Table of Contents |

Flexibility is the ability of a joint to move through its full range of motion. We use flexibility throughout our everyday activities, such as reaching for an item on a high shelf, bending down to put on our shoes, or standing up to get out of a chair. If joints are restricted in their full range of motion, these activities can become difficult if not impossible.

EXAMPLE

The normal range of motion at the shoulder joint is 180 degrees. If muscles surrounding the shoulder are tight and inflexible, the range will be restricted. A lower range of motion can inhibit normal movements, like being able to reach overhead.One way to define mobility is the ability to move freely in changing and controlling body position (Ernstmeyer & Christman, 2021). Mobility requires not just flexibility, but also strength, coordination, and body awareness (Starrett & Cordoza, 2015). When we consider the common body positions of everyday life activities, such as pushing, pulling, stepping, and squatting, mobility can give us a greater picture of a person’s overall movement function.

EXAMPLE

The sit-and-reach test is a common test to assess flexibility of the hamstrings and lower back. (You’ll learn more about this test in the next lesson). However, scoring well on the sit-and-reach does not necessarily mean that a person has good total body mobility.IN CONTEXT

In the human body, about half of our major joints favor mobility with being able to move freely and uninhibited. The other half of the joints favor stability, the ability to maintain or control joint movement or position (American Council on Exercise, 2020). In fact, your body is essentially a stability-mobility sandwich, designed in a way that a more mobile joint can receive support from the stable joints above and below it.

To imagine this “stability-mobility sandwich” in action, think about performing any type of squatting movement, such as rising out of a chair, bending to pick up an object, or squatting with weights at the gym. Your hip joints favor mobility, and that mobility partially dictates how deeply you can squat while keeping an upright posture. Meanwhile, your knee joints favor stability, helping you keep your body balanced over your feet. Your ankle joints favor mobility, so ankle mobility allows you to squat deeply while keeping both feet fully on the floor.

Stability does not mean that the joint shouldn’t move at all. Rather, it means that the most effective movement depends on the joint providing more support than a large range of mobility. Consider the knees in our squatting example. Your knees need to bend and straighten to do movements of everyday life. However, they can only bend and straighten primarily, rather than moving side to side or rotating freely. If all the joints in the lower body favored mobility, squatting would likely feel quite wobbly and imbalanced since some joints would lack support from stability.

