Table of Contents |

We defined politics in the previous tutorial as the ability to win and wield power to affect organizational decisions, particularly in times of uncertainty or disagreement. If there is no disagreement, there is no need for political activity. Once again, although the term has an air of scheming and duplicity, not all politics in an organization are dysfunctional or bad. Many managers use their political influence on behalf of their departments, or for the organization as a whole.

Large organizations are highly political entities. However, the intensity of political behavior varies, depending upon two key factors.

The first is the presence of established policies, procedures, and objective criteria that make processes fair and consistent. An example is personnel decisions like hiring and firing, promoting, or disciplining staff. These are very vulnerable to political behavior if there are no policies in place or if policies are vague. They are more immune to political behavior if the process is highly structured and codified by policy. Simply put, political behavior is more common when there is high uncertainty.

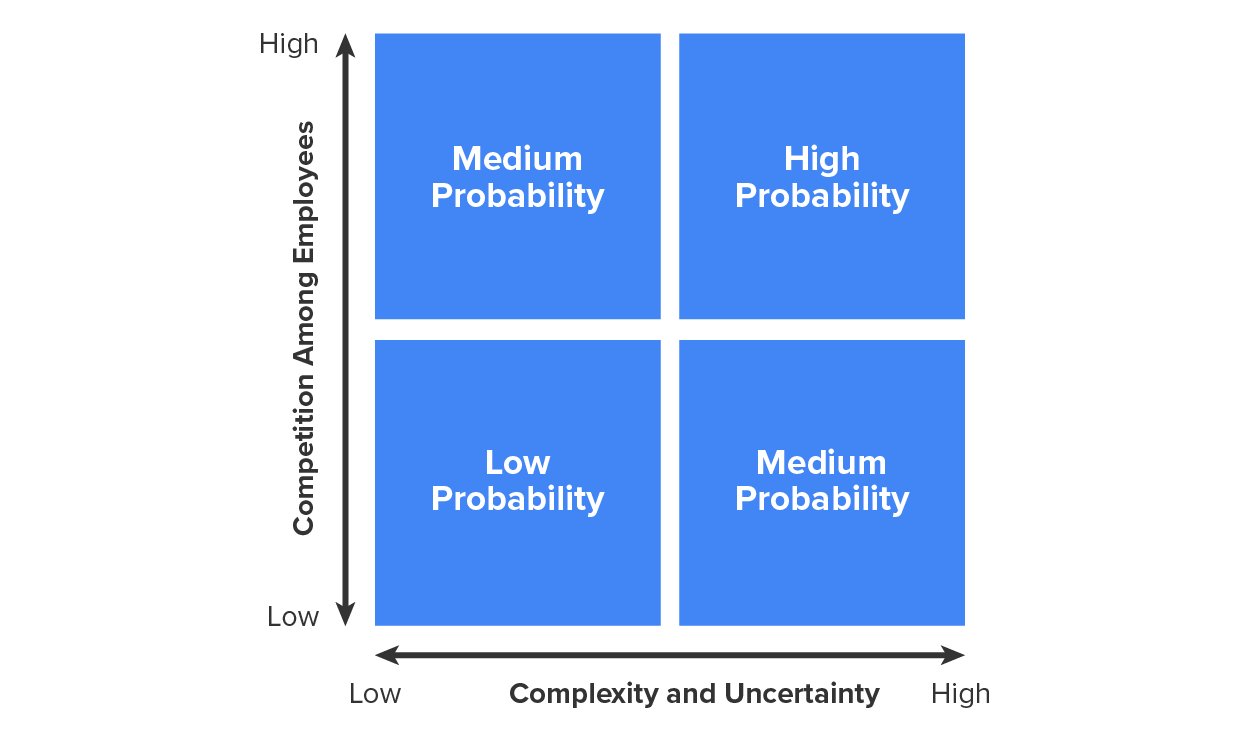

The other factor is competition among employees, such as organizations where promotional opportunities are rare and the field of contenders is large, such as a law firm with many associates and infrequent opportunities to become a partner. Many organizations have competition for resources: staff, discretionary budgets, space, and interest from organizational leaders. From this you can see that political behavior is highest when there is a high level of competition and uncertainty, and lowest when there is less competition and less uncertainty.

