Table of Contents |

How could so many different types of antibodies be encoded? And what about the many specificities of T cells? There is not nearly enough DNA in a cell to have a separate gene for each specificity. The mechanism was finally worked out in the 1970s and 1980s using the new tools of molecular genetics.

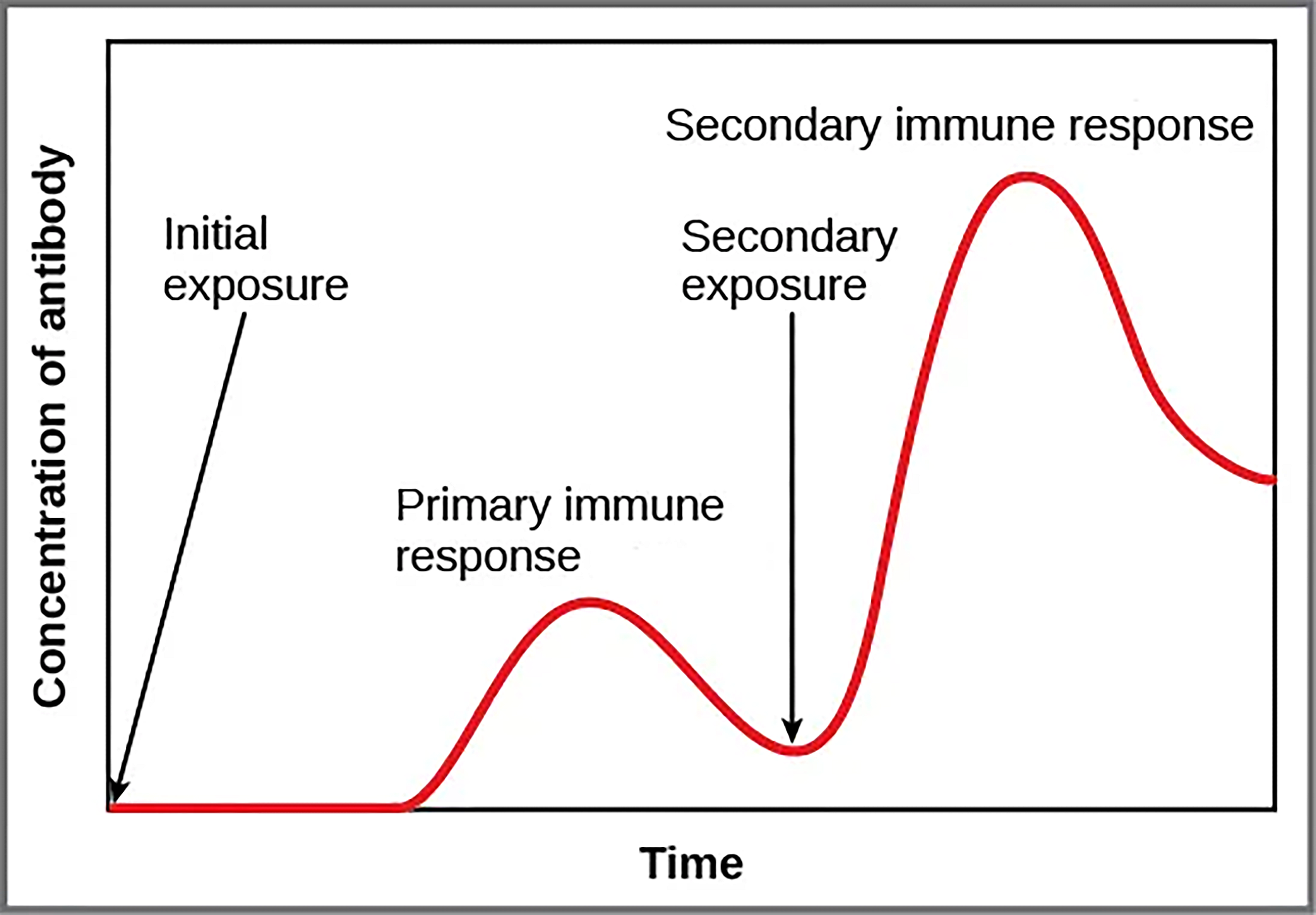

The immune system’s first exposure to a pathogen is called a primary adaptive response. Symptoms of a first infection, called primary disease, are always relatively severe because it takes time for an initial adaptive immune response to a pathogen to become effective.

Upon re-exposure to the same pathogen, a secondary adaptive immune response is generated, which is stronger and faster than the primary response. The secondary adaptive response often eliminates a pathogen before it can cause significant tissue damage or any symptoms. Without symptoms, there is no disease, and the individual is not even aware of the infection. This secondary response is the basis of immunological memory, which protects us from getting diseases repeatedly from the same pathogen. By this mechanism, an individual’s exposure to pathogens early in life spares the person from these diseases later in life.

A third important feature of the adaptive immune response is its ability to distinguish between self-antigens, those that are normally present in the body, and foreign antigens, those that might be on a potential pathogen. The immune system has to be regulated to prevent wasteful, unnecessary responses to harmless substances, and more importantly, so that it does not attack “self.” The acquired ability to prevent an unnecessary or harmful immune response to a detected foreign substance known not to cause disease, or self-antigens, is described as immune tolerance.

As T and B cells mature, there are mechanisms in place that prevent them from recognizing self-antigens, preventing a damaging immune response against the body. The primary mechanism for developing immune tolerance to self-antigens occurs during the selection of weakly self-binding cells during T and B lymphocyte maturation. There are populations of T cells that suppress the immune response to self-antigens and that suppress the immune response after the infection has cleared to minimize host cell damage induced by inflammation and cell lysis.

Immune tolerance is especially well developed in the mucosa of the upper digestive system because of the tremendous number of foreign substances (such as food proteins) that antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the oral cavity, pharynx, and gastrointestinal mucosa encounter. Immune tolerance is brought about by specialized APCs in the liver, lymph nodes, small intestine, and lung that present harmless antigens to a diverse population of regulatory T (Treg) cells, specialized lymphocytes that suppress local inflammation and inhibit the secretion of stimulatory immune factors. The combined result of Treg cells is to prevent immunologic activation and inflammation in undesired tissue compartments and to allow the immune system to focus on pathogens instead.

However, these mechanisms are not 100% effective, and their breakdown leads to autoimmune diseases, which will be discussed in a later lesson.

Immunity to pathogens and the ability to control pathogen growth so that damage to the tissues of the body is limited can be acquired by (1) the active development of an immune response in the infected individual (active immunity) or (2) the passive transfer of immune components from an immune individual to a nonimmune one (passive immunity). Both active and passive immunity have examples in the natural world and as part of medicine.

Active immunity is the resistance to pathogens acquired during an adaptive immune response within an individual. Naturally acquired active immunity occurs in response to a pathogen, whereas artificially acquired active immunity involves the use of vaccines. A vaccine is a killed or weakened pathogen or its components that, when administered to a healthy individual, leads to the development of immunological memory (a weakened primary immune response) without causing much in the way of symptoms.

Passive immunity arises from the transfer of antibodies to an individual without requiring them to mount their own active immune response. Naturally acquired passive immunity is seen during fetal development. IgG antibodies are transferred from the maternal circulation to the fetus via the placenta, protecting the fetus from infection and protecting the newborn for the first few months of its life. As already stated, a newborn benefits from the IgA antibodies it obtains from milk during breastfeeding. The fetus and newborn thus benefit from the immunological memory based on the pathogens the pregnant person has been exposed to. In medicine, artificially acquired passive immunity usually involves injections of immunoglobulins, taken from animals previously exposed to a specific pathogen. This treatment is a fast-acting method of temporarily protecting an individual who was possibly exposed to a pathogen. The downside to both types of passive immunity is the lack of the development of immunological memory. Once the antibodies are transferred, they are effective for only a limited time before they degrade.

|

Acquired Immunity Immunity that develops during your lifetime | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Immunity | Passive Immunity | |||

|

Natural: Antibodies developed in response to an infection |

Artificial: Antibodies developed in response to a vaccination |

Natural: Antibodies received from birthing parent, through breast milk |

Artificial: Antibodies recieved from medicine, from a gamma globulin injection or infusion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. (2) "BIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/BIOLOGY-2E. (3) "CONCEPTS OF BIOLOGY" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/CONCEPTS-BIOLOGY. LICENSING (1, 2, & 3): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed 24 August 2023.