Table of Contents |

To begin with, recall the nature of an argument. If you want to make an argument, then you want someone to agree with something. To do that, you must give them a reason to agree with you. In other words, you must give some support for whatever it is that you want someone to accept. What does the supporting are called the premises, and what is supported by the premises is called the conclusion.

The premises are statements that claim to say something true of the world. This is called a factual claim. The way you get from the factual claim to the conclusion is by saying that the conclusion follows from the supposed facts you provide.

IN CONTEXT

Imagine you want to convince your teacher you didn’t skip school. The statement “I didn’t skip school” is the conclusion that you need to support in order for it to be accepted as true. You thus need some premises to do the supporting.

For instance, you might make the factual claim “I was at the doctor’s.” Assuming that the truth of this premise can be established (e.g., by a doctor’s note), then the conclusion “I didn’t skip school” is supported by the premise “I was at the doctor’s.”

In this context, the claim that the premises do support the conclusion is called the inferential claim.

In order to see if an argument works or not, you need to be able to distinguish the premises from the conclusion—that is, you need to separate out which part of the argument is intended to do the supporting, and which part is intended to be supported.

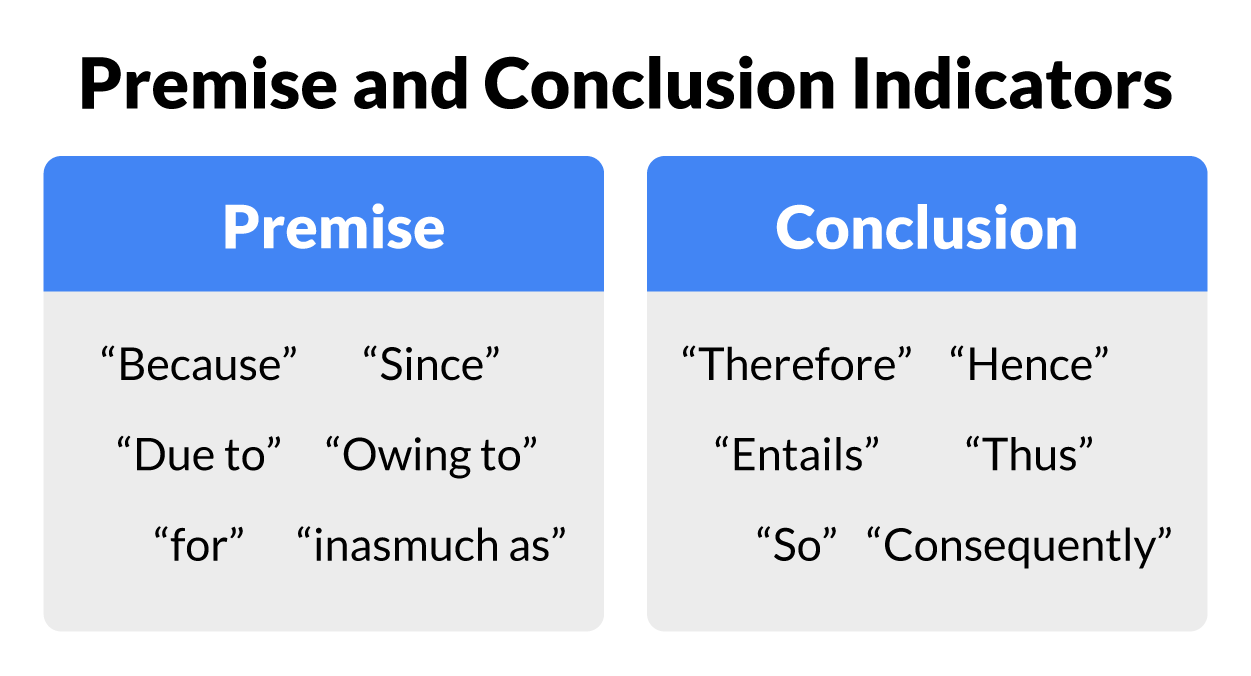

Often you can do this by looking out for certain words that indicate whether someone is offering a premise or a conclusion. Below are a few examples.

