Table of Contents |

Proteins are an important macronutrient and an essential component of our diets. Proteins are polymers of amino acids. Each amino acid contains a central carbon, a hydrogen, a carboxyl group, an amino group, and a variable R group. The R group specifies which class of amino acids it belongs to: electrically charged hydrophilic side chains, polar but uncharged side chains, nonpolar hydrophobic side chains, and special cases.

Proteins are one of the most abundant organic molecules in living systems and have the most diverse range of functions of all macromolecules. Proteins serve as transport helpers, storage, or membranes; or they may be toxins or enzymes. Each cell in a living system may contain thousands of proteins, each with a unique function. Their structures, like their functions, vary greatly. They are all, however, polymers of amino acids, arranged in a linear sequence.

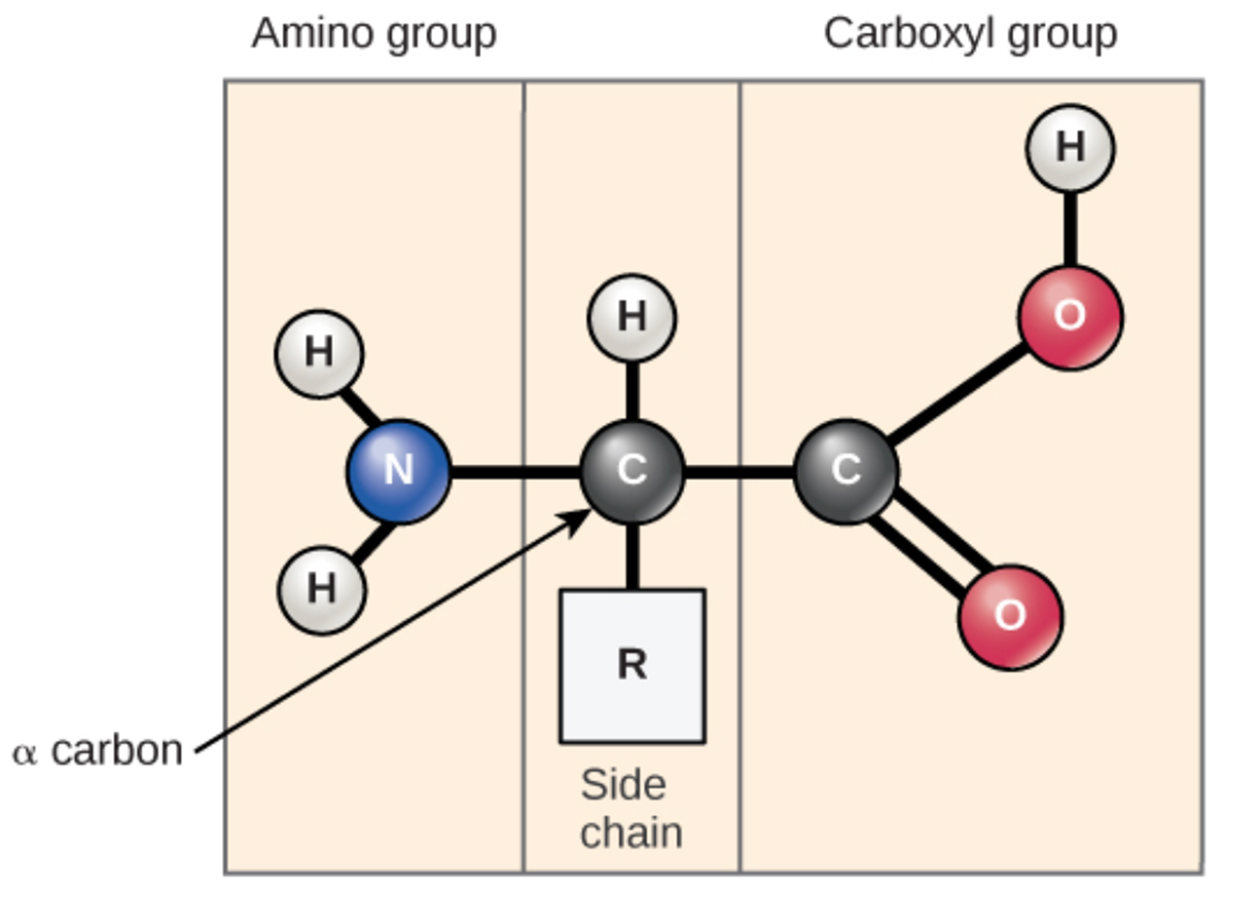

Amino acids are the monomers that make up proteins. Each amino acid has the same fundamental structure, which consists of a central carbon atom, also known as the alpha (α) carbon, bonded to an amino group (NH2), a carboxyl group (COOH), and to a hydrogen atom. Every amino acid also has another atom or group of atoms bonded to the central atom known as the R group (Figure 1).

The name “amino acid” is derived from the fact that they contain both amino group and carboxyl-acid-group in their basic structure. As mentioned, there are 20 amino acids present in proteins. Nine of these are considered essential amino acids in humans because the human body cannot produce them, and they are obtained from the diet.

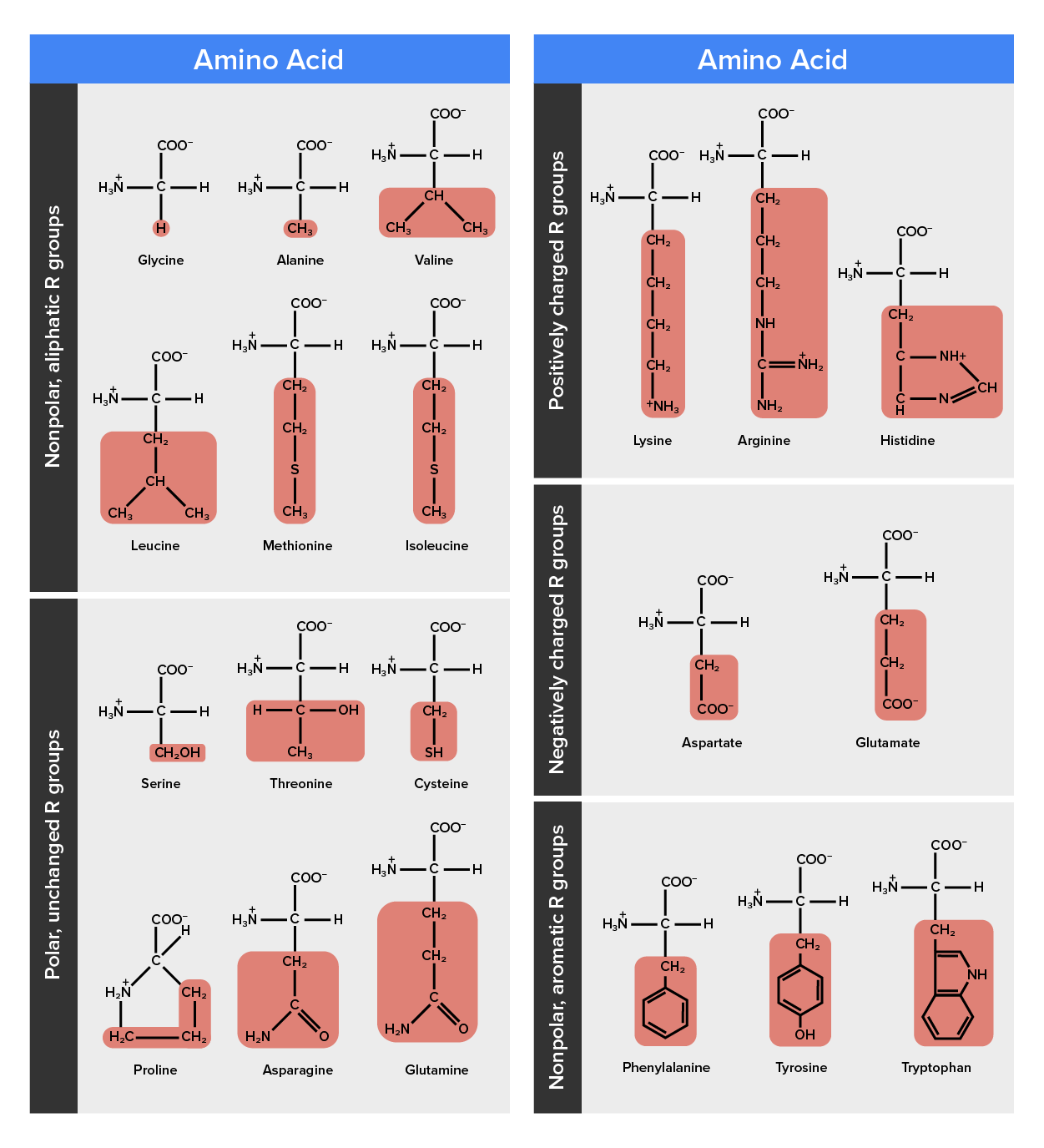

For each amino acid, the R group (or side chain) is different (Figure 2).

The chemical nature of the side chain determines the nature of the amino acid (that is, whether it is acidic, basic, polar, or nonpolar). For example, the amino acid glycine has a hydrogen atom as the R group. Amino acids such as valine, methionine, and alanine are nonpolar or hydrophobic in nature, while amino acids such as serine, threonine, and cysteine are polar and have hydrophilic side chains. The side chains of lysine and arginine are positively charged, and therefore these amino acids are also known as basic amino acids. Proline has an R group that is linked to the amino group, forming a ring-like structure. Proline is an exception to the standard structure of an amino acid since its amino group is not separate from the side chain (Figure 2).

Just as some fatty acids are essential to a diet, some amino acids are necessary as well. They are known as essential amino acids, and in humans they include isoleucine, leucine, and cysteine. Essential amino acids refer to those necessary for construction of proteins in the body, although not produced by the body; which amino acids are essential varies from organism to organism.

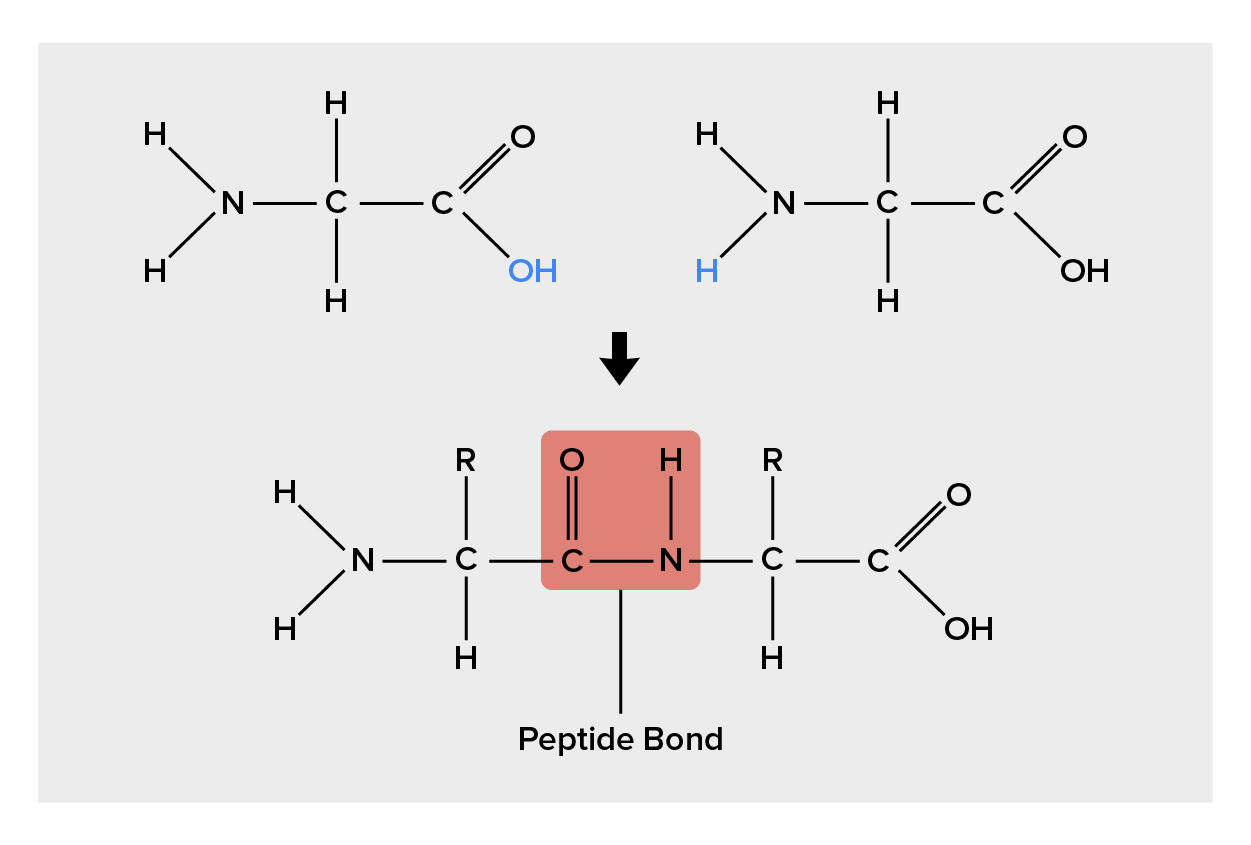

The sequence and the number of amino acids ultimately determine the protein’s shape, size, and function. Each amino acid is attached to another amino acid by a covalent bond, known as a peptide bond, which is formed by a dehydration reaction. The carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of the incoming amino acid combine, releasing a molecule of water. The resulting bond is the peptide bond (Figure 3).

IN CONTEXT

The products formed by such linkages are called peptides. As more amino acids join to this growing chain, the resulting chain is known as a polypeptide. Each polypeptide has a free amino group at one end. This end is called the N terminal, or the amino terminal, and the other end has a free carboxyl group, also known as the C or carboxyl terminal. While the terms polypeptide and protein are sometimes used interchangeably, a polypeptide is technically a polymer of amino acids, whereas the term protein is used for a polypeptide or polypeptides that have combined together, often have bound non-peptide prosthetic groups, have a distinct shape, and have a unique function. After protein synthesis (translation), most proteins are modified. These are known as post-translational modifications. They may undergo cleavage, phosphorylation, or may require the addition of other chemical groups. Only after these modifications is the protein completely functional.

As discussed earlier, the shape of a protein is critical to its function.

EXAMPLE

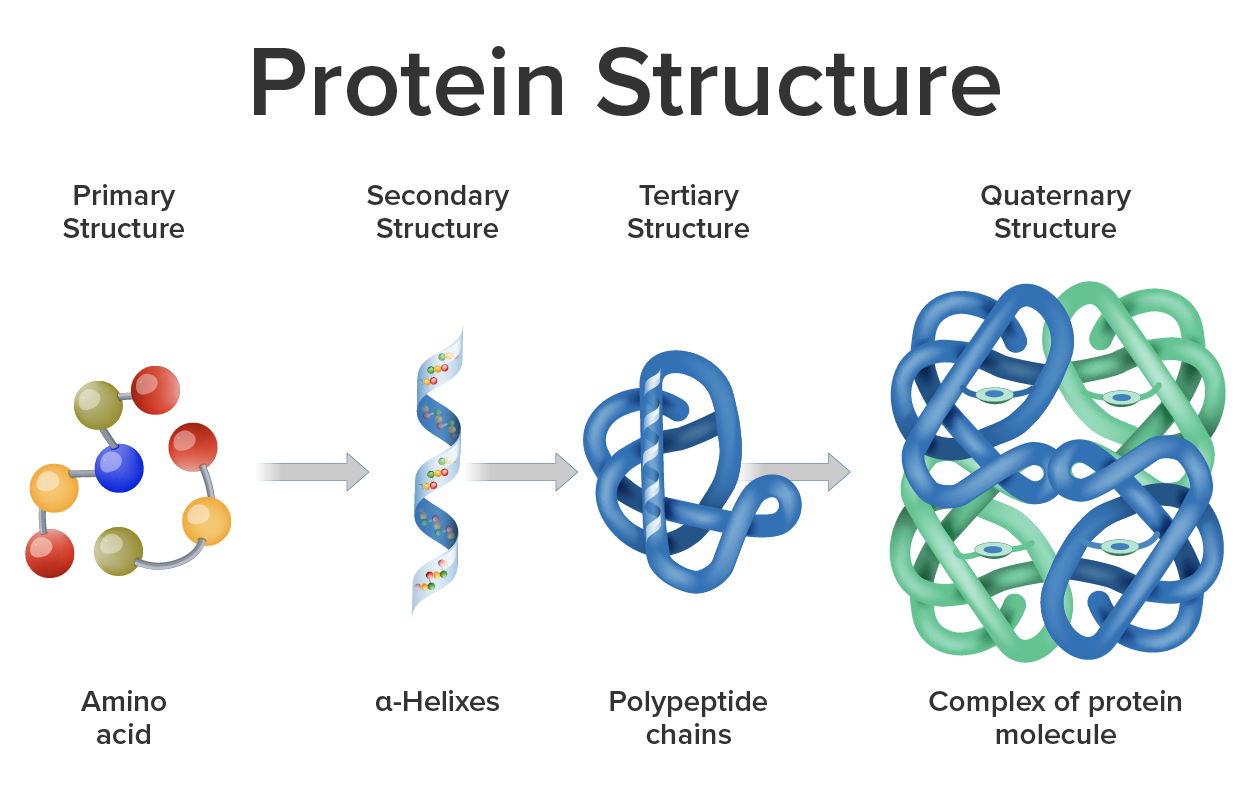

An enzyme can bind to a specific substrate at a site known as the active site. If this active site is altered because of local changes or changes in overall protein structure, the enzyme may be unable to bind to the substrate.To understand how the protein gets its final shape or conformation, we need to understand the four levels of protein structure: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

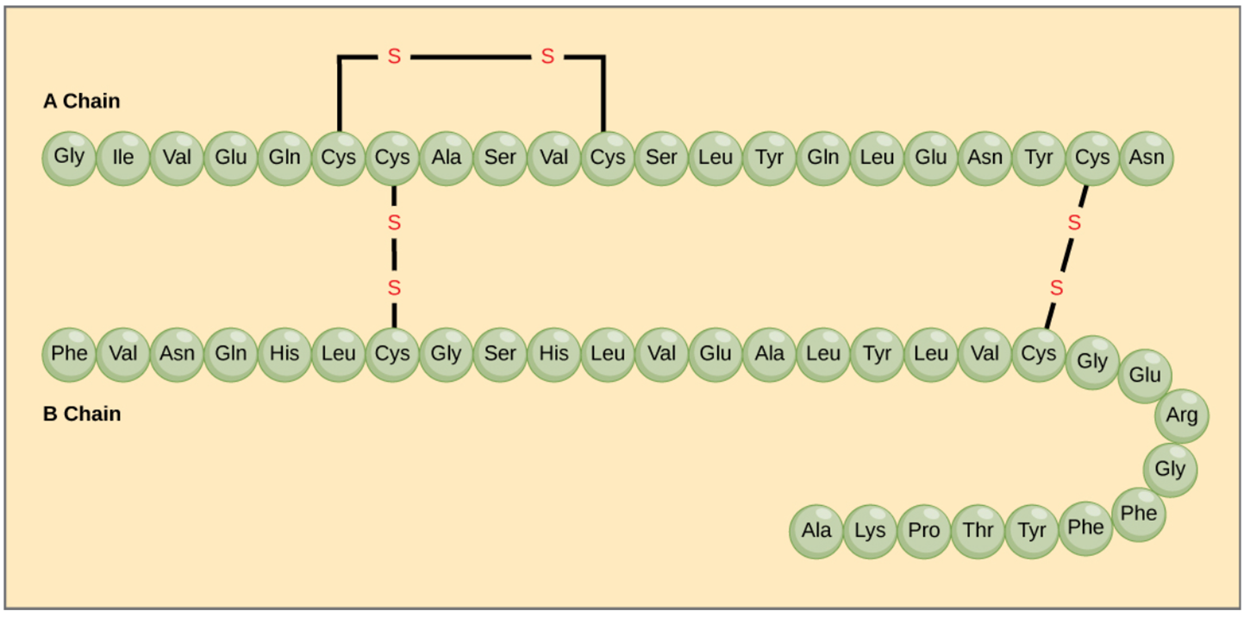

The primary structure of protein is the unique sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. For example, the pancreatic hormone insulin has two polypeptide chains, A and B, and they are linked together by disulfide bonds. The N terminal amino acid of the A chain is glycine, whereas the C terminal amino acid is asparagine (Figure 4). The sequences of amino acids in the A and B chains are unique to insulin.

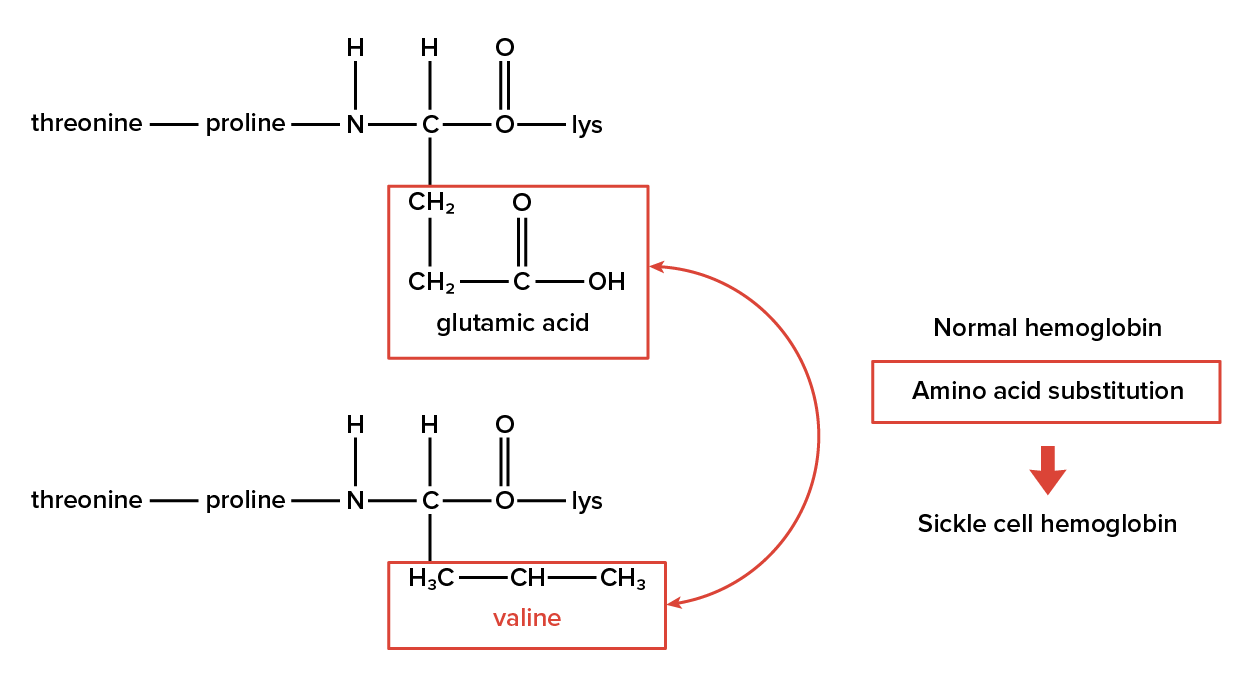

The unique sequence for every protein is ultimately determined by the gene encoding the protein. A change in nucleotide sequence of the gene’s coding region may lead to a different amino acid being added to the growing polypeptide chain, causing a change in protein structure and function. In sickle cell anemia, the hemoglobin β chain (a small portion of which is shown in Figure 5) has a single amino acid substitution, causing a change in protein structure and function.

Specifically, the amino acid glutamic acid is substituted by valine in the β chain. What is most remarkable to consider is that a hemoglobin molecule is made up of two alpha chains and two beta chains that each consist of about 150 amino acids. The molecule, therefore, has about 600 amino acids. The structural difference between a normal hemoglobin molecule and a sickle cell molecule—which dramatically decreases life expectancy—is a single amino acid of the 600. What is even more remarkable is that those 600 amino acids are encoded by three nucleotides each, and the mutation is caused by a single base change (point mutation), 1 in 1,800 bases.

