Table of Contents |

The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and absorb those nutrients into the body. Although the small intestine is the workhorse of the system, where the majority of digestion occurs and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, each of the digestive system organs makes a vital contribution to this process.

Consider, for example, the interrelationship between the digestive and cardiovascular systems. Arteries supply the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients, and veins drain the digestive tract. These intestinal veins, constituting the hepatic portal system, are unique; they do not return blood directly to the heart. Rather, this blood is diverted to the liver, where its nutrients are off-loaded for processing before blood completes its circuit back to the heart. At the same time, the digestive system provides nutrients to the heart muscle and vascular tissue to support their functioning.

The interrelationship of the digestive and endocrine systems is also critical. Hormones secreted by several endocrine glands, as well as endocrine cells of the pancreas, the stomach, and the small intestine, contribute to the control of digestion and nutrient metabolism. In turn, the digestive system provides the nutrients to fuel endocrine function.

The table below gives a quick glimpse at how these other systems contribute to the functioning of the digestive system.

| Contribution of Other Body Systems to the Digestive System | |

|---|---|

| Body system | Benefits received by the digestive system |

| Cardiovascular | Blood supplies digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients |

| Endocrine | Endocrine hormones help regulate secretion in digestive glands and accessory organs |

| Integumentary | Skin helps protect digestive organs and synthesizes vitamin D for calcium absorption |

| Lymphatic | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and other lymphatic tissue defend against entry of pathogens; lacteals absorb lipids; and lymphatic vessels transport lipids to bloodstream |

| Muscular | Skeletal muscles support and protect abdominal organs |

| Nervous | Sensory and motor neurons help regulate secretions and muscle contractions in the digestive tract |

| Respiratory | Respiratory organs provide oxygen and remove carbon dioxide |

| Skeletal | Bones help protect and support digestive organs |

| Urinary | Kidneys convert vitamin D into its active form, allowing calcium absorption in the small intestine |

