Table of Contents |

The landslide victory of Herbert Hoover (image on the right) over Democrat Al Smith in the presidential election of 1928 was the culmination of the “Republican ascendency” of the 1920s. The decade witnessed the return of a pro-business federal government, led by Republican Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and, beginning in March 1929, Herbert Hoover. Republicans also dominated both houses of Congress during the 1920s.

The landslide victory of Herbert Hoover (image on the right) over Democrat Al Smith in the presidential election of 1928 was the culmination of the “Republican ascendency” of the 1920s. The decade witnessed the return of a pro-business federal government, led by Republican Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and, beginning in March 1929, Herbert Hoover. Republicans also dominated both houses of Congress during the 1920s.

President Herbert Hoover set an agenda that he believed would continue the prosperity of the 1920s. In his view, the government should partner with the American people, but individual citizens should rise (or fall) according to their abilities. With this in mind, he planned an immediate overhaul of federal regulations so that excessive government control would not hinder the growth of the nation’s economy.

Hoover was also known as a humanitarian and a reformer, based on his accomplishments as a public servant before he became president.

EXAMPLE

When World War I began in Europe, Hoover led food relief efforts that prevented the starvation of millions of Belgians during the German occupation. When the United States entered the war, President Wilson appointed Hoover as head of the U.S. Food Administration, which coordinated rationing efforts in America and secured essential food items for Allied forces and civilians in Europe.Hoover’s first months in the White House provided additional evidence of his reformist, humanitarian spirit:

Much of the optimism that surrounded Hoover’s administration was based on confidence in the economy among middle-class and wealthy Americans. As the Great Crash unfolded, it became evident that their confidence was misplaced and that underlying weaknesses in the economy had been overlooked.

Rising incomes during the 1920s had much to do with the widespread optimism regarding the economy. In 1922, almost 600,000 Americans had annual incomes that exceeded $5,000. By 1929, over 1 million had an annual income that exceeded that amount.

Increasing incomes enabled many Americans to purchase homes, automobiles, and electric appliances. Many of them also invested their money. Traditional options, including savings accounts and life insurance, continued to be available to them, but some chose to speculate on riskier investments, hoping for larger returns.

The federal government, most notably Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and the Federal Reserve, encouraged the increase in speculation during the 1920s. Following a brief postwar recession (1920–1921), the Fed lowered interest rates and eased the reserve requirements on the nation’s largest banks. As a result, the money supply in the United States increased by almost 60% during the decade. This convinced many middle- and upper-class Americans that investing—including speculation—was safe.

The abundant supply of money, along with low interest rates (which made borrowing easier), led to the rise of several questionable investment schemes during the 1920s.

EXAMPLE

“Ponzi schemes,” named for vegetable-seller-turned-Wall-Street-trader Charles Ponzi, encouraged novice investors to back unfounded ventures. Speculators used the funds provided by those investors to pay off older investments, which enabled the venture to grow, enticing more people to invest in it.Commercial banks, as well as deposit institutions that originally avoided investment loans, began to offer easy credit, which enabled people to invest—even if they lacked the money to do so.

Before the stock market crash of 1929, there was evidence that ongoing speculation was not sustainable. One example was the Florida land boom of the 1920s.

Beginning in the early 1920s, real estate developers promoted South Florida as a tropical paradise. They convinced a number of investors to go “all in,” buying land they had never seen with money they did not have. Many of them then sold the land to other investors at higher prices.

The land boom went bust in 1926. Negative press reports regarding the speculative nature of the boom, along with federal investigations into the practices of several land brokers and a railroad embargo that limited the delivery of construction supplies to South Florida, reduced investor interest. A hurricane in 1926 drove many of the developers to bankruptcy.

Like the advertisers of domestic appliances who targeted women (and reinforced gender stereotypes), advertisers of real estate in Florida (and elsewhere in the United States) preyed upon the hopes and aspirations of potential investors.

Despite the publicity surrounding the boom and bust of Florida real estate, speculation continued, especially in the stock market.

By the late 1920s, some investors were buying stock “on margin”—for a small down payment, made with borrowed money, and with the intention of selling it quickly for a much higher price before the remaining payment was due. This strategy could work, as long as stock prices continued to increase. Furthermore, the opportunity to buy stock for a small down payment encouraged many Americans (who might not have done so otherwise) to invest in the stock market.

These tactics were developed in the absence of federal regulation of the stock market. They were used by retail stock brokerage firms, which catered to average investors who wanted to get into the market but lacked ties to investment banking houses or large brokerage firms.

EXAMPLE

As many as 1,600 brokerage firms were in business in the United States by 1929. Most Americans did not have to go to Wall Street or follow the stock market to invest.In September 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average peaked at 381 points, roughly 10 times the market’s value at the beginning of the 1920s.

Amid these waves of speculation, several warning signs indicated that a crash was coming.

EXAMPLE

A brief downturn in the market on September 18, 1929, raised questions among investment bankers and led some of them to predict an end to high stock values.EXAMPLE

A steep sell-off of automobile stocks on October 23, 1929, decreased stock values and threatened the accounts of thousands of investors who had purchased stock “on margin.” Overnight, brokerage firms issued “margin calls” to their clients, which required investors to increase their down payment on their stocks or sell their stocks if they could not do so.Nothing could have prepared traders for October 24, often referred to as “Black Thursday.” On that day, the New York Stock Exchange lost 11% of its value as thousands of investors, unable to meet their margin calls, attempted to sell their shares but found few buyers. To prevent a panic, leading investment banks, including Chase National, National City, and J. P. Morgan, purchased large amounts of stock to prevent prices from collapsing.

