Table of Contents |

Grief is the psychological, physical, and emotional experience and reaction to loss. Grief reactions vary depending on whether a loss was anticipated or unexpected, whether or not it occurred suddenly or after a long illness, and whether or not the survivor feels responsible for the death. Survivor guilt (or survivor’s guilt; also called survivor syndrome or survivor’s syndrome) is a mental condition that occurs when a person perceives themselves to have done wrong by surviving a traumatic event when others did not. It may be found among survivors of combat, natural disasters, and epidemics, and among the friends and family of those who have died by suicide. These survivors may torment themselves with endless “what ifs” in order to make sense of the loss and reduce feelings of guilt.

Family members may also hold one another responsible for the loss. The same may be true for any sudden or unexpected death, making conflict an added dimension to grief. Much of this laying of responsibility is an effort to think that we have some control over these losses, the assumption being that if we do not repeat the same mistakes, we can control what happens in our life. While grief describes the response to loss, bereavement describes the state of being following the death of someone.

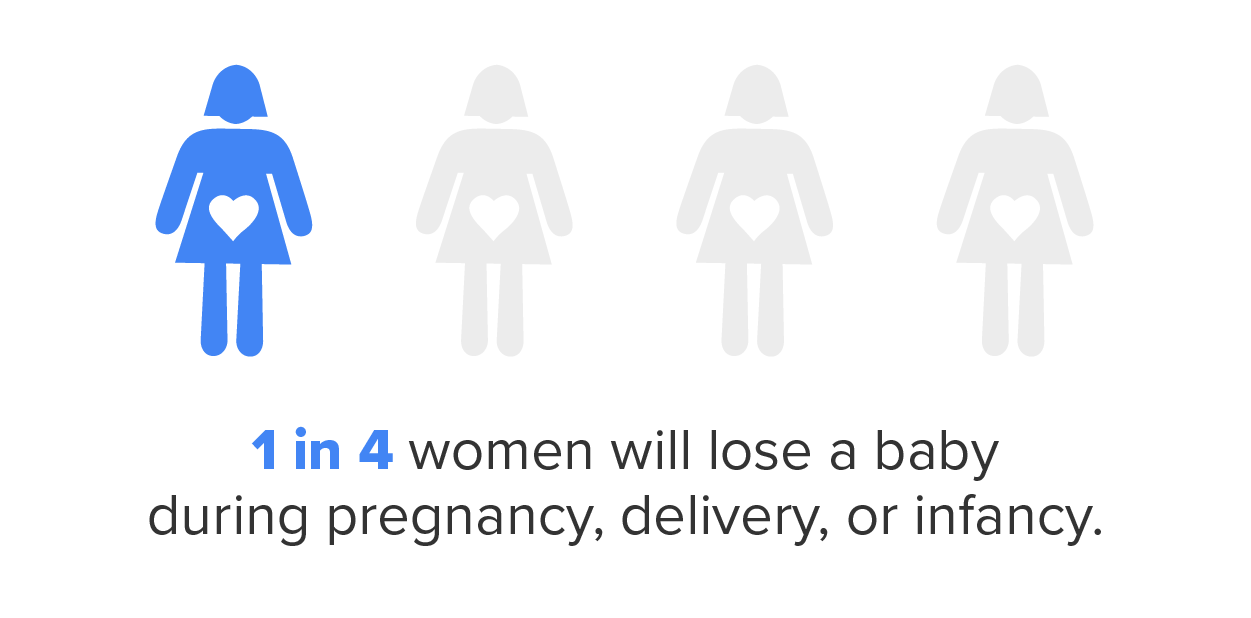

Death of a child can take many forms. This loss can include death during infancy due to miscarriage, stillbirth, neonatal death, SIDS, or the death of an older child. Parents find the grief unbearably devastating, and it tends to hold greater risk factors than any other loss. This loss also bears a lifelong process; one does not “get over” the death but instead must determine a new normal and live with the loss. Intervention and comforting support can make all the difference to the survival of a parent in this type of grief, but the risk factors are great and may include family breakup or suicide. Parents who have had a child die before their first birthday are twice as likely to die in the first 15 years following their child’s death, compared to parents who have not lost a child (Gann, 2011). Feelings of guilt, whether legitimate or not, are pervasive, and the dependent nature of the relationship disposes parents to a variety of problems as they seek to cope with this great loss. It’s estimated that 20% of parents will experience miscarriage (March of Dimes, 2023), and by age 60, about 9% of parents have experienced the death of a child (Evermore, 2020). Parents who suffer miscarriage or a regretful or coerced abortion may experience resentment towards others who experience successful pregnancies.

Suicide rates are growing worldwide and over the last 30 years, there has been international research trying to curb this phenomenon and gather knowledge about who is at risk. When a parent loses their child through suicide, it is traumatic, sudden, and affects all loved ones impacted by this child. Suicide leaves many unanswered questions and leaves most parents feeling hurt, angry, and deeply saddened by such a loss. Parents may feel they can’t openly discuss their grief and feel their emotions because of how their child died and how the people around them may perceive the situation. Parents, family members, and service providers have all confirmed the unique nature of suicide-related bereavement following the loss of a child. They report a wall of silence that goes up around them and impacts how people interact with them.

The death of a spouse is usually a particularly powerful loss. A spouse often becomes part of the other in a unique way, and many widows and widowers describe losing “half” of themselves. The days, months, and years after the loss of a spouse will never be the same, and learning to live without them may be harder than one would expect. The grief experience is unique to each person. Sharing and building a life with another human being then learning to live singularly can be an adjustment that is more complex than a person could ever expect. Depression and loneliness are very common. After a long marriage, it may be very difficult for assimilation to begin anew. A marriage relationship was often a profound one for the survivor.

IN CONTEXT

Most couples have a division of tasks or labor. For example, one spouse mows the yard, while the other pays the bills. When one spouse dies, in addition to dealing with great grief and life changes, there are now added responsibilities for the bereaved as they must now take on the tasks of their spouse. The living spouse must also be in charge of planning and financing a funeral, changes in insurance, bank accounts, claiming life insurance, and securing childcare; these are just some of the issues that can be intimidating to someone who is grieving. Social isolation may also become imminent, as many groups composed of couples find it difficult to adjust to the new identity of the bereaved, and the bereaved themselves have great challenges in reconnecting with others.

For a child, the death of a parent, without support to manage the effects of the grief, may result in long-term psychological harm (Ellis & Lloyd-Williams, 2008). This is more likely if the adult caregivers are struggling with their own grief and are psychologically unavailable to the child. There is a critical role for the surviving parent or caregiver in helping the children adapt to a parent’s death. Studies have shown that losing a parent at a young age did not just lead to negative outcomes; there are some positive effects. Some children were more mature, had better coping skills, and had better communication than children who did not experience the loss of a parent. Adolescents valued other people more than those who have not experienced such a close loss.

When an adult child loses a parent in later adulthood, it is considered to be a normative life course event. This allows the adult children to feel a permitted level of grief. However, research shows that the death of a parent in an adult’s midlife is not a normative event by any measure but is a major life transition causing an evaluation of one’s own life or mortality. Others may shut out friends and family in processing the loss of someone with whom they have had the longest relationship.

The loss of a sibling can be a devastating life event. Despite this, sibling grief is often the most disenfranchised or overlooked of the four main forms of grief, especially with regard to adult siblings. Grieving siblings are often referred to as the forgotten mourners who are made to feel as if their grief is not as severe as their parent's grief. However, the sibling relationship tends to be the longest significant relationship of the lifespan, and siblings who have been part of each other’s lives since birth, such as twins, help form and sustain each other’s identities; with the death of one sibling comes the loss of that part of the survivor’s identity because their identity is based on having that sibling there.

When a parent or caregiver dies or leaves, children may have symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, but they are less severe than in children with major depression. The loss of a parent, grandparent, or sibling can be very troubling in childhood, but even in childhood, there are age differences in relation to the loss. A very young child, under 1 or 2 years old, may be found to have no reaction if a caregiver dies, but other children may be greatly affected by the loss.

At a time when trust and dependency are formed, separation can cause problems in well-being; this is especially true if the loss is around critical periods such as 8–12 months when attachment is at its height in developmental importance, and even a brief separation from a caregiver can cause distress.

Even as a child grows older, death is still difficult to fathom, and this affects how a child responds. For example, younger children see death more as separation and may believe death is curable or temporary. Reactions can manifest themselves in “acting out” behaviors: a return to earlier behaviors such as sucking thumbs, clinging to a toy, or angry behavior. Though they do not have the maturity to mourn as an adult, they feel the same intensity. As children enter pre-teen and teen years, there is a more mature understanding.

IN CONTEXT

Children can experience grief as a result of losses due to causes other than death. For example, children who have been physically, psychologically, or sexually abused often grieve over the damage to or the loss of their ability to trust. Since such children usually have no support or acknowledgment from any source outside the family unit, this is likely to be experienced as disenfranchised grief, or the experiences of those who have to hide the circumstances of their loss or whose grief goes unrecognized by others. Relocations can also cause children significant grief, particularly if they are combined with other difficult circumstances such as neglectful or abusive parental behaviors, divorce, the loss of friendships, and more.

Children may experience the death of a friend or a classmate through illness, accidents, suicide, or violence. Initial support involves reassuring children that their emotional and physical feelings are normal and additional help can be provided when needed. Schools are advised to plan for these possibilities in advance and often have a plan in place if this were to occur.

People may experience grief in various ways, but several theories, such as Kübler-Ross’s stages of loss theory, attempt to explain and understand the way people deal with grief. Kübler-Ross’s famous theory describes five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Kübler-Ross (1965) described these five stages based on her work and interviews with terminally ill patients. These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once, nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity; it’s more of a fluid experience. The process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life.

Since Kübler-Ross presented stages of loss, several other models have been developed. These subsequent models build on that of Kübler-Ross, offering expanded views of how individuals may process loss and grief. One such model was presented by William Worden (1991). The Tasks of Grief explained the process of grief through a set of four different tasks that the individual must complete in order to resolve the grief. These tasks include accepting that the loss has occurred, working through and experiencing the pain associated with grief, adjusting to the changes that the loss created in the environment, and moving past the loss on an emotional level.

In 1970, Bowlby and Parkes (1998) identified a four-stage model of mourning that included shock, yearning, despair, and recovery. Although comprised of somewhat different stages than those of Kübler-Ross’s model, Bowlby and Parkes’s stages still reflected an ongoing process that the individual goes through, each of which was characterized by different thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Throughout this process, the individual gradually moves closer to accepting the situation and being able to continue with their daily life to the greatest extent possible.

Anticipatory grief occurs when a death is expected and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss. Anticipatory grief can include the same denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance experienced in loss that one might experience after a death, although a person may then go through the stages of loss again after the death. A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over or the exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is over.

Complicated grief involves a distinct set of maladaptive or self-defeating thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that occur as a negative response to a loss (Boelen & Prigerson, 2007). From a cognitive and emotional perspective, these individuals tend to experience extreme bitterness over the loss, intense preoccupation with the deceased, and a need to feel connected to the deceased. These feelings often lead the grieving individual to engage in problematic behaviors that further prevent positive coping and delay the return to normalcy. They may spend excessive amounts of time visiting the deceased person’s grave, talking to the deceased person, or trying to connect with the deceased person on a spiritual level, often foregoing other responsibilities or tasks to do so. The extreme nature of these thoughts, emotions, and behaviors separates this type of grief from the normal grieving process.

In March 2022, prolonged grief disorder (PGD) was added as a mental disorder in the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022). It is characterized by a distinct set of symptoms following the death of a family member or close friend. People with PGD are preoccupied with grief and feelings of loss to the point of clinically significant distress and impairment, which can manifest in a variety of symptoms including depression, emotional pain, emotional numbness, loneliness, identity disturbance, and difficulty in managing interpersonal relationships. Difficulty accepting the loss is also common, which can present as rumination about the death, a strong desire for reunion with the departed, or disbelief that the death occurred. PGD is estimated to be experienced by about 10% of bereaved survivors, although rates vary substantially depending on populations sampled and definitions used (Lundorff et al., 2017).

Along with the bereavement of the individual occurring at least 1 year ago (or 6 months in children and adolescents), there must be evidence of one of two “grief responses” occurring at least daily for the past month. These grief responses include intense yearning/longing for the deceased person and preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person (in children and adolescents, preoccupation may focus on the circumstances of the death).

The duration and severity of the distress and impairment in PGD must be clinically significant, and not better explainable by social, cultural, or religious norms, or another mental disorder. PGD can be distinguished from depressive disorders with distress appearing specifically about the bereaved as opposed to a generally low mood. According to Holly Prigerson, an editor on the trauma and stressor-related disorder section of the DSM-5-TR, “intense, persistent yearning for the deceased person is specifically a characteristic symptom of prolonged grief but is not a symptom of major depressive disorder (or any other DSM disorder).”

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING'S LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Gibbons, J. A., Lee, S. A., Fehr, A. M., Wilson, K. J., & Marshall, T. R. (2018). Grief and avoidant death attitudes combine to predict the fading affect bias. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1736), 1-19.

Gann, C. (2011). Grieving parents face higher risk of early death, study says. ABC News Medical Unit. abcnews.go.com/Health/grieving-parents-risk-early-death-study/story?id=14467734

March of Dimes. (2023). Miscarriage. www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/miscarriage-loss-grief/miscarriage#:~:text=For%20women%20who%20know%20they,12th%20week%20of%20pregnancy.

Evermore. (2020). Bereavement facts & figures: September 2020. evermore.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Evermore-Bereavement-Facts-and-Figures-2020.pdf

Ellis, J., & Lloyd-Williams, M. (2008). Perspectives on the impact of early parent loss in adulthood in the UK: Narratives provide the way forward. European Journal of Cancer Care, 17(4), 317–318. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00963.x. PMID 18638179

Worden, J. W. (1991). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O'Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 138-149. doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Boelen, P. A., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci., 257, 444–452.

Parkes, C. M. (1998). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life (3rd ed.). International Universities Press, Inc.