Table of Contents |

Regulation is critical to cells ranging from individual cells with simple life cycles to complex cells in large multicellular organisms. Effective regulation means that cells can produce compounds only when they need them, saving energy and materials that might otherwise be wasted. It also allows cells to be specialized.

Think about the difference between a skin cell and a muscle cell. They serve very different functions and look different but have the same genes. The reason that they are so different is that different genes are turned on and off to give them different structures and capabilities.

Genomic DNA contains structural and regulatory genes. Structural genes encode products such as enzymes and cellular components. Regulatory genes encode products that regulate gene expression.

Improper regulation can be associated with a variety of problems, including human diseases. For example, cancer develops when the cell cycle is not regulated properly. This can happen when signals that promote cell division are produced inappropriately, signals that inhibit cell division fail to function, or a combination of both. When pathogens cause infections, they engage in complex interactions that include both the pathogen and its host turning genes on and off as needed.

Although there are some similarities in prokaryotic and eukaryotic gene regulation, eukaryotic gene regulation is complicated by the separation of transcription and translation in space and time. Remember, transcription occurs in the nucleus and must be followed by both RNA processing and transport to the cytoplasm before translation can occur in eukaryotes.

In prokaryotes, most regulation occurs through transcriptional control. This is highly effective in conserving materials and energy because transcription does not start at all if the product is not needed.

In eukaryotes, regulation is often finely tuned at multiple levels. Eukaryotes regulate the initiation of transcription, but also have multiple important post-transcriptional mechanisms of regulation.

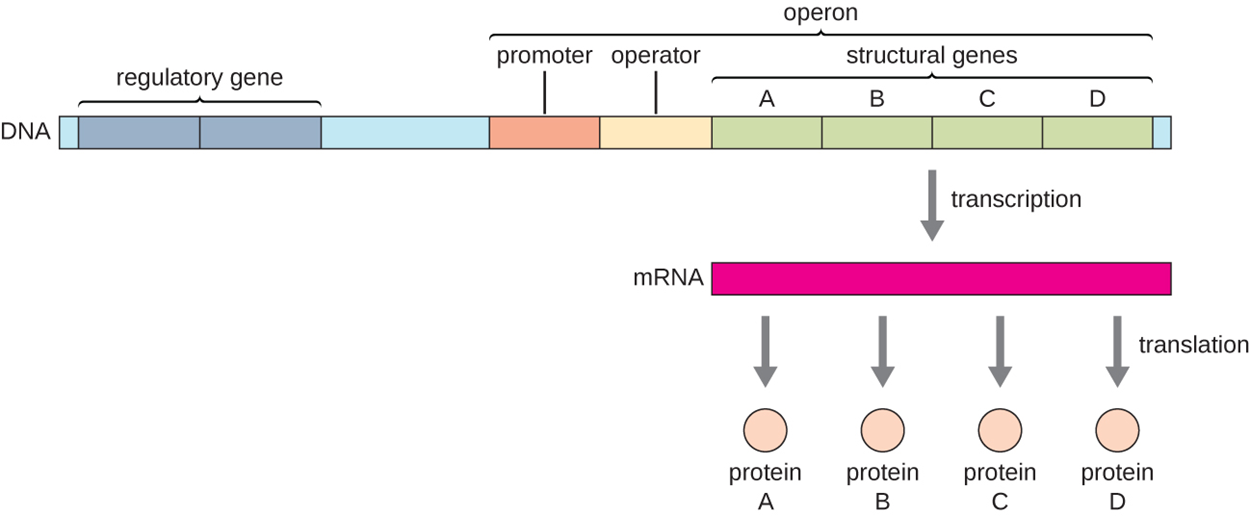

In prokaryotes, operons are essential for regulation. The image below shows an example of an operon, which is a block of regulatory DNA and structural genes that are expressed together. These structural genes generally have related functions. In the operon below, note the regulatory region consisting of a promoter to which RNA polymerase binds and an operator. Molecules can bind to the operator to influence gene expression. In this operon, there are four structural genes labeled A through D that are all transcribed to a single mRNA (called polycistronic as it contains multiple genes). This means that turning one operon on or off can control the production of a set of related proteins.

Transcription factors (proteins encoded by regulatory genes) bind to the regulatory region and influence the binding of RNA polymerase. They can inhibit or promote transcription.

A repressor is a transcription factor that suppresses transcription of a gene in response to an external stimulus by binding to the operator. The operator is located between the RNA polymerase binding site of the promoter and the transcriptional start site of the first structural gene, so the binding of a repressor physically blocks RNA polymerase from binding to begin transcription.

An activator is a transcription factor that increases the transcription of a gene in response to an external stimulus by facilitating RNA polymerase binding to the promoter. Therefore, activators stimulate gene expression.

An inducer is a small molecule that activates transcription by either disabling a repressor or increasing the activity of an activator.

Although many genes are regulated, some gene products are needed continuously and do not need precise regulation. Constitutive expression means that genes are expressed at all times to provide constant intermediate levels of the protein products. These genes encode enzymes involved in cellular maintenance such as DNA replication, repair, and expression, as well as enzymes involved in core metabolism.

Some operons are inducible (meaning that they are turned off by default and must be turned on as needed) whereas others are repressible (meaning that they are turned on by default and must be turned off as needed).

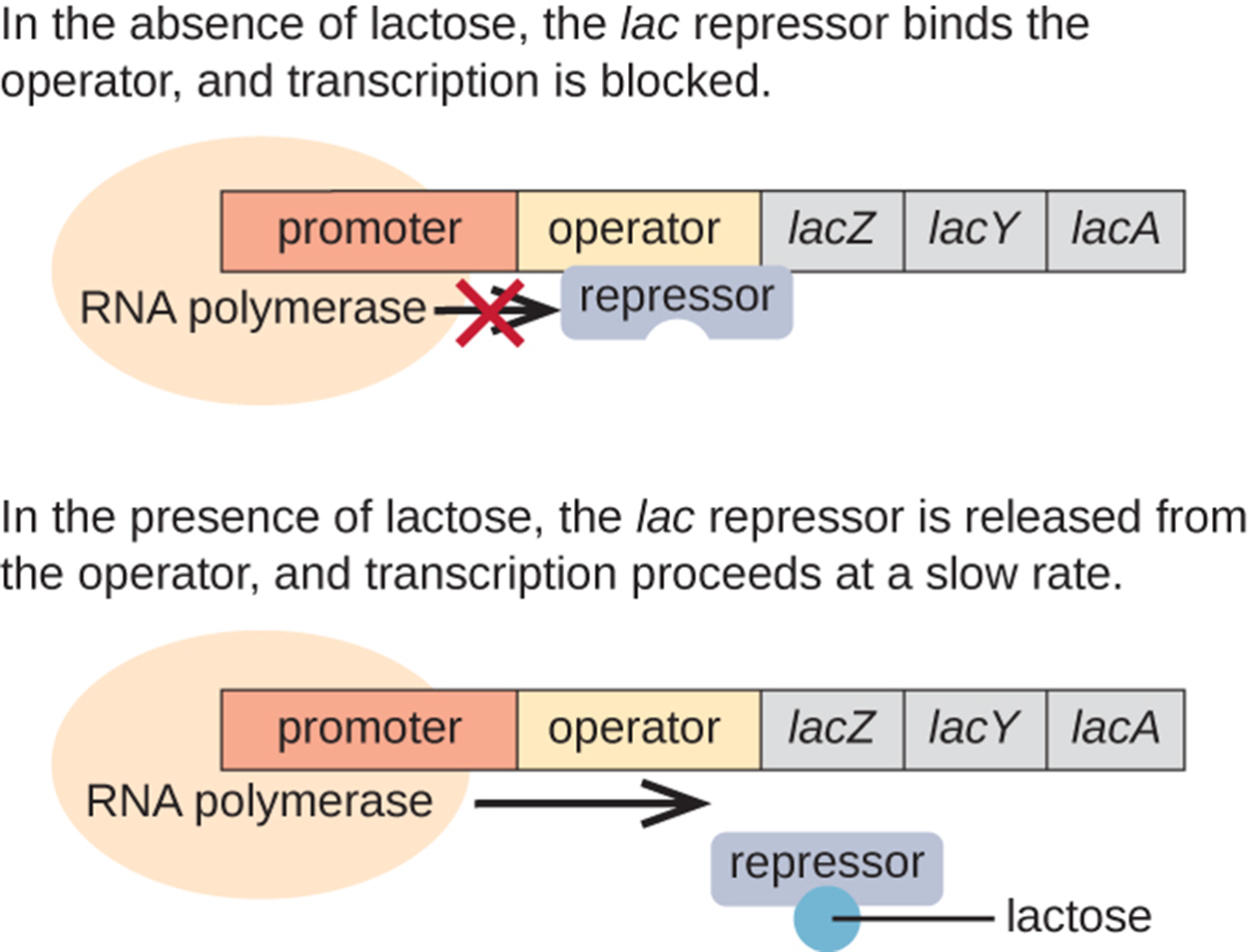

The lac operon is an example of an inducible operon. The purpose of the operon is to produce the enzymes needed to metabolize lactose, but to do so only when lactose is present. In the absence of lactose, the operon is turned off. As shown in the image below, a repressor binds to the operator when lactose is not present. When lactose is present, a closely related molecule (allolactose) binds to the repressor and prevents the repressor from binding to the operator. Therefore, RNA polymerase can attach to the promoter and begin transcription of the three structural genes. These genes have functions related to lactose use.

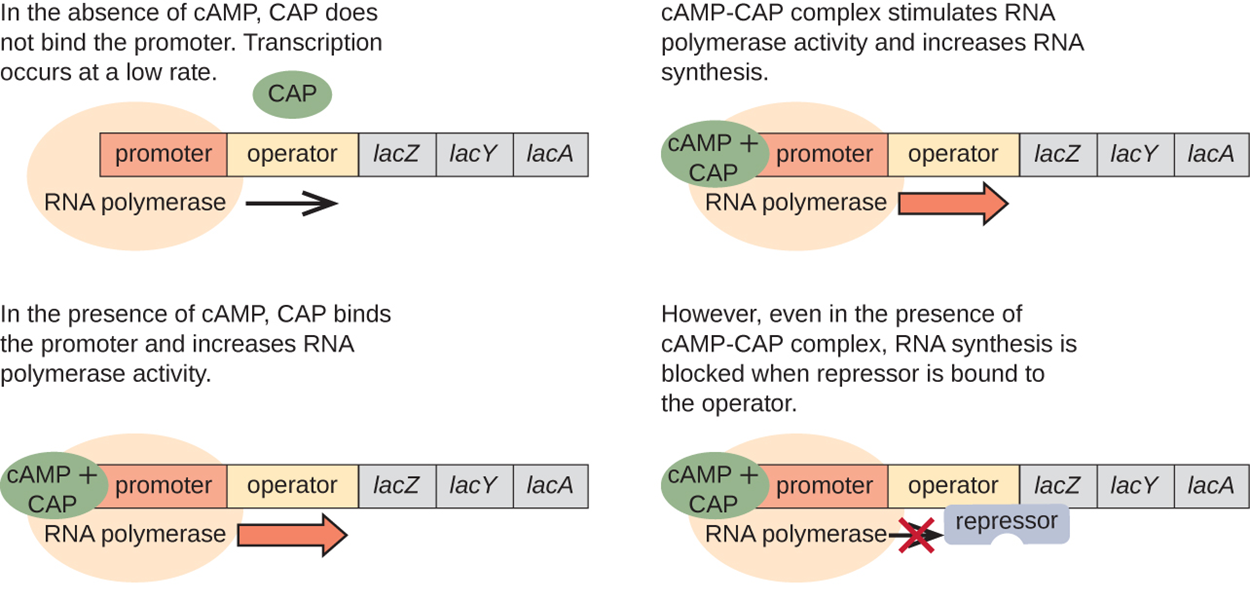

Expression of the lac operon is also influenced by the presence or absence of glucose. If glucose and lactose are both present, the repressor is unable to bind, but the structural genes are still not expressed. Instead, the bacterium consumes glucose first and then begins to express the genes to consume lactose after glucose concentrations have dropped.

The reason for this phenomenon is that glucose levels are related to the levels of catabolite activator protein (CAP). When glucose levels drop, cells produce less ATP from catabolism and enzyme IIA (EIIA) becomes phosphorylated. Phosphorylated EIIA activates adenylyl cyclase, which converts some of the remaining ATP to cyclic AMP (cAMP). Therefore, cAMP levels rise as glucose levels fall.

Accumulating cAMP binds to CAP, also known as cAMP receptor protein. The complex binds to the promoter region of the lac operon upstream of the RNA polymerase binding site in the promoter. Binding of the CAP–cAMP complex to this site increases the binding ability of RNA polymerase and therefore increases transcription.

When glucose levels are low, there is more ATP and therefore less cAMP to bind to CAP. Because there is less CAP–cAMP complex to bind to the promoter region of the lac operon, binding of RNA polymerase is inhibited.

A summary of this process is shown in the image and steps below.

The table below summarizes how different conditions affect transcription of the lac operon.

| Conditions Affecting Transcription of the lac Operon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | CAP binds | Lactose | Repressor binds | Transcription |

