Table of Contents |

The Northern Renaissance paintings of the 16th century were an amalgam of Northern-style symbolism, detail, and textural interests, with the influence of the Italian Renaissance elements of accurate perspective and logical compositions.

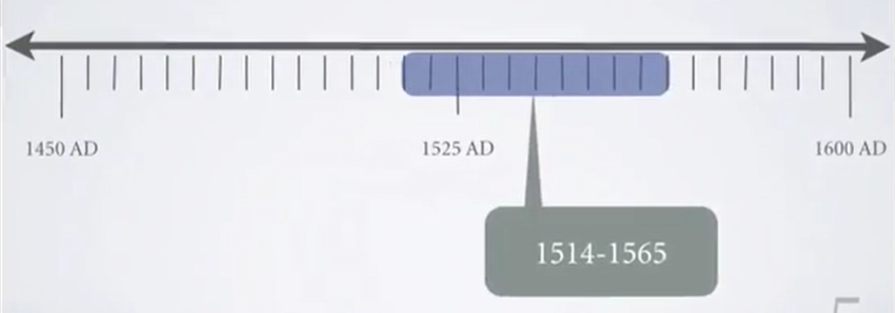

The artwork that you will be looking at today dates from between 1514 and 1565.

The artists whose work you’ll be examining are from Northern Europe, originating from places such as Bree and Antwerp in modern-day Belgium, and Augsburg in modern-day Germany, shown below. Note that the purple area delineates the Holy Roman Empire.

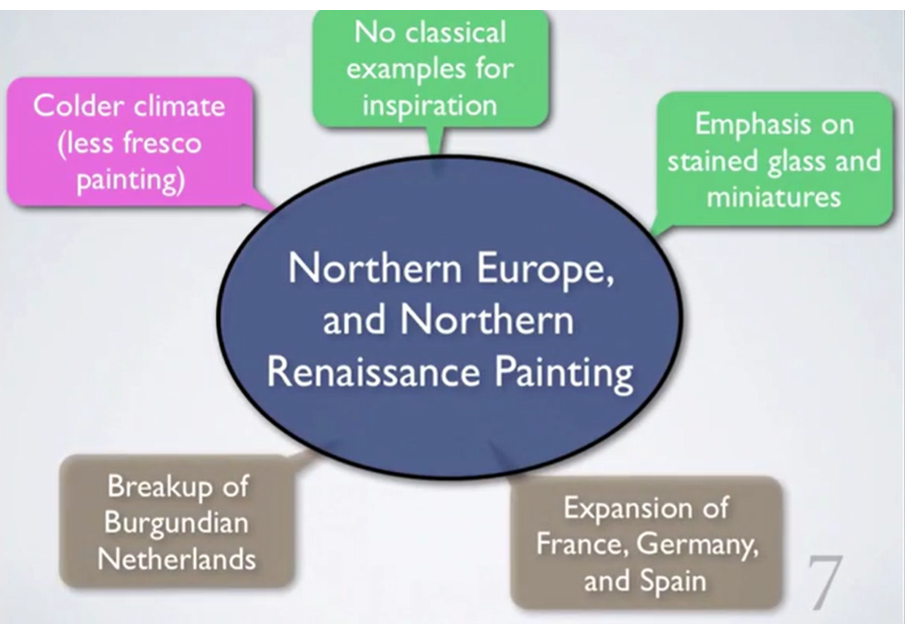

It’s important to remember that art often reflects or is influenced by the political climate of the time—as well as the literal climate of the time—as much as it is by the social trajectory.

The 16th century was a dynamic time in Northern Europe. The Protestant Reformation was beginning, thanks to a rebellious monk named Martin Luther. The artistic and sociopolitical climate of Northern Europe was being influenced by a number of major events:

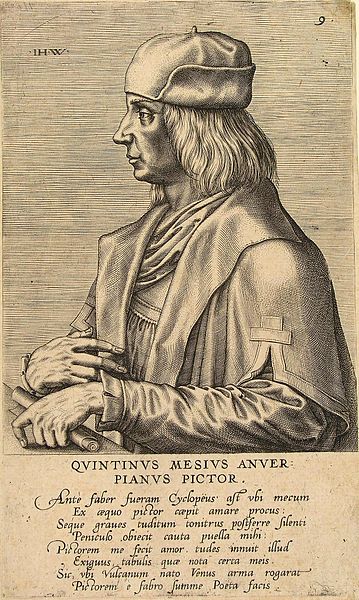

The artist Quentin Massys, shown in the image below, is believed to have begun his career as a blacksmith in his hometown of Leuven before taking up painting and moving to Antwerp, Flanders (modern-day Belgium), where he remained for the rest of his life until his death in 1529.

Massys’ painting of “The Money Changer and His Wife” was almost certainly inspired by an earlier work by the Flemish painter Petrus Christus of a goldsmith in his shop, as well as the increased prosperity that was seen in the Netherlands and Flanders during this time.

1514

Oil on panel

In a typical Northern Renaissance fashion, this painting exemplifies a form of genre painting where the subject matter is something from everyday life. The man is carefully counting and weighing coins, while his wife flips through a book of hours, or illuminated manuscript.

Hans Holbein the Younger—distinguished from, you guessed it, Hans Holbein the Elder—originated from the town of Augsburg in the Holy Roman Empire, in what is today the country of Germany. He was a very accomplished painter, having served the family of Anne Boleyn, and as the court painter for Anne Boleyn’s husband, Henry VIII. Here is his self-portrait:

1542

Augsburg, Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany)

While employed in England, Holbein created one of his most famous paintings, “The French Ambassadors.” Again, in typical Northern Renaissance style, the painting is full of symbolism. However, the influence of the Italian Renaissance is also evident in the careful application of perspective and the logical order of composition. The man on the left is Jean de Dinteville, the French ambassador to England, and the man on his right is his friend, Georges de Selve, a bishop and ambassador to the Catholic Holy See.

1533

Oil on oak

The two men are 28 and 24, respectively, as evident in embossing on the dagger in Dinteville’s right hand, as well as the writing on the Bible underneath de Selve’s right arm. The fabrics are richly textured and realistically rendered, which is a hallmark of the Northern style of painting. Objects in the painting are either humanist or religious in their symbolism, and the most prominent object is the oddly placed and distorted skull.

One of the most well-known genre painters in Northern Europe was the painter, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, shown below in his self-portrait. Originating from Bree in modern-day Belgium, he began his career by imitating the style and subject matter of one of his greatest influences, the artist Hieronymus Bosch.

1565

Bree, Habsburg Netherlands (modern-day Belgium)

He traveled to Italy during his lifetime and was particularly influenced by the landscape of the Italian countryside. He incorporated some of the Italian geography into his landscapes of Flanders, as is evident in this painting, titled “Hunters in the Snow.”

1565

Oil on wood panel

Now, although rolling hills exist in Flanders, mountains do not. This is a depiction of a rather uneventful scene—the return of hunters. However, Brueghel generates interest in the scene in the way he places his figures. The landscape is comprised of foreground and background only. There’s no middle ground, which serves to create a sensation of immediate expansion into the surrounding landscape. It’s a vantage point unique to the observer and an engaging juxtaposition of the daily routine against the backdrop of an expansive, beautifully detailed, Flemish landscape.

Source: This work is adapted from Sophia author Ian McConnell.