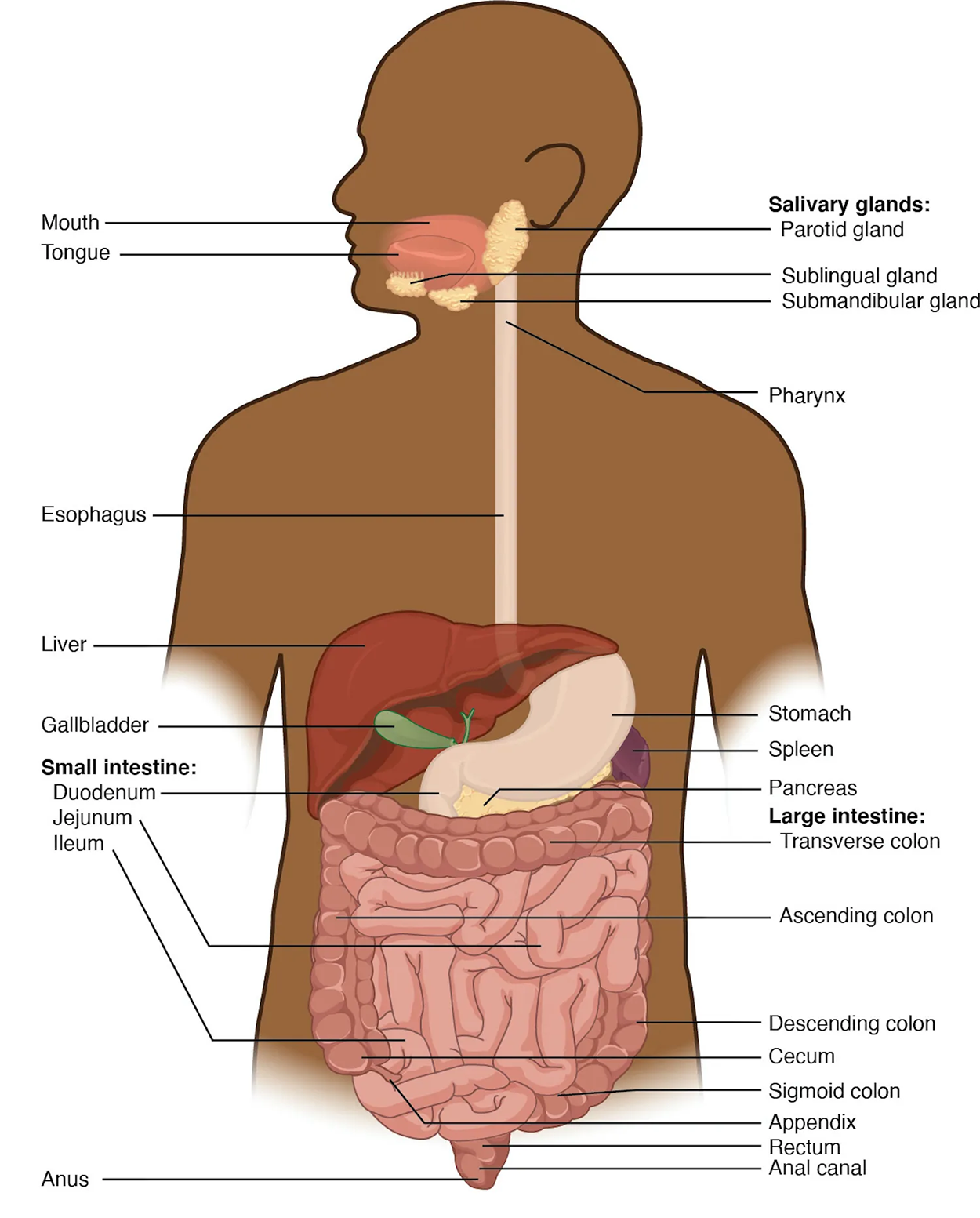

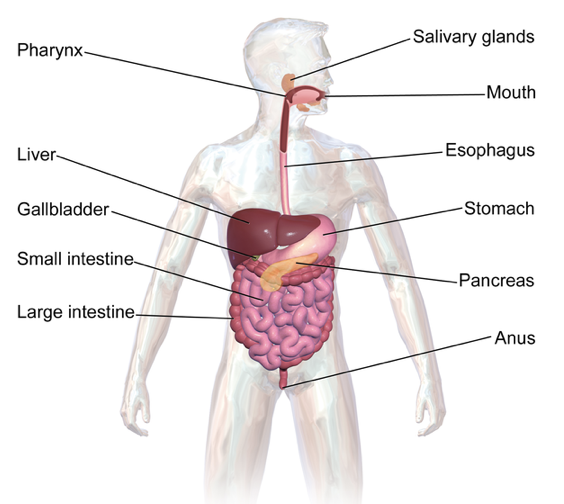

The mouth is the site where food enters our body into the digestive system. Within the mouth, with the help of salivary glands, food is mechanically and chemically broken down; then, you swallow it.

Food then moves towards the pharynx, which is also known as your throat, and then from there moves to the esophagus. The esophagus is the tube that connects your mouth and your pharynx to your stomach (the esophagus lies between the trachea and the spine). Peristalsis is a wavelike motion that will help push food down the esophagus towards your stomach and the rest of your digestive system.

The stomach is a site where food is mechanically and chemically broken down. Mechanical and chemical breakdown occurred in the mouth and then are more extensive in the stomach, where there are different enzymes and gastric juices that chemically digest food.

From there, the food will travel into the small intestine, which is the location where most of the nutrients from the food that you eat are absorbed. The liver, gallbladder, and pancreas help the small intestine break down nutrients using digestive enzymes and juices. After the small intestine, food will then move into the large intestine, where any remaining nutrients and water are absorbed.

Once nutrients, water, and everything that needs to be absorbed have been absorbed, waste will exit out the end of the large intestine (the anus).