Market fluctuations continued into the next week. The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost another 13% of its value on Monday, October 28. The situation worsened the next day, October 29, also known as Black Tuesday.

No one heard the New York Stock Exchange’s opening bell on October 29; shouts of “Sell! Sell!” drowned it out. In the first 3 min after it rang, nearly 3 million shares of stock, worth $2 million, changed hands. Banks, facing debt and seeking to protect their assets, demanded payment for the loans they had made to individual investors. Stock belonging to investors who could not pay was sold immediately. In some instances, their life savings were wiped out in minutes.

Stockholders traded over 16 million shares—and lost over $14 billion—on Black Tuesday. To put this in context, a day when 3 million shares were traded was considered a busy day on the stock market.

The financial outcome of the Great Crash was devastating. Between September 1 and November 30, 1929, the stock market lost over half its value, dropping from $64 billion to approximately $30 billion. What distinguished this crash from previous panics was its impact on millions of Americans, not just a small number of stock market investors.

EXAMPLE

While only 10% of American households owned investments, over 90% of all U.S. banks invested in the stock market.The Great Crash was not the sole cause of the Great Depression, nor did the crash occur in a vacuum. Rather, the crash exposed underlying weaknesses in the economy, specifically in the nation’s banking system.

An uneven distribution of wealth among Americans compounded the structural flaws in U.S. banks.

EXAMPLE

In the 1920s, 80% of American families had almost no savings, and approximately 1% of Americans controlled over a third of the nation’s wealth.This meant that few new investors were entering the market by 1929; there was no one to purchase stock from sellers when the speculative boom crashed in October. Americans who had savings often lost everything in their accounts, since banks had invested their money in the stock market.

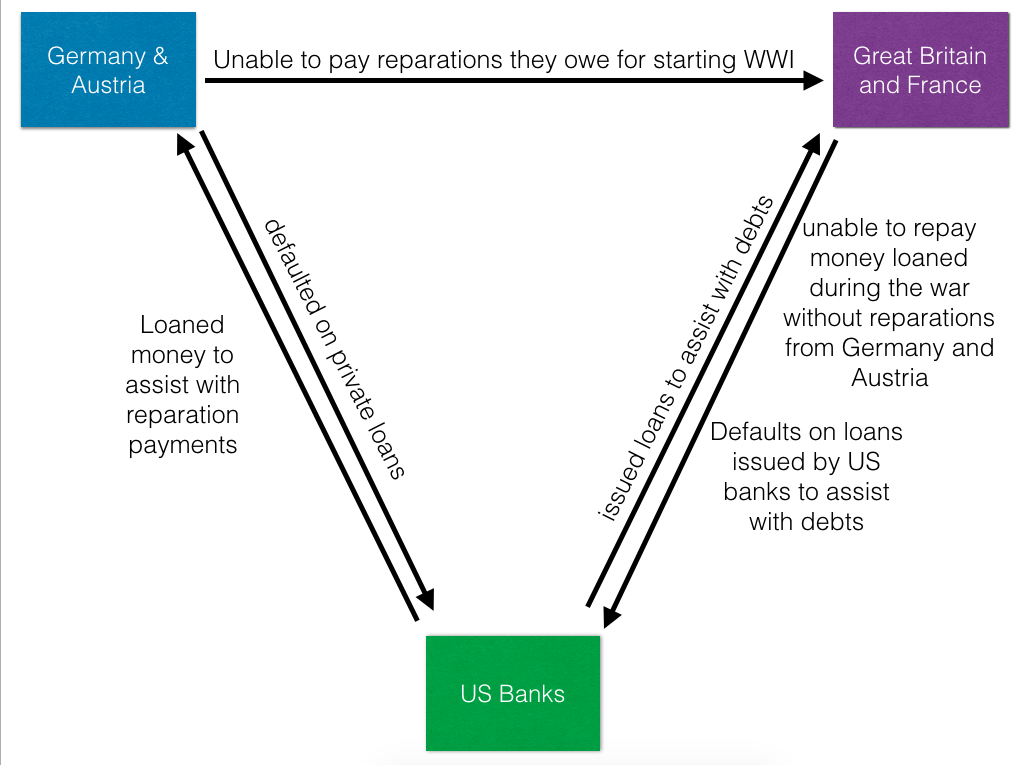

There was also an important international contribution to the Depression, one linked to the Treaty of Versailles and the reparations that Germany and Austria owed to Great Britain and France for starting World War I:

Given the financial situation in the United States and Europe, large numbers of investors and the general public withdrew their money from banks. They feared that the banks would fail. As more people withdrew their money in bank runs, the banks were driven to insolvency.

The bank runs indicate that a loss of confidence in the U.S. economy and financial institutions was an important cause of the depression. For much of the 1920s, Americans believed that prosperity would continue and that markets would keep growing. Following the Great Crash, the market was stagnant and the foundations of the banking system were shaky. Americans wondered whether the country’s economic structures would be able to weather continued market volatility.

Panic and pessimism were prevalent in the aftermath of the Great Crash. Banks closed their doors or restricted operations, leaving many customers penniless. There was little investment in industries such as automobiles and construction.

EXAMPLE

In November 1929, fewer cars were built in the United States than in any other month since November 1919.The downturn experienced by major industries led to and reflected the limited purchasing of consumers and businesses. As the U.S. economy descended into depression, Americans lost the drive for the conspicuous consumption that they had exhibited during the 1920s. Businesses, with no market for their products, had little incentive to hire workers or purchase raw materials.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL