Table of Contents |

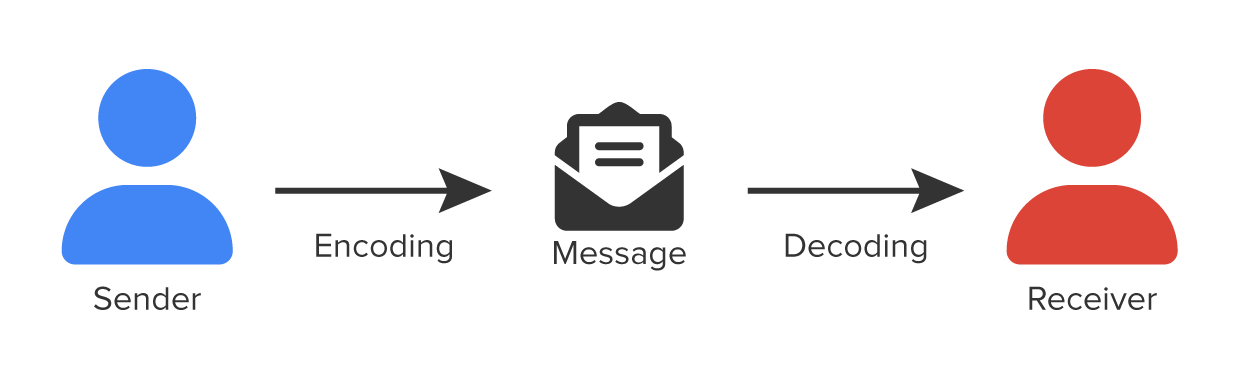

Communication suggests a linear process. There’s a sender, who has information to pass on to someone else. There’s a message, the information the sender wants to pass on, and the receiver, the person who needs to get the message.

The sender puts their thoughts into words (or gestures, or graphics, or numbers). This process is called encoding. The receiver hears (or reads, or sees) the message and attempts to make sense of it. This is decoding. This is a common communication model used by people in different disciplines to describe the communications process. The model appears below, but is not yet complete.

People don’t often think about the encoding and decoding process unless there are challenges, such as if they aren’t sure how to put your message into words, or the recipient doesn’t understand the words used by the sender. But in truth these elements are always present. Like many things, people take them for granted until something isn’t working!

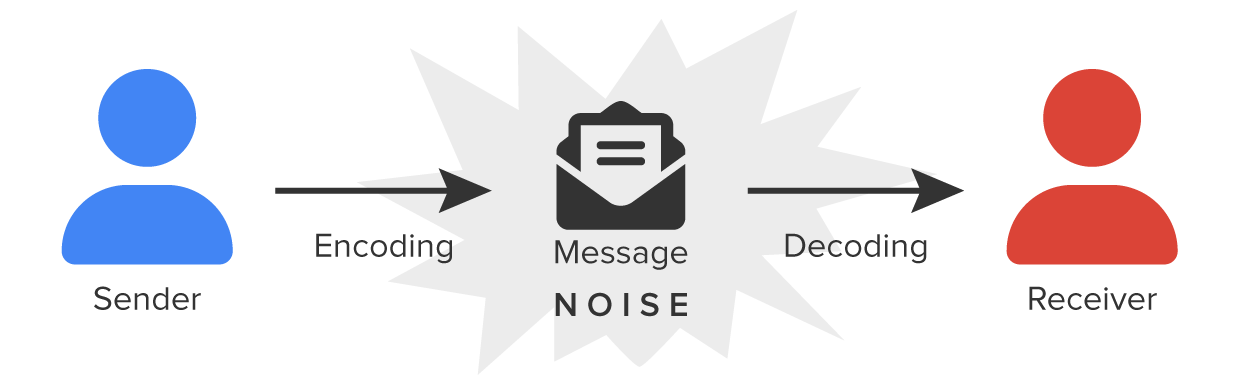

Problems occur due to noise. Noise is anything that interferes with the message: distractions, language barriers, or lack of focus. It can be a concept misunderstood by the sender before the message is even formed, it can be a message that’s not articulated properly, or it can be a message that’s just not understood by the receiver. It can also be external to the communication taking place such as people talking in the background or something that distracts you while you’re talking. Let’s revise the model to include the presence of noise. Noise is always present to some degree, but it usually isn’t enough to interfere with the message.

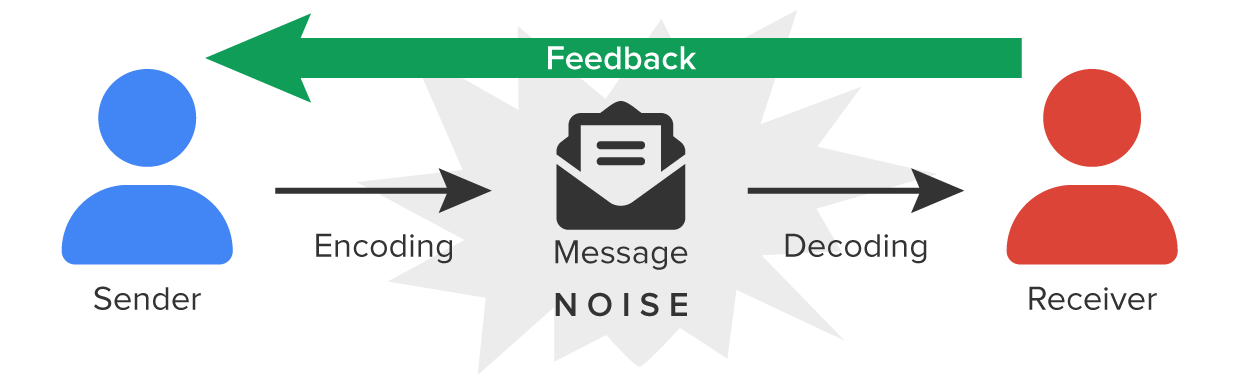

After the recipient receives the message, they will nod, say something like “gotcha,” or perhaps look puzzled and ask for clarification. This is feedback. Some feedback is nonverbal, even involuntary. If the recipient looks confused but doesn’t say a word, you still have useful feedback that your message isn’t successful. Either way, just like noise, there is always feedback. Even a moment of absolute silence is feedback! Let’s revise the model one more time to include this element.

The communication model may seem like common sense (indeed, it is all ingrained into our communication process as children), but being mindful of the model can make you a more effective communicator. Remember to check for nonverbal cues (feedback) that signal if the message isn’t understood, even if the person says they get it. (Maybe they are embarrassed to admit they need more help). And if the feedback is that the message is not correctly received, you can examine each element of the process—encoding, decoding, and noise—before you fault the recipient for not paying attention.

EXAMPLE

Bill has asked his new intern, Dana, to get something for him from his colleague Emily's office. Dana responds "Okay…", and hesitates before leaving his desk. He takes this feedback and considers what the noise might be that is getting in the way of a simple request. He realizes that Dana probably doesn't yet know the names of everyone in the office. Bill changes his communication, clarifying that Emily's office is on the third floor and that she has red hair, so that Dana can more easily find her.The model is also important to your role as a recipient. Are you minimizing noise so you can process the message correctly? This can mean pausing other activities when you take a call or read an important email, or asking colleagues to quiet down so you can hear! But sending feedback is also important. You may think you understand a message from your boss perfectly and go about completing the task, but giving substantial feedback about what you take the task to be will either give the boss a chance to clarify or simply reassure them that you’re on the right track.

Say your colleague is going to be working remotely later and you want her to stay in touch with the team. Several staff members use the Discord communications app for team work.

“Do you have Discord so you can stay in touch?” you ask her. “If not, you need to get it.”

“What cord?” she asks.

You in turn are confused by the question. You think your colleague is talking about something else entirely.

But you remember the communication model. Your worker has given you feedback, and from that you can tell the message was not received correctly. You think about coding and decoding and quickly realize that the coworker heard something different than what you said.

“Discord, with a D,” you tell her. You remember a generational difference, that the older colleague may not be as used to such communication tools as you and your peers, and this has created noise. So you explain further. “It’s a communications app that helps teams chat on the fly when they’re physically apart.”

“Ah, it’s like Slack!” she says, now decoding the message in a way that makes sense to her. “Sure, I’ll download the app and let you know when I’m all set up.” By being mindful of coding, decoding, noise, and feedback you quickly cleared up a misunderstanding that might have otherwise devolved into an Abbott & Costello routine!

Of course, not all miscommunication is resolved this simply, but remember that any message will include these elements. Whether you are talking on the phone or sending an email you can do things like check for noise and ask for feedback. You can think carefully about your encoding and—because you are aware of your audience—be sure to do it in a way that decoding is likely to be successful.

Source: This tutorial has been adapted from Lumen Learning's "Business Communication Skills for Managers." Access for free at https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-businesscommunicationmgrs. License Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.