Table of Contents |

The time between a child’s 2nd and 6th birthdays is full of new social experiences. At the beginning of this stage, a child selfishly engages in the world—the goal is to please the self. As the child gets older, they realize that relationships build on give-and-take. They start to learn to empathize with others. They learn to make friends. Learning to navigate the social sphere is difficult, but children do it readily.

Children internalize parental rules and begin to feel guilt when they break rules. Their self-concept is also developing at this stage and is heavily influenced by interactions with their parents and the culture in which they live. Self-esteem also becomes more developed, as children in this stage usually evaluate themselves very positively and have unrealistic views of their abilities. Young children’s perspective on their skills is related to their cognitive development and secure attachment with caregivers.

IN CONTEXT

While the child is learning about their place in various relationships, they are also developing an understanding of emotions. A 2-year-old does not have a good grasp on their emotions, but by the time a child is 6, they understand their emotions better. They also understand how to control their emotions (also known as self-regulation)—even to the point that they may put on a different emotion than they are actually feeling. Further, by the time a child is 6 years old, they understand that other people have emotions and that all of the emotions involved in a situation (theirs and other people’s) should be considered. That said, although the 6-year-old understands these things, they are not always good at putting the knowledge into action. We will examine some of these issues in this lesson.

The development of play is an important milestone in early childhood. Play holds a crucial role in providing a safe, caring, protective, confidential, and containing space where children can recreate themselves and their experiences through an exploratory process (Winnicott, 1942; Erikson, 1963). During this stage, pretend play is a great way for children to express their thoughts, emotions, fears, and anxieties.

One type of pretend play is sociodramatic play, where children imitate adults and take on adult roles and activities, like playing house or doctor. Vygotsky saw sociodramatic play as fuel for cognitive, social, and emotional development, and research confirmed it, showing sociodramatic play predicted better self-regulation in 3- and 4-year-olds (Elias & Berk, 2002).

Another important type of pretend play is rough and tumble play, or play fighting, wrestling, and chasing. Commonly seen in rats, monkeys, and other mammals, rough and tumble play is believed to be an evolutionary adaptation that helps build the social brain (Pellis & Pellis, 2007). It’s more frequent and rougher among boys and is associated with social competence in humans. Rough and tumble play is different from real fighting, as the participants are often laughing and taking care not to harm each other. It helps children learn restraint and impulse control.

Early childhood play can be understood by observing the elements of fantasy, organization, and comfort. Fantasy, the process of make-believe, is an essential behavior the child engages in during pretend play; organization helps the child to structure pretend play into a story and to utilize cause-and-effect thinking; and comfort is used to assess the ease and pleasure in the engagement in play (Salcuni, Di Riso, Mabilia, & Lis, 2017).

As children progress through the stage of early childhood, they also progress through several stages of nonsocial and social play. Stages of play is a theory and classification of participation in play developed by Mildred Parten Newhall in 1929. Newhall observed American children at free play and recognized six different types of play:

While Erik Erikson was very influenced by Freud, he believed that the relationships that people have, not psychosexual stages, are what influence personality development. At the beginning of early childhood, the child is still in the autonomy versus shame and doubt stage (stage 2).

By age three, however, the child begins stage 3, which is initiative versus guilt. The trust and autonomy of previous stages develop into a desire to take initiative or to think of ideas and initiate action. Children are curious at this age and start to ask questions so that they can learn about the world. Parents should try to answer those questions without making the child feel like a burden or implying that the child’s question is not worth asking.

IN CONTEXT

These children are also beginning to use their imagination (remember what we learned when we discussed Piaget!). Children may want to build a fort with cushions from the living room couch, open a lemonade stand in the driveway, or make a zoo with their stuffed animals and issue tickets to those who want to come. Another way that children may express autonomy is in wanting to get themselves ready for bed without any assistance. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being overly critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pale in comparison to the smiling face of a 5-year-old emerging from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas!

That said, it is important that the parent does their best to kindly guide the child to the right actions. Remember that according to Freud and Kohlberg, children are developing a sense of morality during this time. Erikson agrees. If the child does leave those soggy washrags in the sink, then have the child help clean them up. It is possible that the child will not be happy with helping to clean, and the child may even become aggressive or angry, but it is important to remember that the child is still learning how to navigate their world. They are trying to build a sense of autonomy, and they may not react well when they are asked to do something that they had not planned. Parents should be aware of this, and try to be understanding, but also firm.

