Table of Contents |

A criminal justice system is an organization that exists to enforce a legal code. There are three branches of the U.S. criminal justice system: the police, the courts, and the corrections system.

Police are a civil agency in charge of enforcing laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level. No unified national police force exists in the United States, although there are federal law enforcement officers. Federal officers operate under specific government agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI); the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Federal officers can only deal with matters that are explicitly within the power of the federal government, and their field of expertise is usually narrow.

EXAMPLE

A county police officer may spend time responding to emergency calls, working at the local jail, or patrolling areas as needed, whereas a federal officer would be more likely to investigate suspects in firearms trafficking or provide security for government officials.State police have the authority to enforce statewide laws, including regulating traffic on highways. Local or county police, on the other hand, have a limited jurisdiction with authority only in the town or county in which they serve.

Social theorist Michel Foucault sees the police as agents of society who enforce the power structure. He wrote about the history of policing and imprisonment in his landmark book Discipline and Punish, which we will discuss further in the next lesson. Foucault explained that historically, crime was often punished with public torture and execution, which were only sometimes carried out after a process of a criminal investigation. Only the king (or other monarch) had the power to punish people, through his representatives (the court, the executioner), but this power imbalance was somewhat corrected through the public forum. When executions occurred in public, common people were shown the power of the king, but they could also turn against the king's decisions and choose to side with the accused, which was dangerous for the king.

EXAMPLE

Think of the French Revolution, in which public executions led to riots by the people against the government.When societies move to using a professionalized police force, Foucault says, it gives the law agency and heft and creates some degree of transparency. In theory, laws are now enforced by an impartial third party that is bound to an oath to uphold them. Punishment is no longer tied to a sovereign but to a public agency. State sponsored punishment no longer reflects poorly on individual government officials because it becomes depersonalized.

IN CONTEXT

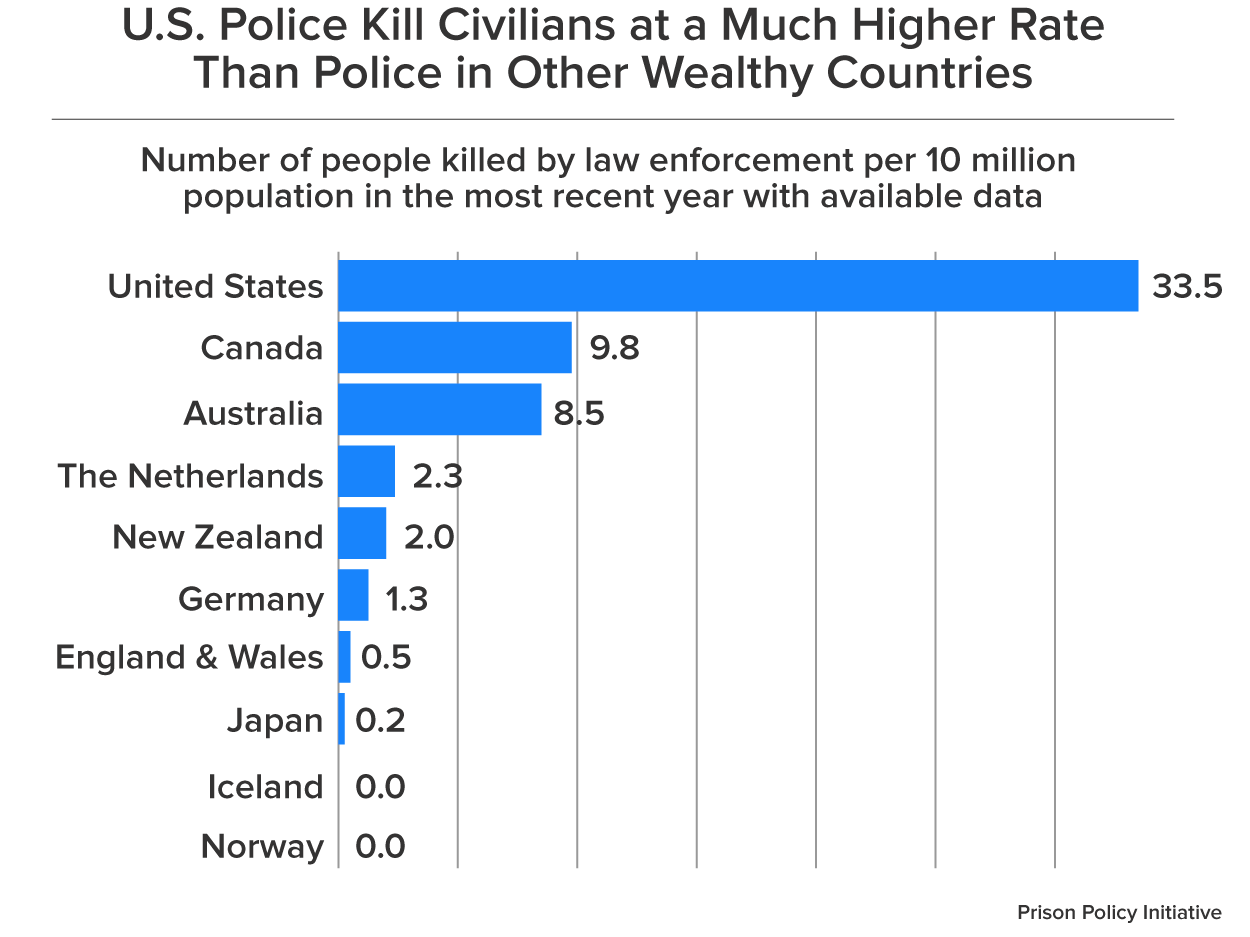

U.S. police forces have always been empowered to use lethal force against citizens in certain situations. Although an elaborate process of arrest, conviction, sentencing, and appeals is necessary before the government can execute a citizen for a crime, killings by police in the process of an arrest are a form of extrajudicial killing. This means that the killing happens outside the judicial process. In recent years, as smartphone cameras have become ubiquitous and have allowed bystanders to capture police killings on camera, more and more attention has been drawn to the problem of extrajudicial police killings and other extreme uses of force by police. One outcome of this heightened attention on police use of force is a movement calling for the defunding of police.

Police funds are public funds, and tax-payers have a right to input in how their money is spent by government agencies. Scrutiny of police budgets have found that civilian police departments across the country have been continually investing in military-style weapons and tactical gear since the 1990s, such as tanks. Despite falling violent crime rates, many police forces continue to arm themselves like they are approaching a war zone, rather than communities they are sworn to protect and serve. Some proponents of defunding the police believe that if police departments were given less money to spend, they wouldn't be able to acquire any more inappropriately militarized weapons.

Many supporters of current police practices have spread the idea that defunding the police would mean anarchy; they claim that defunding the police would mean that no one would come to help you if you were robbed or attacked, and that citizens would be on their own to solve problems. While there are certainly some activists who call for an abolishment of police departments altogether, most mainstream proponents of defunding the police don't seek to radically restructure society. Rather, they seek to restructure how society responds to emergencies.

Defunding the police is about a reallocation of police funding. The idea would be to take some of the pressure of non-criminal emergencies off of the police, and instead hire social workers and other, specialized emergency personnel, who would be trained to deal with specific types of emergencies such as mental health crises and welfare checks. For the times that police are actually the best responders to an emergency, proponents seek to provide training to police officers in de-escalation methods and other non-lethal ways of apprehending suspects.

There have already been some successes with similar reform methods. In 2020, following a years-long effort to re-train police in different methodologies, not one Newark, NJ police officer fired a shot during the entire year.

Though all societies make this eventual move to professionalized police agencies, it looks very different in different societies. In the U.S., there are many different police jurisdictions and levels of police, from local to state to federal to tribal, all operating independently from one another. In most other Western nations, the police are all overseen by a national police agency or report up to an umbrella national agency. When it comes to training and policies, many researchers see benefits to a national police agency. Supporters of decentralized policing say that it allows for individual communities to choose the type of policing that works for them.

Once a crime has been committed and a violator has been identified by the police, the case goes to court. A court is a system that has the authority to make decisions based on law. The U.S. judicial system is divided into federal courts and state courts. As the name implies, federal courts (including the U.S. Supreme Court) deal with federal matters, including trade disputes, military justice, and government lawsuits. Judges who preside over federal courts are selected by the president with the consent of Congress.

State courts vary in their structure but generally include three levels: trial courts, appellate courts, and state supreme courts. In contrast to the large courtroom trials in TV shows, most noncriminal cases are decided by a judge without a jury present. Traffic court and small claims court are both types of trial courts that handle specific civil matters.

Criminal cases are heard by trial courts with general jurisdictions. Usually, a judge and jury are both present. It is the jury’s responsibility to determine guilt and the judge’s responsibility to determine the penalty, though in some states the jury may also decide the penalty. Unless a defendant is found “not guilty,” any member of the prosecution or defense (whichever is the losing side) can appeal the case to a higher court. In some states, the case then goes to a special appellate court; in others it goes to the highest state court, often known as the state supreme court.

The corrections system, more commonly known as the prison system, is charged with supervising individuals who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offense. As of 2016, The United States holds more than 2.3 million people in prisons and jails, the highest share of the population of any country in the world. The 2.3 million people incarcerated in the United States represent almost a quarter of all the incarcerated people in the world, although the United States in general only accounts for 5% of the world's population.

However, a great many people are also held in jails without a conviction, often due to an inability to pay bail. When someone is arrested, they are meant to be released until their trial, as long as they aren't extremely dangerous to the community or likely to run away. Usually, a judge sets an amount of money that the suspect needs to pay the court as a sort of ransom, in order to guarantee that they return for their trial. Bail can sometimes be a lot of money, and many people can't afford to pay and don't have friends or family who can pay for them.

At any given time, there may be as many as half a million people imprisoned in the United States who have not been convicted of any crime but who have been unable to pay bail. There are also more than 40,000 people held in immigration detention, many of whom have committed no crime other than living in the United States without current authorization.

Prison is different from jail. A jail provides temporary confinement, usually while an individual awaits trial or parole. Prisons are facilities built for individuals serving sentences of more than a year. Whereas jails are small and local, prisons are large and run by either the state or the federal government, or by a private, for-profit company.

Parole refers to a temporary release from prison or jail that requires supervision and the consent of officials. Parole is different from probation, which is supervised time used as an alternative to prison. Probation and parole can both follow a period of incarceration in prison, especially if the prison sentence is shortened.

Most sociological thought on crime and punishment revolves around the functions of the criminal justice system. A criminal justice system may be designed to deliver on one or multiple of several basic functions:

EXAMPLE

Of the 195 countries in the world that are recognized by the United Nations, fifty-four still practice capital punishment. One hundred and seven countries have abolished capital punishment by law, while seven retain it for war crimes and twenty-seven countries have not executed anyone in a long time although their laws are not specifically abolitionist.EXAMPLE

The United States has an extremely high rate of recidivism, with more than 50% of people released from prison ending up incarcerated again. By contrast, Norway's prison system is focused on rehabilitation, with efforts made throughout a prisoner's sentence to reintegrate them into society. Norway has an extremely low rate of recidivism, around 20%.In 1975, the French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote Discipline and Punish, a highly influential book about criminal punishment and surveillance. In this book, he traces the history of punishment from public torture and executions to modern systems of incarceration.

