Table of Contents |

Recall that skeletal muscle is a voluntary muscle tissue that is attached to bones or skin. This tissue combines with epithelial, connective, and nervous tissues to form the muscles of the muscular system, performing a range of functions.

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| Contract and cause movement | When activated, skeletal muscle tissue shortens, causing the bones (or skin) that it is attached to to move. |

| Contract and resist movement | The activation of certain skeletal muscles can stop movement instead of causing it. Small, constant adjustments of the skeletal muscles are needed to hold a body upright or balanced in any position, resisting gravity. Muscles also prevent excess movement of the bones and joints, maintaining skeletal stability and preventing skeletal structure damage or deformation. Joints can become misaligned or dislocated entirely by pulling on the associated bones; muscles work to keep joints stable. |

| Regulate body openings | Skeletal muscles are located throughout the body at the openings of internal tracts to control the movement of various substances. These muscles allow functions (such as swallowing, urination, and defecation) to be under voluntary control. |

| Protect internal organs | Skeletal muscles also protect internal organs (particularly abdominal and pelvic organs) by acting as an external barrier or shield to external trauma and by supporting the weight of the organs. |

| Generate heat | Skeletal muscles perform contractions that require energy. When ATP is broken down, heat is produced. This heat contributes to the maintenance of homeostasis. During exercise (sustained muscle movement), it can also be very noticeable, causing body temperature to rise. In cases of extreme cold, shivering produces random skeletal muscle contractions to generate heat. |

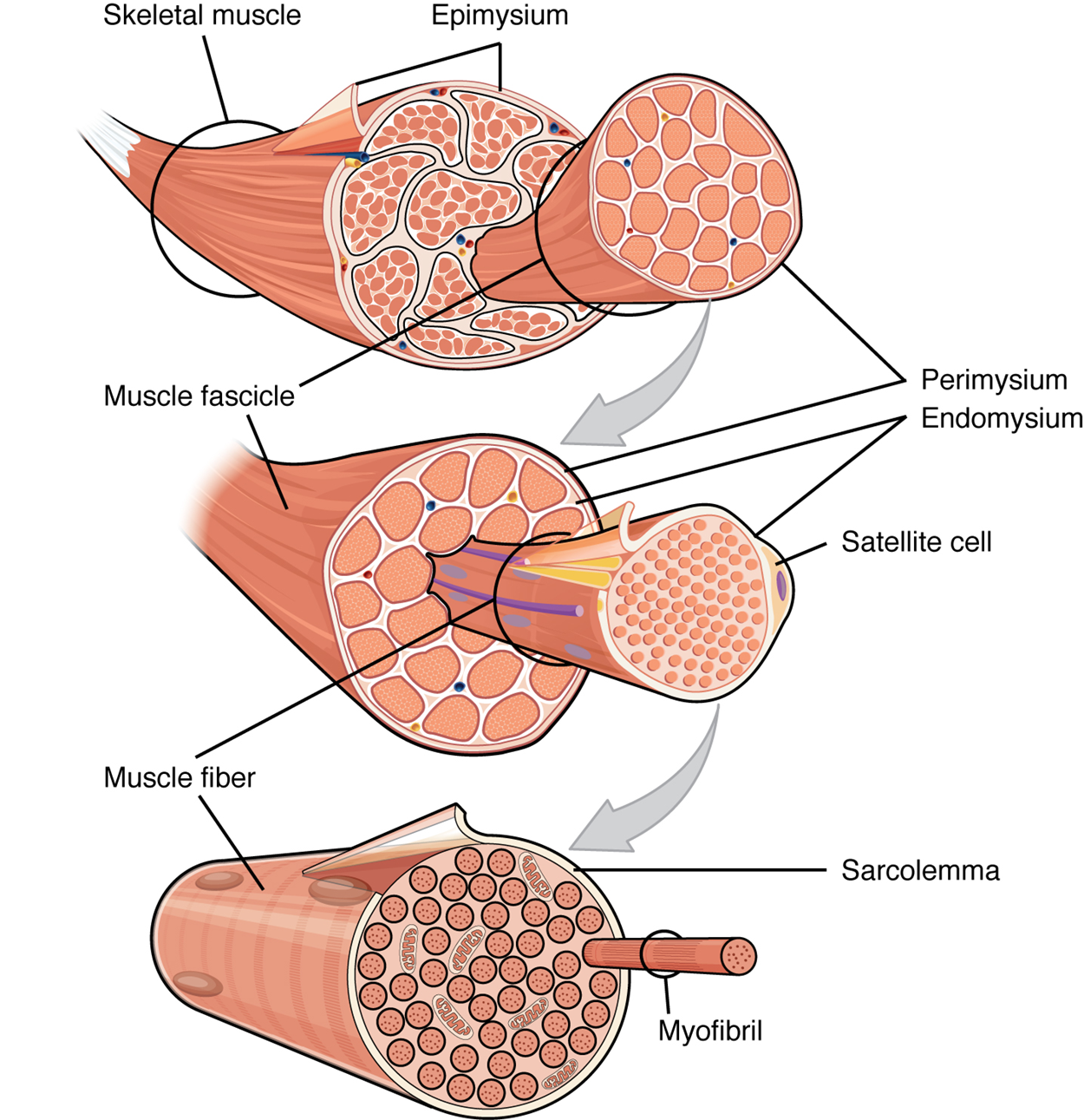

Each skeletal muscle is an organ that consists of various integrated tissues and structures. These tissues include blood vessels, nerve fibers, connective tissue, and skeletal muscle fibers, also known as skeletal muscle cells. Each skeletal muscle has three layers of connective tissue (called “mysia”) that enclose it, compartmentalize its muscle fibers, and provide structure to the muscle as a whole. Each muscle is wrapped in a sheath of dense, irregular connective tissue called the epimysium, which allows a muscle to contract and move powerfully while maintaining its structural integrity. The epimysium also separates muscle from other tissues and organs in the area, allowing the muscle to move independently.

Inside each skeletal muscle, several muscle fibers are organized into individual bundles, each called a muscle fascicle, by a middle layer of connective tissue called the perimysium. This fascicular organization is common in muscles of the limbs; it allows the nervous system to be selective in how much of a muscle it activates at one time. Inside each fascicle, each muscle fiber is encased in a thin connective tissue layer of collagen and reticular fibers called the endomysium. The endomysium contains extracellular fluid and nutrients to support the muscle fiber. These nutrients are supplied via blood to the muscle tissue.

The connective tissue wrappings of a skeletal muscle continue at each end of the muscle to form a tendon. Recall that a tendon is a cord-like dense regular connective tissue structure that attaches a skeletal muscle to a bone. The collagen in the three tissue layers (the mysia) intertwines with the collagen of a tendon. At the other end of the tendon, it fuses with the periosteum coating the bone. The tension created by contraction of the muscle fibers is then transferred through the mysia, to the tendon, and then to the periosteum to pull on the bone for movement of the skeleton. In other places, the mysia may fuse with a broad, tendon-like sheet called an aponeurosis. Muscles that attach to small single points of a bone do so using tendons (e.g., biceps brachii). Muscles that attach to broad or wide regions of a bone use an aponeurosis (e.g., frontalis). Some muscles use a tendon on one end and an aponeurosis at the other (e.g., latissimus dorsi, or “lats”).

Every skeletal muscle is also richly supplied by blood vessels for nourishment, oxygen delivery, and waste removal. In addition, every muscle fiber in a skeletal muscle is supplied by a neuron, which signals the fiber to contract. Unlike cardiac and smooth muscle, the only way to functionally contract a skeletal muscle is through signaling from the nervous system.

As you have learned, skeletal muscles interact with your skeleton in order to allow for voluntary movement. Skeletal muscles are the most common type of muscle in your body.

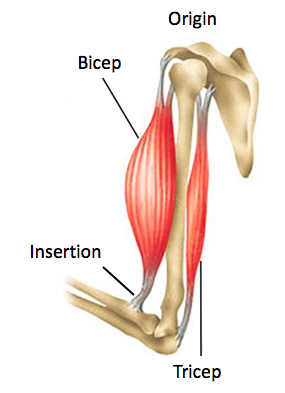

To look at how skeletal muscles work with the skeletal system, use the biceps and triceps found in our upper arm as an example:

Tendons are what connect muscle to bone or to other muscles. They work to stabilize joints and are made of dense connective tissue. Tendons are what actually connect our muscle to our bone at the origin and insertion.

The origin is the end of a muscle that attaches to a stable bone. If you use the diagram above as an example, the stable bone is the scapula, and the origin is where the bicep is attached. The insertion, then, is the movable end of the muscle that attaches to a bone.

Keep in mind that the biceps and triceps are an example of skeletal muscles working in pairs. They work antagonistically with (in opposition to) each other. Later on, you will look at this in more depth, but for now, it is important to note that some skeletal muscles work in groups this way.

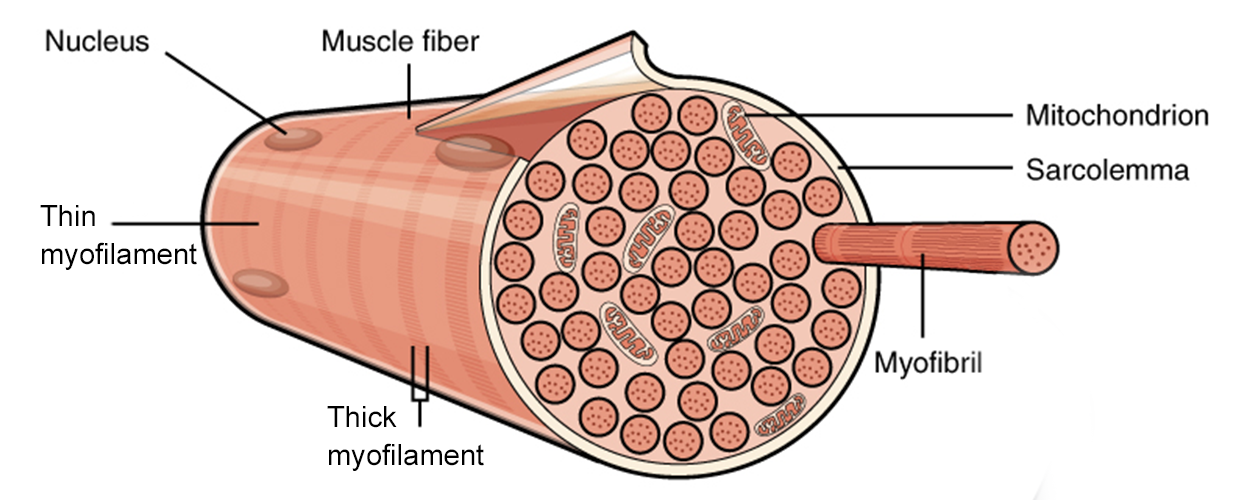

Much of the terminology associated with muscle fibers that you will learn throughout this and future lessons is rooted in two Greek root words; sarco and myo.

Skeletal muscle cells are long and cylindrical and can be quite large for human cells, with diameters up to 100 μm (micrometre or micrometer, also commonly known as a micron) and lengths up to 30 cm (11.8 in). During early development, embryonic stem cells called myoblasts, each with its own nucleus, fuse with up to hundreds of other myoblasts to form a single multinucleated skeletal muscle fiber. Multiple nuclei mean multiple copies of genes, permitting the production of large amounts of proteins and enzymes needed for muscle contraction.

Recall that most cells, including muscle fibers, contain multiple organelles and structures. The muscle fiber, however, has specific names for a few of the common structures. The plasma membrane of muscle fibers is called the sarcolemma, the cytoplasm is referred to as sarcoplasm, and the specialized smooth endoplasmic reticulum, which stores, releases, and retrieves calcium ions (Ca⁺⁺), is called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Each muscle fiber also contains hundreds to thousands of unique cylindrical organelles called myofibrils composed of myofilaments, or protein filaments.

Two criteria to consider when classifying the types of muscle fibers are how fast some fibers contract relative to others and how fibers produce ATP. Using these criteria, there are three main types of skeletal muscle fibers. Most skeletal muscles in a human contain all three types, although in varying proportions:

Fast skeletal muscles are also known as white skeletal muscle, and slow skeletal muscles are also known as red skeletal muscles.

Oxidative fibers contain many more mitochondria than the glycolytic fibers because aerobic metabolism, which uses oxygen (O₂) in the metabolic pathway, occurs in the mitochondria. The SO fibers possess a large number of mitochondria and are capable of contracting for longer periods because of the large amount of ATP they can produce, but they have a relatively small diameter and do not produce a large amount of tension. SO fibers are extensively supplied with blood capillaries to supply O₂ from the red blood cells in the bloodstream. The SO fibers also possess myoglobin, an O₂-carrying molecule similar to O₂-carrying hemoglobin in the red blood cells. The myoglobin stores some of the needed O₂ within the fibers themselves (and gives SO fibers their red color). All of these features allow SO fibers to produce large quantities of ATP, which can sustain muscle activity without fatiguing for long periods of time.

The fact that SO fibers can function for long periods without fatiguing makes them useful in maintaining posture, producing isometric contractions, stabilizing bones and joints, and making small movements that happen often but do not require large amounts of energy. They do not produce high tension, and thus they are not used for powerful, fast movements that require high amounts of energy and rapid crossbridge cycling.

FO fibers are sometimes called intermediate fibers because they possess characteristics that are intermediate between fast fibers and slow fibers. They produce ATP relatively quickly, more quickly than SO fibers, and thus can produce relatively high amounts of tension. They are oxidative because they produce ATP aerobically, possess high amounts of mitochondria, and do not fatigue quickly. However, FO fibers do not possess significant myoglobin, giving them a lighter color than the red SO fibers. FO fibers are primarily used for movements, such as walking, that require more energy than postural control but less energy than an explosive movement, such as sprinting. FO fibers are useful for this type of movement because they produce more tension than SO fibers, but they are more fatigue-resistant than FG fibers.

FG fibers primarily use anaerobic glycolysis as their ATP source. They have a large diameter and possess high amounts of glycogen, which is used in glycolysis to generate ATP quickly to produce high levels of tension. Because they do not primarily use aerobic metabolism, they do not possess substantial numbers of mitochondria or significant amounts of myoglobin and therefore have a white color. FG fibers are used to produce rapid, forceful contractions to make quick, powerful movements. These fibers fatigue quickly, permitting them to only be used for short periods. Most muscles possess a mixture of each fiber type. The predominant fiber type in a muscle is determined by the primary function of the muscle.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.