Table of Contents |

Along with the assistance provided by the U.S. Army, Black voter registration and political participation in Reconstruction governments during the late 1860s and early 1870s was encouraged by Union Leagues.

In addition to registering Black voters, Union Leagues disseminated political information and acted as mediators between the Black community and the White establishment. They also helped to build essential community institutions such as schools and churches.

Along with the Union Leagues, other organizations and individuals provided opportunities for Black leadership in politics and communities, including the following:

In addition to politics, African Americans in the South embraced other rights and opportunities previously denied to them. These included the establishment of marriage and family bonds. Following the Civil War, couples no longer under slavery quickly legalized their marriages, often with assistance from the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The first act of freedom for many Black men and women was to locate long-lost spouses and children. A journalist reported having interviewed a freedman who traveled over 600 miles on foot, searching for the family that was taken from him while in bondage.

Former enslaved men and women who had no families often moved to southern towns and cities to be part of a Black community, where churches and mutual aid societies offered help and camaraderie.

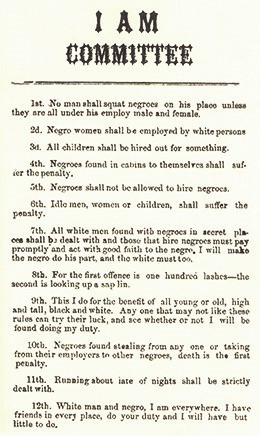

Klan units in the South operated autonomously and with a variety of motives. It was not the only racist vigilante organization: other groups, including the Knights of the White Camelia, the White League, and the Red Shirts, also tended to work autonomously.

The goals of these organizations were identical: to destroy the Union Leagues and other vehicles of Black political organization; reestablish control over African-American labor; and restore White supremacy in the South.

When it came to intimidating White Republicans in the South, the Klan focused on two groups: carpetbaggers and scalawags.

The term “carpetbagger” indicated the disdain of white southerners toward northerners who, sensing a great opportunity, packed up all their worldly possessions in carpetbags (a popular type of luggage) and made their way to the South. The label implied that they were shiftless wanderers motivated only by their desire for quick money, though that was not always the case.

The term “scalawag,” was reserved for White southerners who supported the Republican Party. The label applied to a number of poor White farmers (who did not own slaves), who might have supported the Union during the war or opposed the return of the planters to political power during Reconstruction.

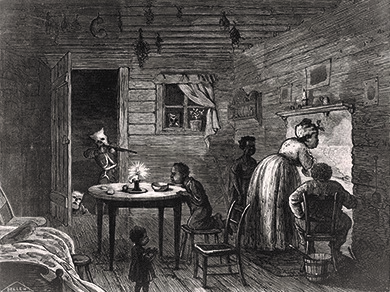

African Americans bore the brunt of violence from the Klan and similar organizations. Klan tactics included riding to victims’ homes, masked and armed, and firing into the houses or burning them down. To prevent the education of Black people, the Klan burned public schools and intimidated teachers. To stop Black people from voting, the Klan threatened, whipped, and murdered Black people and their White supporters.

Klan tactics were designed to create a situation in the South that resembled life during slavery. Klansmen used intimidation and violence to destroy Black economic and political independence, reclaim dominance over Black women’s bodies, challenge Black manhood, and return Black communities to economic, political, and social subservience.

Among the most significant consequences of Klan violence in the South was that it challenged the legitimacy of the state governments established by Congressional Reconstruction.

Unable to end the violence on their own, southern state governments called upon the federal government for assistance against the Klan and other paramilitary organizations. Congress responded in 1870 and 1871 by enacting the Enforcement Acts, which did the following:

Hundreds of accused Klansmen were arrested under the Enforcement Acts, and the Ku Klux Klan ceased to be a viable organization by 1872. Sporadic violence against former slaves persisted into the mid-1870s. However, the southern state governments appeared unable to defend themselves without continued assistance from the army and the federal government.

At the height of Klan violence in 1870, Congress ratified the Fifteenth Amendment.

Although the Fourteenth Amendment addressed citizenship rights and equal protection, it did not prohibit states from withholding the right to vote based on race. The Fifteenth Amendment specifically addressed this by guaranteeing Black men the right to vote.

In order to ensure support for the Fifteenth Amendment, its framers did not include prohibitions of literacy tests and poll taxes. By the end of the 19th century, both were commonly used to disenfranchise African Americans in southern—and northern—states.

Despite this weakness, the Fifteenth Amendment created universal manhood suffrage—the right of all men to vote—and identified Black men, including those who had been enslaved, as having the right to vote. Many White northerners interpreted the Amendment as the culmination of Reconstruction. From their perspective, the federal government had ended slavery, granted African Americans citizenship, and given them the right to vote. They believed that African Americans and southern state governments should now rely on their own resources, and not continue to depend on Congress for support.

As African-American voters and their political leaders at the state level were being intimidated by the Klan, and weariness toward Reconstruction grew among northern voters, the South experienced a resurgent Democratic Party.

Leaders of this resurgence, who called themselves redeemers, were committed to rolling back Congressional Reconstruction, discrediting the Republican Party in the South, and reestablishing southern state governments under the Democratic Party.

By the mid-1870s, the redeemers made significant gains in wresting control from Republican-dominated state governments. They did so despite the Enforcement Acts, and federal efforts to curb political violence.

EXAMPLE

In 1873, following a contested gubernatorial election in Louisiana, armed members of the Democratic Party attacked the town of Colfax, killing as many as 150 former enslaved people loyal to the Republican Party. The Colfax Massacre was the deadliest episode to occur during Reconstruction.By 1876, a presidential election year, the Democrats had regained control of a majority of southern states. Only a few Republican-led states — South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida—remained.

In South Carolina, Democrats nominated a former Confederate general, Wade Hampton, for governor in 1876. Party members formed rifle clubs, known as Hampton’s “Red Shirts”, to intimidate Republican voters.

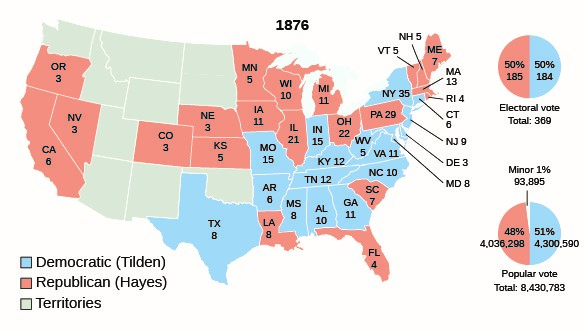

The presidential election pitted Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, a three-time Governor of Ohio, against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, Governor of New York. The election was very close and appeared to result in a Democratic victory. Tilden had carried the South and large northern states such as New York. He had a 300,000-vote advantage in the popular vote. However, the Republicans contested the returns from South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana.

To avoid another Civil War, Congress attempted to break the deadlock by appointing a special electoral commission in January 1877. The commission consisted of 15 individuals: ten Congressmen, divided equally between the parties, and five Supreme Court Justices. One of the Justices, David Davis, resigned when the Illinois legislature elected him to the Senate. President Ulysses S. Grant selected a Republican to take Davis’s place on the commission, which tipped the scales in Hayes’s favor. Voting along party lines (8 to 7), the commission awarded the contested electoral votes and, therefore, the presidency, to Hayes.

The Democrats threatened to challenge the commission’s decision in court. To avoid this, party leadership on both sides worked out the Compromise of 1877. In exchange for Hayes' victory, Democrats received the following:

The Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction as a distinct period of American history. Contrary to popular belief, President Hayes did not order the withdrawal of all federal troops from the South. Rather, he ordered the federal troops guarding the South Carolina State House to return to their barracks.

This was significant because it accepted what had been accomplished by Democratic redeemers, who gained political control of the South a little over a decade after the Civil War. Hayes’s order also signified that the federal government would no longer play a role in the South’s political affairs, including protection of the rights of African Americans, and of all citizens.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL