Table of Contents |

To protect its interests in the Pacific against Japanese expansion, the United States applied a series of economic sanctions against Japan and sent military supplies to the Chinese.

Beginning in July 1940, the United States enacted an embargo (i.e., a ban on trade) on the shipment of certain materials to Japan, including gasoline, machine tools, and scrap iron and steel. By late 1941, Japan felt the pressure resulting from the embargo.

Japan was determined to obtain a sufficient supply of oil and planned to seize the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) to satisfy this desire. A key American possession—the Philippines—was located between Japan and Indonesia. Japan first attempted to end the embargo diplomatically, but the negotiations broke down in November 1941. This convinced the Japanese that they would have to go to war against the United States.

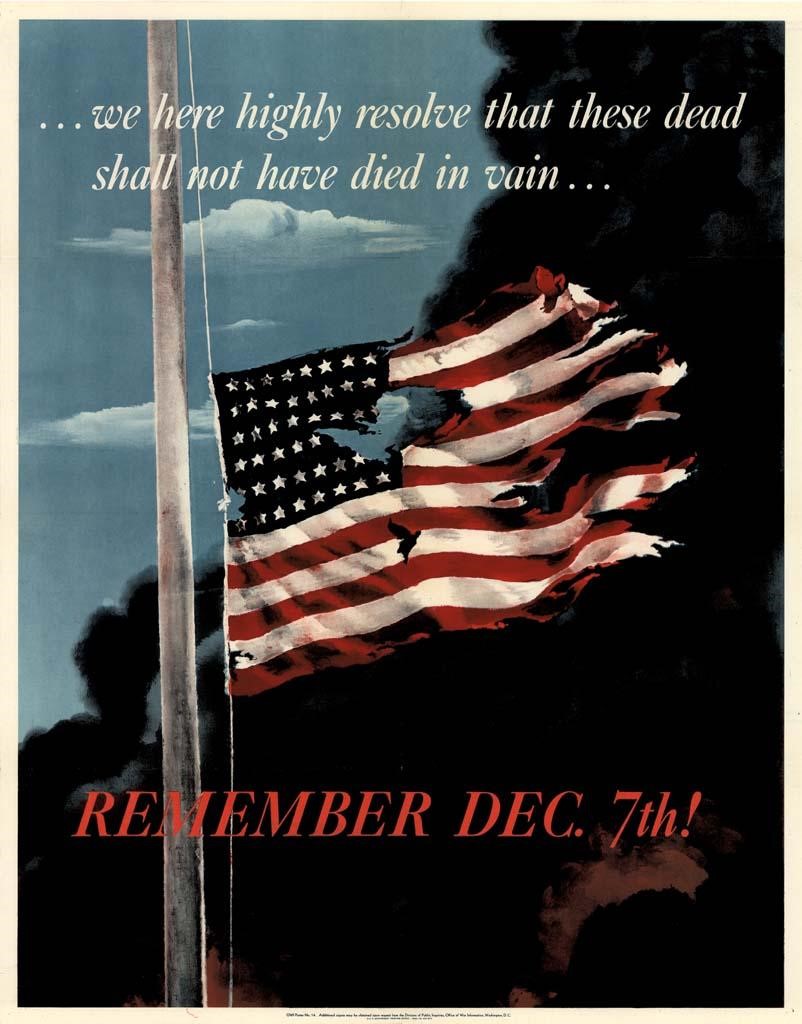

In early December of 1941, two Japanese fleets were mobilized in the Pacific. One moved toward Hawaii under cloud cover and radio silence. On the morning of December 7, it launched a surprise attack on the American fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor.

Some 353 Japanese fighter planes, bombers, and torpedo bombers attacked the American ships, hitting all of the eight battleships anchored in the harbor. Four of them sank. Nearly 200 American planes were destroyed on the ground, and 2,400 servicemen were killed. Another 1,100 were wounded.

The second Japanese fleet moved southeast, attacking Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies in late 1941 and early 1942. It also attacked the American island possessions of Guam, Wake, and the Philippines.

Rather than provide a knockout blow to the United States, the attack on Pearl Harbor invigorated American support for involvement in World War II. It convinced citizens to support the war effort in any way that they could, including in the workplace. Unfortunately, the attack also revived racial discrimination toward Japanese Americans.

President Roosevelt, referring to December 7 (when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor) as “a date which will live in infamy,” asked Congress for a declaration of war. The declaration was delivered to Japan on December 8. On December 11, Germany and Italy, in observance of their alliance with Japan, declared war on the United States.

Additional Resource

Listen to the audio of FDR’s speech “December 8, 1941: Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War” (following the attack on Pearl Harbor) from the Miller Center.

U.S. entry into World War II changed everyday life for all Americans. One positive result was that the demands of wartime production finally ended the economic depression that had plagued the country since 1929.

The United States had been preparing for war before the Pearl Harbor attack. The government had stimulated investment and development of factories and infrastructure in the West in anticipation of a war in the Pacific.

The populations of cities in California, Oregon, and Washington grew as thousands of Americans traveled to the West Coast to take up jobs in defense plants and shipyards.

EXAMPLE

The population of Richmond, California, jumped from 20,000 to 100,000 within 3 years of Congress’s declaration of war.Additional Resource

Watch a short newsreel about industrial production in WWII from PBS.

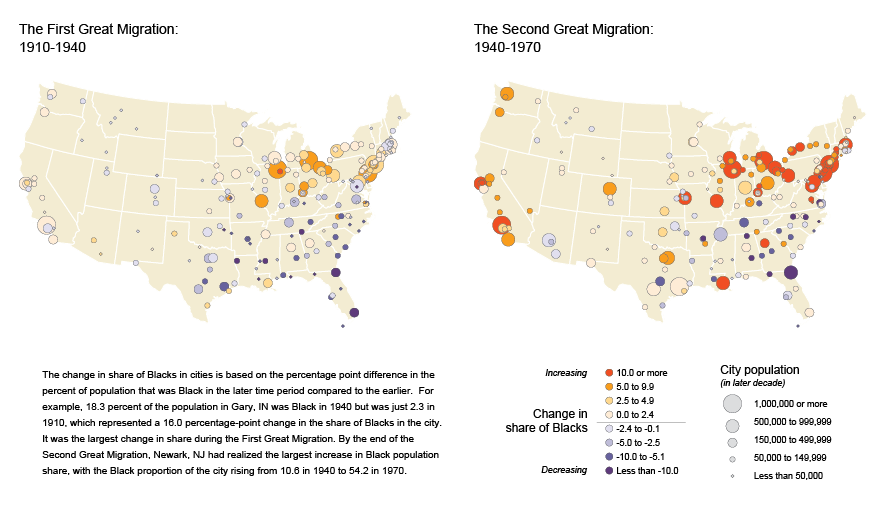

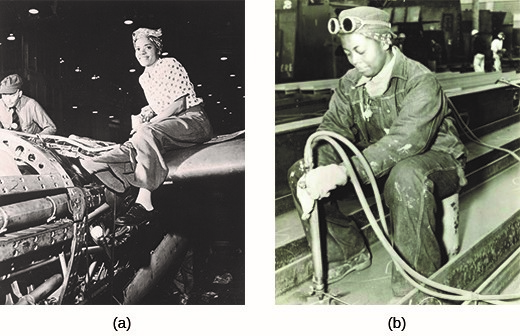

Mobilization of the economy for wartime production created opportunities for women. They often relocated on their own, or with their husbands, to military bases and cities to work at jobs in the defense industries. Like the Great Migration that followed World War I, many African Americans migrated from the South to Northern and Western cities in search of new places to live and work.

Wartime conditions enabled some women to work at high-paying defense plant jobs. Others were employed in factories and offices. This enabled them to earn more money than they ever had, but their wages remained lower than those earned by men for the same work. Despite this inequality, many women achieved a degree of independence and financial self-reliance by working during the war.

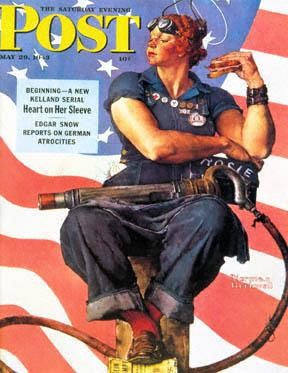

To recruit women for wartime jobs—and to counter criticism that women did not belong in such occupations—the federal government conducted an advertising campaign centered on a character known as Rosie the Riveter.

Rosie, who was a composite based on several women, was depicted by illustrators such as Norman Rockwell and J. Howard Miller.

Rosie looked strong and tough but also feminine. By picturing Rosie wearing lipstick and makeup, illustrators and factory owners sought to reassure men that wartime employment would not result in “masculine” women. Some factories went so far as to give female employees lessons on how to apply makeup. The federal government did not ration cosmetics during the war.

Employers and federal officials promoted female workers’ feminine attributes because the increased employment of women required recognition of their dual roles as employees and mothers.

EXAMPLE

In 1944, 33% of women working in defense industries were mothers who worked “double-day” shifts: one shift at the plant and another at home.To address the dual roles of women, Eleanor Roosevelt urged her husband to approve the funding of childcare facilities by the federal government under the Community Facilities Act of 1942. She also urged employers to build childcare facilities for their workers. By the end of the war, the government had funded childcare centers that served hundreds of thousands of children.

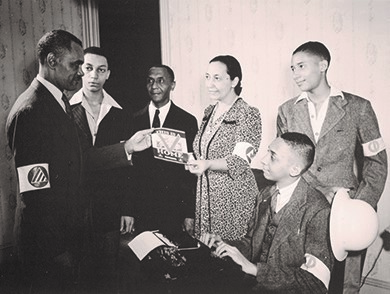

The need for Americans to come together to support the war effort after the Pearl Harbor attack led to a spirit of unity throughout the population. However, African Americans continued to be treated as second-class citizens, despite their proclamations of patriotism, participation in the workplace, and willingness to fight overseas.

By 1941, Black communities had forged promising relationships with the Roosevelt administration through the work of Mary McLeod Bethune and African Americans who were federal employees. However, the Southern states—and the armed forces—remained legally segregated. Private corporations also discriminated in their hiring and compensation policies.

To protest the near-complete exclusion of African Americans from jobs in wartime industries, A. Philip Randolph of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) called for a “March on Washington.” On June 25, 1942, days before the march was scheduled to occur, Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802.

To enforce the order, Roosevelt established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to investigate complaints of discriminatory practices. The FEPC required the defense industries to hire Black workers.

However, the FEPC was often unable to force corporations to place African Americans in well-paid and managerial positions.

EXAMPLE

At a plutonium production plant in Hanford, Washington (overseen by the DuPont Corporation), African Americans were hired as low-paid construction workers but not as laboratory technicians.Still, the existence of the FEPC indicated a shift in federal policy regarding Black equality and reflected the emergence of a civil rights movement in the United States.

At this time, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded by James Farmer, engaged in sit-ins and other forms of peaceful protest to desegregate public facilities in Washington, DC. CORE’s goal was to deprive the Axis Powers of the ability to label the United States a racist country. They argued that since the United States had denounced Germany and Japan for violating human rights, our country should be a positive example in that area.

The efforts of Black civil rights activists to advance equality during World War II were in accordance with the Double V campaign outlined in the Pittsburgh Courier, the largest Black newspaper in the country.

The campaign attempted to broaden the wartime goals of the United States by encouraging African Americans to win two “Vs”: victory over racism at home and victory over America’s enemies abroad. These goals became the key tenets of the modern civil rights movement after World War II ended.

The desire for American unity in support of the war following Pearl Harbor led President Roosevelt and military leaders to discriminate against Japanese Americans through forced relocation and internment policies.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reinvigorated racist assumptions about Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans in the United States. As a result of revived racism and widespread fear of espionage and sabotage in the West, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. It gave the army the authority to remove people from “military areas” to prevent sabotage or espionage.

After the order went into effect, Lt. General John L. DeWitt, in charge of the Western Defense Command, ordered approximately 127,000 people of Japanese descent who lived on the West Coast to report to assembly centers. This was roughly 90% of the U.S. Japanese population. Over 60% of them were born in the United States and were American citizens. From the assembly centers, they were transferred to hastily prepared camps in the interior of California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Arkansas.

Those who lived in the camps reported deeply traumatic experiences. Families were sometimes separated. People could only bring a few of their belongings and had to abandon the rest of their possessions. The camps were dismal: Many residents lived in crudely constructed shacks. The camps were also overcrowded. Privacy was difficult to come by.

Despite these hardships, internees built communities within the camps. Adults served in camp government and worked at a variety of jobs. Families planted gardens. Children attended school, played basketball against local teams, and organized Boy Scout troops.

Japanese Americans were essentially imprisoned. Minor violations of rules, like walking too close to the fence, could have severe consequences. They endured these hardships without due process: No internees had been convicted of sabotage or espionage.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL