Table of Contents |

In the previous tutorial, we looked at types of conflict like personality differences, differences of opinion, and behavioral differences. Misunderstandings, lack of clear communication, and conflicting priorities can lead to tension among coworkers. Issues related to power dynamics, competition for resources, or unequal workloads can also ignite conflicts. Cultural diversity, conflicting values, and ethical dilemmas can further exacerbate discord. Effective conflict resolution strategies and open communication are essential to address and mitigate these common sources of workplace conflict. In this tutorial, we will focus on the conflicts that are directly related to the work and the organization itself.

Sociologist Robert Miles provides a list of some of the organizational qualities that cause conflict.

| Organizational Quality | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Task Interdependencies | The first source of conflict is in task interdependencies, or the way people work together and collaborate. The more task interdependence among individuals and groups, the greater the likelihood of conflict. This happens because the more people rely on each other, the more one person or group will fall short of another person or group’s expectation; it also happens because as the work together intensifies, the conflict is harder to avoid and can itself become more intense. | Raheem is a word processing specialist who standardizes documents and prepares them for printing; he then hands them off to the printing department. He has an ongoing conflict with Ellena in the printing department because he hands in files at the last minute and expects a quick turnaround. She keeps reminding him that he needs to give her 5 days' notice for any project. He tells her he wishes he could, but he himself often doesn’t get them from his manager until the last minute. The more work he sends her way, the more conflict they have. |

| Status Inconsistencies | A second source of conflict is status inconsistencies among the parties involved. | The salaried employees in an organization have flexible schedules that allow them to come in late, leave early, or even run errands during the day. The hourly employees who have to clock in and out find this unfair. |

| Jurisdictional Ambiguities | Conflict can also emerge from jurisdictional ambiguities—that is, any situation where it is not clear who is in charge or who is accountable. | For example, many organizations use an employee selection procedure in which applicants are evaluated both by the personnel department and by the department in which the applicant would actually work. Because both departments are involved in the hiring process, what happens when one department wants to hire an individual, but the other department does not? |

| Communication Problems | A lot of conflict is due to communication issues, such as when something is not communicated clearly, in a timely manner, or respectfully. It can also refer to when something is not communicated at all. | Leadership is in discussions behind closed doors about some planned layoffs as a travel agency suffers through a prolonged downturn in business. The staff understands the need to eliminate some positions but wants as much notice as possible. They resent being locked out of the discussions and not being given meaningful updates. |

| Dependence on a Common Resource Pool | Another previously discussed factor that contributes to conflict is dependence on common resource pools. Whenever several departments must compete for scarce resources, conflict is almost inevitable. When resources are limited, a zero-sum game exists in which someone wins, and invariably, someone loses. | An ongoing source of conflict in a real estate office is the availability of paper and toner in the shared copy room. As soon as it is restocked, some agents will hurry in to do as much copying as they can before the supply runs out—which only makes the issue worse. |

| Lack of Common Performance Standards | Each department may have its own standards for excellence, such as revenue generated for the sales department, or efficiency and lack of errors in the production department. However, these differences can lead to conflict if they are naturally in conflict with one another. |

A production department is often rewarded for their efficiency, and this efficiency is facilitated by the long-term production of a few products and by having resources on hand. Sales departments, on the other hand, are often rewarded for overall sales, which may be highly variable in a volatile market. They may quickly sell a product that is not on hand, and for which resources are in short supply, while failing to sell a product that the production team has stocked up on. In such situations, conflict arises as each unit attempts to meet its own performance criteria. |

| Individual Differences |

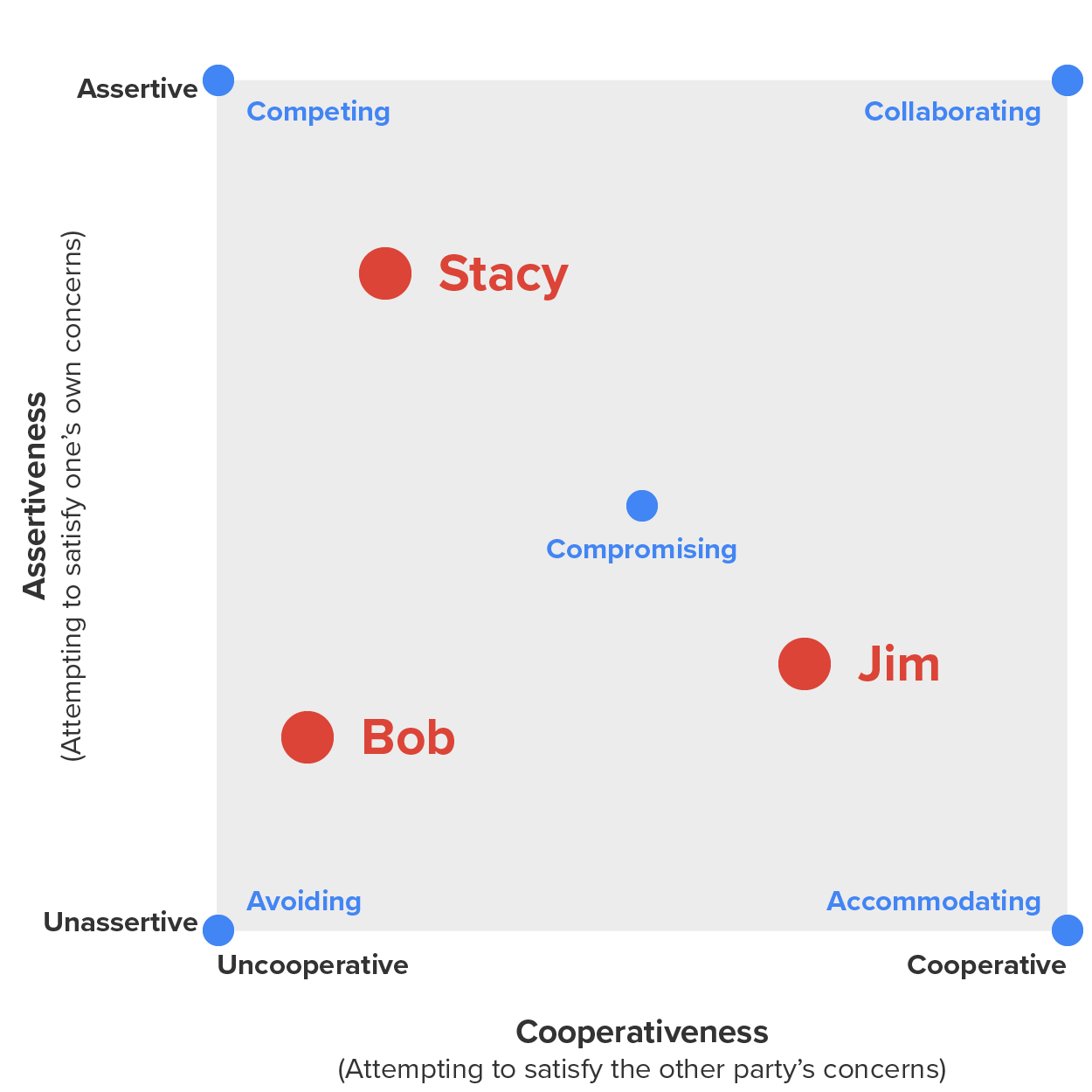

As we discussed in the previous tutorial, some conflict is caused by interpersonal differences. They may not be due to the organization itself (though they still affect the organization). However, sometimes they are directly related to the job, such as people with different skill sets doing the same job, or people with different work styles. Another key difference is the way people handle conflict. Some may seek to “win” any disagreement, or at least want a clear “winner” and “loser.” That is, they want one person to be proven right, and the other wrong. Others have a higher tolerance for ambiguity and more willingness to compromise. A conflict is likely to get worse if the parties can’t even agree on how to resolve the conflict. |

Bob and Stacey are both hired to test and debug code for a software company. While both are knowledgeable of the programming language, Stacey has more developed skills specifically in finding and fixing bugs. She works methodologically and documents things thoroughly. Bob has a different approach, stress testing and trying to “break” the program so he can discover its vulnerabilities. He takes good notes when he finds the errors but is less diligent in documenting all of his trials that don’t reveal errors. Stacey finds his process random and undisciplined. When she confronts him, he says, “You do you, and I’ll do me.” The conflict deepens when she asks their manager, Jim, to intervene. Jim says it’s OK for Bob to take an unconventional approach and tells Stacey to “stay in her lane.” |

Having examined specific factors that are known to cause conflict, we can ask how conflict comes about in organizations. One commonly accepted model of the conflict process was developed by Kenneth Thomas.

| Stage | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Frustration | As we have seen, conflict situations originate when an individual or group feels frustration in the pursuit of goals. This frustration may be caused by a wide variety of factors, as described earlier, and may be as simple as wanting a quiet and peaceful office environment or as serious as wanting the organization to go in a different direction. | Let’s continue to look at the example of Bob and Stacey, who work together debugging software applications. Stacey feels Bob’s work is less disciplined than her own, frustrating her goal for the department to be successful, and she feels it’s unfair, forcing her to do more work. |

| Stage 2: Conceptualization | In the conceptualization stage of the model, parties to the conflict attempt to understand the nature of the problem, what they themselves want as a resolution, what they think their opponents want as a resolution, and various strategies they feel each side may employ in resolving the conflict. This stage is really the problem-solving and strategy phase. | As we described, Stacey feels the correct resolution is for the department to follow the same procedures for discovering and documenting bugs in the software. She has conceptualized (perhaps unfairly) that Bob wants the job to be easy and fun. She also knows that Bob isn’t interested in her procedures or her opinions. |

| Stage 3: Behavior |

As a result of the conceptualization process, parties decide how to deal with the conflict. Thomas categorizes these as competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating.

We will explore these strategies further below, but the fundamental decision is how to address the conflict, and what tactics to use to do so. However, note that some behaviors do not address the conflict at all—such as simply avoiding it or accommodating it. These are still considered “conflict resolution,” in the broadest sense of the term. |

Stacey had several behavioral options. She could have asked that she and Bob work on different projects so she doesn’t have to worry about his unorthodox methods (avoiding), or even try to see his ways as bringing strengths to the department (accommodating). However, she wanted to do things her way and so chose the behavior of being competitive. This is discussed further below. |

| Stage 4: Outcome | Finally, as a result of efforts to resolve the conflict, both sides determine the extent to which a satisfactory resolution or outcome has been achieved. Where one party to the conflict does not feel satisfied or feels only partially satisfied, the seeds of discontent are sown for a later conflict. | Stacey tried to resolve the conflict, and her manager, Jim, may feel that it is resolved. However, Stacey is still dissatisfied, and the conflict will fester. Even if they finish one project satisfactorily, the next will bring up new conflicts. |

The choice how to respond to conflict depends on the seriousness of the situation and the goals of the party. According to Thomas’s model, this depends on two spectra:

Click image to open an enlarged view. |

Note that so far, this is merely describing conflict—how it emerges and how people handle it—and does not suggest that one way or another is “best.” Though it may seem like “collaboration” is always the best option, since all parties are satisfied, Thomas suggests that not all conflict needs to be addressed. Below are some suggestions of which approach is right for different situations.

| Conflict-Handling Modes | Appropriate Situations |

|---|---|

| Competing |

|

| Collaborating |

|

| Compromising |

|

| Avoiding |

|

| Accommodating |

|

One final note about this model is that it relies on perceptions people have about their own behaviors compared to those they’ve been in conflict with. However, these are subject to personal bias. For example, one study revealed that executives typically described themselves as using collaboration or compromise to resolve conflict and typically described those they’ve been in conflict with as competitive. In other words, the executives underestimated their opponents’ concern as uncompromising. Simultaneously, the executives had flattering portraits of their own willingness to satisfy both sides in a dispute.

While this table shows when to pursue different kinds of collaboration, it doesn’t tell us how. We will discuss this in the final two tutorials of this challenge. In the next tutorial, we will look at some unsuccessful strategies for managing conflict and some general managerial practices that can prevent or reduce conflict from emerging.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR". ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ORGANIZATIONAL-BEHAVIOR/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.