Table of Contents |

The artwork covered in this lesson is from 1913 to 1948, as highlighted in the timeline below. The geographical locations of these artworks are as follows:

Surrealism was a 20th-century art movement and style defined by its exploration of the subconscious mind through vivid and dreamlike imagery.

One technique that Surrealists used was known as an exquisite corpse drawing. With this technique, one person folds a piece of paper into sections like an accordion such that the other sections are hidden from view. Then that person starts the drawing, leaving lines indicating where the drawing ends. The next person takes those lines and continues the drawing. Then it is passed on to the next person, and so on and so forth, until the drawing is finished. This is meant to be a technique that will expose the inner workings of the unconscious mind.

The Dada poet André Breton started the Surrealist movement. Breton was inspired by the metaphysical painting The Red Tower, shown here:

View The Red Tower.

View The Red Tower.

The painting was created by the Greek-born artist Giorgio de Chirico, a pioneer of the Surrealist art movement. Early in his career, de Chirico developed a distinctive style characterized by desolate landscapes, anachronistic imagery, and dramatic contrasts between light and shadow—all of which are vividly present in this work.

De Chirico’s compositions evoke a profound sense of mystery and unease, drawing the viewer into a world that feels both familiar and alien. His use of architectural forms, such as towers and classical facades, set against eerily empty plazas creates an unsettling atmosphere where time stands still.

These techniques are not merely aesthetic choices; they serve a deeper purpose in de Chirico’s work. By distorting perspective and placing incongruous elements together, he aims to depict the unseen imagery of the mind—the subconscious thoughts, memories, and fears that linger beneath the surface of everyday consciousness. In doing so, de Chirico invites viewers to question their perceptions of reality and to explore the enigmatic spaces within their own minds.

This approach profoundly influenced the development of Surrealism, as artists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte drew inspiration from de Chirico’s ability to merge the mundane with the mysterious. His work continues to resonate as a powerful exploration of the human psyche, challenging us to confront the unknown and embrace the ambiguities of existence.

The techniques used in Surrealism had a strong influence on artists such as Salvador Dalí. Dalí was also influenced by the works of Sigmund Freud in the field of psychology and interpretations of the unconscious mind.

This painting by Dalí, called The Persistence of Memory, is perhaps the most famous example of Surrealist work.

View The Persistence of Memory.

View The Persistence of Memory.

Observe the melting, drooping clocks that drape and slide off surfaces, defying the laws of physics and time. These surreal images have sparked countless interpretations, yet their meaning remains elusive and perplexing. This ambiguity might be precisely the point. Surrealists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte sought to capture the disjunction between reason and the irrational, using the dreamlike imagery of the unconscious mind to challenge conventional logic and reality.

In their work, the ordinary is transformed into the extraordinary as familiar objects are depicted in strange, unnatural ways. Dalí’s melting clocks, for instance, distort our perception of time, turning something as rigid and structured as a clock into a fluid, organic form. This surreal transformation suggests that time, much like the subconscious, is malleable, unpredictable, and beyond our control.

