Table of Contents |

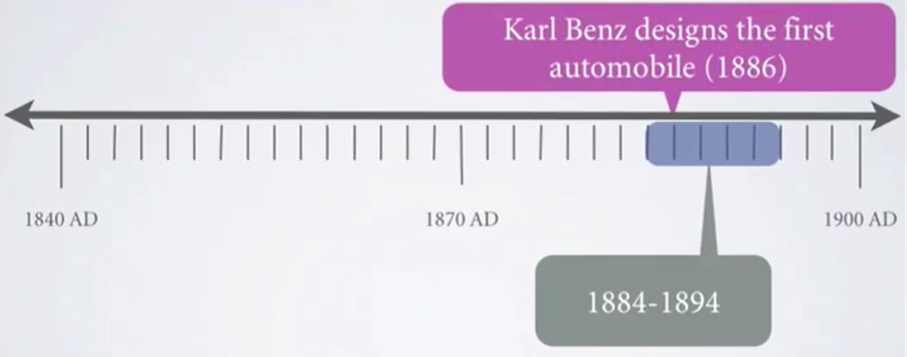

The artwork that you will be looking at today dates from between 1884 and 1894 and focuses geographically on Paris, France. It’s important to point out that Post-Impressionism, as more of a chronological reference than a specific style, literally means “after impressionism.” However, aside from the literal meaning, Post-Impressionism also refers to the spirit of the style rather than a specific time period. In other words, some Post-Impressionists were painting at the same time as Impressionists.

Post-Impressionism developed out of the belief many artists had that Impressionism had essentially run its course—that it couldn’t be taken any further—and they had grown weary from an overall lack of structure and focus on trivial subject matter, such as fleeting moments. Impressionism lingered into the early 20th century alongside Post-Impressionism.

Post-Impressionism was a different approach to painting and as a stylistic movement, it emphasized experimentation, such as in the type of brushstroke used, color experimentation, the distortion of form, and—in the case of Paul Cezanne—the existence of an underlying geometry. In many ways, it moved beyond the sketchiness of Impressionism and incorporated a bit more structure while retaining many of the painterly aspects of Impressionism. This, however, can make the distinction between Impressionism and Post-Impressionism a little difficult for the art history novice.

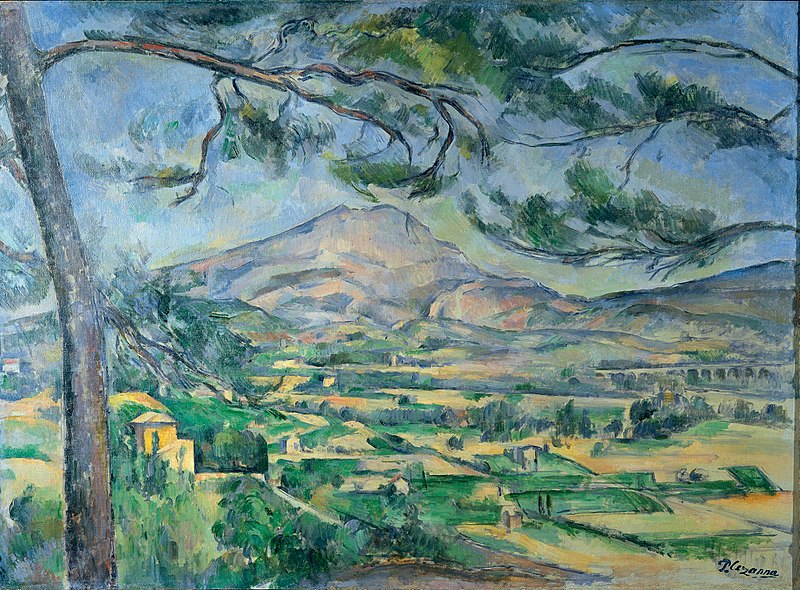

Paul Cezanne is an important painter, not only for his contributions to Post-Impressionism, but for serving as a bridge of sorts between the art of the 19th and 20th centuries—specifically bridging Impressionism with the modern art movements of the early 20th century.

Cezanne sought to make something solid out of Impressionism, articulating space and volume through color and geometric forms, which is what makes Cezanne’s work so recognizable. You can start to see these repeated patches of square color applied to more traditional forms of painting, such as the landscape shown below or the still life. Cezanne also gives this a sense of three-dimensionality with the use of atmospheric perspective.

