Table of Contents |

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, he faced one of the worst crises in the country’s banking history. Over 5,000 banks had closed. States including New York and Illinois had ordered all banks within their borders to close to prevent additional bank runs.

Within 48 hours of his inauguration, Roosevelt proclaimed a bank holiday, which temporarily halted bank operations throughout the nation, and called Congress into a special session to address the crisis. Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act, which Roosevelt signed into law on March 9, 1933, only 8 hours after a draft proposal was presented to Congress by the administration.

The act implemented two major changes:

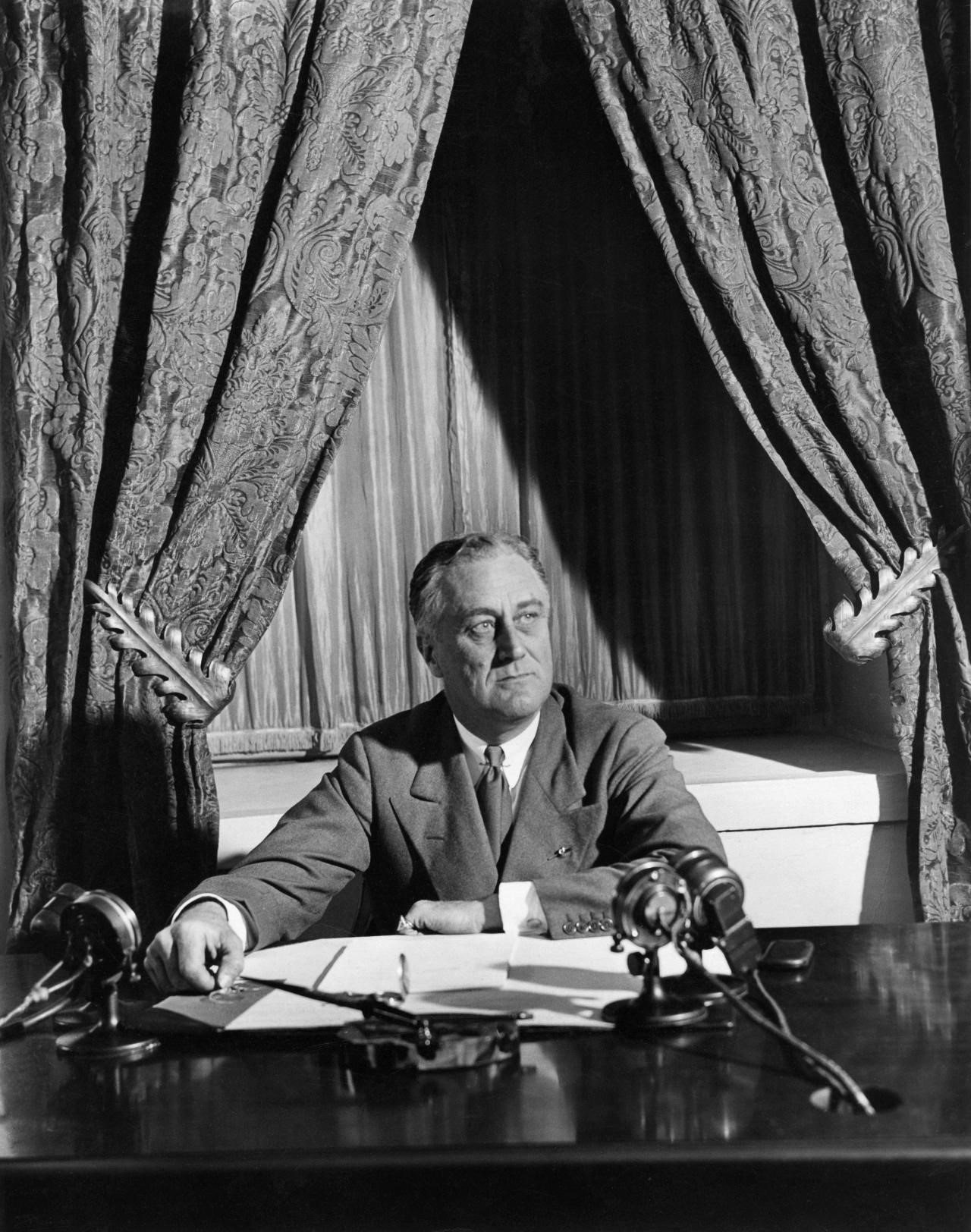

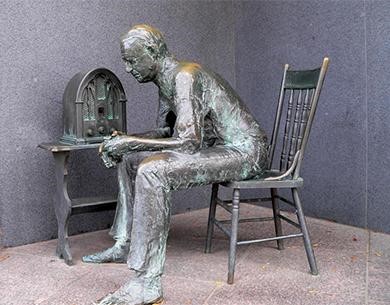

On March 12, before the banks reopened, Roosevelt delivered his first “fireside chat.”

Additional Resource

Listen to an audio recording of FDR’s first fireside chat from the Miller Center.

In the first “chat,” he opened by stating, “I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking.” Roosevelt explained what the bank examiners had been doing during the previous week. He assured listeners that any bank that opened the next day (or in the coming days) had the federal government’s stamp of approval. He asserted that this was something that the federal government had to do, saying, “We had a bad banking situation . . . . It was the Government’s job to straighten out this situation and to do it as quickly as possible—and the job is being performed.”

The address underscored Roosevelt’s savvy in communicating with the American people. He explained complex financial and legal concepts in understandable terms and complimented citizens on their “intelligent support” of the government’s efforts. Most importantly, he inspired confidence by closing his address as follows:

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat”

“Let us unite in banishing fear. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. It is your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail.”

The combination of the Emergency Banking Act and the first fireside chat worked wonders. Consumer confidence returned, and, within weeks, almost $1 billion in cash and gold emerged from under mattresses and bookshelves and was redeposited in the nation’s banks.

When the banking crisis ended, Congress moved to implement permanent reforms of the system, many of which are still in effect today. The most notable of these was the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, which Roosevelt approved in June 1933.

In addition to resolving the banking crisis, the First New Deal advanced legislation in two key areas: relief and recovery. Roosevelt’s predecessor, Herbert Hoover, was reluctant to provide direct federal relief to unemployed Americans. Roosevelt recognized that millions of the unemployed required relief—including jobs—more quickly than the private sector could provide them.

Beginning in late March of 1933, Roosevelt approved several initiatives that made the federal government a provider of unemployment relief. The first was the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA).

Roosevelt initially authorized $500 million in direct grants to the states. However, state and county offices (already overburdened as a result of the Depression) were unable to screen recipients and distribute relief. Local political organizations pocketed some of the federal funds instead of using them to create relief programs.

In response, the federal government took steps to create jobs by organizing public works agencies and work relief programs. The agencies and programs hired unemployed workers. One of the most notable agencies was the Civil Works Administration (CWA).

Organized in November 1933, the CWA employed more than 4 million Americans by January 1934. Workers repaired bridges, built roads and airports, and completed other public projects.

Another notable work program was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Among the most popular New Deal programs, the CCC employed young (aged 14 to 24), employed men. Earning $30 a month (a portion of which they sent to their families), CCC employees did a variety of outdoor jobs, including planting trees, constructing dams, fighting forest fires, restoring historic sites and parks, and building roads and infrastructure that Americans continue to use today. More than 3 million young men had worked for the CCC by 1942, when the program ended.

Industrial and agricultural recovery were the other key areas that the First New Deal addressed. The Roosevelt administration drafted two of the most significant pieces of New Deal legislation to deal with the underlying problems in the economy. The first was the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA).

Farms around the country struggled—and failed—during the Great Depression. In the Great Plains, the drought severely limited farmers’ ability to raise crops, while in the South, abundant harvests led to prices that were too low for farmers to earn a living by selling them. The AAA provided direct financial relief and paid farmers to reduce the production of certain crops, including wheat, cotton, corn, and hogs.

EXAMPLE

Farmers received 30 cents per bushel for corn they did not grow. Hog farmers were paid $5 per head for hogs not raised.The AAA was a bold attempt by the federal government to help farmers address the systemic problem of overproduction and the lower commodity prices resulting from it. However, there was an excess of some agricultural products, particularly cotton, and hogs before the AAA went into effect.

EXAMPLE

This led the federal government to order 10 million acres of cotton to be plowed under and the butchering of 6 million baby pigs (and 200,000 sows).Although the AAA improved prices (e.g., the price of cotton increased from 6 to 12 cents per pound), the destruction of agricultural products was deeply problematic. Critics pointed out that the government was destroying food to drive up prices, while some citizens starved.

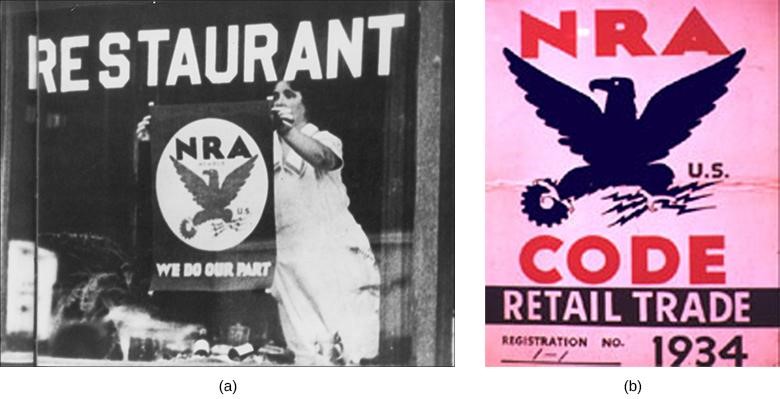

A second significant measure, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), sought to stabilize the manufacturing sector and place it on the road to recovery.

New Deal officials believed that supporting collaboration between businesses would enable them to stabilize prices and production levels. Some officials believed these collaborations would protect workers from entering unfair agreements.

A new government agency, the National Recovery Administration (NRA), was central to the implementation of NIRA. It mandated that businesses accept a code that included limits for minimum wage and maximum work hours. Industries were required to adopt “codes of fair practice” that upheld workers’ rights to organize and collectively bargain to ensure that wages increased as prices rose.

The NRA created over 500 codes for industries—a large and growing number of regulations that led to unforeseen problems. While codes for key industries (e.g., automotive and steel) made sense, similar codes for dog food manufacturers and shops that made shoulder pads for women’s clothing, for example, did not.

The Public Works Administration (PWA) produced some of the most lasting benefits of NIRA.

With an appropriation of $3.3 billion, the PWA completed over 34,000 public works projects, including the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and the Queens–Midtown Tunnel in New York. Between 1933 and 1939, the PWA accounted for the construction of over one third of all new hospitals and 70% of all new public schools in the United States.

The First New Deal was far from perfect, but Roosevelt’s quickly implemented policies reversed the economy’s slide and restructured Americans’ relationship with the federal government.

The Emergency Banking Act infused ailing banks with new capital. Work relief programs like the CWA and the CCC offered direct relief to the unemployed. The AAA and NIRA provided incentives and organizational methods to farmers and industries to put the economy on a path toward recovery.

Roosevelt did not conceive or implement the First New Deal on his own. At times, it seemed to consist of a series of disjointed efforts based on different (and sometimes baffling) assumptions. For example, a program designed to decrease production (or make payments in return for no production) in an attempt to set prices on industrial goods and raise the prices of crops seemed counterintuitive to some manufacturers and farmers.

However, these programs were designed to combat what Roosevelt and his advisors believed had caused the Great Depression: abuses on the part of a small group of bankers and businessmen, aided by Republican policies that built wealth for a few at the expense of many. They believed that the solutions would be accomplished by reforming the banking system, strengthening labor’s bargaining power, and adjusting the production and consumption of agricultural and industrial goods.

For the first time since the Progressive Era, many Americans looked to the government for direction and support. Progressives implemented reforms in response to the problems of the Gilded Age and World War I; the Great Depression created an opportunity for even greater reform. Progressivism focused on perfecting democracy and social justice. The New Deal created government structures and agencies that regulated the economy. By means of work relief programs and other measures, the New Deal established safety nets for the victims of the Great Depression. In these ways, the New Deal established the foundation of the modern welfare state in America.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933, Miller Center, Retrieved from millercenter.org