| + | – | – | + | No |

| + | – | + | – | Some |

| – | + | – | + | No |

| – | + | + | – | Yes |

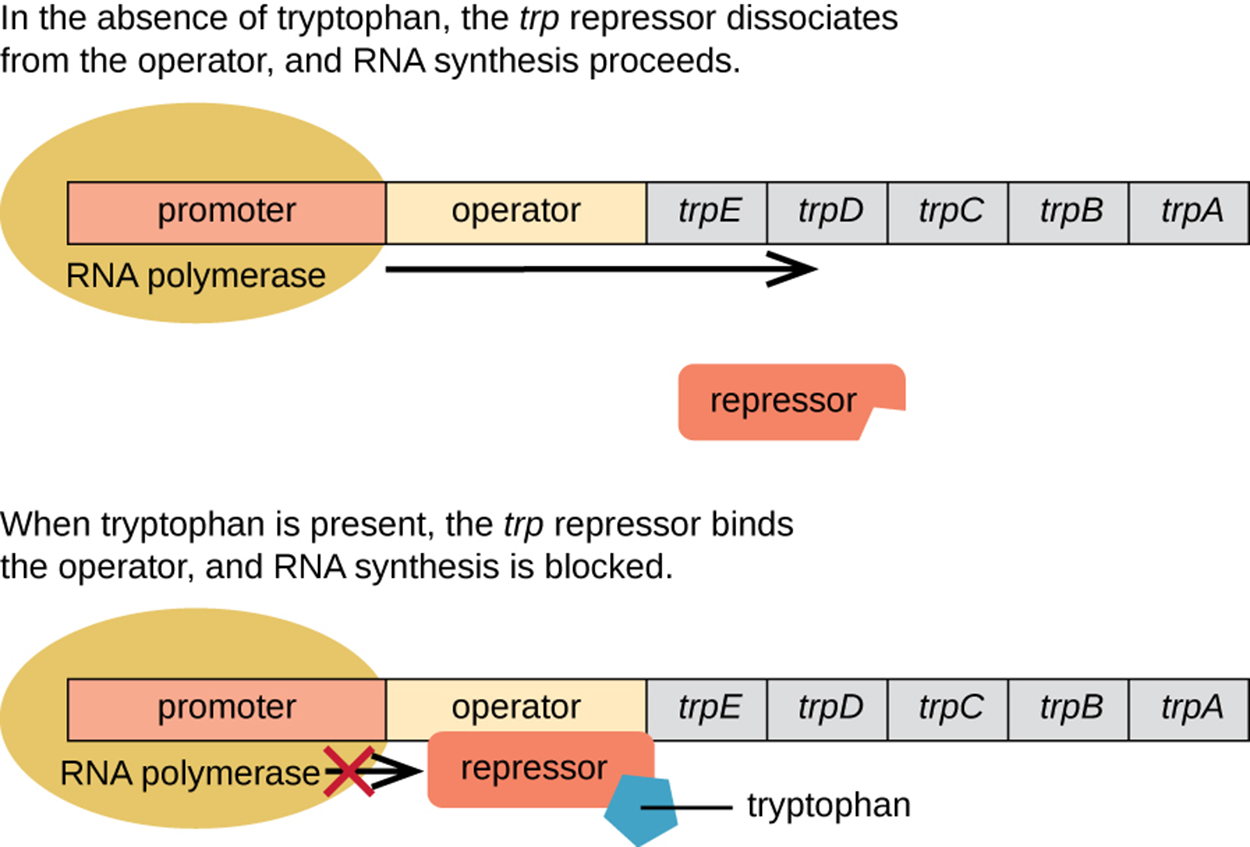

The lac operon is an example of an inducible operon and the trp operon is an example of a repressible operon. As shown in the image below, the default condition is for RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter and for transcription to occur. However, the enzymes produced by these genes produce tryptophan and an abundance of tryptophan indicates that there is no need to produce more enzymes right away. When two tryptophan molecules bind to the repressor, they cause the repressor to change shape so that it is active and can bind to the operator. This prevents further transcription unless tryptophan becomes low again.

Prokaryotes are capable of regulation at higher levels as well. These higher levels of regulation control multiple operons simultaneously.

Alarmones are small intracellular nucleotide derivatives that are produced in response to impending stress. They change patterns of gene expression and stimulate the expression of stress-response genes. It is thought that these are important in pathogenic bacteria as they respond to host defense mechanisms, making them important for understanding disease mechanisms and effects of different treatments.

Prokaryotes also are able to regulate genes at a higher level by using different σ factors. Because the σ subunit of RNA polymerase is important in binding to the promoter, using alternate σ factors can influence which genes are expressed. The σ factor recognizes sequences within a bacterial promoter, so different σ factors recognize slightly different promoters.