Following the above model, we can identify conditions conducive to political behavior in organizations.

| Conditions | Description | Political Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous Goals | When the goals of a department or organization are ambiguous, more room is available for politics. | People or groups will try to define goals to their advantage. |

| Limited Resources | Politics surface when resources are scarce and allocation decisions must be made. If resources were ample, there would be no need to use politics to claim one’s “share.” | People or groups try to maximize their own access to resources. |

| Changing Technology and Environment | Political behavior is increased during times of change to the organizational environment since changes bring uncertainty. | People try to guide change to maintain or gain power. For example, a department changing software will find staff pressuring managers for the product with which they have expertise. |

| Nonprogrammed Decisions | Recall that nonprogrammed decisions are novel decisions without the structure of previous decisions to guide them; this introduces uncertainty, which leads to political maneuvering. This also means programmed decisions are less political; that is, even if there are no policies in place, if a process is established and followed consistently, there is less likelihood of politics. | People or groups may try to steer decisions toward personal gain instead of optimization for the company. For example, a new office location is rare enough to be unprogrammed, and departments are likely to lead managers to assign them the most attractive spaces. |

| Organizational Change | Periods of organizational change, such as a restructuring or change in leadership, bring uncertainty and thus political behavior, as individuals and groups want to influence the change itself and benefit from it, or at least minimize the damage (if the change brings cutbacks, layoffs, etc.) | People or groups attempt to use this change as an opportunity to favor their own interests, such as trying to choose a leader who prioritizes their own department or steer reorganization toward giving them more power and autonomy. |

Because most organizations have at least one of these—scarce resources, ambiguous goals, complex technologies, and sophisticated and unstable external environment—most organizations have some political behavior. As a result, contemporary managers must be sensitive to political processes.

We often describe office politics as individuals maneuvering for power, but organizational politics also involve intergroup relations. Following from the understanding that politics are more likely when there is uncertainty or limited resources, you can see intergroup politics manifest in two ways:

According to Pfeffer and Salancik’s resource dependence model, we can analyze intergroup political behavior by examining how critical resources are obtained, controlled, and shared. Their model specifically focuses on resources in the external environment. That is, when one group in an organization (perhaps the purchasing department) controls a resource obtained from the external environment (the power to decide what to buy and what not to buy), that department acquires power. As such, this department is in a better position to bargain for the critical resources it needs from its own or other organizations.

Groups can also attain power by gaining control over activities that are needed by others to complete their tasks. These critical activities have been called strategic contingencies. A contingency is the extent to which one group’s fate rests in the hands of another entity.

EXAMPLE

The business office of most universities represents a strategic contingency for the various colleges within the university because it has veto or approval power over financial expenditures of those colleges. Its approval of a request to spend money is far from certain.Thus, a contingency represents a source of uncertainty in the decision-making process. A contingency becomes strategic when it has the potential to alter the balance of interunit or interdepartmental power in such a way that interdependencies among the various units are changed.