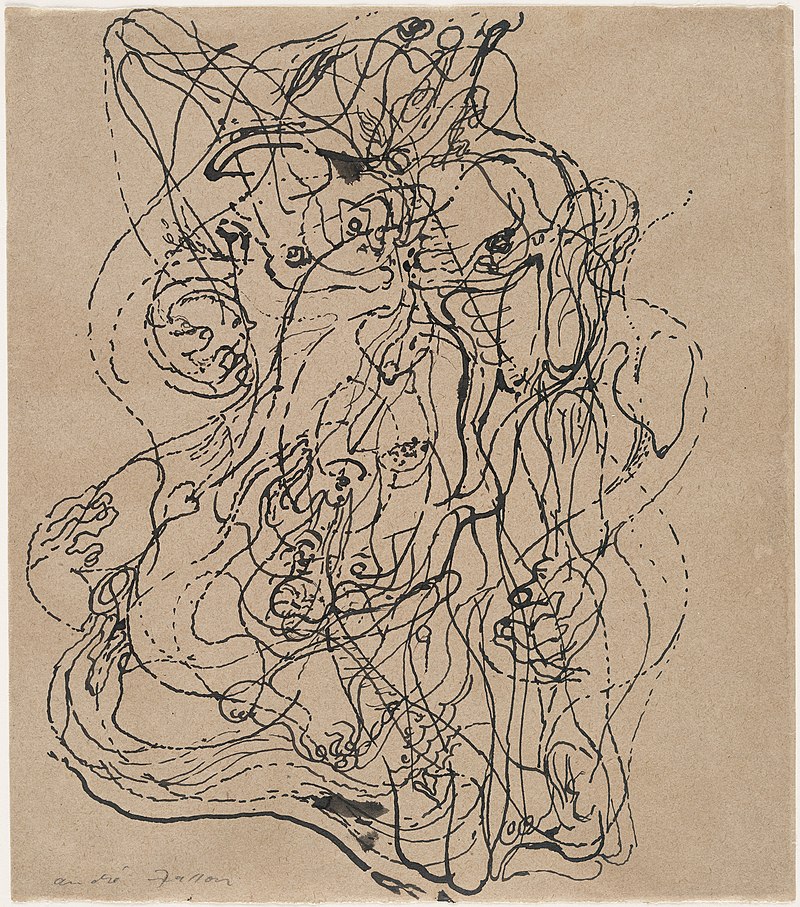

Compare the above works of art to this next image, which is an ink-on-paper drawing from the French artist André Masson.

Automatic Drawing

Museum of Modern Art, New York

1924

Ink on paper

André Breton, in his Surrealist Manifesto, defined Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism.” This concept manifests in various forms, such as automatic painting, automatic writing, and in this instance, automatic drawing. Unlike the reactive imagery of Dalí and Magritte, which illustrates the unconscious mind, Masson’s automatic drawing takes a more proactive approach. His technique seeks to liberate the unconscious by translating its spontaneous flow directly onto the canvas, akin to the process of automatic writing. Through this method, Masson aimed to tap into the depths of the psyche, allowing the subconscious to express itself freely without the constraints of rational thought.

Surrealism was not limited to painting or drawing. Sculptures existed as well in this form of art. Although the artist Méret Oppenheim has historically been suggested as rather indifferent to the symbolism of her work, many interpretations from critics have been posited.

View Object (Breakfast in Fur).

View Object (Breakfast in Fur).

Given the widespread prevalence of Freudian psychological symbolism at the time, critics have noted sexual undertones in elements such as the spoon’s phallic shape. They also highlight the cup’s symbolism, interpreting it as representing female genitalia and associating it with the human mouth. However, Oppenheimer herself stated that her intention was solely to explore the contrast of material textures, inspired by a conversation she had with Pablo Picasso.

This next painting, by Belgian artist René Magritte, is more than just an image of a pipe. In fact, beneath the depiction of a pipe, Magritte writes “This is not a pipe” in French to confound us even more.

View The Treachery of Images.

View The Treachery of Images.

Magritte’s painting serves as a profound philosophical inquiry into the nature of reality and representation. His message is straightforward yet thought-provoking: This is not a pipe; rather, it is an image of a pipe. Likewise, the word “pipe” is not the object itself but merely letters assigned a certain meaning. By making this distinction, Magritte challenges our assumptions about what is real and what is merely a representation. He compels us to consider the difference between the physical object and its depiction, emphasizing that the image, no matter how accurate, is not the object itself. The painting invites viewers to reflect on the complexities of perception and the ways in which art can blur the lines between reality and illusion.

In 1940, André Breton traveled to Mexico and, in a sweeping gesture, declared the entire country as the ultimate embodiment of Surrealism. During his visit, he met with Frida Kahlo and, in the process, claimed her art as part of the Surrealist movement. However, Kahlo herself never identified as a Surrealist. She insisted that her paintings were not imaginative or fantastical but were instead honest depictions of life as she experienced it.

Consider Kahlo’s painting entitled What the Water Gave Me below. Through this work, we see her unique perspective—an intricate blend of personal reality, memory, and emotion—that defies easy categorization. Kahlo’s art stands apart as a vivid and deeply personal exploration of her inner world.

What the Water Gave Me

Collection of Daniel Filipacchi, Paris

1922

Oil on canvas

Her paintings reveal that what might initially appear as disconnected mental imagery is a deeply personal narrative. In works like What the Water Gave Me, the central theme is an intimate reflection of Kahlo’s own life, filled with symbolic representations of past and present experiences. The imagery unfolds like a montage of memories as if a lifetime is flashing before the eyes of the central figure, who is interpreted as Frida herself, poised on the brink of drowning in the water.

In this context, the painting becomes a poignant portrayal of human introspection and sorrow, where the surreal elements are not mere flights of fancy but rather a profound expression of Kahlo’s inner world, shaped by pain, memory, and a relentless quest for understanding her own existence.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.