Although this lesson will not address them in detail, it is important to know that other methods of regulation exist. For example, another mechanism of regulation in prokaryotes is attenuation. In attenuation, structures formed by the RNA transcript as it is being produced influence whether transcription continues or stops. Riboswitches are small regions of noncoding RNA found within the 5′ end of some prokaryotic mRNA molecules. Riboswitches can bind to a small intracellular molecule to stabilize certain secondary structures of the mRNA molecule, determining which structure forms and therefore influencing whether transcription and translation continue.

This lesson has focused on prokaryotic regulation and on operons, but it is important to realize that many other types of regulation exist. Eukaryotes have a wide variety of regulatory mechanisms not addressed here.

Eukaryotic transcription can be controlled through the binding of transcription factors including repressors and activators. However, eukaryotic transcription can also be affected by the binding of proteins to distant regions of DNA called enhancers. The looping of DNA brings these distant regions closer so that they can interact with the promoter.

In eukaryotes, DNA-level control is very important. DNA molecules or associated histones can be chemically modified to influence transcription, and this is called epigenetic regulation. Methylation of certain cytosine nucleotides in DNA in response to environmental factors has been shown to influence the use of DNA for transcription, generally reducing gene expression. Chemical modifications and packaging can affect the availability of loosely wound DNA with promoters that RNA polymerase can access for transcription. Some of these epigenetic changes are heritable and this topic is an exciting area of current research.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.