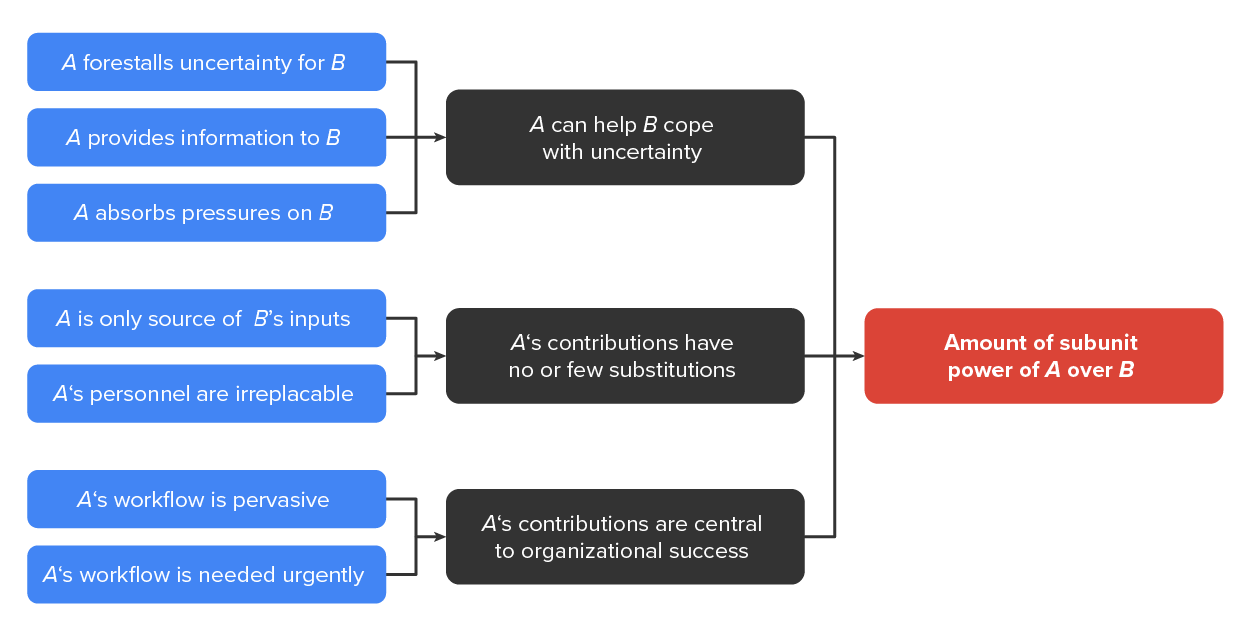

To better understand how the strategic contingencies that give one unit within an organization power over another, consider the model below. This diagram shows three factors that influence the ability of one department (called A) over another (called B). Basically, departmental power is measured by:

According to the strategic contingencies model of power, the primary source of department power is the unit’s ability to help other units cope with uncertainty. In other words, if our group can help your group reduce the uncertainties associated with your job, then our group has power over your group.

As shown above, there are different ways one department can ameliorate uncertainty for another. Below we will continue calling the department that has political power, A, and the department they influence, B.

Substitutability is the ease with which something can be replaced. This is determined by:

Centrality is how interconnected a department is to other departments within the organization. This is determined by:

Given that some departments have power over others, this can lead to an elite status, abuse of power, and dysfunction. How can organizations diffuse power for a more functional environment?

