Table of Contents |

Together, the extension of railroads into the countryside, the rise of the industrial economy, and the expansion of consumerism transformed rural America. In the South, cotton production reached levels that were unknown prior to the Civil War. In the Midwest, the cultivation of wheat and other grains presented a number of challenges.

The end of slavery did not end cotton cultivation in the South. The growth of Northern textile mills and the railroads as well as the depressed state of the Southern economy following the Civil War ensured the continued importance of cotton in Southern agriculture.

Many poor White farmers, as well as thousands of formerly enslaved people, lacked sufficient land, money, and tools to raise cotton. A number of merchants, store owners, and former planters (who were eager to put their land back into production) were willing to help them—for a price.

In the crop-lien system, lenders agreed to extend credit to poor farmers in return for part of their harvest. The lenders—the merchants, store owners and former planters mentioned above—charged high-interest rates, which made it difficult for farmers to remain independent when they had a poor harvest and could not pay their debts.

Sharecropping also took root throughout the South. Landowners (including former plantation owners) rented their land to poor farmers. They provided their tenants with nearly everything they needed to raise a crop, including farm implements, animals, and seed. In return, the sharecroppers paid their rent with the crops they grew, especially cotton.

Under the crop-lien and sharecropping systems, poor Southern farmers—White and Black—endured a vicious cycle. Their debt payments left them with little for basic necessities and farm improvements. In order to satisfy their obligations, farmers had no choice but to grow more cotton: the only crop of value. As a result, they could not devote much of their land to food crops, which meant they had to rely on store owners and creditors to provide for their families. In this way, many farmers were trapped in a never-ending cycle of debt, unable to buy the land they farmed or to stop working for their creditors.

Farmers in the Midwest also faced challenges, most notably those associated with wheat production and the railroads. Newly developed implements like steel plows and mechanical reapers enabled Midwestern farmers to increase crop yields. However, when they took their wheat to a nearby grain elevator for shipment, they found that they had little say in how much it was worth.

Farmers took their wheat to grain elevators where they met grain buyers, who often represented firms based in Chicago. Buyers examined the grain and divided it into grades denoting type and quality (e.g., No. 1 spring wheat and No. 2 winter wheat). Farmers had no say in this process or any influence on the price they received.

As a result of this system, farmers increased wheat production in an attempt to earn enough to pay their debts and earn a living. This began a vicious cycle: the more wheat they produced, the less they earned, as prices dropped when the market became saturated.

One thing that Southern and Midwestern farmers had in common was debt. Farm implements and other necessities were expensive and, for most of the year (with the exception of harvest time), farmers were cash-poor. This required them to buy on credit at high-interest rates. They had little influence on how much of a profit they could make since prices were set without their input, and were beyond their control.

Like the workers who formed unions to protect their interests, Midwestern and Southern farmers recognized the benefits of organization. They understood that collective action could influence railroads, creditors, and, when necessary, the federal government to address their concerns.

Grange members believed that farmers could help themselves by creating cooperatives to pool resources and obtain lower shipping rates from the railroads, and better prices on seed, fertilizer, machinery, and so forth. They believed that the cooperatives would enable farmers to regulate production and deal with railroads, creditors, and other businesses as equals.

At the state level, especially in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, and Iowa, Grange members influenced the passage of “Granger Laws,” which empowered state governments to regulate the prices that grain elevator operators charged farmers. The Grange also supported a political party—the Greenback Party—which was briefly successful during the mid-1870s when at least 15 of its members were elected to Congress, and many others were candidates in local and state elections.

The Party’s success was short-lived. In the Wabash v. Illinois case of 1886, which was brought by the Wabash, St. Louis, and Pacific Railroad Company, the Supreme Court ruled against Illinois’ Granger Laws by arguing that the states did not have the authority to control interstate commerce. The Greenback Party ceased to be a viable third party in 1888, when only seven delegates attended its convention.

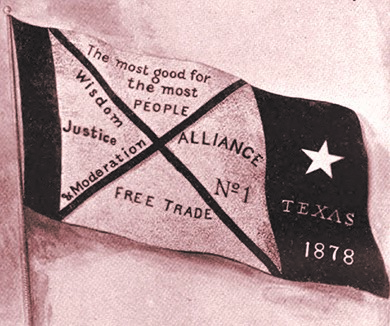

The Farmers’ Alliance, a conglomeration of three regional alliances formed in the mid-1880s, took root in the wake of the Grange movement.

In 1890, Dr. Charles Macune, who led the Southern Alliance (which was based in Texas and had over 100,000 members in 1886), urged the creation of a national Farmers’ Alliance consisting of his organization, the Northwest Alliance, which consisted of Midwestern farmers (many of them former Grangers), and the Colored Alliance, the largest African American organization in the United States with over one million members. The Farmers’ Alliance brought together over 2.5 million American farmers.

The goals of the Farmers’ Alliance were similar to those of the Grange and the Greenback Party. They included greater regulation of railroad shipping rates and a monetary policy that decreased interest rates and provided more cash to farmers. However, the most innovative reform proposed by the Farmers’ Alliance was the subtreasury plan.

The plan called for the federal government to play a greater role in the regulation of the economy. Farmers would store their crops in government warehouses (or “subtreasuries”) and, in return, the government would provide credit to farmers in the form of “greenbacks.” This would enable the farmers to settle their debts and purchase goods.

While the crops were stored in the subtreasuries, prices would increase due to federal control of supply—removing the influence of the railroads and other middlemen. When market prices rose to a satisfactory level, farmers would withdraw their crops, sell them at a higher price, and repay the government loan. They would be debt free and would also have earned a profit.

During the Gilded Age, the federal government was unwilling to consider a program as radical as the Subtreasury Plan. It also refused to adopt a more flexible currency (i.e., “greenbacks” backed by gold or silver). At the same time, the Supreme Court overruled the Granger Laws. All of this frustrated farmers. In 1891, Charles Macune and other Farmers’ Alliance leaders launched a political party—The People’s Party, otherwise known as the Populist Party—to elect representatives who would enact real change at the state and federal levels. As the 1892 presidential election approached, the Populists nominated James B. Weaver for President, and supported a number of other candidates in state and congressional elections.

During the Populists’ national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, in the summer of 1892, the party agreed upon one of the most revolutionary documents in American history: the Omaha Platform.

Written by Ignatius Donnelly, who had lectured Farmers’ Alliance members in Minnesota since the late 1880s, the platform vilified railroad owners, bankers, and big businessmen for being part of a conspiracy to control farmers. It criticized the government for ignoring the plight of farmers and others who were struggling in the industrial economy, and referred to Democrats and Republicans as “two great political parties for power and plunder….”

To benefit farmers, the platform called for the adoption of the Subtreasury Plan and other financial reforms, including a graduated income tax. It proposed government ownership of all railroads. Together, the platform’s financial and transportation proposals called for a more proactive federal government; one that supported the economic and social welfare of farmers and other productive workers.

The platform also proposed changes designed to expand the democratic process. To undermine political machines, the Populists supported the secret ballot and reforms including initiatives and referendums. Initiatives empower citizens to propose legislative changes on the ballot via petition. Referendums enable voters to approve or reject legislation that is already in effect. To solicit the support of unions, the platform called for an 8-hour workday.

James B. Weaver finished a distant third in the election of 1892 (although he received a respectable one million votes). Democrat Grover Cleveland won a tight race against Benjamin Harrison. Still, the Populist Party made significant gains in congressional and state elections.

EXAMPLE

In Kansas, the Populists won the gubernatorial election and gained a majority in the state house and senate.Rather than being disappointed over losing the presidential race, many Populists were pleased by their accomplishments in the 1892 elections. They immediately began working towards the 1896 presidential election, hoping to build a broader coalition of support, including industrial workers.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL