Table of Contents |

At times, sending out corporate financial and other types of sensitive data over the internet is the most convenient way to share such information. This is why being able to hide or encode that data with encryption technologies is so vital for shielding it from a company’s competitors, identity thieves, or any other type of attacker. Without encryption, our sensitive files and information may not remain confidential as the data cross the internet.

Encrypting passwords being sent from a workstation to a server when logging in is a basic need for internal networks, and most of today’s network operating systems do it automatically. But legacy protocols like File Transfer Protocol (FTP) and Telnet do not have the ability to encrypt passwords. Most email systems also give users the option to encrypt email messages, and email systems that do not come with encryption abilities of their own often use third-party software packages like Pretty Good Privacy (PGP). And you already know how critical encryption is for data transmission over VPNs. Encryption capability is clearly very important for e-commerce transactions, online banking, and investing.

When using symmetric-key encryption, both the sender and receiver have the same key and use it to encrypt and decrypt all messages. The downside of this technique is that it becomes hard to maintain the security of the key. In contrast, when the keys at each end are different, it is called asymmetric-key encryption. The following sections describe some symmetric-key standards and then compare them to asymmetric-key encryption.

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) is a symmetric-key algorithm that was made a standard back in 1977 by the U.S. government. DES uses lookup and table functions, and it actually works much faster than more complex systems. It uses 56-bit keys. RSA Data Systems once issued a challenge to see if anyone could break the key.

Back then, DES was a great security standard, but the 56-bit key length has proved to be too short.

The Triple Data Encryption Standard (3DES), also a symmetric-key algorithm, was originally developed in the late 1970s, and it became the recommended method of implementing DES encryption in 1999. As its name implies, 3DES is essentially three DES encryption methods combined into one.

3DES encrypts three times, and it allows us to use one, two, or three separate keys. Clearly, going with only one key is the least secure, and opting to use all three keys gives the highest level of security. Three-key 3DES has a key length of 168 bits (56 times 3).

Even now, it is being phased out in favor of faster methods like AES.

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) has been the official symmetric-key encryption standard in the United States since 2002. It specifies key lengths of 128, 192, and 256 bits.

IN CONTEXT

The AES has proven amazingly difficult to crack. Those who try use a popular method involving something known as a side channel attack. This means that instead of going after the cipher directly, they attempt to gather the information they want from the physical implementation of a security system. Hackers attempt to use power consumption, electromagnetic leaks, or timing information (like the number of processor cycles taken to complete the encryption process) to give them critical clues about how to break the AES system. Although it is true that attacks like these are possible to pull off, they are not really practical to clinch over the internet.

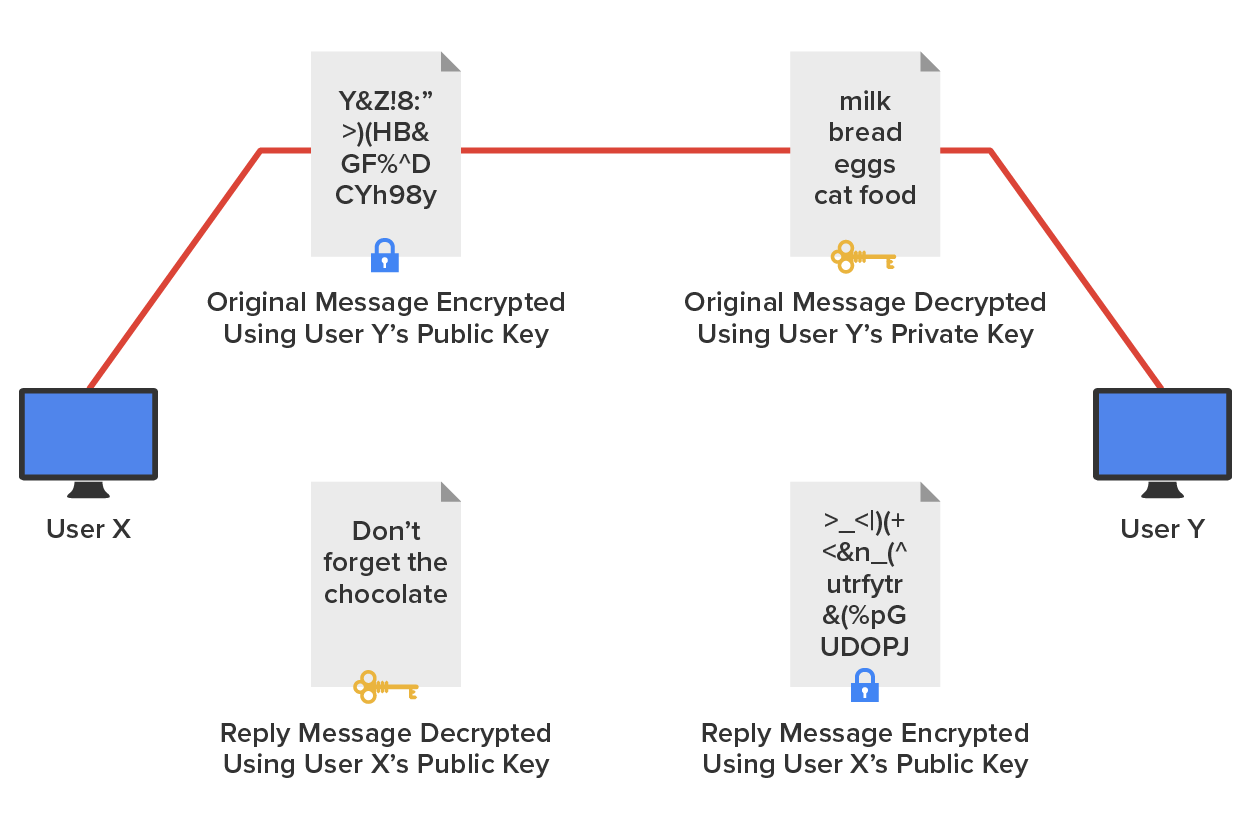

Public-key encryption uses the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, which employs a public key and a private key to encrypt and decrypt data. This is called asymmetric encryption. It works like this: The sending machine’s public key is used to encrypt a message that is decrypted by the receiving machine with its private key. It is a one-way communication, but if the receiver wants to send a return message, it does so via the same process. If the original sender does not have a public key, the message can still be sent with a digital certificate that is often called a digital ID, which verifies the sender of the message.

The diagram below shows public-key-encrypted communication between User X and User Y.

RSA encryption is a public-key algorithm named after the three scientists (Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman) from MIT who created it. They formed a commercial company in 1977 to develop asymmetric keys and nailed several U.S. patents. Their encryption software is used today in electronic commerce protocols.

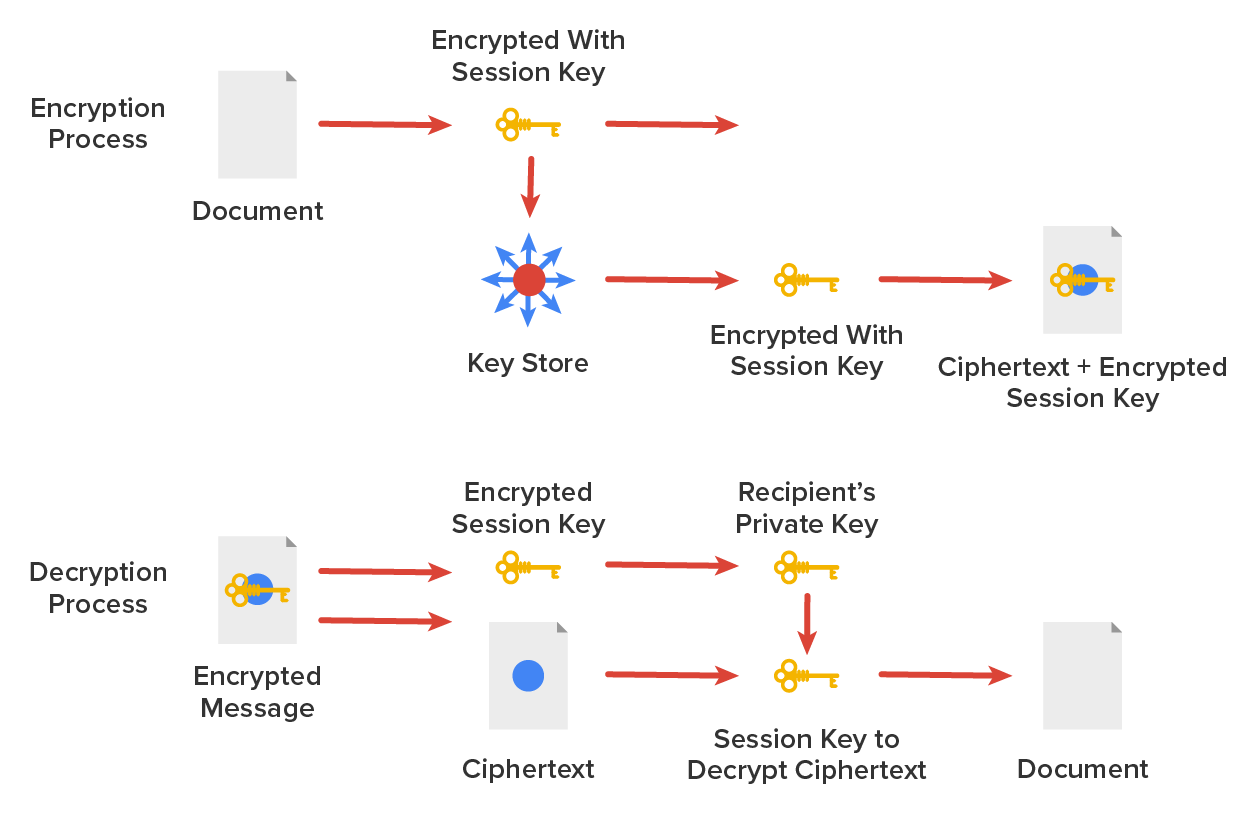

Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) was developed in the early 1990s by Phil Zimmerman (also from MIT), who wrote most of the code for this freely available version of public-key encryption designed to encrypt data for email transmission. Zimmerman basically compared email to postcards, because anyone can read email messages traversing the internet just as they can postcards traveling through the postal service. By contrast, he compared an encrypted message to a letter mailed inside an envelope. The diagram below shows the PGP encryption system.

In the diagram above, the document is encrypted with a session key, which is then encrypted with the public key of the recipient. Then the ciphertext and the encrypted session key are sent to the recipient. Since the recipient is the only person with the matching private key, only they can decrypt the session key and then use it to decrypt the document.

IN CONTEXT

Zimmerman distributed the software for personal use only, and as the name implies, it is really pretty good security. RSA Data Security and the U.S. federal government both had a problem with Zimmerman’s product—the RSA complained about patent infringement, and the government actually decided to prosecute Zimmerman for exporting munitions-grade software. The government eventually dropped the charges, and now a licensing fee is paid to RSA, so today, PGP and other public-key-related products are readily available.

Source: This content and supplemental material has been adapted from CompTIA Network+ Study Guide: Exam N10-007, 4th Edition. Source Lammle: CompTIA Network+ Study Guide: Exam N10-007, 4th Edition - Instructor Companion Site (wiley.com)