In most cases, free markets function wonderfully with little or no government intervention. Producers have a profit motive to provide consumers with what they want at prices they are willing to pay.

Therefore, unregulated free markets generally provide the best outcome, which is an idea to keep in mind as we continue this discussion.

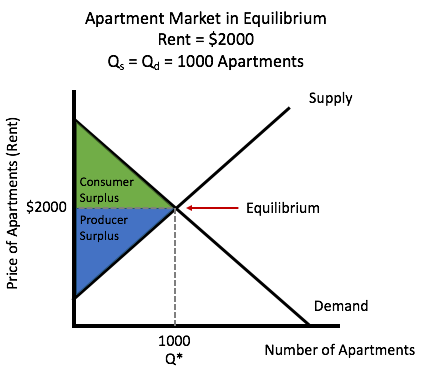

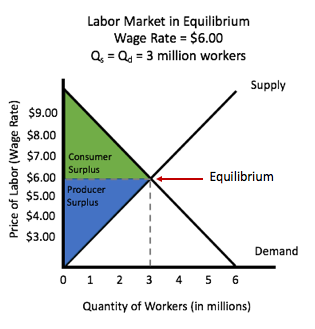

Now, when we refer to overall welfare being maximized, we mean that when the market reaches equilibrium, both consumers and producers are better off. In addition, there is no deadweight loss, which we will cover later in the lesson.

We can use welfare analysis to compare consumer and producer surplus before and after government intervention. Now, when the government does not intervene, the consumer and producer surplus will be maximized.

However, we know that sometimes the government does intervene, and it is important to be able to measure this impact on consumers, producers, and society as a whole.

EXAMPLE

If, for example, you were willing to pay $100 to see a concert, but you bought a ticket from someone for $60, then you enjoyed a consumer surplus of $40.On the other hand, producer surplus is the difference between the actual payment for a good and the least amount that producer would have agreed to receive for the good.

EXAMPLE

Suppose you are selling baseball cards on eBay, and you decide that you are willing to accept as little as $25 for one of the cards. Then, someone offers you $40 for the card. In this case, you enjoyed a producer surplus of $15.Let's begin this section with an example. This graph represents the market for apartments, assuming a rather expensive city like New York City.

Note the point of equilibrium in the market. According to this graph, if we allowed the market to achieve equilibrium, then the equilibrium rent would be $2,000, and there would be 1,000 apartments supplied and demanded at that point.

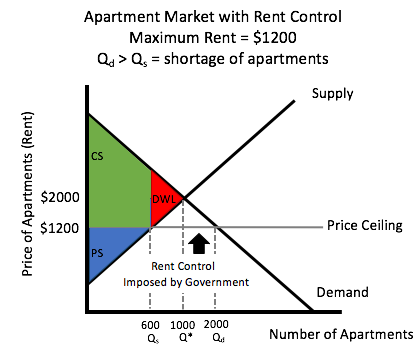

However, many people are unable to afford this high rent. Often the government will step in and control rents, imposing a maximum price that landlords are allowed to charge.

Notice, though, the consumer surplus in the green area. This area represents all the people who were willing to pay more than $2,000. In addition, the producer surplus area represents all of the landlords who were willing to rent for less.

Now, suppose the government sets a maximum price of $2,500, meaning that landlords cannot charge any higher rent than $2,500 per month. This action would set a ceiling. Now, you might think that a ceiling should be above equilibrium, because technically speaking, a ceiling is above one's head, but would that have any market impact at all?

In reality, landlords only want to charge $2,000, because that is the price that clears the market. If they set a maximum price above $2,000, it would actually have no market impact.

In this case, if landlords are mandated not to charge more than $2,500, it will not have any impact, because they only want to charge $2,000. This is what is called a non-binding constraint, a pricing constraint that does not preempt market equilibrium.

A binding constraint, on the other hand, is different. This is typically a regulatory constraint that does preempt market equilibrium by setting a different price level, known as a price ceiling or a price floor. In this case, the market cannot establish equilibrium.

Well, if this is the maximum that landlords are allowed to charge, notice that the market cannot be in equilibrium anymore. The quantity demanded at this price is at 2,000, but the quantity supplied is lower now, because, at lower prices, landlords do not want to supply their apartments. Therefore, we have what is called a shortage of apartments, where the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied.

Also, notice what happens with consumer surplus (green area) and producer surplus (blue area) on the graph. Consumer surplus grows slightly, but only for those people who can find apartments. Producer surplus, on the other hand, shrinks significantly.

In addition, the red triangle represents what used to be enjoyed by both consumers and producers, known as a deadweight loss to society, which we will define shortly. Basically, that is what is lost between consumer and producer surplus to society whenever the government imposes a binding price ceiling.

However, the government does not allow companies to pay workers $6 per hour, because of the minimum wage law. Now, if the labor market were allowed to be in equilibrium, there would not be a deadweight loss to society. Consumer and producer surplus would be maximized as shown by the green and the blue triangles below.

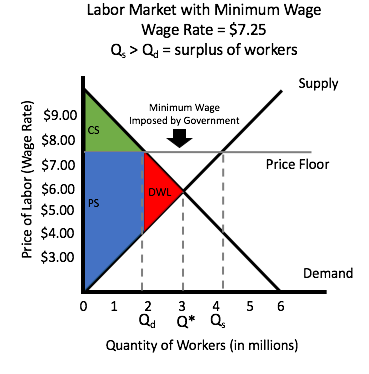

However, as mentioned, the government does set a price floor, which is another example of a binding constraint. A price floor is a minimum amount that must be paid for something. So, the current minimum wage of $7.25 is above equilibrium. This is the lowest amount that employers can pay.

So, what happens when the market cannot establish equilibrium? Well, as you raise the price floor above equilibrium, the quantity supplied is greater. More workers are willing to supply their labor, but employers are less willing to hire. Therefore, the quantity demanded for labor falls, and there is now a gap. The quantity supplied being greater than the quantity demanded means we have a surplus of workers.

Notice in the graph that consumer surplus, the green triangle, is now much smaller. Producer surplus grows a bit, but once again you can see this red triangle, which used to be consumer and producer surplus. It is a deadweight loss to society because of this price floor being imposed.

This red area that represents deadweight loss is the change in total surplus. It is the sum of producer and consumer surplus that was lost, resulting from the imposition of a binding constraint, either a price ceiling or a price floor.

Source: Adapted from Sophia instructor Kate Eskra.