Table of Contents |

The artwork in this lesson is from 1916 to 1957. The geographical regions that will be covered in this lesson include the following:

Ukrainian artist Kazimir Malevich was the pioneering force behind the development of Suprematism, a radical art movement that sought to transcend the traditional boundaries of visual representation. The term “Suprematism” reflects Malevich’s belief that this new form of art would surpass all previous artistic traditions, establishing the “supremacy” of pure emotion in the visual arts. Unlike earlier movements that were often tied to the depiction of recognizable objects or narratives, Suprematism broke away from these conventions, embracing abstraction to its fullest extent. Malevich aimed to strip art down to its most fundamental elements—color, shape, and form—thereby creating a visual language that conveyed raw, unmediated experiences.

This approach led to an extremely minimalist aesthetic characterized by stark geometric forms, such as squares, circles, and lines, often set against a plain background. Suprematism’s minimalist ethos bore similarities to the De Stijl (Dutch for “the Style”) movement, which emerged around the same time in the Netherlands, though De Stijl focused more on the balance and harmony of form and color. Both movements sought to push the boundaries of what art could be, moving away from representational art and toward a universal visual language that could evoke deep responses without relying on the depiction of the physical world.

Malevich’s approach centered on reducing form to its most basic geometric shapes and colors while elevating the importance of feeling and emotion in art. He believed that by stripping away any ties to recognizable objects, his art could transcend the limitations of traditional forms. This universality of form was key to his vision—since the artwork wasn’t anchored to anything specific, it allowed each viewer to construct their own meaning. The abstract nature of his work invited individuals to connect with the painting in deeply personal ways, free from the constraints of predetermined interpretations.

EXAMPLE

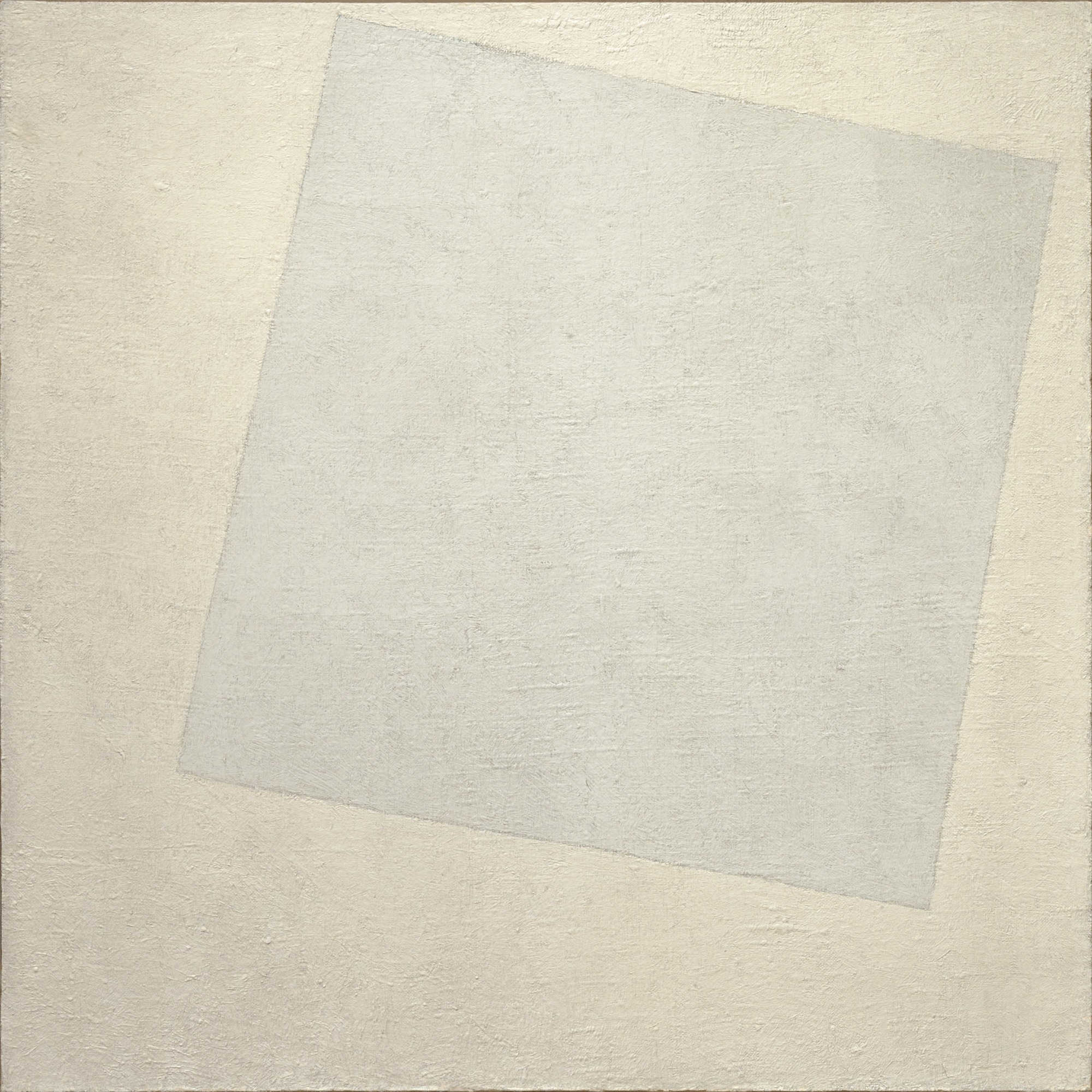

Below is an example of Malevich’s Suprematist Composition.

Throughout his career, Malevich continued to work toward achieving what he called a “zero point” in his artwork. Malevich’s concept of reaching a “zero point” in his compositions was a deliberate effort to distill art to its most fundamental elements—stripping away all excess until only the essence remained. This pursuit of purity aimed to reveal what he believed to be the core of artistic expression, where form and color exist in their most elemental state. By reducing his compositions to basic geometric shapes like squares and circles, Malevich sought to eliminate all distractions, focusing solely on the interplay of these forms and their emotional effect.

EXAMPLE

An example of this concept might be a black circle on a white background. Similarly, the canvas below, featuring squares painted in two nearly indistinguishable shades of white, illustrates this threshold. If you remove the slightly tilted square, you’re left with little more than a frame and an empty space.

While Suprematism was primarily focused on the visual arts, the development of Constructivism by the Ukrainian-born Soviet artist Vladimir Tatlin expanded the realm of abstraction into various artistic disciplines, including sculpture, design, and architecture. Constructivism played a significant role in the early Soviet Union, where it was deeply connected to the revolutionary ideals of the time. Initially, Constructivism had a utopian purpose, aimed at serving the needs of the revolution by creating art that was functional, utilitarian, and aligned with the principles of the new socialist society.

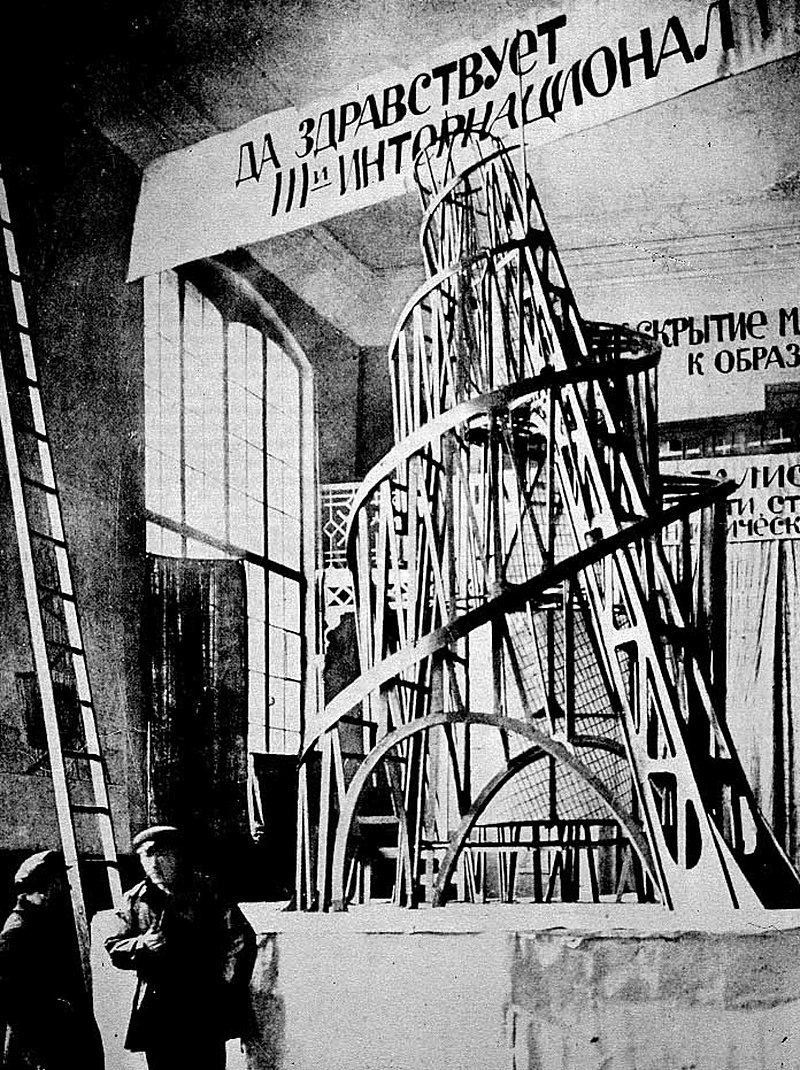

EXAMPLE

This monument to the Third International was a model built by Tatlin for a structure that was to eclipse the Eiffel Tower in terms of size and modernity. It parallels the formation of a new world order taking place in the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, the project never progressed beyond the conceptual stage for several reasons. One of the primary obstacles was the scarcity of materials—steel was in short supply in postwar revolutionary Russia. Additionally, the movement was eventually abandoned by the state, which deemed it too radical to support.

If you’re a fan of the band Franz Ferdinand, you may be familiar with this next image, as it inspired the cover art on their second major release. The Constructivist photographer Alexander Rodchenko, a student of Tatlin, was another pioneer in the art of photomontage. He inspired countless photographers in the decades to come with his unique approach to photography.

By capturing images from unconventional angles—such as from below or above the central figure—Rodchenko introduced a sense of disorientation and dissociation between the viewer and the subject. This technique, known as distanciation, intentionally made the familiar appear unfamiliar, challenging viewers to see everyday objects and scenes in a new light. By altering perspective, Rodchenko disrupted the traditional way of seeing, forcing the audience to engage more critically with the imagery. This approach not only revolutionized the art of photography but also underscored the Constructivist goal of breaking away from established norms to explore new artistic possibilities. Distanciation became a powerful tool for conveying the complexities of modern life, making the ordinary extraordinary by altering the viewer’s perception.

EXAMPLE

There is also the apparent irony of using capitalistic advertising, as in his work below, to extend the socialist agenda of the government.

Naum Gabo was another influential Constructivist whose artistic vision grew as he absorbed a broader range of ideas from beyond his native country of Russia. He became a pioneer in kinetic art, creating works that incorporated movement, and explored new dimensions of artistic expression. Drawing inspiration from figures like Kandinsky, Gabo embraced abstraction with the aim of evoking a spiritual experience through his creations. He sought to explore the concept of space, not by adding mass but by reducing it, creating a sense of openness and fluidity in his works. This approach allowed him to redefine the boundaries of sculpture and art, emphasizing the interplay between form, movement, and the space surrounding his objects.

EXAMPLE

Below is Gabo’s untitled sculpture, nicknamed Stylized Flower, from 1957.

Gabo immersed himself in academic lectures, where he became acquainted with Einstein’s revolutionary theories on space, time, and relativity. These scientific concepts profoundly influenced his artistic development, guiding him toward a style that transcended the traditional three dimensions of conventional art. Gabo’s work began to incorporate the fourth dimension—time—into his sculptures, leading to the creation of sculptures that were not just static forms but dynamic experiences.

In the spirit of simplification, De Stijl is fundamentally about reducing all forms to rectilinear shapes and lines and limiting color to the primary colors—red, blue, and yellow—plus black and white.

Theo van Doesburg, a versatile and influential artist, is widely regarded as the founder of De Stijl. Yet, he was not the movement’s only key figure. Around 1915, Van Doesburg met Piet Mondrian in Amsterdam, and together they worked to refine the De Stijl aesthetic. Van Doesburg remained the most active and vocal proponent of the group, writing a manifesto that articulated the philosophy behind the movement. He emphasized the creation of a universal style that could be adopted globally—one that deliberately suppressed natural forms and representations in favor of pure abstraction.

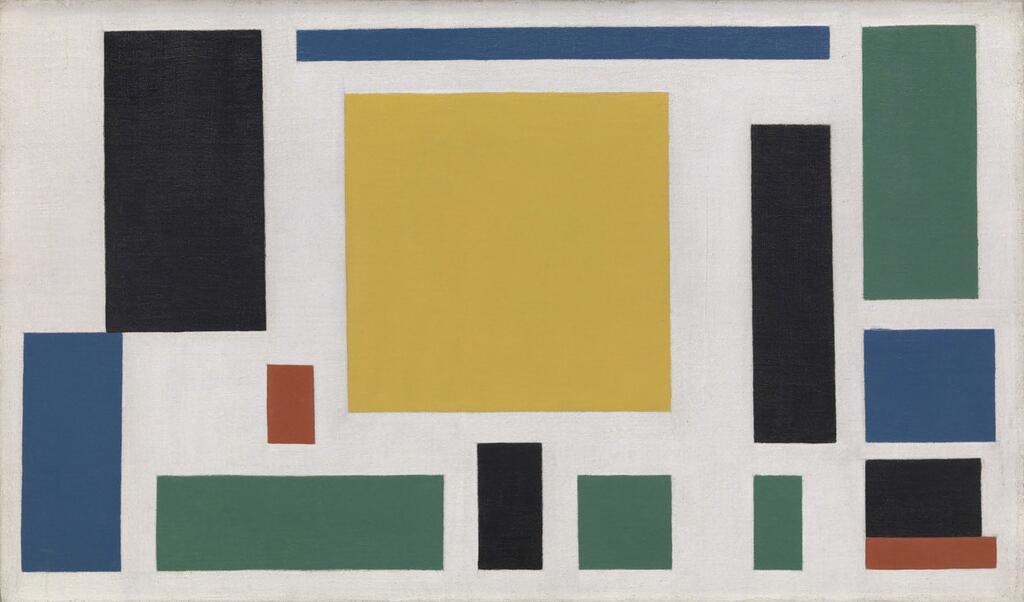

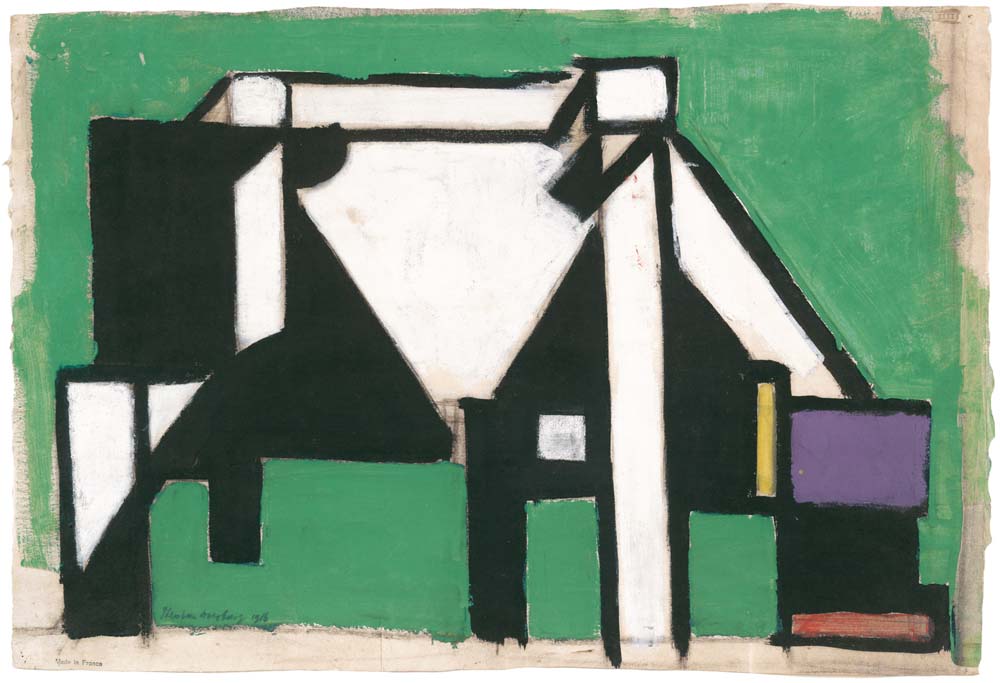

Below is an excellent example of the suppression of natural form. This painting, called Composition VIII, or The Cow, is the De Stijl artist’s interpretation of an actual cow.

Composition VIII (The Cow)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Circa 1918

Oil on canvas

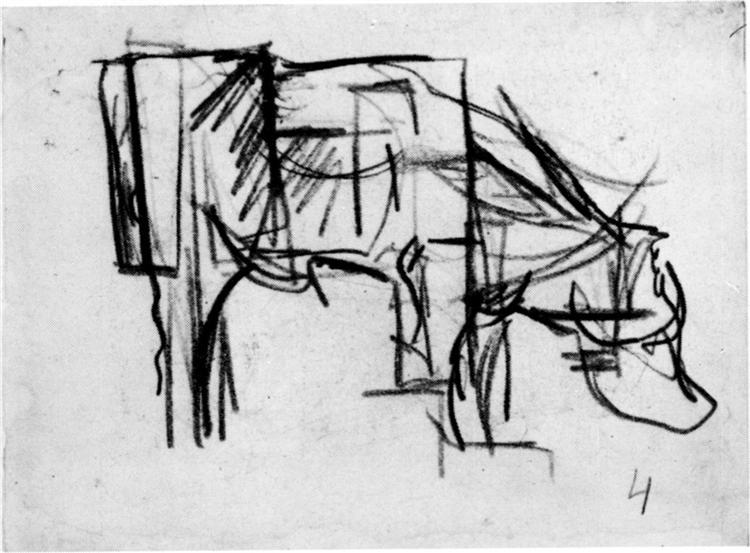

Let’s explore the transition from natural to abstract by examining Van Doesburg’s study drawings for this painting. Interestingly, he worked in reverse, beginning with a naturalistic image and progressively distilling it into its basic geometric shapes.

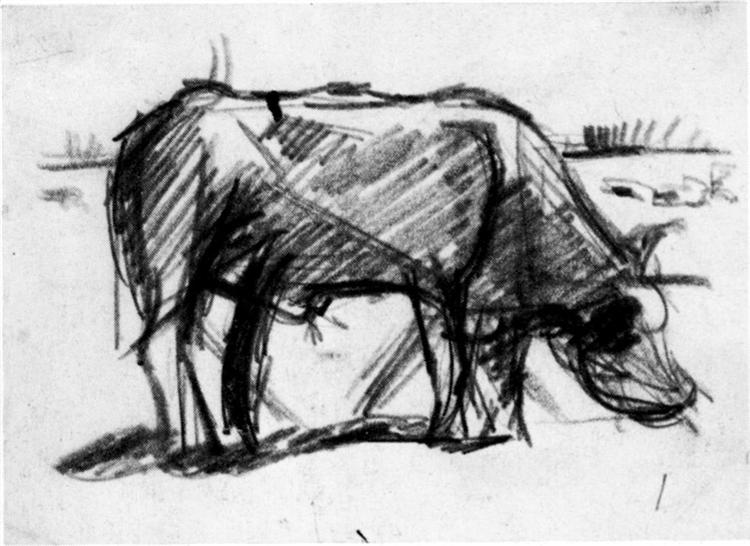

He starts with a cow, simply enough:

Study for Composition VIII (The Cow)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

1917

Graphite on paper

In the next image, he deconstructs the cow’s form into a series of interconnected geometric shapes—rectangles, triangles, and subtle hints of squares. The result still resembles a cow:

Study for Composition VIII (The Cow)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

In the next image, he takes the reduction even further by incorporating solid blocks of primary color. Despite the increased simplification, the essence of the cow remains recognizable:

Study for Composition VIII (The Cow)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

1917

Tempura, oil, and charcoal on paper

In the final composition, Van Doesburg separates the geometric shapes, allowing them to float independently of one another. While the direct representation of the cow is lost in the process, you can still trace his journey to this conclusion, which in a sense, brings the artwork back to its foundational beginnings.

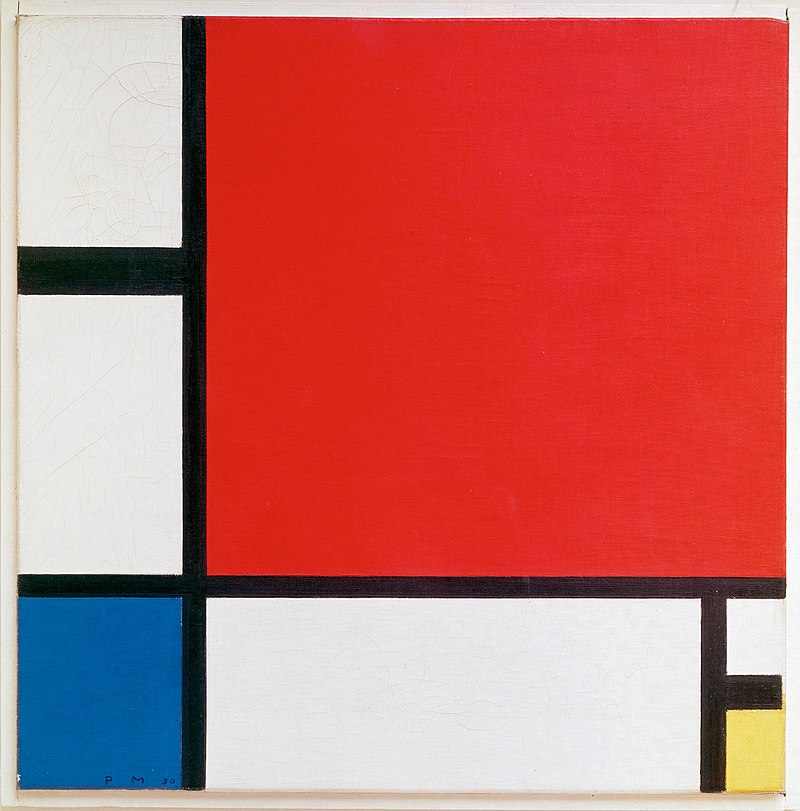

Piet Mondrian’s paintings are the epitome of De Stijl in its purest form, particularly in their strict adherence to the movement’s aesthetic principles. Mondrian reached this level of abstraction after years of artistic development. After meeting Theo van Doesburg around 1915, he returned to Paris, France, where he encountered Cubism. While Mondrian identified with the movement, he felt that Cubism didn’t go far enough in reducing forms to pure abstraction, as evident in the example shown here:

Composition II in Red, Yellow, and Blue

Kunsthaus, Zürich

1930

Oil on canvas

This composition by Mondrian features asymmetry—even the black lines in the composition are of different lengths.

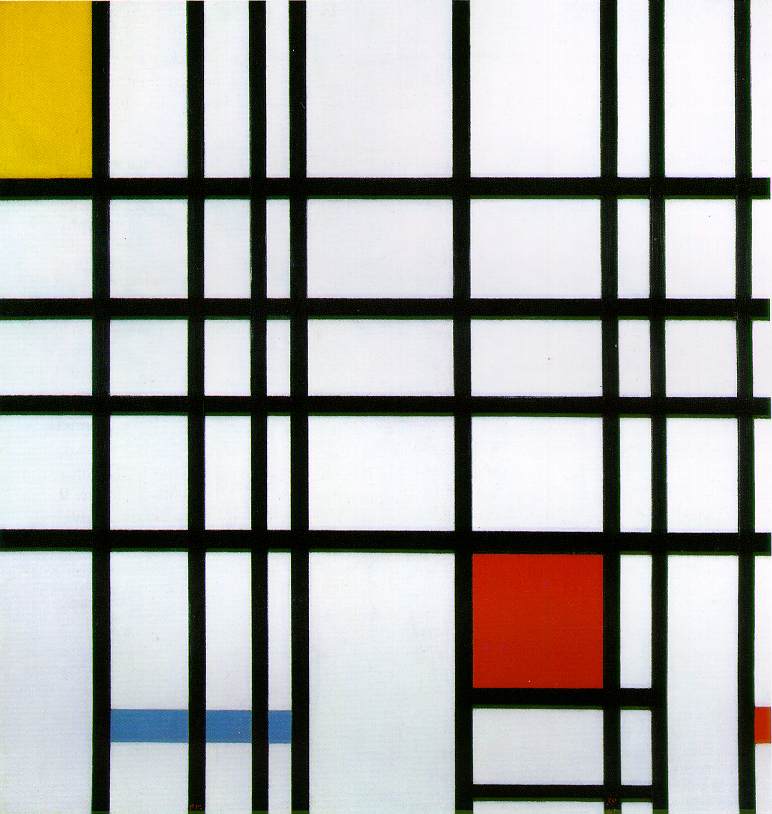

Mondrian spent many years in Paris, progressively refining his visual style until he achieved something like this:

Composition With Yellow, Blue, and Red

Tate, London

1937–1942

Oil on canvas

Notice the thick, black, straight lines on a white background with bold blocks of evenly or carefully positioned color.

De Stijl was not just an artistic style. It was also present in architecture and design, although not to the extent of movements such as Arts and Crafts, for example. Gerrit Rietveld emerged as the most important figure in these areas and took the visual aesthetic of De Stijl to its three-dimensional conclusion.

One of his most iconic designs is the chair shown here, which recalls Mondrian’s paintings but in three dimensions.

Red and Blue Chair

Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

1923

Painted wood

It’s a reduction of the chair’s basic elements—rectangular planes and solids—and is painted in only four colors.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.