One might think that a criminal justice system that relies on torturing the accused until they confess and then executing them in public spectacle is chaotic and illogical. But Foucault established a clear reasoning behind this system of punishment. In early modern Europe, after the medieval period but before the Enlightenment, state power was conceptualized as flowing from the king. Crime, therefore, was conceived as public actions against the king, and thus the king had to punish criminals in a visible way, through public executions enacted by the king's representatives (the executioners). This was also a time period in which common people held no property other than their own bodies, so physical pain was the obvious way in which to take something away from an accused or convicted criminal.

Torture, Foucault argued, justified itself through confession. If a man confessed to a crime under torture, it legitimized both the torture that led to the confession, and also the further punishment (such as execution) that followed the confession. It also created something of a playing field, if not a level one, between the king and the accused as individuals. When an accused person managed to survive torture without confessing to a crime, it was a successful challenge to the king's authority.

In the 18th century, reforms led to the abandonment of physical torture and public execution in favor of workhouses, or factory prisons. Foucault argues that societies did not stop torturing people because they became more humane and enlightened. He says that the change occurred because power had shifted away from the king and the nobility to the middle classes, which formed out of mercantilism and professional careers. Crime came to be conceived of as acting against property, rather than against the king.

At the same time, the idea that common people owned only their bodies gave way to the idea that bodies are valuable due to the labor they produce. Aside from any claims of humanity and morality, it was also practical for the mercantile middle classes to punish those who committed crimes against property not through physical pain on their bodies, but by using their bodies' capacity for labor. It also became practical for the middle classes to want a more elaborate system of accusation, trial, and defense, because this created middle class jobs (as lawyers, judges, and other roles) and created a system that seemed like it applied to everyone equally but that could actually be circumvented with money. The shift to workhouse imprisonment over torture and execution, Foucault says, was a practical shift that reflected changes in the European political and economic structure in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Another major shift in systems of punishment identified by Foucault related to surveillance. He writes about the idea of the panopticon, which was a type of prison architecture proposed by English theorist Jeremy Bentham in 1791. Bentham proposed a prison design that allowed a single security guard to monitor a large number of prisoners at once, through constructing cells around a central viewing tower. The crucial piece of Bentham's design is that the prisoners wouldn't be able to tell whether the guard was observing them at any given moment, but it was always possible that the guard was observing them. This would force the prisoners to always assume they were being watched, and thus to police their own behavior and follow the rules at all times.

When Foucault wrote about the panopticon, it was as a metaphor for the impact of state surveillance on a society. He described how the idea of surveillance as a means of discipline—of making people behave in the way that is desired by the people with power—permeates society through surveillance structures not just in prisons, but also in hospitals, schools, and workplaces. Enforcement of norms then becomes pervasive and internalized, as people police their own behavior.

This concept was also vividly described in George Orwell's classic novel about a surveillance state, 1984: “There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment ... you had to live ... in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised.”

Functionalists would look at the police as agents who enforce social norms that are codified into law. Durkheim saw great use for systems of punishment in reinforcing and reflecting society’s “collective conscience” and what a society puts forth as its ideal.

Conflict theorists view the police as a force of the government that unfairly targets low income and minority people to maintain an unfair system. Rusche and Kirshheimer (1939/1968) took note of the fact that punishments in the United States changed from physical torture to physical labor as the needs of the economy changed at the end of slavery in the United States. They noted that convicts were cheap, available labor at the moment when slave labor became otherwise abolished. Because the 13th Amendment prohibited slavery except as punishment for a crime, convict labor was used to produce even higher profits for those in economic power in the society. Punishment could also be used to control lower class populations during times of high unemployment.

Symbolic interactionists would apply labeling theory as an explanation of the power of shame to maintain a society’s norms. All people get clues from their environment and the interactions with people around them. The ceremony around crime and punishment from a trial to a conviction, incarceration or execution is how we give meaning to those actions within the scope of a state sanctioned system.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) "INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY" BY LUMEN LEARNING. ACCESS FOR FREE AT LUMEN LEARNING. (2) "INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY 2E" BY OPENSTAX. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX. LICENSE (1 & 2) CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.