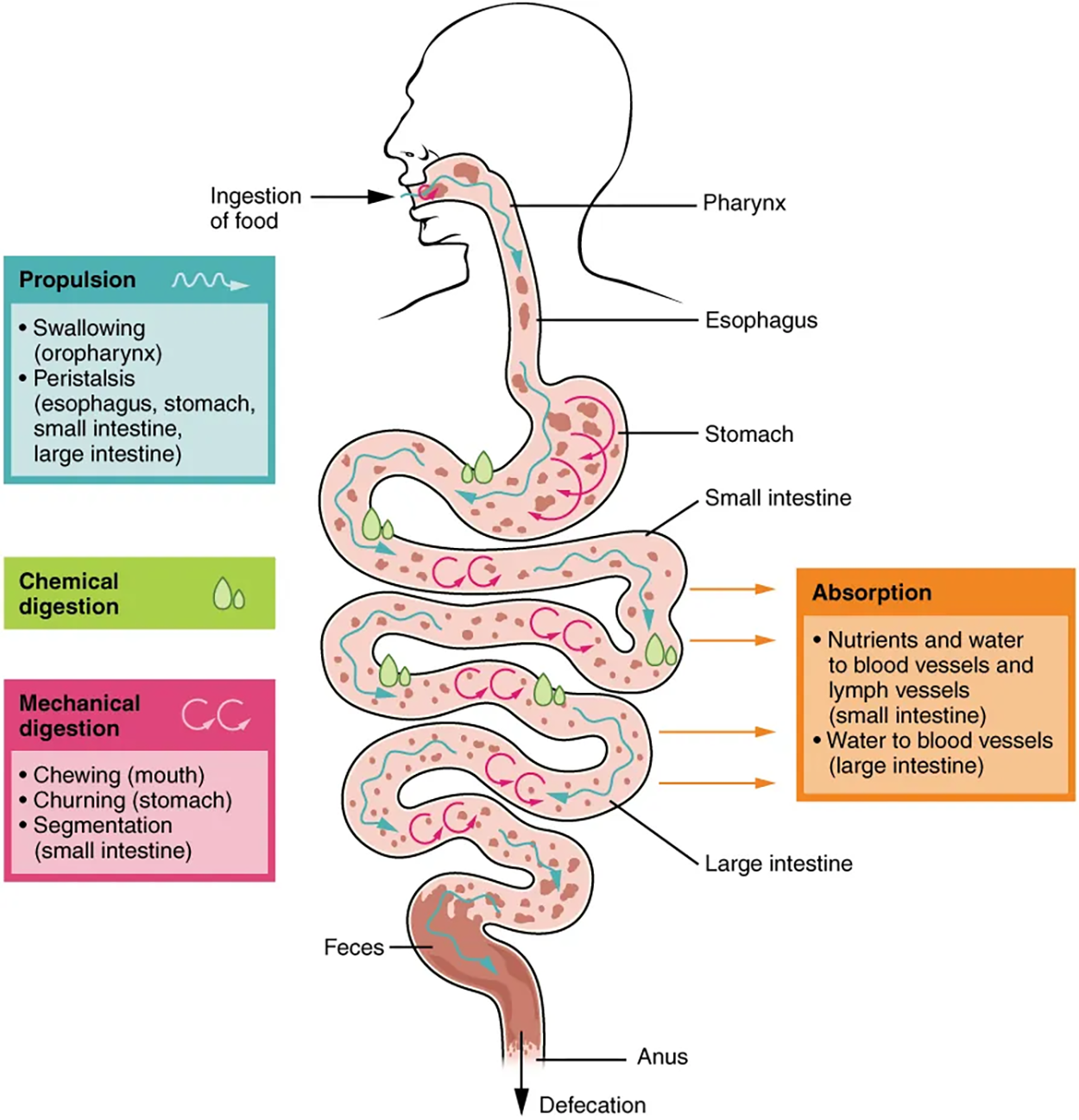

As you learned, the digestive system uses mechanical and chemical activities to break food down into absorbable substances during its journey through the digestive system. There are several processes that facilitate the functions performed by the digestive organs.

The processes of digestion include six activities:

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles propel it into the esophagus.

