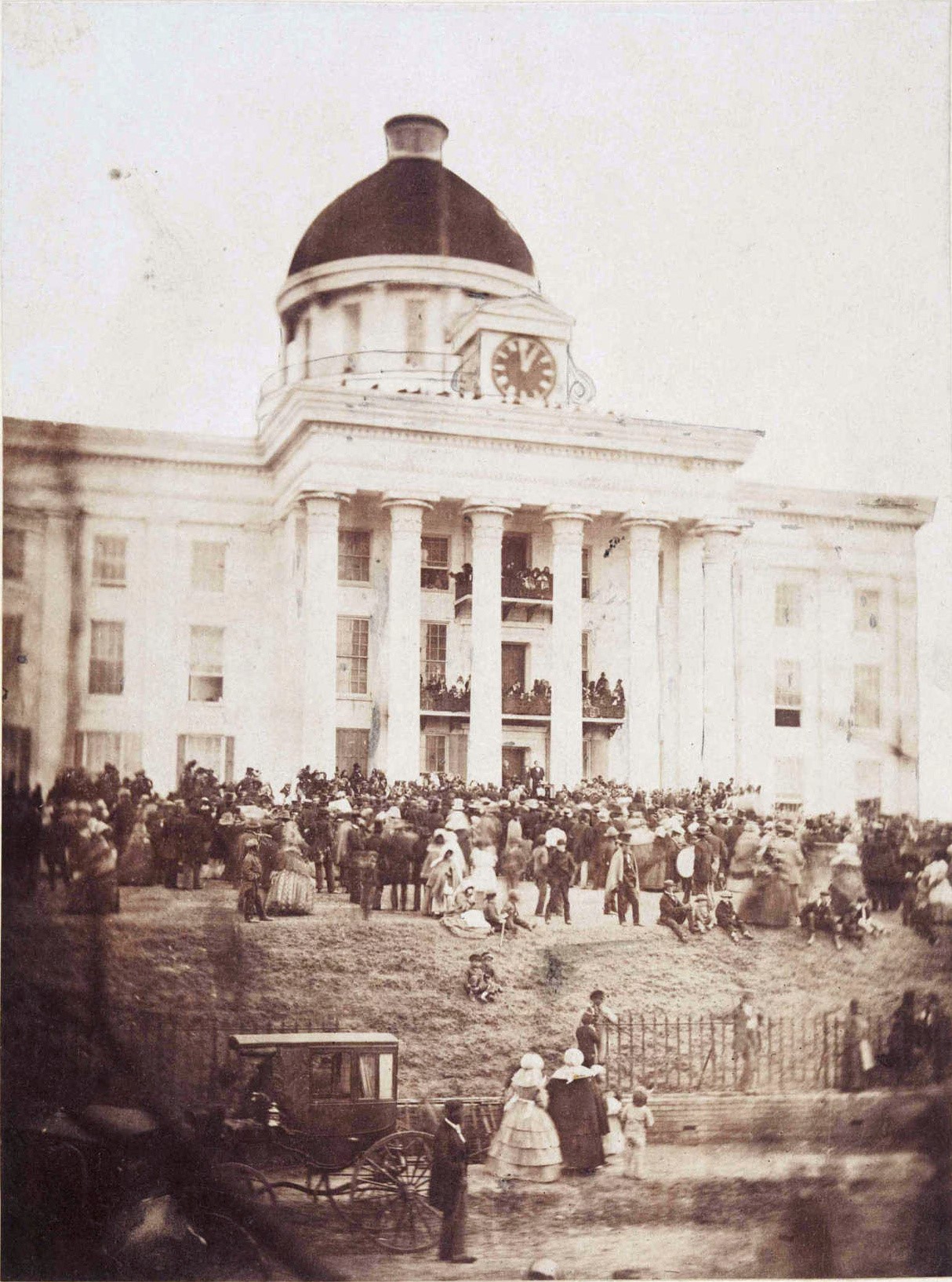

Delegates to the Confederacy’s constitutional convention chose Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and Alexander Stephens of Georgia as President and Vice President of the new country.

By the time of Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861, the Confederacy had already been established. In his inaugural address, Lincoln courted Virginia and the other slaveholding states that remained in the Union, saying, ““I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” In contrast, Jefferson Davis openly encouraged those same states to join the Confederacy.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln rejected secession, arguing that the Union could not be dissolved by the actions of a handful of states. While he did not mention re-taking federal property that the Confederacy had seized, he insisted that the United States would retain control of forts and other federal buildings situated in the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis, meanwhile, encouraged Confederate forces to seize federal property in the South.

Both presidents—Lincoln and Davis—walked a tightrope towards conflict, which erupted at Fort Sumter in April of 1861.

Located in Charleston harbor, Fort Sumter was defended by a federal garrison of fewer than one hundred soldiers and officers. Their situation grew dire when local merchants refused to sell them food and supplies ran low. Lincoln notified South Carolina’s governor that he would resupply the garrison. His strategy was clear: If the Confederates opened fire on resupply ships, the decision to go to war would have been made by the South.

On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces in Charleston began a bombardment of Fort Sumter. Two days later, the Union soldiers surrendered.

News of Fort Sumter’s surrender galvanized both sides. On April 15th, Lincoln proclaimed that a state of insurrection existed in the South and issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to subdue it. The response from northern states was overwhelming. Several northern governors notified Lincoln and the War Department that they would quickly fulfill their quotas and offered additional troops.

Virginia, North Carolina, and Arkansas voted to join the Confederacy. The capital of the Confederate States moved to Richmond, Virginia, only ninety miles south of Washington, D.C. Thousands of young men rallied to the Confederate cause by enlisting in the army.

Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri chose to remain in the Union and became known as “border states”: slaveholding states that maintained allegiance to the Union.

John Brown’s premonition that the nation’s crimes—the injustices and cruelty of slavery—would “never be purged away but with blood” had come true. The attack on Fort Sumter began the Civil War that had been feared for so long.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL