Table of Contents |

The best practice for finding sources is to begin with more than you need. If an assignment suggests five to seven sources, get a list of 10–15 to begin with, so you can then select the best for your argument. We will revisit this more in the next challenge.

But how can you get better at sorting truth from fiction—and everything in between? Applying your attention to the things that matter? Amplifying better treatments of issues, and avoiding clickbait? A solution is to follow these four steps when looking at a source, which are intended to be effective and not very time consuming.

The four steps are known as SIFT, which stands for:

The first move is the simplest: When you first hit a page or post and start to read it: Stop. Ask yourself whether you know the website or source of the information, and what the reputation of both the claim and the website is. If you don’t have that information, use the other moves to get a sense of what you’re looking at.

The idea here is that you want to know what you’re reading before you read it. Now, you don’t have to do a prize-winning investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics by a Nobel prize-winning economist, you should know that before you read it. Conversely, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption that was put out by the dairy industry, you want to know that as well.

Knowing the expertise and agenda of the source is crucial to your interpretation of what they say. Taking 60 seconds to figure out where media is from before reading will help you decide if it is worth your time, and if it is, help you to better understand its significance and trustworthiness.

Most documents include their date of publication. Pay attention to the date a source was created and reflect on what might have happened since then. Information may be outdated and useless. On the other hand, it may still be highly useful—and continuing usefulness is the reason many old texts remain in circulation. Once you locate the source’s date, you can decide whether it will be relevant for your purpose.

Sometimes you don’t care about the particular article or video that reaches you. You care about the claim the article is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement.

In this case, your best strategy may be to ignore the source that reached you and look for trusted reporting or analysis on the claim. If you get an article that says koalas have just been declared extinct, from the Save the Koalas Foundation, your best bet might not be to investigate the source, but to go out and find the best source you can on this topic, or, just as importantly, to scan multiple sources and see what the expert consensus seems to be. In these cases, you can find other coverage that better suits your needs—more trusted, more in-depth, or maybe just more varied.

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on research findings, but you’re not sure if the cited research paper really said that. In these cases, trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source so you can see it in its original context and get a sense if the version you saw was accurately presented.

There’s a theme that runs through all of these moves: They are about reconstructing the necessary context to read, view, or listen to digital content effectively. So, what is context?

Remember that not all sources are created equally. You likely know already that you must vet sources—especially those you find on the internet—for legitimacy, validity, and the presence of bias. A broad online search will yield thousands of sources, which no one could be expected to read through.

IN CONTEXT

Wikipedia

Wikipedia is open to user editing. This accessibility means the site’s authority cannot be established and, therefore, the source cannot effectively support or refute a claim you are attempting to make, though you can use this resource to point you to reliable sources, or to help you get started understanding your topic.

Consider a situation where you need to find information on young adult and teen use of vapes. Wikipedia will summarize what is known and, more importantly, will source each claim, as follows:

Select image to open in an enlarged view.

Each footnote leads to a source that the community has deemed reliable. If you are researching a complex question, starting with the resources and summaries provided by Wikipedia can give you a substantial start on understanding an issue.

When searching for popular, credible resources online for academic essay writing, students should focus on identifying sources that are trustworthy, current, and relevant to their topic. Credible popular sources—such as reputable news outlets, government websites, and professional organizations—offer well-researched information that can help support background knowledge or illustrate public perspectives. Follow the SIFT strategy.

Remember that Google is a massive online search engine that aims to organize the world's information and make it accessible to users by providing a platform to search for relevant and reliable results across the web, drawing from a vast array of sources, including websites, documents, images, and videos, and presenting them based on complex algorithms that prioritize relevance to the user's search query—essentially acting as a gateway to the internet's information pool.

The exact details of Google's algorithm are not publicly known, making it difficult for users to understand why certain results appear higher than others. Websites can manipulate their ranking by employing techniques like keyword stuffing or link farming, which can push irrelevant content to the top of search results. Prominent ad placements within search results can sometimes obscure organic, high-quality information. Due to the vast amount of content online, Google can sometimes surface inaccurate or misleading information, especially when queries are ambiguous. The personalization feature can create a "filter bubble" where users only see information aligned with their existing beliefs, potentially limiting exposure to diverse perspectives.