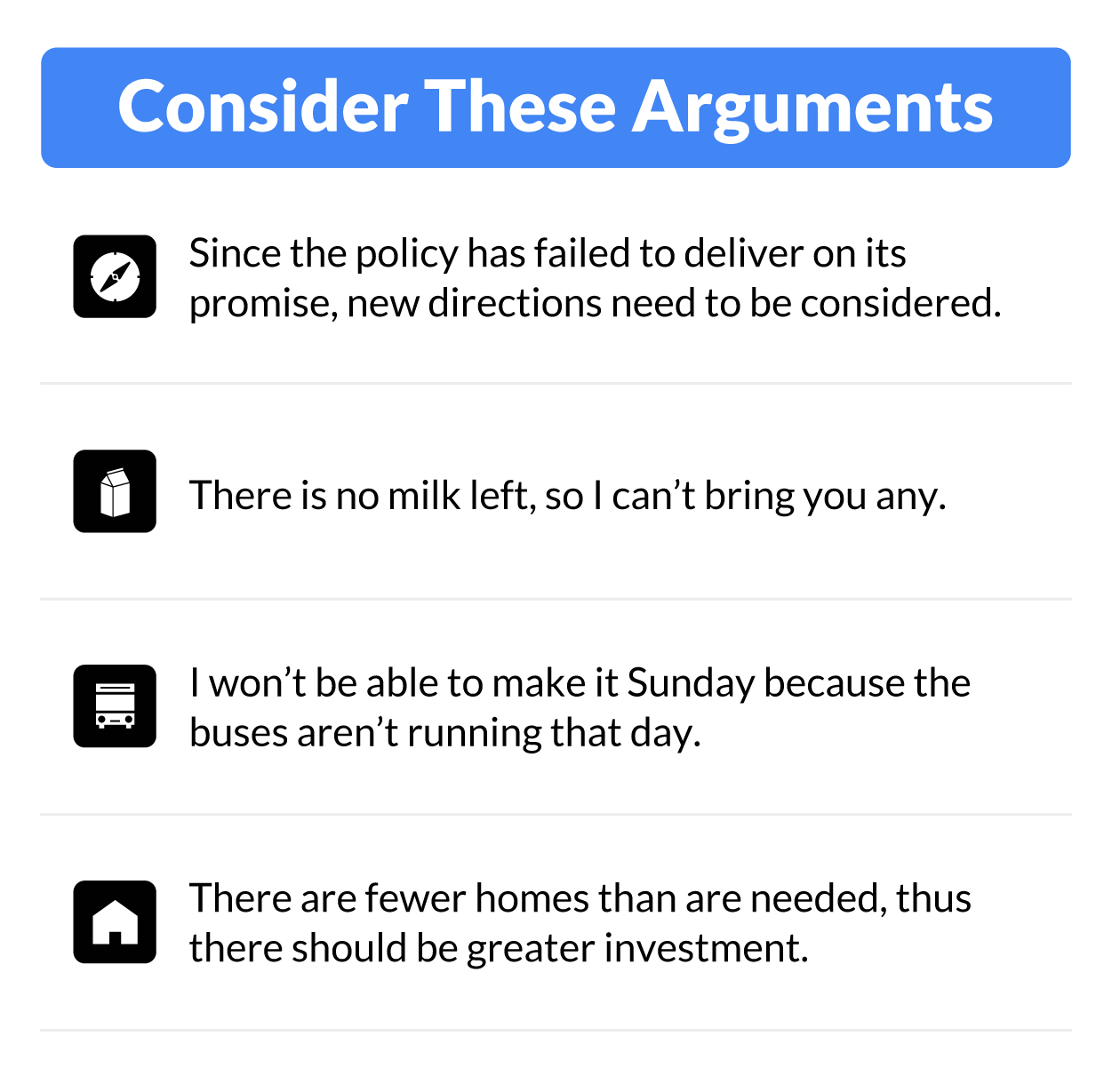

Let’s go through them to see which indicators were used. Click each one to see more.

Let’s go through them to see which indicators were used. Click each one to see more.