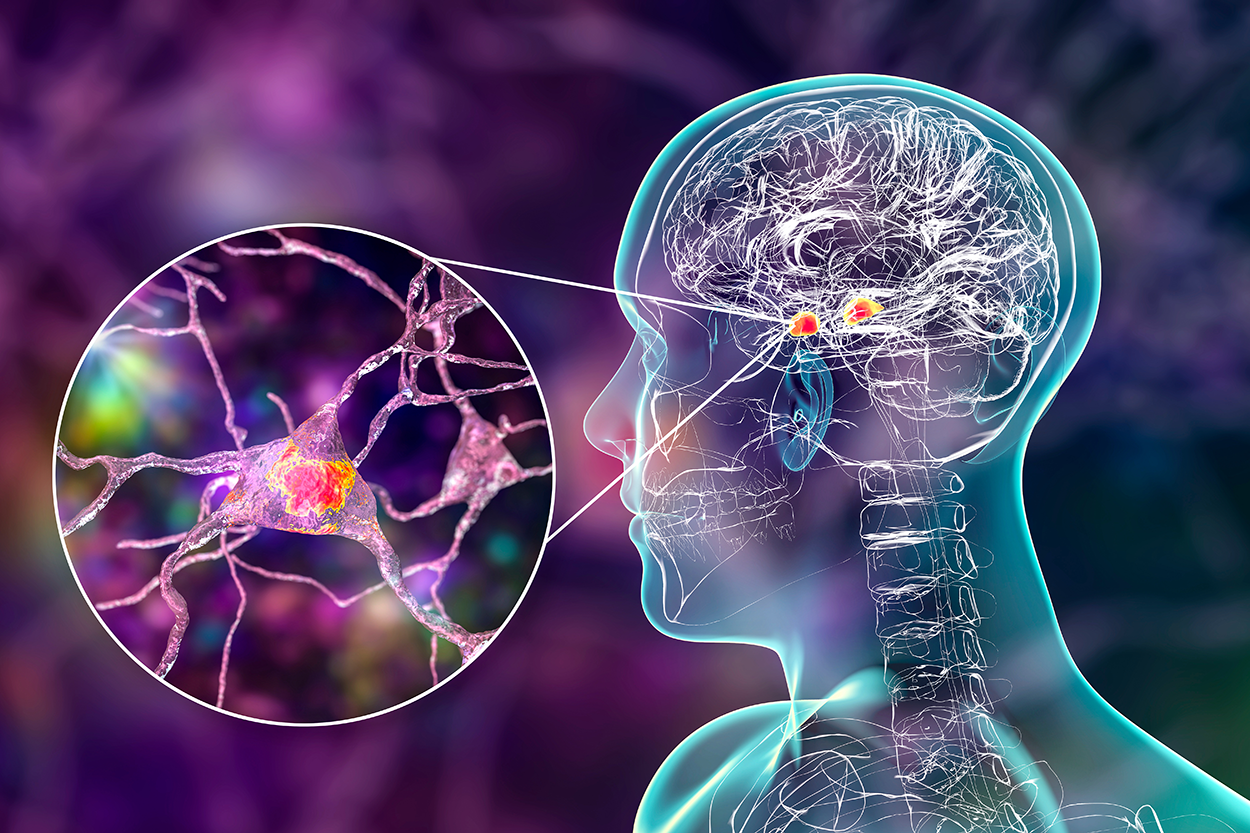

One of the most important milestones in early childhood is the development of emotional regulation. As the prefrontal cortex (PFC) matures and pathways between the PFC and the amygdala (emotion center of the brain) become myelinated, children improve in their ability to control when and how their emotions are expressed (Martin & Ochsner, 2016). The PFC is one of the last brain regions to fully develop, and as such, children need explicit coaching and practice with emotional regulation at this age.

In young children, we often hear the term emotional self-regulation, which is the ability of the child to manage their own emotions and behaviors. The first step in learning how to self-regulate is to build emotional intelligence, or the ability to identify, label, express, and manage one’s emotions.

Bridges and Grolnick (1995) highlight two important processes of emotional self-regulation:

IN CONTEXT

The National Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP) released a brief on socioemotional development during the early childhood years (Cooper, Masi, & Vick, 2009). The aim of this brief was to promote overall health, well-being, and economic security for low-income families and children in the United States. In the context of young children’s social-emotional needs, between 9.5% and 14.2% of children (birth to 5 years old) display socioemotional issues that further impact their school, overall functioning, and developmental outcomes (Brauner & Stephens, 2006). Moreover, an estimated 9% of children who receive mental health services in the United States are 6 years old or younger (Warner & Pottick, 2006). It is therefore imperative to understand and address how socioenvironmental factors can impact emotional and behavioral outcomes during the early years so that early intervention can take place to promote emotional well-being in children and offset any developmental delays in this area.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING'S LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Winnicott, D. W. 1942. “Why Children Play.” In The Child, the Family and the Outside World, 143–146. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Elias, C. L., & Berk, L. E. (2002). Self-regulation in young children: Is there a role for sociodramatic play?. Early childhood research quarterly, 17(2), 216-238.

Pellis, S. M., & Pellis, V. C. (2007). Rough-and-tumble play and the development of the social brain. Current directions in psychological science, 16(2), 95-98.

Salcuni, S., Di Riso, D., Mabilia, D., & Lis, A. (2017). Psychotherapy with a 3-year-old child: the role of play in the unfolding process. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 2021.

Warner, L. A., & Pottick, K. J. (2006). Functional impairment among preschoolers using mental health services. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(5), 473-486.

Brauner, C. B., & Stephens, C. B. (2006). Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: Challenges and recommendations. Public health reports, 121(3), 303-310.

Cooper, J. L., Masi, R., & Vick, J. (2009). Social-emotional development in early childhood: What every policymaker should know.

Bridges, L. J., & Grolnick, W. S. (1995). The development of emotional self-regulation in infancy and early childhood. Social development, 15, 185-211.

Martin, R. E., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The neuroscience of emotion regulation development: Implications for education. Current opinion in behavioral sciences, 10, 142-148.

Schleien, S. J., Rynders, J. E., Mustonen, T., & Fox, A. (1990). Effects of social play activities on the play behavior of children with autism. Journal of Leisure Research, 22(4), 317-328.

Mastrangelo, S. (2009). Play and the child with autism spectrum disorder: From possibilities to practice. International journal of play therapy, 18(1), 13-30.