EXAMPLE

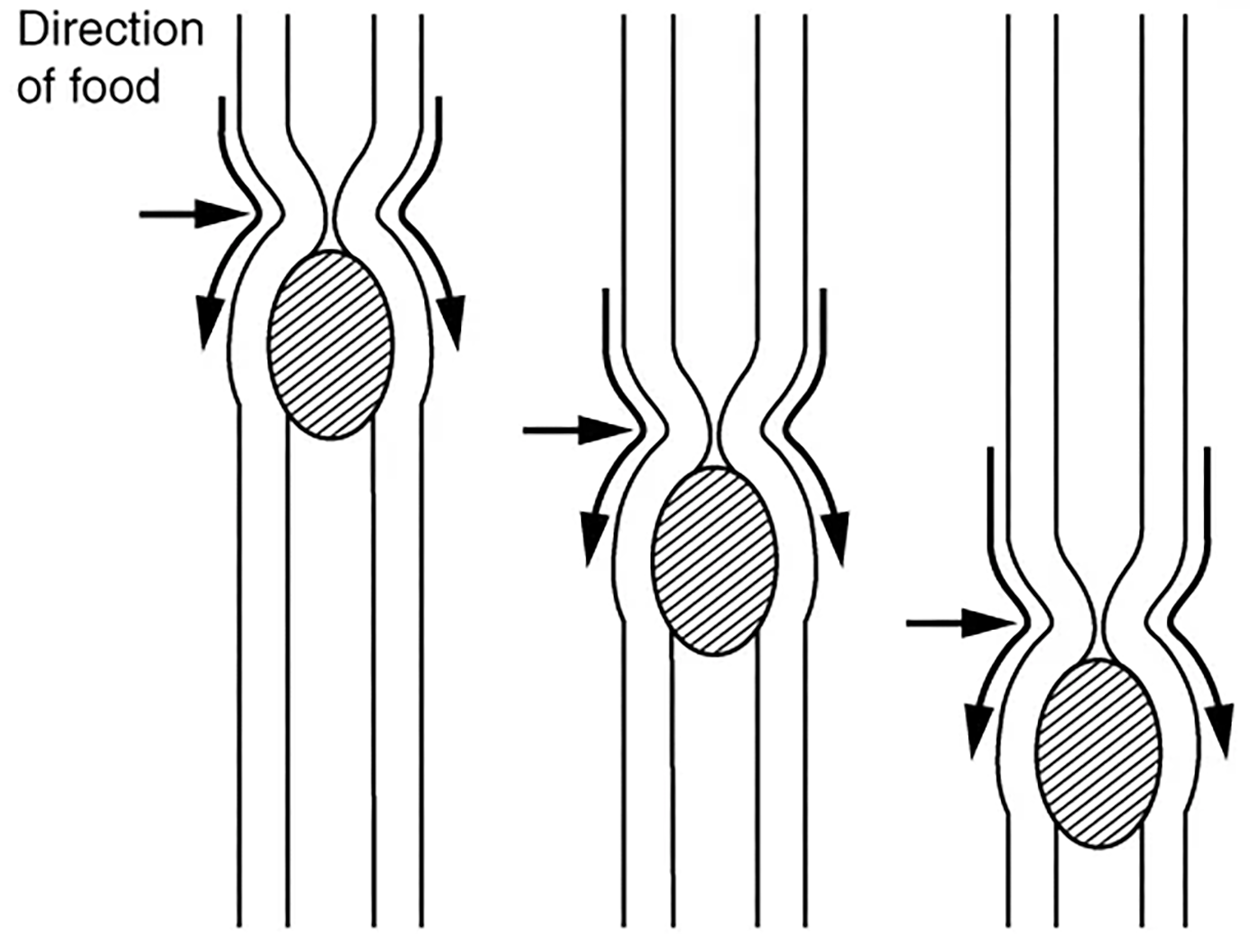

This act of swallowing, the last voluntary act until defecation, is an example of propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis.Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food along. These waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices.

You will learn more about peristalsis in a future lesson.

As you have learned, digestion includes both mechanical and chemical processes. Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility. It includes mastication, or chewing, as well as tongue movements that help break food into smaller bits and mix food with saliva.

Although there may be a tendency to think that mechanical digestion is limited to the first steps of the digestive process, it occurs after the food leaves the mouth as well. The mechanical churning of food in the stomach serves to further break it apart and expose more of its surface area to digestive juices, creating an acidic “soup” called chyme. Segmentation, which occurs mainly in the small intestine (although some does occur in the large intestine), consists of localized contractions of circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal. These contractions isolate small sections of the intestine, moving their contents back and forth while continuously subdividing, breaking up, and mixing the contents. By moving food back and forth in the intestinal lumen, segmentation mixes food with digestive juices and facilitates absorption.

In chemical digestion, starting in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids). These secretions vary in composition but typically contain water, various enzymes, acids, and salts. The process is completed in the small intestine.

Food that has been broken down is of no value to the body unless it enters the bloodstream and its nutrients are put to work. This occurs through the process of absorption, which takes place primarily within the small intestine. There, most nutrients are absorbed from the lumen of the alimentary canal into the bloodstream through the epithelial cells that make up the mucosa. Lipids are absorbed into lacteals and are transported via the lymphatic vessels to the bloodstream (the subclavian veins near the heart). Water, electrolytes, and some vitamins are absorbed in the large intestine. The details of these processes will be discussed later.

In defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces (“stool,” or poop).

IN CONTEXT

Aging and the Digestive System: From Appetite Suppression to Constipation

Age-related changes in the digestive system begin in the mouth and can affect virtually every aspect of the digestive system. Taste buds become less sensitive, so food isn’t as appetizing as it once was. A slice of pizza is a challenge, not a treat, when you have lost teeth, your gums are diseased, and your salivary glands aren’t producing enough saliva. Swallowing can be difficult, and ingested food moves slowly through the alimentary canal because of reduced strength and tone of muscular tissue. Neurosensory feedback is also dampened, slowing the transmission of messages that stimulate the release of enzymes and hormones.

Pathologies that affect the digestive organs—such as hiatal hernia, gastritis, and peptic ulcer disease—can occur at greater frequencies as you age. Problems in the small intestine may include duodenal ulcers, maldigestion, and malabsorption. Problems in the large intestine include hemorrhoids, diverticular disease, and constipation. Conditions that affect the function of accessory organs—and their abilities to deliver pancreatic enzymes and bile (an alkaline solution produced by the liver that is important for lipid digestion) to the small intestine—include jaundice, acute pancreatitis, cirrhosis, and gallstones.

In some cases, a single organ oversees a digestive process.

EXAMPLE

Ingestion occurs only in the mouth and defecation only in the anus. However, most digestive processes involve the interaction of several organs and gradually occur as food moves through the alimentary canal.

Explore in Augmented Reality

Explore in Augmented RealitySOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.