Table of Contents |

In addition to millions of deaths worldwide and the emotional toll on everyone, the Covid-19 pandemic that began in 2020 is a perfect storm for supply chain problems that peaked in the fall of 2021 but are still being felt as of the writing of this tutorial in 2024. While the previous tutorial focused on the bullwhip effect, where over-ordering ripples up the supply chain, the supply chain crisis of the 2020s is one of shortages that cause problems down the supply chain.

In February to March of 2020, the world essentially shut down as people responded to the deadly coronavirus with stay-at-home orders and lockdowns. The initial ripples in the supply chain were a glut of purchases on home necessities like toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and other disposable goods, particularly ones related to health and hygiene. As people saw that the shelves were clearing, they were even more motivated to “stock up” when they had the luck of finding some in the store, taking more than they usually would. Such behavior would normally lead to a bullwhip effect as stores restocked. However, the special circumstances of the pandemic meant that after this initial run, stores struggled to maintain stock and, knowing of the prevailing shortages, people continued to over-purchase when they did see these goods on the shelf. You may recall signs posted that customers were limited to purchasing five or fewer packages of toilet paper, for example, to stem the problem.

Meanwhile, the need for high inventories of personal protective equipment (PPE) like masks, respirators, and gloves created immediate shortages by healthcare workers and homes alike. Similar to home necessities, these shortages continued throughout the pandemic, though it was due to an unusually high need for the supplies and not due to overpurchasing.

As the lockdown continued, there was also a surge in purchases of home electronics and other recreational items, since people were trying to find ways to spend their leisure time in isolation. Animal shelters saw a huge rise in pet adoptions, since many families decided it was the perfect time to train a puppy or introduce a new cat to their household. Impulse online purchasing was common for people who still had steady revenue and were spending less money on travel and entertainment. This spike in purchasing led to direct and indirect shortages. Home electronics were in short supply, as was anything else with microchips, including vehicles, which shortage lasted for years. There was a shortage of pet food due to the surge in new pets. There was suddenly a shortage of jewelry and other luxury goods.

Why did these surges in purchasing not lead to a bullwhip effect? Because manufacturing slowed due to stay-at-home orders and other causes. Even for industries considered “essential” by stay-at-home orders, production slowed due to worker illness, shortages of supplies, and transportation hampered by the sudden massive increase in package delivery services. Transportation limitations affected both inputs and outputs. So, even though the orders to restock might have ordinarily led to overstocking at the distribution level and higher, throughout the pandemic and in the subsequent years, manufacturers simply tried to get back up to normal operating levels.

You can see in situations like these that supply chain shortages not only move up the supply chain, but also back down the supply chain, creating shortages of other goods that use the same materials, or simply become unavailable due to labor and transportation being redirected to emergency needs.

While Covid-19 and the aftermath of the pandemic constricted the supply chain across the spectrum of good and services, it was not directly responsible for all shortages. In fact, a number of other issues occurred, such as an unusually high number of extreme weather events like hurricanes and snowstorms, which affect any industries in those areas, as well as a need for supplies directly related to the storms, such as building materials. There was a labor shortage, particularly for low-wage jobs, as people were reluctant to go back to work. Transportation continued to falter, particularly international transportation, as ports could not “scale up” to the demand following the pandemic. Some shortages were due to very specific circumstances. In the fall of 2021, cream cheese and other dairy products were limited following a cyberattack on a single distributor in Wisconsin. In July of 2022, baby formula had extreme shortages following a recall of some products. These events did not alone trigger the shortages, but they worsened the post-pandemic shortages in those industries.

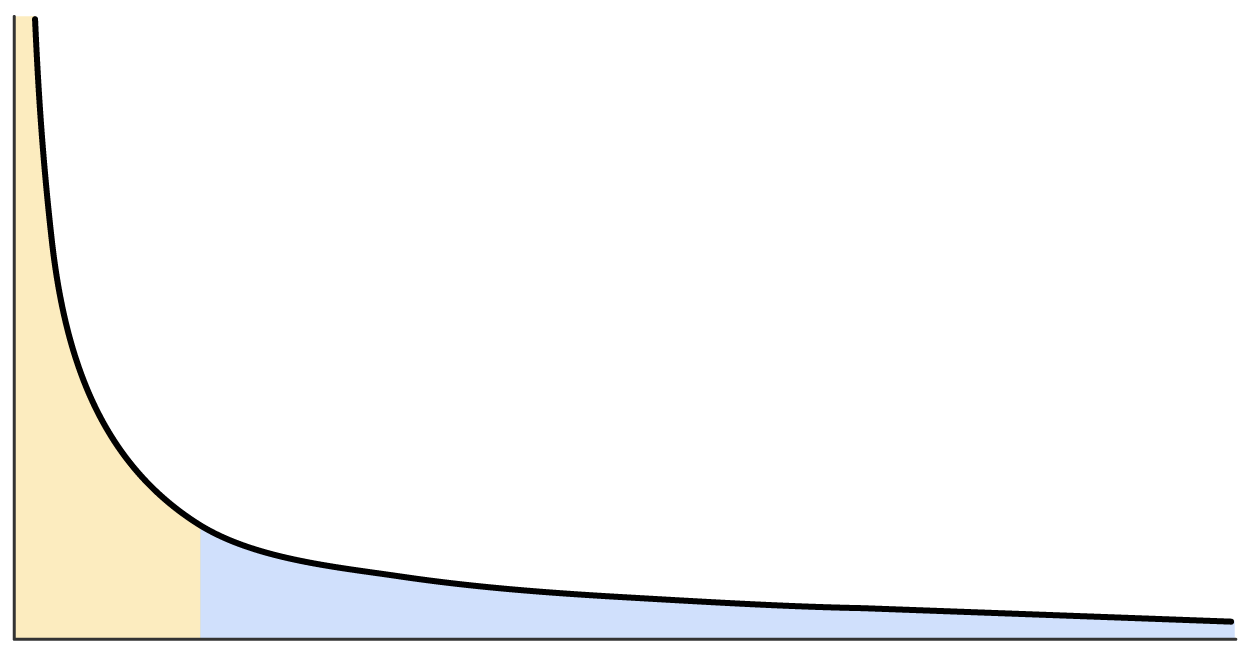

In any case, even 4 years after the pandemic, the long-term effects of a supply chain crisis were felt throughout the economy. A long tail refers to any phenomenon where distribution on a graph is high at the beginning and rapidly declines at first but then effectively plateaus for a long distribution on the right, making a tail. The x-axis for long tail effects is usually, but not always, a timeline. That is, some incident occurs a lot, then declines, but never stops completely...rather, it continues at a low degree.

Even smaller disruptions to the supply chain can have such a long tail effect, so a massive disruption to several supply chains may take a very long time to reach a “normal” state, and even then, enough change will have happened in the world for that to be a new “normal.”

The biggest impact of these shortages—and the longest lasting—has been on prices, particularly food prices. Again, the supply chain issues following the pandemic were only part of the problem, but the other issues like labor and tariffs would have been mitigated, or perhaps not noticed by consumers, if it weren’t for supply chain shortages. However, some of those issues were also triggered or escalated by the pandemic.

IN CONTEXT: The High Price of Snacks

As we learned in a previous tutorial, prices tend to go up as supplies go down. In this case the inflation can occur at every stop in the supply chain to have a particularly large effect on the consumer. At the beginning of the supply chain, a potato grower has to pay more for the laborers needed during the harvest and may also be reeling from higher prices on things like fertilizer, pesticide, and the gasoline that fuels the farm machinery. They thus mark up the price to the potato chip manufacturing center, who marks up the price to cover the higher price of potatoes, and marks it up further to cover a higher cost for labor, and perhaps the bags they are packed in. These costs are passed on to the distributor, who is similarly affected by a labor shortage and is further affected by a higher cost for gasoline. They finally reach the retailer, who must pay more for their stock and is also paying higher overhead for their stockers and cashiers, utilities, and other operating experiences. As you can see (and did see, recently), by the time they’re on the shelf, the chips may be twice the price they were a year ago.

While consumer over-purchasing during Covid-19, manufacturing slowdowns, and inflation may not have been predicted, there are still some things supply chain managers can do to reduce the impact of issues such as these.

Nike is another company that did well during the Covid-19 crisis. They were able to quickly make changes to their processes, such as focusing more on direct online sales rather than sales through retail stores. They shifted inventory destined for retail stores to warehouses so they could instead sell those products directly to consumers and offered discounts to encourage customers to buy shoes online. Their ability to pivot quickly was aided by advanced inventory management techniques such as digital tracking, risk management strategies, and a robust online presence. Their risk management strategies included data analytics to predict shortages, the use of multiple suppliers from different geographic areas, an inventory buffer (although there are downsides to this option, as we saw earlier), and having relationships with suppliers that allowed them to quickly make necessary changes to meet demand (Silver, 2021).

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.

REFERENCES

Palmer, A. (2020, September 29). How amazon managed the coronavirus crisis and came out stronger. CNBC.com. www.cnbc.com/2020/09/29/how-amazon-managed-the-coronavirus-crisis-and-came-out-stronger.html