1887

Oil on canvas

In this example of a still life with a basket of apples, notice how the space and volume of the painting are articulated through color rather than through shadow. It’s an analytic approach to painting that makes his artwork appear, to some, as more experimental than emotional.

1890-1894

Oil on canvas

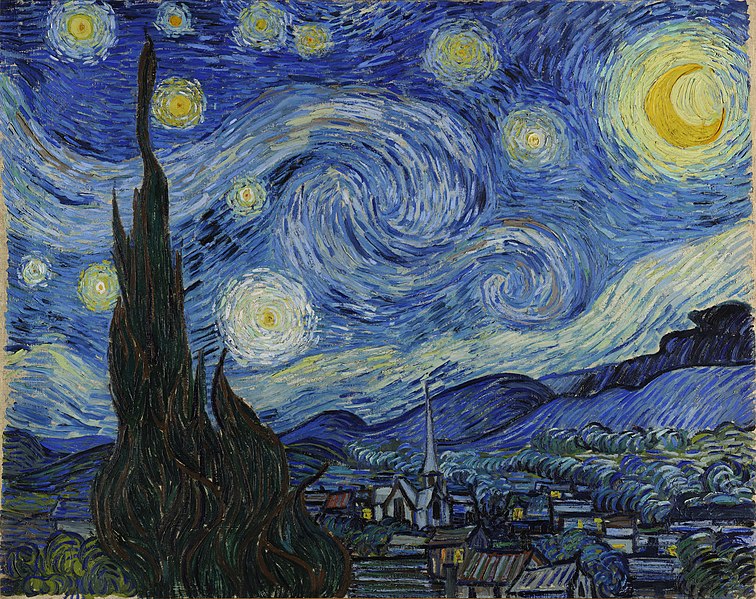

In contrast, the Post-Impressionist work of Vincent Van Gogh has more of the emotional closely attributed to it.

In reality, Van Gogh’s life is a fascinating and tragic look at the effects of mental illness on an individual and the emotional turmoil that results, articulated through his work. Below is one of his most famous pieces, “Starry Night.”

Van Gogh uses impasto, which is the buildup of paint on a surface to create a tactile effect. He uses color and form to create an expressive and emotional piece of art. Notice how the serenity of the evening is lost in the frenetic activity and vibration of the sky. It’s a personal interpretation by Van Gogh of a realistic scene, an interpretation that may have mirrored the internal frenzy of his own mind. It’s also an early example of Expressionist art that undoubtedly influenced later artists of the 20th century.

Pointillism was a form of experimental art developed in part by Georges Seurat. It was an exercise in color theory as much as it was a new way to paint. Pointillism is, in many ways, a precursor to modern pixels and how they are assembled to form a picture.

EXAMPLE

For example, look at this image of Mount Hood. From a distance, the image appears completely cohesive and realistic.

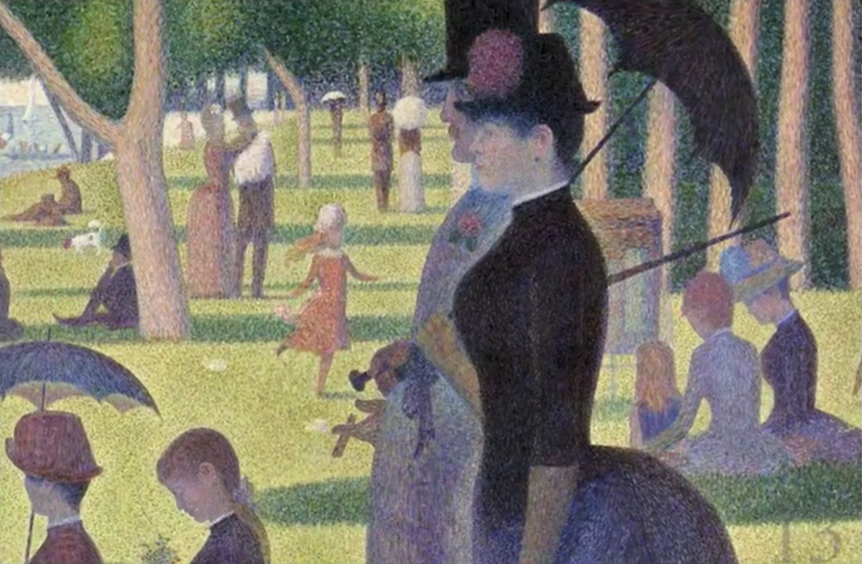

Pointillism is essentially the same idea, except that the dots are applied painstakingly by hand. In this method, as opposed to mixing colors, the artist relies on distance and the light color of the canvas showing through to help blend the colors together. It’s an effective method and creates a unique look. Colors tend to pop a bit more, which may have to do with the fact that the canvas is actually visible between the dots, similar to the visual effect of color television static.

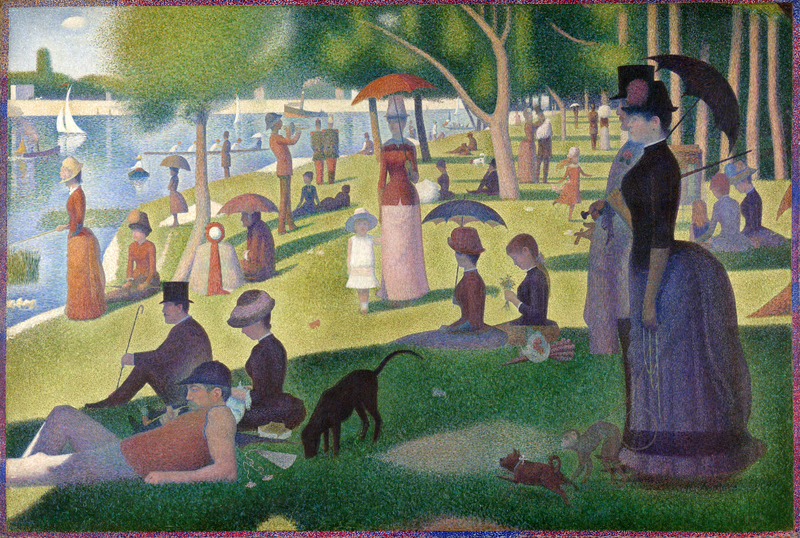

The painting below, sometimes referred to colloquially as “Sunday in the Park,” is an enormous canvas held at the Art Institute in Chicago. Its size is rather impressive; it literally takes up an entire wall.

1884-1886

Oil on canvas

As shown below, it’s helpful to see paintings such as this up close to truly appreciate the effect.

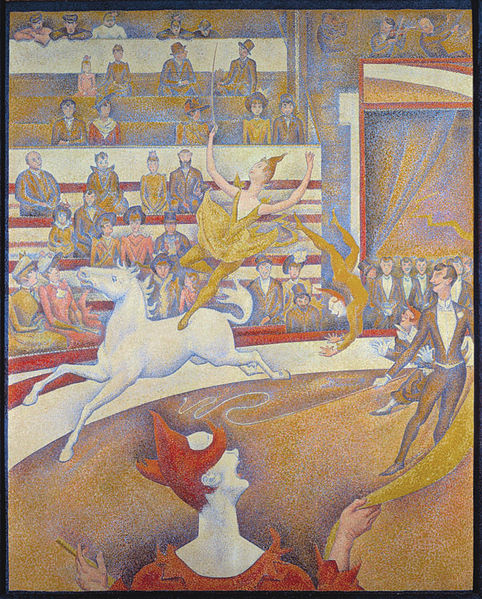

Seurat died quite young, around the age of 31. His final painting, which was incomplete at the time of his death, shows how refined his technique had become in such a short period of time. As you can see below, of particular note is how he’s capable of depicting shadow, as shown on the horse. Each dot of color stands alone in a pointillist painting, meaning there was very little margin for error.

1891

Oil on canvas

One of the most unifying attributes of Post-Impressionism is the idea of experimentation. This final image shows just how varied the art of Post-Impressionism was.

The flatness of the image and interesting use of contour lines is drastically different from Seurat’s work, for example, but shares a vision common to all Post-Impressionist artists, which is to take the concept of what art could be and move it in bold new directions.

_1892.jpg)

1892

Chromolithograph (print)

Source: This work is adapted from Sophia author Ian McConnell.