Another incredible resource to help you get started: local and college librarians! For help locating resources, you will find that librarians are extremely knowledgeable and may help you uncover sources you would never have found on your own. You will not know unless you utilize the valuable skills available to you, so be sure to find out how to get in touch with a research librarian for support! Many college and community libraries have online research guides that point you to the best databases for the specific discipline and, perhaps, the specific course. Librarians are eager to help you succeed with your research—it’s their job and they love it!—so don’t be shy about asking.

Academic databases are searchable collections of scholarly content, such as journal articles, books, and conference proceedings. They can be subject-specific or multidisciplinary. Academic research databases are essential sources of information for researchers, academics, and scholars. These databases are academic search engines that help academics stay updated on the latest developments in their field. Scholarly databases support their own work with credible sources and contribute to the overall progress of knowledge and literature in different disciplines. Let’s understand more about academic databases.

Academic databases help researchers and students access pertinent information for their papers or studies. Many times, these articles are accessible online, making academic databases a convenient and efficient tool for retrieving essential academic materials. Some popular academic research databases include Scopus for various research, JSTOR for humanities and social sciences, PubMed for medical research, and IEEE Xplore for engineering and technology.

EXAMPLE

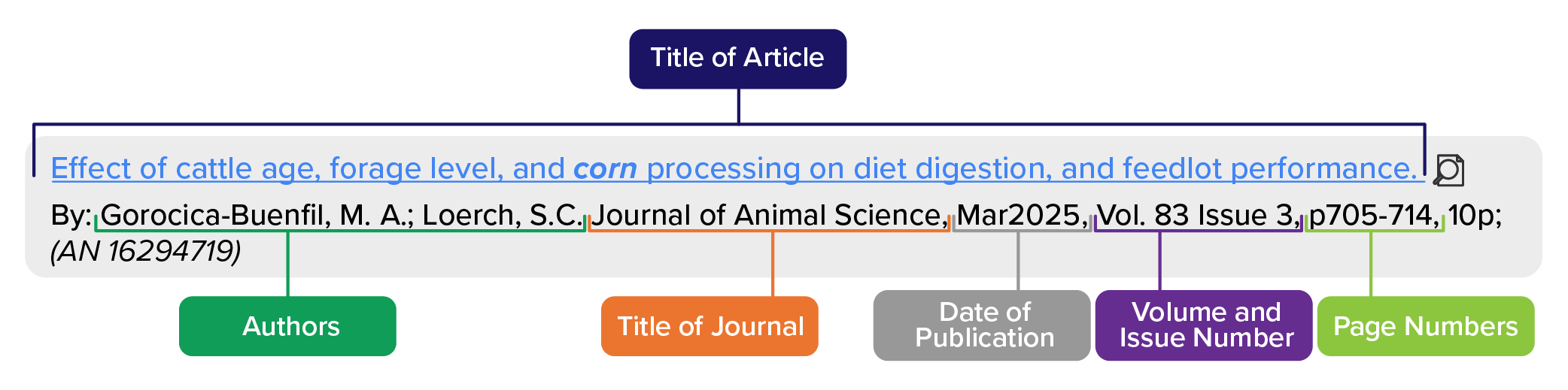

Take a look at this sample article from an academic database:

Another option is scholar.google.com. It looks like a regular Google search, and it aims to include the vast majority of scholarly resources available. Here are some tips for using Google Scholar effectively:

You can save yourself time and frustration later if you keep a good log of your research, writing down each source and location or copying and pasting the info into a word processing document or notes app. This will be helpful as you dive back into selected sources to create a bibliography, write your paper, and add the reference to the references page.

For this last reason, you should get in the habit of recording the info in the right format -- in this class, it is APA. A typical online source looks like this:

You don't need to worry about learning APA formatting yet, just keeping a good record of your research. But many academic articles or the databases that host them will have a "Cite" button (it might like a quote mark) that allows you to copy the correctly formatted reference in its entirety. All you have to do is paste this into a document, and you have all the information you need to return to each source as you write your paper. Better yet, your "References" page is already (almost) done!

REFERENCES

Caulfield, M. (2019). SIFT: The four moves. Hapgood. hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/

Caulfield, M. (2021). Wikipedia. In Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers. Pressbooks. pressbooks.pub/webliteracy/chapter/wikipedia/

Researcher.Life. (n.d.). Academic Databases: A Guide for Researchers. researcher.life/blog/article/academic-databases-a-guide-for-researchers/

Troyka, L. Q., & Hesse, D. (2016). Simon and Schuster Handbook for Writers (11th ed.).