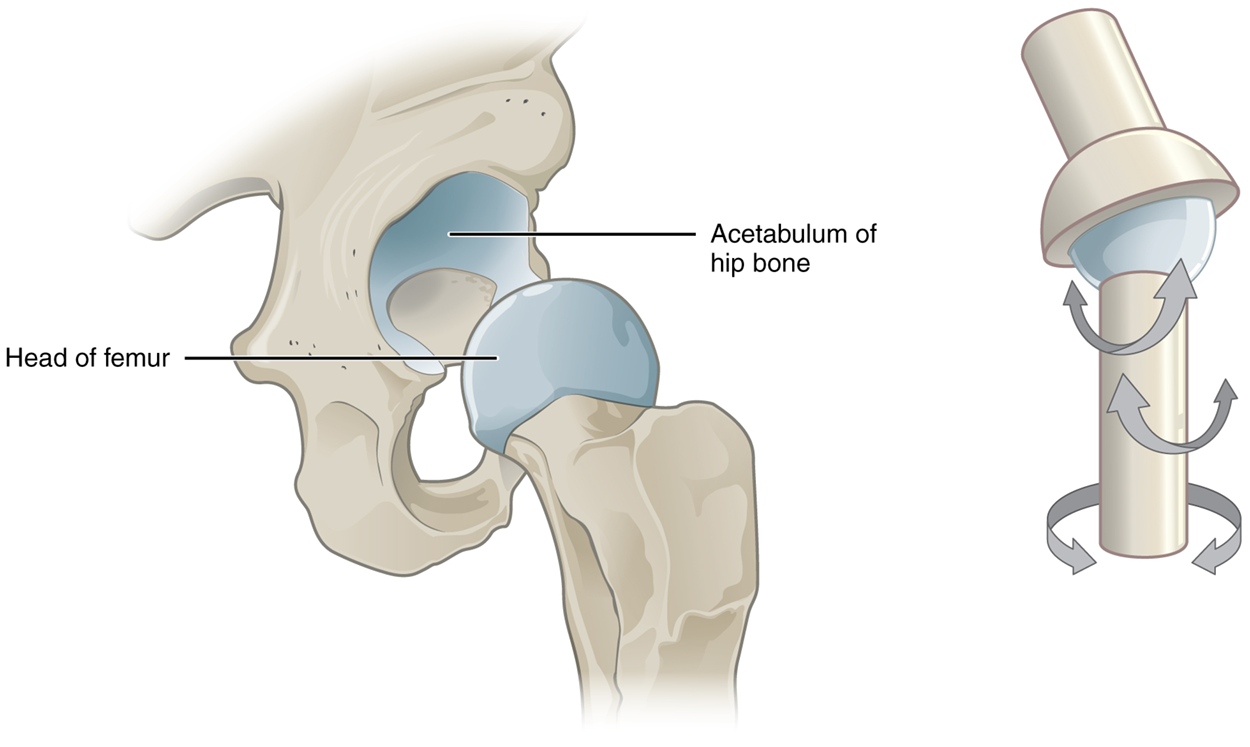

The squatting example above illustrates one factor that affects flexibility and mobility, which is the type of joint structure. The major joints in your body can be divided into three types based on their axis of motion and the type of movement they allow (Haff & Triplett, 2016):

Another factor affecting flexibility and mobility is soft tissue restriction. Soft tissue can include muscles, body fat, and tendons.

EXAMPLE

A person with a very muscular upper body may have trouble scratching their back because their muscle mass gets in the way. Or, a pregnant woman or a person with a high amount of abdominal fat mass may have trouble touching their toes because their stomach gets in the way.Age and sex also play a role in flexibility and mobility. In general, females tend to be more flexible than males, partly because females typically have greater muscle elasticity (Yu et al., 2022). Older adults tend to be less flexible than younger adults; some reasons for this include lower physical activity (Yu et al., 2022) and age-related diseases or conditions that can make full ranges of motion painful or fatiguing, such as arthritis (Ernstmeyer & Christman, 2021).

Lastly, your activity and lifestyle can affect flexibility and mobility, whether for better or worse. You’ve learned that the body adapts to the demands placed upon it. Putting the body in repetitive positions, such as sitting for long periods with a sedentary lifestyle, can cause muscles to contract and shorten since they are not being used (Hayward & Gibson, 2014). Conversely, staying active in a variety of ways can help the body maintain full ranges of motion at all major joints.

IN CONTEXT

Genetic conditions can also affect flexibility and mobility by causing hypermobility in the body, where joints easily move beyond normal ranges of motion. Hypermobility becomes problematic when it causes the joints to lack proper stability and control, which can then cause pain and increased risk of injury (Clapp et al., 2021).

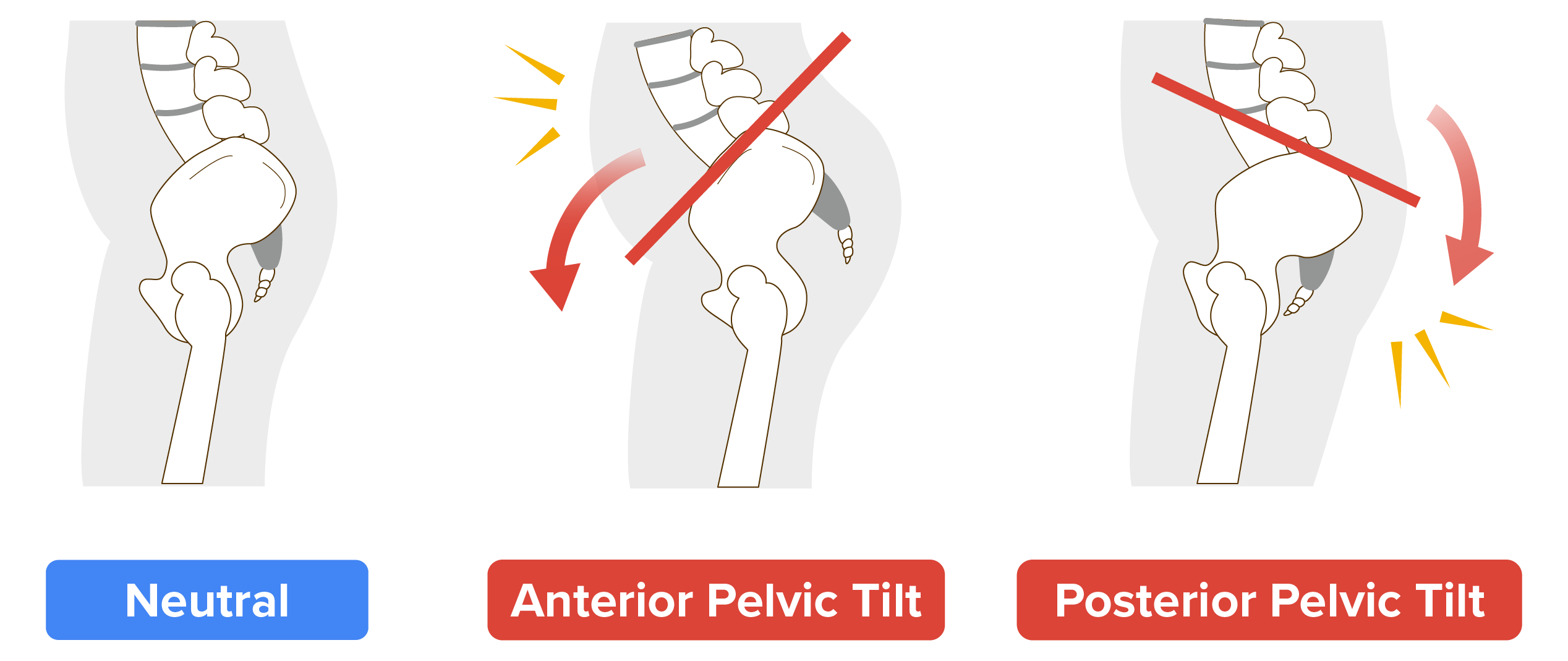

In our conversation about flexibility, mobility, and stability over this lesson, back health is an important component, especially since back pain is a common issue in the population. When the normal “stability-mobility sandwich” of the body is disrupted, compensation can occur which leads to pain or stiffness. Sitting for long periods, being inactive, moving with poor posture, and other factors can tilt the pelvis out of alignment, whether forward or backward. As a result, the stability-mobility sandwich of the muscles that act on the pelvis can become altered.

Low back pain can have many other causes, such as muscle strains, damage to the discs, or arthritis, just to name a few. If you are experiencing low back pain, seeking help from a health professional should be your first step. However, exercises that promote stability and mobility of the spine can help restore the balance of the stability-mobility sandwich of the body.

When considering the spine as part of the body’s stability-mobility sandwich, the lumbar spine, or lower back, favors stability, and the thoracic spine, or mid-back, favors mobility. Spinal stability exercises help to reinforce good movement patterns without putting extra load on the spine (McGill, 2006).

EXAMPLE

The bird dog, or quadruped, is a spinal stability exercise. The body position for the bird dog starts on all fours, with hands under the shoulders and knees under the hips. A person can start by extending and raising one leg, holding the leg parallel to the floor without any motion in the spine and without the pelvis tilting to one side (McGill, 2006). If this feels stable, the movement can progress to extending and raising the opposite arm and holding this body position for 6–8 seconds before switching sides. This exercise can also be done while standing and using a chair or wall for balance if being on all fours is painful or uncomfortable.

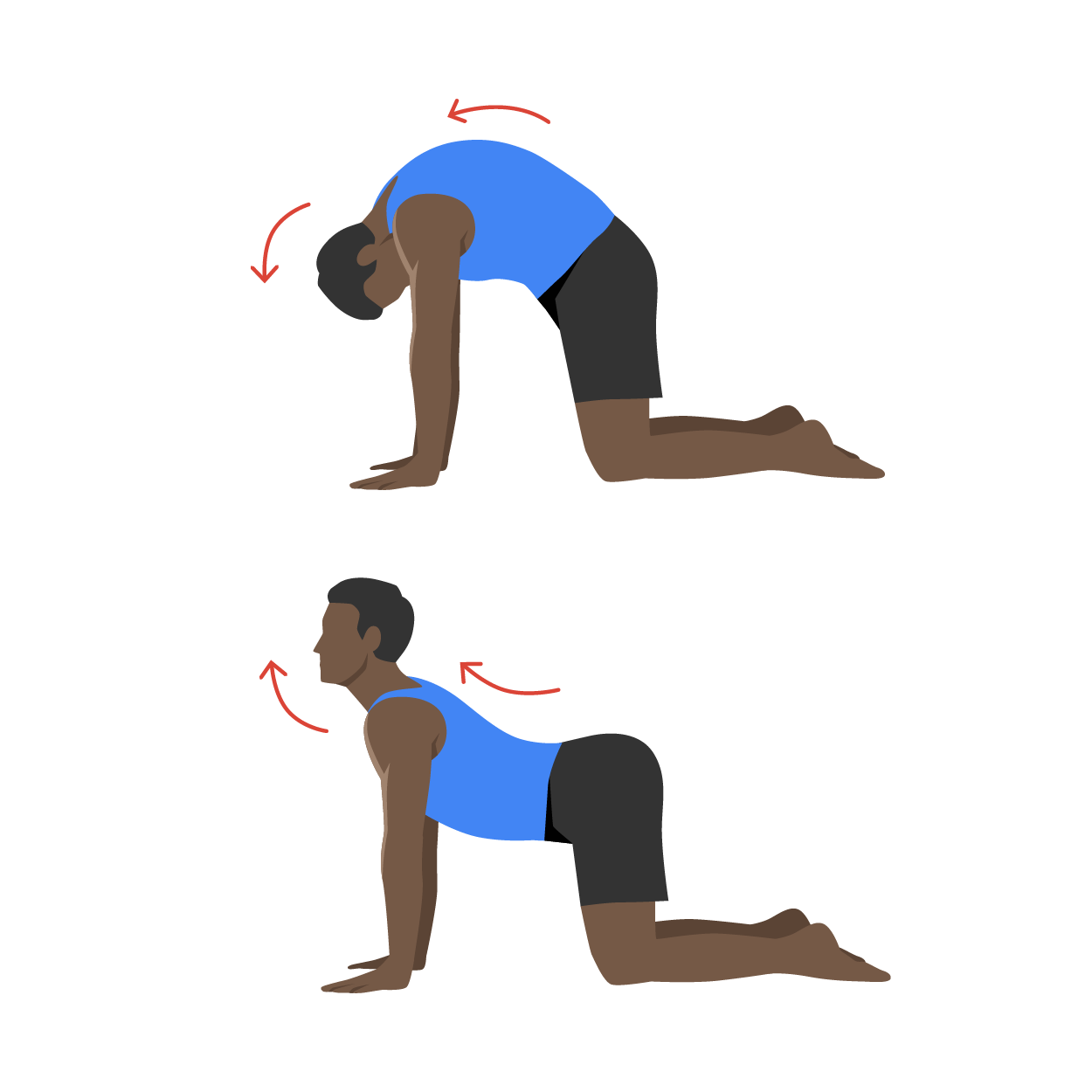

Spinal mobility exercises take the spine slowly through full ranges of motion, such as flexing and extending the spine (McGill, 2006).

EXAMPLE

The cat-camel, which is sometimes called cat-cow, is a spinal mobility exercise. This movement takes all regions of the spine through flexion and extension (McGill, 2006). The body position for the cat-camel also starts on all fours, with hands under the shoulders and knees under the hips. In the upward (cat) phase, exhale to gently round the spine upwards toward the ceiling, with the head falling toward the chest. Inhale to slowly let the back drop into an arch with the stomach toward the floor and the shoulder blades drawing together. This exercise can also be done while seated in a chair if being on all fours is painful or uncomfortable.

Doing flexibility exercises regularly is recommended by national health and exercise organizations. The American College of Sports Medicine provides the following guidelines per the FITT principle (Liguori, 2021):

Doing flexibility exercises 2–3 times a week for 3–4 weeks can improve the range of motion, along with improving postural stability and balance (Garber et al., 2011). Flexibility can also promote a sense of physical and mental relaxation (American Council on Exercise, 2022).

However, research is mixed on the benefits of improving flexibility. While flexibility is one of the five components of health-related fitness, it is the only component that is not associated with living longer or aging better (Nuzzo, 2020). Some research indicates that performing flexibility exercises provides benefits like preventing injuries, reducing pain, and improving performance (Matthews, 2017).

IN CONTEXT

One way that improving flexibility can impact performance is by improving the ability to apply force through a greater range of motion (Haff & Triplett, 2016). For example, picture a tennis player about to serve the ball. A tennis player with a full range of motion at the shoulder can apply force over a longer time period than a tennis player with a limited range of motion.

However, other research reflects that doing regular flexibility exercises does not have any association with reducing injuries, preventing pain, or performing better in sports (Nuzzo, 2020). Stretching is difficult to study on an individual level, so it is still a valid part of an exercise program if it makes you feel good and seems to have benefits.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY Anna Caggiano FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE. Markup: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY Anna Caggiano FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.

REFERENCES

American Council on Exercise (2020). The exercise professional’s guide to personal training: A client-centered approach to inspire active lifestyles. Jo, S., Bryant, C.X., Dalleck, L.C., Gagliardi, C.S., and Green, D.J. (eds). ISBN: 9781890720766

American Council on Exercise (2022). Benefits of flexibility. American Council on Exercise. www.acefitness.org/resources/everyone/blog/6646/benefits-of-flexibility/

Clapp, I. M., Paul, K. M., Beck, E. C., & Nho, S. J. (2021). Hypermobile disorders and their effects on the hip joint. Frontiers in Surgery, 8, 596971. doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.596971

Ernstmeyer, K., Christman, E., eds. (2021). Nursing Fundamentals: Chapter 13, Mobility. Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN). Eau Claire (WI): Chippewa Valley Technical College. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591828/

Garber, C. E., Blissmer, B., Deschenes, M. R., Franklin, B. A., Lamonte, M. J., Lee, I. M., ... & Swain, D. P. (2011). Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(7), 1334-1359. doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (4th ed). National Strength and Conditioning Association. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics.

Hayward, V.H., & Gibson, A.L. (2014). Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription. Illinois: Human Kinetics. ISBN: 9781450466004

Liguori, G. (2021). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. American College of Sports Medicine. ISBN: 9781975150181

Matthews, J. (2017). 10 reasons why you should be stretching. American Council on Exercise. www.acefitness.org/resources/pros/expert-articles/6387/10-reasons-why-you-should-be-stretching/

McGill, S. (2006). Ultimate back fitness and performance, 3rd ed. Backfitpro, Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. ISBN: 0973501804.

Nuzzo J. L. (2020). The case for retiring flexibility as a major component of physical fitness. Sports Medicine, 50(5), 853–870. doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01248-w

Starrett, K., & Cordoza, G. (2015). Becoming a supple leopard: the ultimate guide to resolving pain, preventing injury, and optimizing athletic performance, 2nd ed. Las Vegas, Victory Belt Publishing Inc.

Yu, S., Lin, L., Liang, H., Lin, M., Deng, W., Zhan, X., Fu, X., & Liu, C. (2022). Gender difference in effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on flexibility and stiffness of hamstring muscle. Frontiers in physiology, 13, 918176. doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.918176