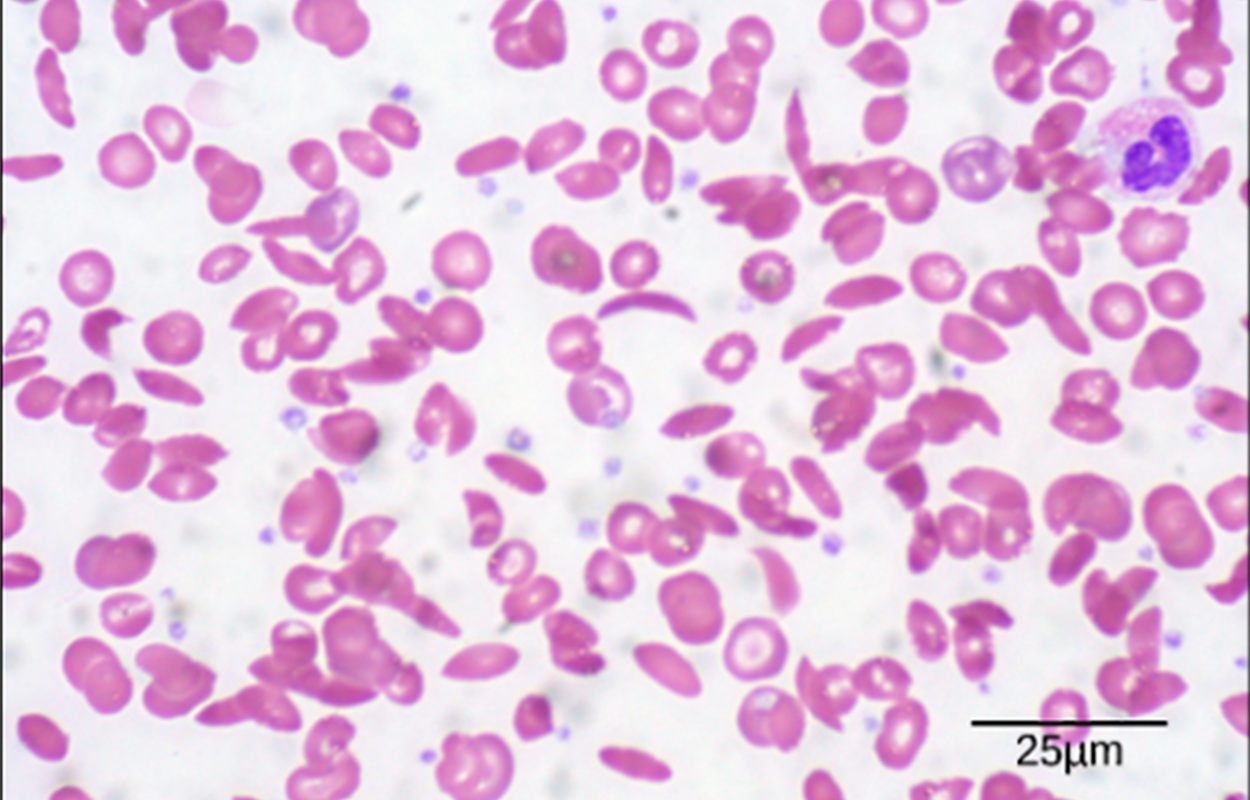

Because of this change of one amino acid in the chain, hemoglobin molecules form long fibers that distort the biconcave, or disc-shaped, red blood cells and assume a crescent or “sickle” shape, which clogs arteries (Figure 6). This can lead to myriad serious health problems such as breathlessness, dizziness, headaches, and abdominal pain for those affected by this disease.

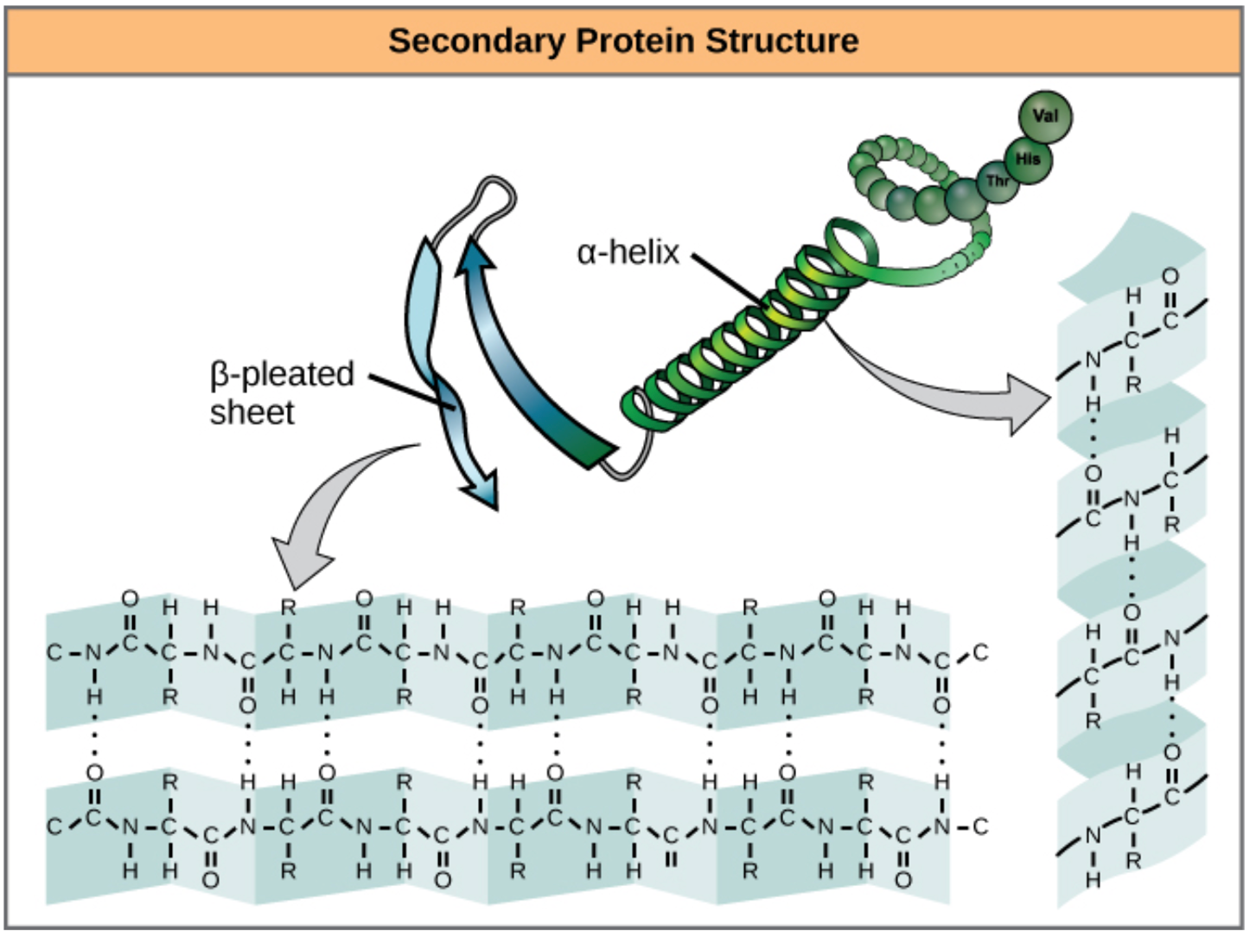

The local folding of the polypeptide in some regions gives rise to the secondary structure of protein. The most common are the α-helix and β-pleated sheet structures (Figure 7). Both structures are the α-helix structure—the helix held in shape by hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonds form between the oxygen atom in the carbonyl group in one amino acid and another amino acid that is four amino acids farther along the chain.

Every helical turn in an alpha helix has 3.6 amino acid residues. The R groups (the variant groups) of the polypeptide protrude out from the α-helix chain. In the β-pleated sheet, the “pleats” are formed by hydrogen bonding between atoms on the backbone of the polypeptide chain. The R groups are attached to the carbons and extend above and below the folds of the pleat. The pleated segments align parallel or antiparallel to each other, and hydrogen bonds form between the partially positive nitrogen atom in the amino group and the partially negative oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of the peptide backbone. The α-helix and β-pleated sheet structures are found in most globular and fibrous proteins and they play an important structural role.

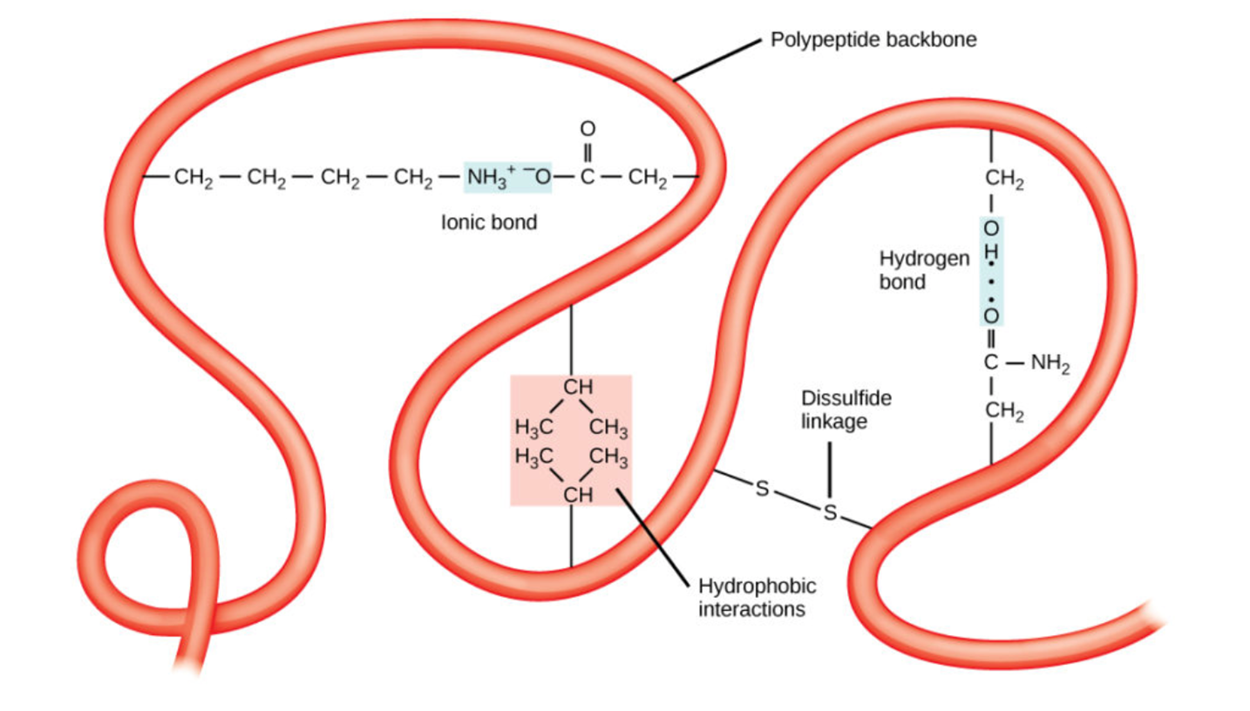

The unique three-dimensional structure of a polypeptide is the tertiary structure of protein (Figure 8). This structure is in part due to chemical interactions at work on the polypeptide chain. Primarily, the interactions among R groups creates the complex three-dimensional tertiary structure of a protein. The nature of the R groups found in the amino acids involved can counteract the formation of the hydrogen bonds described for standard secondary structures. For example, R groups with like charges are repelled by each other, and those with unlike charges are attracted to each other (ionic bonds). When protein folding takes place, the hydrophobic R groups of nonpolar amino acids lay in the interior of the protein, whereas the hydrophilic R groups lay on the outside. The former types of interactions are also known as hydrophobic interactions. Interaction between cysteine side chains forms disulfide linkages in the presence of oxygen, the only covalent bond forming during protein folding.

In nature, some proteins are formed from several polypeptides, also known as subunits, and the interaction of these subunits forms the quaternary structure. Weak interactions between the subunits help to stabilize the overall structure.

EXAMPLE

Insulin (a globular protein) has a combination of hydrogen bonds and disulfide bonds that cause it to be mostly clumped into a ball shape. Insulin starts out as a single polypeptide and loses some internal sequences in the presence of post-translational modification after the formation of the disulfide linkages that hold the remaining chains together. Silk (a fibrous protein), however, has a β-pleated sheet structure that is the result of hydrogen bonding between different chains.The four levels of protein structure (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary) are illustrated in the following image.

Each protein has its own unique sequence and shape that are held together by chemical interactions. If the protein is subject to changes in temperature, pH, or exposure to chemicals, the protein structure may change, losing its shape without losing its primary sequence in what is known as denaturation. Denaturation is often reversible because the primary structure of the polypeptide is conserved in the process if the denaturing agent is removed, allowing the protein to resume its function.

Protein folding is critical to its function. It was originally thought that the proteins themselves were responsible for the folding process. Only recently was it found that often they receive assistance in the folding process from protein helpers known as chaperones (or chaperonins) that associate with the target protein during the folding process. They act by preventing aggregation of polypeptides that make up the complete protein structure, and they disassociate from the protein once the target protein is folded.

The primary types and functions of proteins are listed in the table below.

| Protein Types and Functions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Examples | Functions |

| Digestive Enzymes | Amylase, lipase, pepsin, trypsin | Help in digestion of food by catabolizing nutrients into monomeric units |

| Transport | Hemoglobin, albumin | Carry substances in the blood or lymph throughout the body |

| Structural | Actin, tubulin, keratin | Construct different structures, like the cytoskeleton |

| Hormones | Insulin, thyroxine | Coordinate the activity of different body systems |

| Defense | Immunoglobulins | Protect the body from foreign pathogens |

| Contractile | Actin, myosin | Effect muscle contraction |

| Storage | Legume storage proteins, egg white (albumin) | Provide nourishment in early development of the embryo and the seedling |

Two special and common types of proteins are enzymes and hormones. Enzymes, which are produced by living cells, are catalysts in biochemical reactions (like digestion) and are usually complex or conjugated proteins. Each enzyme is specific for the substrate (a reactant that binds to an enzyme) it acts on. The enzyme may help in breakdown, rearrangement, or synthesis reactions. Enzymes that break down their substrates are called catabolic enzymes, enzymes that build more complex molecules from their substrates are called anabolic enzymes, and enzymes that affect the rate of reaction are called catalytic enzymes. It should be noted that all enzymes increase the rate of reaction and, therefore, are considered to be organic catalysts. An example of an enzyme is salivary amylase, which hydrolyzes its substrate amylose, a component of starch.

Hormones are chemical-signaling molecules, usually small proteins or steroids, secreted by endocrine cells that act to control or regulate specific physiological processes, including growth, development, metabolism, and reproduction. For example, insulin is a protein hormone that helps to regulate the blood glucose level.

Proteins have different shapes and molecular weights; some proteins are globular in shape whereas others are fibrous in nature.

EXAMPLE

Hemoglobin is a globular protein, but collagen, found in our skin, is a fibrous protein. Protein shape is critical to its function, and this shape is maintained by many different types of chemical bonds. Changes in temperature, pH, and exposure to chemicals may lead to permanent changes in the shape of the protein, leading to loss of function, known as denaturation. All proteins are made up of different arrangements of the same 20 types of amino acids.Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING’S “NUTRITION FLEXBOOK”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-nutrition/. LICENSE: creative commons attribution 4.0 international.