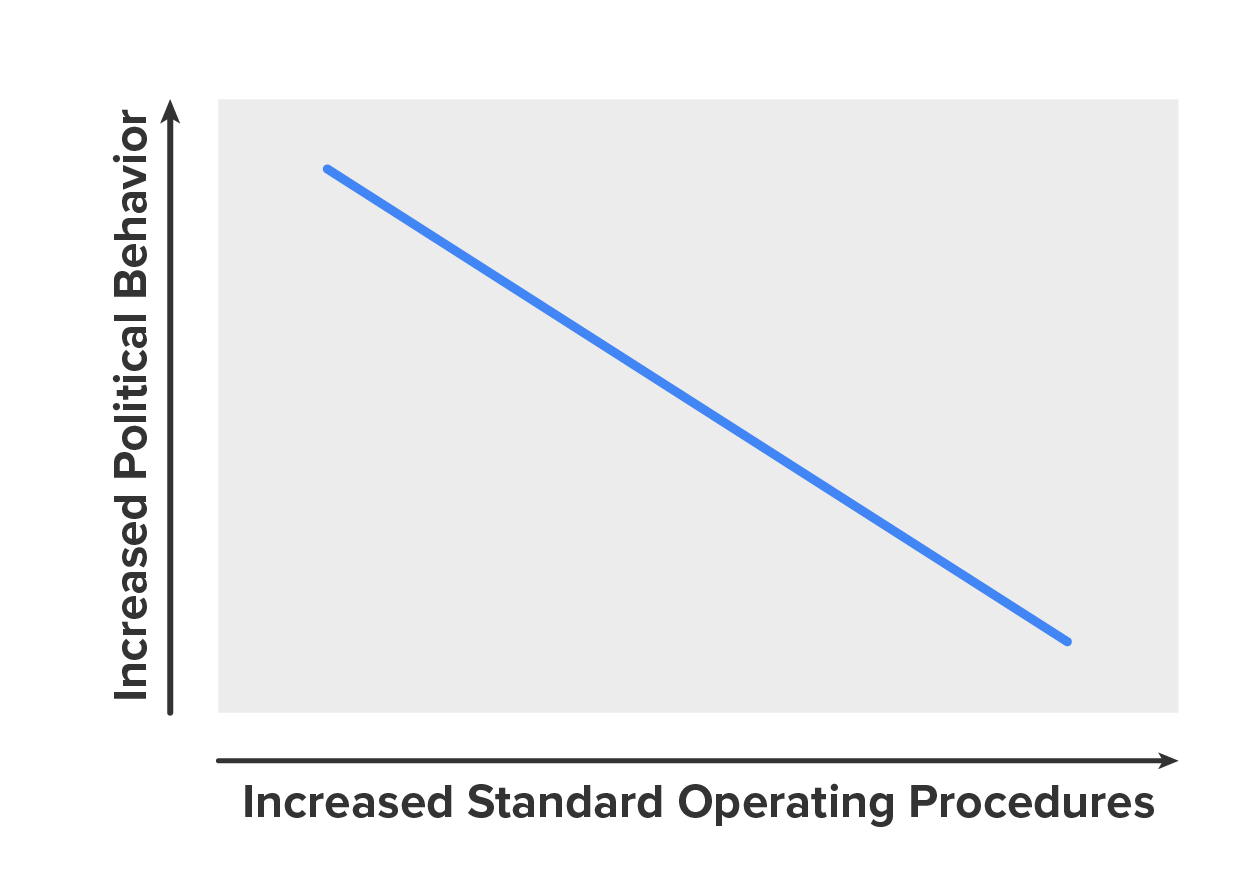

Policies are aimed at reducing the uncertainties that lead to political behavior. The effort to encourage more “rational” and predictable decisions in organizations was a primary reason for Max Weber’s development of the bureaucratic model. Research shows that as procedures and policies are better documented, political behavior decreases.

Managers can also reduce uncertainty by clarifying job responsibilities, benchmarks for evaluations and rewards, and so on. The less ambiguity in the system, the less room there is for dysfunctional political behavior. Managers can also reverse this script and use ambiguity to foster competition, to motivate employee actions, or to advance their personal goals.

Managers can reduce interpersonal or intergroup competition (and thus political behavior) by using impartial standards to allocate resources. They can also emphasize the goals of each department within the entire organization, the ends toward which all members of the organization should be working. This also helps reduce the perception of political behavior.

Fiefdoms get their name from (supposed) conditions in Medieval Europe where estates were relatively autonomous, and the landowner had authority over the peasants who lived there and worked for the landowner. In the organizational sense, the term is used to describe dysfunctional organizations where departmental managers compete for resources and control. High-level managers can attempt to break up existing political fiefdoms through personnel reassignment or transfer or by encouraging cooperation between departments. Managers can prevent future fiefdoms through fair and transparent methods for allocating resources and rewards, selecting and promoting staff, etc.

To the extent that employees see the organization as a fair place to work and to the extent that clear goals and resource allocation procedures are present, office politics should subside, though not disappear. In organizations where politics prosper, in fact, you are likely to find a reward system that encourages and promotes such manipulative, results-oriented behavior. The choice is up to the organization, and allowing managers to wield power unchecked, without regulation, is by its very absence a choice. The inaction of the organization becomes implicit approval, and divisions and conflict are often symptoms of a larger organizational dysfunction.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR". ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ORGANIZATIONAL-BEHAVIOR/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.